Plagiarism: An Open Letter to the Genealogical Society of Ireland

Plagiarism is the copying or paraphrasing of other people’s work or ideas without full acknowledgement. - University of Oxford

The webpage of the Guild of One-Name Studies relating to its April 2013 Conference and AGM in England features the following notice:

'Origins and Meanings of Irish Surnames, John Hamrock, This talk has been removed from the Guild website for copyright reasons' (http://www.one-name.org/talks/conf2013.html).

Why would it be found necessary to post

such a

notice? As

the case very much involves the Genealogical Society of Ireland, as

that body has declared that 'no further

correspondence whatsoever will be entertained on this matter' and

because a false narrative is in circulation, it has

been decided to proceed by way of an open letter. The writer

understands that a former Genealogical Society of Ireland Chairman

was or is his

society's representative for the Guild of One-Name Studies in Ireland.

John Hamrock has recently been appointed Chairman of the Genealogical

Society of Ireland, promising that a 'key focus will be on Education

and Training' and to 'look to offer distance learning possibly in

partnership with leading third level institutions' (Ireland's Genealogical Gazette,

May 2014, page 1).

By way of background,

I noticed in May 2013 that slides/handouts containing drafts of my work

in progress on Irish surnames, entrusted

to students in class, had been reused without permission by Mr Hamrock

as a core part of his presentation to the Guild of One-Name Studies

at the aforementioned conference in April 2013, being then published

online.

Having tried and failed to negotiate a

resolution with Mr Hamrock, I entered a complaint with the US-based

Association of Professional Genealogists of which he was a member. On

1 October 2013 this association

decided that Mr Hamrock was in violation of its code of ethics in that

he copied the

information in eight slides of the present writer relating to Irish

surnames without giving adequate credit and in breach of the principle

of 'fair use'. Having considered the facts of the case, the Guild

of One-Name Studies properly removed the presentation from its

website as noted above, but Mr Hamrock made no move to apologise or

make amends.

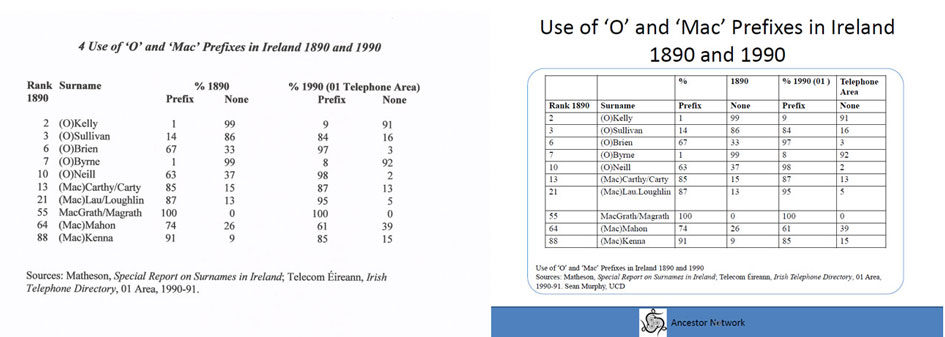

Most of

the tables in question were in fact out

of date, having been

amended and published in the writer's article 'A Survey of Irish

Surnames 1992-97'

(http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/studies/surnames.pdf),

and on

that account alone were not suitable for reuse. For example, as

illustrated below, Mr Hamrock copied an old class handout of mine

illustrating use of surname prefixes based on the Dublin area telephone

directory only, which I have since amended to include data from the

telephone directories for the whole of Ireland (see 'Survey of Irish

Surnames', pages 21-22). It seems obvious that it is highly unethical

for a student to reuse a teacher's material in this way, and as I

pointed out to Mr Hamrock in an unacknowledged e-mail dated 25 May

2013, 'where a scholar has produced clearly identifiable published

work, reproducing material from their old lecture notes without

permission and citing their name and educational institution only could

not be regarded as giving full and proper credit to their work'.

Example

of archived class slide/handout of Sean Murphy 2007 (left),

unauthorised copy used by John Hamrock 2013 (right),

which implies that he carried out research in the sources listed with perhaps some unspecified assistance from myself.

