|

|

|

|

|

|

The Woodland League |

|

Local Placenames around Kiltullagh (Athenry), Co. Galway

The townland is the smallest administrative division in Ireland covering on average about 350 acres, although some can be several thousand acres while others are less than an acre in size. It is the most ancient geographical unit in Ireland, often named in pre-historic times. The townland name often reflects the name of some local physical feature (a mountain, bog, or forest), resident (King or Lord) or landmark (a village or a church) in the area (Flanagan and Flanagan 1994).

The townland became standardized as the unit of measurement during the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century surveys and thus the names were transferred from the oral tradition to the written tradition. The First Series Ordnance Survey (O.S.) map, published around 1840, contains the townland names, about 60,400 for the entire country, of which 4,672 are in Galway. During this process many local placenames were not recorded as townlands with the result that they remained in the oral tradition or were lost.

Unfortunately, the feature(s) after which the townlands were named are often now long gone, so the meaning of the townland name may be lost. Several extensive studies have been undertaken to try to interpret the meaning of townland names (Joyce 1869; Flanagan and Flanagan 1994; Ulster Placename Society). There is general agreement that a name with 'Kil' refers to a church, although it could also be 'coill' (a forest), anything relating to 'gainnimh' relates to 'sand' while 'rath', 'lis', 'lios' and 'caher' refer to forts, with the name of the fort owner sometimes following. For example, Rathcormac would be 'Cormac's rath.'

In addition to townland names, there is also a host of local placenames in every parish. These include field names, names of mounds, forts, bridges etc. and placenames not included in the First Series O.S. map. Some of these can be found on very old maps (such as the 1817 Larkin Map of Galway, or estate maps), others have been retained in the oral tradition, while others have been lost over the years. Many placenames not written have been retained in the oral tradition for hundreds, or even thousands, of years. These placenames may only be known to a few people in the locality and if not recorded may be lost. They can often have a very important meaning for the locality, reflecting a past that is no longer apparent.

This article is an attempt to record some local placenames within about two miles of the village of Kiltullagh, 6 miles east of Athenry, Co. Galway. It identifies the places referred to so that they can be located precisely and their origin traced by future generations, even if the name is no longer used

The boundaries of some of the places are indistinct and may even vary, depending on whom you ask. The grid reference refers to the centre of the place referred to, unless it is a very specific place like a bridge.

Placenames from 1817 map

Section (south-east of Kiltullagh village) of Larkin's 1817 map of Galway showing Carheny, Glanamiltogue, Balinfish and Coachgop.

In 1817, Larkin produced a map of Galway showing the principle placenames in the county in addition to other features like roads etc. In the area around Kiltullagh, many of the placenames have been later recorded as townlands, while others have been preserved in the oral tradition. Others have been lost from both the written and oral record.

Glanamiltogue 598 238: Towards the east of the townland of Carrowkeel, on the border with Knocknadala just to the east of the disused railway line (soon to become a road) there are a few fields known locally as Glann. On the 1840 O.S. map there are a few houses in the area, which are shown as being in Carrowkeel. Few traces of these houses remain today. On the 1817 map and an 1833 Estate Map of Raford Estate this area is shown under the name Glanamiltogue. The name Glanamiltogue was not recognized as a townland, but the name has carried on in the oral tradition for almost 200 years, albeit in an abbreviated form of Glann. Presumably, Glannanulty in 1821 census is synonymous with this area

Ballinfish 539 232: South of Glanamiltogue is an area called Ballinfish on the 1817 map. There is no recollection of this placename in the locality.

Carheeny 592 242: Also on the 1817 map there is an area called Carheeny. This would equate to a section of the townland of Carrowkeel, this time towards the north. Although Carheeny doesn't exist as a placename, an area in that vicinity is known locally as Cotni (see later). Outside the immediate vicinity of Cotni the placename is pronounced as Coheny, which may be closer to the placename on the 1817 map.

Coachgop 585 235: The 1817 map shows the placename of Coachgop in the area where Bookeen is now. There is no recollection of this placename in the locality.

Placenames from 1821 census

The 1821 census for part of the parish of Kiltullagh survived the Four Courts fire of 1922 and has been published recently. Several placenames (like Poulatullane, Curraghdean, Cregville and Killeen) are listed in that census record but are not listed in later records like the Tithe Applotment Books or Griffith's Valuation. There is little additional information available about these placenames, except that Poletulla is given on Petty's map from the 17th century. Others placenames, such as Rathnafulachty and Lisnaherrick are listed alongside the current townlands of Raford and Knockatogher, respectively. Lisnacapple is listed in 1821 whereas Liscraple is given in Tithe Applotment Books of about 1825. Presumably, this is the same place, but its name was not included as a townland. Finally, Glannanulty appears to be synonymous with the area of Glanamiltogue from the 1817 map.

Placenames from the 1833 Raford Estate map

An estate map from Raford House (a branch of the Daly Family lived here) was discovered recently in the attic of a house in the townland of Raford. This map was restored and is now in a private collection. The map shows the lands owned by the estate, the occupier of the land and the name of the area where the land is situated. Many of the placenames still exist in the townlands of the area, but a few are not recorded as townlands. These placenames are still retained in the oral tradition of the area and are still used by the landowners.

Camp Park 614 230: On the Raford Estate map, the area immediately north of Turoe is called Camp Park. This name probably has its origin in the 17th century, when it is said that the Jacobite Army camped here on retreat from the Battle of Aughrim. A road leading through this area is called Sarsfield's road. Although now a cul-de-sac, it once continued through Galboley. It is said locally that before being called Sarsfield's road it was called Sli Coolan. The townland for the area shown as Camp Park is now Fearta. This has significance in itself, as fert is the old Irish word for 'grave' (Flanagan and Flanagan 1994). This is possibly the origin of the townland name as there were several burial mounds in this area (Jordan and O'Connor 2003). Several placenames, such as Cruchain Sile, Cruach Conari, Cruchain Coolan and Cruchain Art, are associated with these burial mounds.

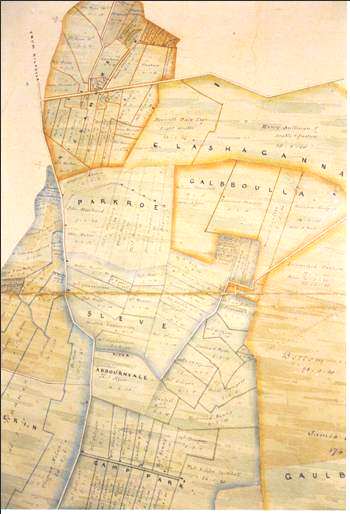

Section of the 1833 Estate map showing Reaskmore, Parkroe, Sleve and Camp Park Sleve (Sileveen) 608 236: Sleve is in the south part of what is now the townland of Knocknadala. It is a placename only now used by a few people whose ancestors lived in that area. Not having been transferred to a townland name, it has survived in the oral tradition for over 150 years. This is an unusual name as Flanagan and Flanagan (1994) say that 'sleve' does not appear as a name without a qualifying element.

Parkroe 602 240: This placename is synonymous with the north/west part of what is now the townland of Knocknadala. There is no oral record of the placename in the locality.

Thalla Park 622 240: The area on the 1833 map called Thalla Park is to the north-east of what is now Turoe, part of what is now Galboley townland. Although no longer recorded on maps, an area called Thaillye still exists in the oral tradition. The fact that this placename was used on birth certificates as late as the 1870's undoubtedly contributed to its retention as a placename. Within this area there is a square enclosure with a souterrain that is known locally as Rath Eoghain Tailleach, a legendary King of Munster in the early centuries of the Christian era.

Reaskmore 605 247: Reaskmore is a placename that features on both the 1817 and 1833 maps. This area is in the present townland of Clashaganny, although its location within the townland differs on the two maps. The 1817 map places it on the east side towards Carrowreagh, while the 1833 map places it on the west side bordering Carrowkeel and Killarrive. This placename is remembered in the oral tradition of the locality, although it is no longer in the written record.

Ballinascreagh 597 261: South of the present townland of Gortakareen, Ballinascreagh is listed on the 1833 map. It is listed as a placename in the Tithe Applotment records, but was not given the status of a townland.