There are other examples of

plagiarism or presentation of the work of another as one's own with

which the other party is involved. A Genealogical Society of Ireland

course description at

http://familyhistory.ie/wp/courses/

contains the following words:

'Topics to be covered include the principles of genealogy, computers

and the internet, place names and surnames, location and use of census,

vital, valuation, church and other records. Practical advice will be

shared with participants as they embark on the quest to trace their

ancestors.' This is verbatim and near-verbatim copying of text from the

description of a long-standing introductory course given by the present

writer:

'Topics to be covered include principles of genealogy, computers and

the Internet, place names and surnames, location and use of census,

vital, valuation, church and other records. Practical advice and

guidance will be given to students embarking on the work of tracing

their ancestors.' Again, it simply is not acceptable for

someone to

set

up as an educator and re-use the class material of a former teacher

rather than carefully compile their own, and such action undermines and

devalues the course being copied. Unfortunately, it would appear

that unacknowledged copying has become habitual, in that an article

republished on Ancestor Network's site

contains the definition, 'Heraldry, to most people, is the practice of

designing, displaying, describing, and recording coats of arms and

heraldic badges', which is a slightly altered version of Wikipedia's definition,

'To most, though, heraldry is the practice of designing, displaying,

describing, and recording coats of arms and heraldic badges'.

It might be observed that the attitude of the Genealogical Society of Ireland

itself to the copying of material from its publications is anything but

casual, as demonstrated by the following prefatory warning in its Journal:

All rights reserved. No part of this Journal may be reproduced or utilised in any way or means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, filming, recording, video recording, photocopying or by any storage or retrieval system, or shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold or otherwise circulated in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published without the prior permission, in writing, from the publisher Genealogical Society of Ireland.

The

present writer has been in the habit of appending a shorter statement

to his publications, hopefully serving both to protect his intellectual

property from misuse and at the same time not to discourage others from

making reasonable

use of same: 'Contents may be freely reproduced offline for fair

personal and educational use, with proper acknowledgment' (this text

may need to be revised in the light of lessons learned in the present

ongoing case). It might be noted here that the US

concept of 'fair use' is a good one, being defined as 'a legal doctrine

that portions of copyrighted materials may be used without permission

of the copyright owner provided the use is fair and reasonable, does

not substantially impair the value of the materials, and does not

curtail the profits reasonably expected by the owner' (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fair%20use).

I

have no objection, indeed I am very happy to see published articles of

mine being

used by others, provided that it is done appropriately and with proper

credit, and that might include a table or two in a lecture presentation

properly referenced as to source. However, it is clearly not acceptable

to use eight tables from a teacher's old class handouts and present

them as though they were based primarily on one's own research.

Having devoted thousands of hours work to

the subject, I am willing and able to deliver lectures on Irish

surnames in my own right and can hardly be expected to acquiesce in someone else presenting my research as his work

at conferences. Efforts to resolve the dispute by negotiation

before proceeding by way of

formal complaint proved fruitless and at the moment of writing there

has been no admission of wrongdoing, no apology and no effort to make

amends (an attempt has been made to pressurise me to remain silent).

While the case was taken very seriously in the USA and England as

indicated, the

writer understands that the matter has been represented in Ireland as

in effect a 'petty,

personal dispute', with the personal pettiness allegedly lying on the

present writer's side, but it is or should be clear that plagiarism is

a very

serious matter impacting adversely on standards in Irish genealogy.

Unfortunately, the matter of plagiarism does not end with the examples cited above, as

there are even more serious instances of unacknowledged verbatim

transcription, as detailed in the

following sample parallel texts relating to an article in a publication

produced by

the Genealogical Society of Ireland, Essays Presented to Liam Mac

Alasdair, FGSI (accessible online

and to which volume the present writer was also a contributor at a time

when he was endeavouring to work constructively with the Society).

| In 1021 MacConcannon, lord of Hy Diarmada,

was killed by O'Gadhra. In 1023 O'Conor, King of Connaught, made an

expedition into Brefne, where he killed Donnell O'Hara, King of

Luighne. In 1024 occurred "the battle of Ath na Croisi in Corann,

between Ua Maeldoraidh, i.e. King of Cenel Conaill, and Ua Ruairc, when

O'Ruairc was defeated, and a terrible slaughter of the men of Brefne

and Connacht was committed by the Cenel Conaill" (L.C., A.U., F.M.,

A.T.). The O'Haras and O'Garas seem to have been opposed to O'Conor and

on the side of O'Ruairc in the years 1021 and 1023, and to have been on

his side, together with O'Ruairc, in 1024, combining to resist the

Ulstermen. But this reading depends on the description of those who

were killed as "of Brefne and Connacht." So it may have only beeen a

successful raid against O'Rourk and his allies, who could not resist

Ulster without help from O'Conor. All accounts call it a defeat of

O'Rourk, who is said to have lost 2000 men. [A footnote 20 refers to

Knox as in right column but uses 2000 reprint.] John Hamrock, ‘The origins and chief locations of the O Gara Sept’, Rory J Stanley, Editor, Essays Presented to Liam Mac Alasdair, FGSI, Genealogical Society of Ireland, Dun Laoghaire 2009, page 55. About this period (AD 1135) the kingdom of Luighne seems to have been practically broken into two separate kingdoms under O'Gara and O'Hara, the former holding as his kingdom so much as in the county of Mayo, with the country of the Gregry under him. The O'Haras may be held to be no longer Mayo men, having no supremacy over Gailenga. [A footnote 23 refers to Knox as in right column but uses 2000 reprint.] Hamrock, 'O Gara Sept', page 55. An Augustinian friary was said to have been established by O Gara in 1423 in Knockmore, Co. Mayo, of which the doorways and windows are in good preservation; and it is still a favourite burial place. [A footnote 30 refers to O'Hart as in right column.] Hamrock, 'O Gara Sept', page 56. The MacDermotts retained their rank as lords of Moylurg down to the end of the 16th century; and as successors to the O'Garas continued to hold considerable property at Coolavin, in Co. Sligo, down to recent times; and The MacDermott is still known as Prince of Coolavin. [A footnote 40 refers to Woulfe as in right column.] Hamrock, 'O Gara Sept', page 58. The establishment of the Gaileanga in Connaught probably took place for the same reasons and at the same time as the settlement of the Luighne there. By the official genealogies they are shown to be descended from Cormac Gaileng (whose name may have been invented for the purpose) through Art Corb who was a son of Laoi, the eponymous ancestor of the Luighne. Towards the end of the tenth century Gallen came under the power of the chieftains of Luighne, chiefly the Í Gadhra, who ruled it till the early thirteenth century when it (sic) was pushed aside by the Jordans. This area was afterwards called Mac Jordan's country. [A footnote 12 refers to McKenna as in right column, but uses 1980 reprint.] Hamrock, 'O Gara Sept', page 53. Little is known of the ancient rulers of Sliabh Lugha, but the area's name probably derives from Lug Lámfata (in modern Irish, Lugh Lámhfhada) 'Lugh the Longarmed', the most famous of the Celtic gods. The Luigne were closely related to the people called the Gailenga; these latter have given name to the barony of Gallen, Co. Mayo, which borders Sliabh Lugha on the west. The same two peoples were also settled close to one another in ancient Meath where they gave the name to the baronies of Lune and Morgalion/Machaire Gaileang. [Footnotes 6 and 7 refer to McDonnell-Garvey in right column.] Hamrock, 'O Gara Sept', page 52. In 1688 ninety per cent of the land in the county [Sligo] was owned by Protestants, making it the most Protestant part of Connacht. There were then about eighty-five landlords in the county. Half of them owned land there before the 1641 rebellion and Cromwellian war. A few like Taaffe, and Richard Coote, Lord Collooney, held estates of over 10,000 acres. Others, like Kean O'Hara, held over 4,000 acres. The O'Haras of Annaghmore were the only Gaelic landowners to survive. They had converted to Protestantism early in the seventeenth century. The Taaffes of Ballymote were the only substantial Catholic landlords to survive. Others, like O'Connor Sligo and the O'Garas of Moygara, were irrevocably dispossessed and disappeared from the history of the region. Some Gaelic families stayed on as tenants on their former possessions and re-emerged again during the Jacobite War. [A footnote 41 refers to Swords as in right column.] Hamrock, ‘O Gara Sept’, page 58. [No quotation marks or other indications are given that the above text has been transcribed verbatim or near-verbatim from the sources in the right column.] |