Placenames with no written record

The following placenames are not recorded on any map, although some of them have been recorded in a recent book (O'Connor 2003) and others are widely used locally in the oral tradition.

Ballyknock 593 236: In the townland of Carrowkeel, half-way between Dunsandle Station and Bookeen church there is a group of houses down a boreen to the left. This area is called Ballyknock. There is no information locally as to the origin of this name.

Factory bridge 609 232: There is a river on the northern border of Fearta townland where it meets the southern border of Knocknadala townland. The road from Kiltullagh to Bullaun crosses this river at a place called Factory Bridge (shown as Ballykeeran bridge on the current Discovery Series maps). Despite exhaustive local enquiry, the origin of this name could not be found. However, on the 1840 O.S. map there is a disused hemp factory shown in the field beside the bridge. Although no trace of the factory exists, the placename Factory Bridge has remained.

Forge Hill 592 240: South-east of Dunsandle Station house, on the road from Kiltullagh to Bullaun, there is a hill just past the railway gates. This is known locally as Forge Hill. Although there is no physical trace or local knowledge of a forge on the hill, it is reasonable to assume that at some time in the past there was.

Cotni 592 242: This is the local name for a few fields in the north part of the townland of Carrowkeel (Carheny, see earlier). The area consists of about 40 acres that has been designated as a National Monument and entered in the Sites and Monuments Record. There it is recorded as a "Complex of earthworks in the townland of Carrowkeel, Parish of Kiltulla, Co. Galway, O.S. 6" Sheet 97." It consists of a series of interconnecting roads, rectangular house bases, ringforts, enclosures, a field system and souterain. It is all that remains of a much larger similar site. Hundreds of acres of similarly described land have been cleared over the years to provide stone for lime-kilns, filling for roads and to yield better land. This was an extensive urban-like population centre, which sprawled across Carrowkeel, Clogharevaun and Kiltulla.

The 'Dindsenchas' are a set of ancient documents that tell the legendary history of places in Ireland and were transcribed from the oral traditions of those places in the 10th/11th centuries. Significantly, no other part of the country has as many Dindsenchas records as Galway. Maen Magh is the ancient name of the plain surrounding Kiltullagh. Early Dindsenchas material referred to "the dense population" of this area: "O Maen na treibh tuillte co rein na fairrigi" (Dindsenchas of Maen Magh) meaning "from densely populated Maen Magh to the sea." Significantly, no other area of ancient Ireland was accredited with a dense population, as was Maen Magh. In MacNeill's 'St Patrick', one population centre said to have been visited by the Saint was Campus Cetni in South Connaught, a place never identified. Corroborating these astounding records, the area around Cotni was traditionally regarded as part of an ancient town or urban centre, a fact taught in the local National School at the beginning of the 20th century.

Pairc na hUanna 593 238: This is a phonetic spelling from the pronunciation of an elderly lady over 30 years ago. It is the name given to a field 200-300 metres south of Cotni. According to the elderly lady it was an old graveyard. Indeed, there is a ringfort shown in this area on the First Series Ordnance Survey map, but it was ploughed out over 100 years ago. Recently, part of this ringfort in Pairc na hUanna was excavated in preparation for construction of a new road between Galway and Balinasloe. Many skeletons were recovered and although dating has not yet been completed, the indications are that it was an ancient burial ground. Full publication of the excavation data by Galway County Council/NRA will follow in due course. From our point of view, it is interesting that the field name turned out to reflect a long past and almost forgotten graveyard of which no trace existed on the surface and which may be several hundred years old.

Sachell 580 244: In the east part of Cloghereavaun townland, just north of the river, there are a few fields called Sachell. This name only exists in the oral tradition and its origin is not known locally. Within these few fields there were many enclosures that have now been destroyed. Three of these were called Rath Shachell, Kell Shachell and Domhna Shachell, normally indicating the fort, church and cemetery of a bishop, respectively, whose name is added at the end. Interestingly, there was a pre-patrician bishop called Sachellus who preached in south Connaught. Similarly, there was another pre-patrician bishop called Hernicus who preached in south Connaught. There is a townland called Ratherneen and a placename called Domhnaherneen. O'Loughlin, who shows this on his map of Irish early Ecclesiastical sites, confirms that there was an early Christian site at Kiltullagh.