In 1021 MacConcannon, lord of Hy Diarmada,

was killed by O'Gadhra. In 1023 O'Conor, King of Connaught, made an

expedition into Brefne, where he killed Donnell O'Hara, King of

Luighne. In 1024 occurred "the battle of Ath na Croisi in Corann,

between Ua Maeldoraidh, i.e. King of Cenel Conaill, and Ua Ruairc, when

O'Ruairc was defeated, and a terrible slaughter of the men of Brefne

and Connacht was committed by the Cenel Conaill" (L.C., A.U., F.M.,

A.T.). The O'Haras and O'Garas seem to have been opposed to O'Conor and

on the side of O'Ruairc in the years 1021 and 1023, and to have been on

his side, together with O'Ruairc, in 1024, combining to resist the

Ulstermen. But this reading depends on the description of those who

were killed as "of Brefne and Connacht." So it may have been only a

successful raid against O'Rourk and his allies, who could not resist

Ulster without help from O'Conor. All accounts call it a defeat of

O'Rourk, who is said to have lost 2000 men. Hubert T Knox, The History of the County Mayo, Dublin 1908, pages 41-42. About this period the kingdom of Luighne seems to have been practically broken into two separate kingdoms under O'Gara and O'Hara, the former holding as his kingdom so much as in the county of Mayo, with the country of the Gregry under him. The O'Haras may be held to be no longer Mayo men, having no supremacy over Gailenga. Knox, History of County Mayo, Dublin 1908, page 45. A friary was erected at Knockmore, in the 14th century, by O'Gara, of which the doorways and windows are in good preservation; and it is still a favourite burial place. John O'Hart, Irish Pedigrees, or the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation, 1, 5th Edition, Dublin 1892, page 206. The MacDermotts . . . retained their rank as lords of Moylurg down to the end of the 16th century; and as successors to the O'Garas continued to hold considerable property at Coolavin, in Co. Sligo, down to recent times; and the MacDermott is still known as Prince of Coolavin Patrick Woulfe, Sloinnte Gaedhal is Gall: Irish Names and Surnames, Dublin 1923, page 350. The establishment of these Gaileanga in Connaught probably took place for the same reasons and at the same time as the settlement of the Luighne there. By the official genealogies they are shown . . . to be descended from Cormac Gaileng (whose name was probably invented for the purpose) through Art Corb who was a son of Laoi, the eponymous ancestor of the Luighne. . . . . . towards the end of the tenth century it [Gallen] came under the power of the chieftains of Luighne, chiefly the Í Ghadhra, who ruled it till the early thirteenth century when they were thrust aside by the Jordans; it is often afterwards referred to as Mac Jordan's country. Lambert McKenna, Editor, The Book of O'Hara: Leabhar Í Eadhra, Dublin 1951, pages xviii-xix. Little is known of the ancient rulers of Sliabh Lugha, but the area's name name may give us a clue . . . . . the most famous of the Celtic Gods . . . Lug Lámfata (in modern Irish, Lugh Lámhfhada - 'Lugh the Longarmed') . . . . . the Luigne were closely related to a people called the Gailenga; these latter have given name to the barony of Gallen Co. Mayo, which borders Sliabh Lugha on the west. The same two peoples were also settled close to one another in ancient Meath where they gave name to the baronies of Lune and Morgalion/Machaire Gaileang. Máire McDonnell-Garvey, Mid-Connacht: The Ancient Territory of Sliabh Lugha, Manorhamilton, Co Leitrim, 1995, page 9. In 1688 ninety per cent of the land in the county was owned by Protestants, making it the most Protestant part of Connacht. There were then about eighty-five landlords in the county. Half of them owned land there before the 1641 rebellion and Cromwellian war. A few like Taaffe, and Richard Coote, Lord Collooney, held estates of over 10,000 acres. Others, like Kean O'Hara, held over 4,000 acres. The O'Haras of Annaghmore were the only Gaelic landowners to survive. They had converted to Protestantism early in the seventeenth century. The Taaffes in Ballymote were the only substantial Catholic landlords to survive. Others, like O'Connor Sligo and the O'Garas of Moygara, were irrevocably dispossessed and disappeared from the history of the region. Some Gaelic families stayed on as tenants on their former possessions and re-emerged again during the Jacobite War. Liam Swords, A Hidden Church: The Diocese of Achonry 1698-1818, Blackrock, County Dublin, 1997, pages 18-19. |

As can be seen, the text on the left is

copied

mostly verbatim and sometimes near-verbatim from the

authors listed on the right, with no use of inverted commas or other

indications of

quotation. In contrast, the first two pages of the article are composed

mainly of three large blocks of indented quotations from correctly

cited authors (Hamrock, 'O Gara Sept', pages 50-51), but the

continuation of this style throughout the whole piece would have been a

frank admission that it was substantially copied, indeed to a somewhat

absurd degree. Although the

sources exploited in the case of the unmarked quotations are listed in

footnotes, the impression given

is that

the text is the original composition of the author rather than the

words

of others. In the first quotation in the table above, the letters

'L.C., A.U., F.M., A.T.' are Knox's abbreviations for the Annals of

Loch Cé, Annals of Ulster, Annals of the Four Masters and Annals of

Tigernach respectively, and the verbatim copying of another's author's

source citations is of course another form of plagiarism.