Gortnascoile 588 247: Gortnascoile (field of the school) is the name of a field in south of Killarrive townland. There is a relatively modern shed in the field, but no trace of any other structure. The field has been in the ownership of the Ward family of Killarrive for centuries, as the ancestors of the current owner can be traced through the 1821 census, the Tithe Applotment Books and Griffith Valuation records (Jordan 2000) and National School records for the local school. As the name implies, this was probably the site of a hedge school. Although there is no physical trace of this school, there is an oral tradition of a school in the vicinity of this field during the 19th century. There is also a tradition that a teacher in the National School in Kiltullagh, who lost his job as a result of his support for the Land League, set up a hedge school in the area. The name of the field is all that records the possible location of this hedge school.

The Rooans 598 242: In the townland of Raford there is a field known as The Rooans. This field had two earthen embankments approximately one metre high, 4 metres wide and 10 metres apart. One of these embankments has been leveled, while parts of the second have been trimmed in size, although the original width can still be determined. 'Roo' is an ancient Irish word for earthen embankment (O'Rahilly, 1946) and Rooans is a plural version of this. This implies that the origin of the placename goes back to at least when ancient Irish ceased to be used. There is no written record of the placename, suggesting that it has survived for many centuries in the oral tradition.

The Curraghs 588 254: In the north part of Killarrive, near the river, there is a field called the Curraghs. In this field there were two large earthen embankments that were leveled about 40 years ago. 'Curragh' is regarded as meaning 'swamp' (Flanagan and Flanagan 1994), although 'curragh' is also a name associated with a large earthen embankment in Clare (O'Rahilly 1946) and was an old Irish word for earthen embankment. 'Curraghs' is the plural of this and it is from these embankments that the field probably got its name. Therefore, this field name has remained in the oral tradition for centuries.

Cliadh Draighn 638 243: In the townland of Benmore there is a large earthen embankment. A poem written by a local man records this embankment that was called the Cliadh Draighn, a word used in the ancient Dindsenchas records for a dyke. Similar names for embankments are used around the country, for example, Cliadh Dubh and Cliad Rua in Munster. This name may, therefore, be very ancient and have existed in the oral tradition of the area for centuries.

Other placenames: There are several other local placenames that have been referred to in a previous article by Jordan and O'Connor (2003). These include ancient road sections called Escir Riada, Sli Dala and Rot na Ri (Road of the Kings) and a hill called Loovroe (O'Connor, 2003)

Concluding remarks: Even at the time when the Psalms were written in the centuries before Christ, people realized the importance of keeping the oral tradition alive:

'the things our fathers have told us we will not hide from their children but will tell them to the next generation. They too should arise and tell their sons.' Psalm 77.

Because of the movement of people and other changes in society, the oral traditions around Kiltullagh (and indeed around Ireland) are in danger of being lost unless a concerted effort is made to retain them. In a short distance of less than one mile, the preferred route of the N6 motorway from Galway to Balinasloe passes through six of the areas listed above where the placename is not recorded (Sachell, Cotni, Glanamiltogue, Parkroe, Reaskmore and Taillye). Putting signs on these areas to acknowledge their existence would be an ideal opportunity for Galway County Council/NRA to contribute to the continuity of these placenames and encourage a broader awareness of them.

References

1.Dindsenchas of Mean Magh.

2.Flanagan, D. and Flanagan, L. (1994), Irish Placenames. Gill and Macmillan.

3.Jordan, K. and O'Connor, T. (2003), Archaeological sites of interest surrounding the Turoe Stone. Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 55, pages 110-116.

4.Joyce, P. W. (1869), The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places.

5.McNeill, Eoin, (1964), Saint Patrick, John Ryan (ed). Clonmore and Reynolds, Dublin. Ulster Placename Society, see www.ulsterplacenames.org (accessed January 2005).

6.O'Connor, T. (2003), Turoe and Athenry: Ancient Capitals of Celtic Ireland. K. Jordan (ed). Tom O'Connor.

7.O Rahilly, T.F. (1946), Early Irish History and Mythology. Dublin.

|