It has been suggested to me that the

failure to

indicate quotation is

an insignificant oversight and that while the standards of sources use

and citation I

advocate are appropriate for a university, they should not apply to

amateur publications.Of course amateurs are not exempt from having to

adhere to basic standards, and I would certainly not defame

non-professional genealogical authors by accepting that many or most of

them would regularly engage in unacknowledged verbatim copying of the

work of other authors. Mr Hamrock, who is a professional

genealogist, actually provides evidence that he knows well how to treat

the work of another author appropriately, in that in the article cited

above he had occasion to quote from one of my publications in

perfectly correct form using quotation marks:

This is a very important point not

always understood

by those who have not received training in scholarly composition,

namely, that avoidance of plagiarism requires not only citation of

sources used but clear distinction between original and quoted text.

The University of Oxford, for example, having defined plagiarism as

'the copying or paraphrasing of other people’s work or ideas without

full acknowledgement', goes on to make it clear that avoidance of

plagiarism entails clear identification of quoted material:

Harvard too is quite explicit on the need to mark quotations clearly:

Verbatim

plagiarism

If

you copy language word for word from another source and use that

language in your paper, you are plagiarizing verbatim. Even if you

write down your own ideas in your own words and place them around text

that you've drawn directly from a source, you must give credit to the

author of the source material, either by placing the source material in

quotation marks and providing a clear citation, or by paraphrasing the

source material and providing a clear citation. (http://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k70847&pageid=icb.page342054)

It

could not be said that an author who intersperses their own composed

text with substantial unmarked verbatim transcriptions of the work of

others is doing anything other than using that work without full and

proper acknowledgement and in effect passing it off as their own.

Typically a block of plain scholarly text referenced to the work of

another author indicates that it is original composition which is

paraphrasing, drawing on or significantly influenced by that person's

work, but where direct quotation occurs it is imperative that it is

indicated clearly, usually by quotation marks or indentation as stated.

While deliberate plagiarism is

notoriously difficult

to prove legally, Alex Haley's Roots,

still admired and advanced as a research model by unaware genealogists,

furnishes an open and shut case, in that Haley was found to have copied

passages from Harold Courlander's The African and was obliged to pay substantial damages (New York, 12 February 1979, page 69, accessed via books.google.com).

Many accused plagiarists seek refuge first in denial, often followed by

a claim that any copying was inadvertent, but lack of intent is

actually no defence to a well supported charge of

plagiarism, which in any case usually

results from a combination of want of care and inadequate

scrupulousness. In my experience most of

those shown to have copied verbatim without proper acknowledgment are

apologetic and seek to correct their mistake. I would certainly not

be found wanting if even at this late state there was an acceptable

apology and offer to make amends in relation to the inappropriate use

of my class material as described above.

How does one write without

plagiarising? A dedicated scholar will typically study many sources and

balance them one against the other before synthesising new text, often

interspersed with a reasonable quantity of quotations from other

authors clearly marked in inverted commas, or in the case of longer

quotations, indented. All relevant sources must be cited, usually by

footnotes or endnotes, and in the case of a longer study a concluding

sources list is also necessary. No student leaves my classes

without being taught that plagiarism is wrong and given practical

guidance on how to compose scholarly and properly referenced text, and

I am concerned that if I remain silent the standards exhibited

in

the above work will be

seen to

be a product of my teaching. As online and distance genealogical

education expands

it would be most unfortunate if it became commonplace or acceptable for

course providers to make inappropriate use of the work of others.

Furthermore, at a time when genealogical speaking spots and

professional lecturing opportunities are much sought after, it is

entirely unfair that any individual should be allowed to promote

themselves on the basis of the work of others, and organisers of events

and courses should endeavour to guard against such behaviour.

Given all that has been outlined above, it might

have been considered that there would be no further inappropriate use

of the present writer's material, but there is evidence that this was

occurring as recently as a month before the first version of this open

letter. Consider the following parallel extracts, respectively from the

present writer's treatment of surnames in his Primer in Irish Genealogy, 2013 edition (http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/epubs/primer.pdf),

and from John Hamrock's slide presentation to a 'Genealogy Conference'

at the Davenport Hotel, Dublin, on 9 May 2014 ( published online at http://www.irishgathering.ie/images/AncestorNetworkSonsoftheAmericanRevolutionGenealogyConference.pdf).

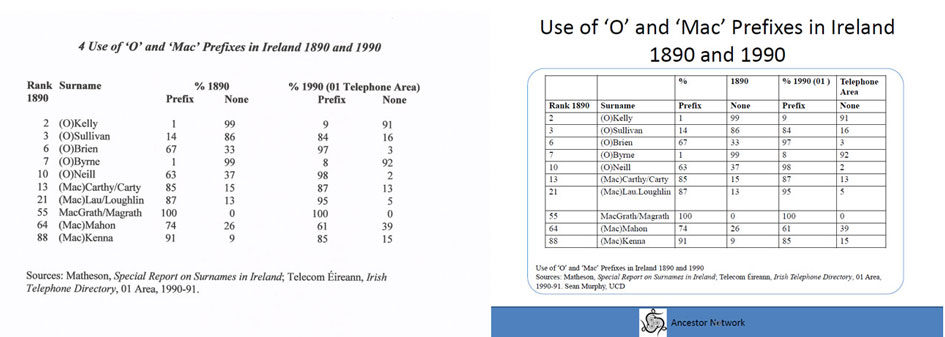

Screen print from Sean Murphy's Primer in Irish Genealogy, 2013 edition (left), slide displayed by John Hamrock

at a conference on 9 May 2014 (right), containing unacknowledged verbatim copying from the former.

It can be seen that phrases and definitions have

been copied from my work without use of quotation marks or

acknowledgement, eg, 'Monogenetic surnames have a single origin from

one individual [or] family', 'Polygenetic surnames arose independently

in different places and at different times, examples being Murphy or

Smith', 'Descriptive names referring to an individual's person or

appearance', while 'Placenames or toponymics derived from placenames'

is merely garbled. Some changes have been made, such as substituting

'Feerick

or Hamrock' for 'Faherty or Asquith', and some additional information

has been added, but in general it is clear that Mr Hamrock has again

been engaging in unacknowledged verbatim copying. The slides are

branded with the name of the firm, 'Ancestor Network', and furthermore

the whole presentation is marked '© Ancestor Network 2014'. The slide

presentation of 9 May 2014 features a reading list but there is no

mention of my Primer in Irish Genealogy or any other of my works dealing with surnames, such as 'A Survey of Irish Surnames 1992-97' (http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/studies/surnames.pdf). I have included citations of sources in the above extract from my Primer

to emphasise the importance of always giving due credit to the work of

others, and like all my former students, Mr Hamrock received rigorous

scholarly training in citing sources and avoiding plagiarism. It is

clear at this stage that there is more than just accidental unawareness

of scholarly principles involved here. Furthermore, on a practical

level it would be imprudent of

me as a professional author to fail to

challenge the unacknowledged copying and republication of my work, lest

in time I myself should stand accused of plagiarism.

While all the matters outlined above should give rise to

concern and do nothing to counter the view that genealogy is not a

serious scholarly subject, it would not

be an exaggeration to say that the 'O Gara Sept' article in particular

constitutes one of the worst cases of plagiarism that the

present writer has ever

encountered.

One would imagine that as the plagiarism appears in one of

their publications, it ought to be a matter of grave concern to members

of the

Genealogical

Society of Ireland, but the only response to date has been a threat of

legal action. To be fair, it should also be recorded that a few

individuals have indicated to me that they do not regard as

unreasonable my actions in defence of my intellectual property and in

support of basic scholarly standards. Writing in an individual capacity

as usual, I

conclude by exhorting former students in

particular not to acquiesce in or emulate the kind of behaviour I have

outlined above, nor to allow themselves to be persuaded that the

scholarly ethics they have been taught are in some way superfluous or

'eccentric'.

Sean

J Murphy

17 June 2014, last

revised 19 July 2015