|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

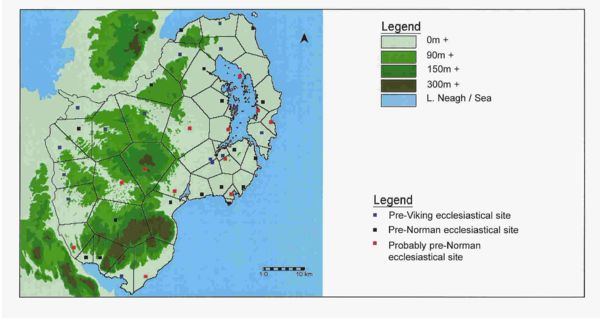

The patterns of settlement in Early Christian County Down

Thiessen polygon results based on the CORINE map

Results are shown as a percentage of the total area covered by each site type

Chi-squared values based on the Soil map

Individual values become significant at 3.8 Overall chi-squared vales become significant at 12.59

Chi-squared values based on the Land Classification map

Individual values become significant at 3.8 Overall chi-squared vales become significant at 19.68

Chi-squared values based on the CORINE map

Individual values become significant at 3.8 Overall chi-squared vales become significant at 16.92 The overall chi-squared values for raths on all three basemaps are below significant levels, indicating that raths have a wide distribution with their territories incorporating all categories of soil and land. It should be noted that raths are the only site type to which this applies, and it supports the Site Catchment Analysis results. For the probable raths the Thiessen polygon analysis results indicate that the territory is of a better quality than that of the known sites. Given the distribution of these sites, amongst the known raths, it seems likely that these are rath sites which have been damaged or removed precisely because they are located on the better quality land. The territories of the platform raths appear to be of fairly average quality, similar to that of the univallate rath, while the results for raised raths suggest that these sites are located in particularly good land. Overall, the territory of the mounds is of good quality and shares some similarities with both the platform and raised raths, but it remains impossible to be certain how many of these mounds are in fact Early Christian settlement sites. Considering the relatively large size of the Thiessen polygons of the raised raths, and the good quality of the land within them, these results again support the suggestion by Avery (1991, 125) and Mytum (1992, 126) that these are high status sites. Bivallate raths are also considered to be high status sites and this is reflected in the results of the Thiessen polygon analyses. From Tables 34 - 39 we can see that there are higher than expected quantities of the better quality categories; however, there are also higher than expected proportions of the rather more mediocre classifications, i.e. the type 19 (ABE/gley) soil and the B3 category on the Land Classification map, although this is compensated for by the significantly low values for the poorer categories. Overall, these bivallate raths are located with access to relatively large areas of the better quality, arable land. This confirms the results of the previous site catchment analyses, and clearly demonstrates that the territories of these bivallate raths are of better quality than that of the univallate raths. The results of the Thiessen polygon analyses for the multivallate raths indicate that the territories of these sites are similar to those of the bivallate raths, but not of quite as high a quality. These multivallate raths do not have the higher than expected quantities of the best quality A grade of land on the Land Classification map, or the agricultural category on the CORINE map that are found in the territories of the bivallate sites. As suggested in the previous chapter, this may mean that for the occupants of these sites a strategic position may have been more important than occupying the very best quality land. The same may be said of crannogs, whose territories appear to be of remarkably low quality, with a high proportion of Type 1 (PP/peat) soil, as well as the D category on the Land Classification map and the scrub classification from the CORINE map. The poor quality of the very large Thiessen polygons of these crannogs can at least partly be explained by the location of many of these sites in dried-up lakes, which have now turned to scrub or bog. However, this may support Warner’s assertion (1994, 61) that these were not the principle royal dwelling-site, but rather were strategic sites. For the large raths the results of the Thiessen polygon analysis shows that the quality of the land within the territory of these sites is low, mostly mediocre pasture land, and is certainly poorer than that surrounding the more usual sized raths. As suggested in the site catchment analysis discussion, the large size of these sites may be related to a predominance of pastoral farming. The large enclosures also have higher than expected proportions of pastoral land within their territories. Surprisingly the Land Classification map also indicates a high proportion of the best quality A grade of land within the area, but these large enclosures are also one of only a few site types which do not have significantly lower than expected values in the B4 and C1 categories. Again this reaffirms the site catchment analysis results, indicating that these sites are located on land mostly suitable for pasture. Raths pairs also appear to have been located on ground more suitable for pasture, again confirming the results of the site catchment analyses. This can be seen in the high values for the type 19 (ABE/gley) soil, the B3 and B4 categories on the Land Classification map and the good pasture classification on the CORINE map, resulting in significantly lower than expected values for those categories capable of sustaining arable farming. This may support that suggestion that the second enclosure of these pairs was for corralling cattle. A farmer who had enough cattle to justify building a second enclosure for them may not have needed to consider incorporating arable land into his territory. By contrast the two conjoined rath sites are both are located with a higher than expected proportion of good quality land within their territory, perhaps compensating for the small territory size. The Thiessen polygon results for those raths with souterrains indicate that these sites are located in rather middling areas, contrasting with previous analysis results which have indicated good quality ground. From the Soil map analysis we can see that while there are significantly high proportions of the good quality type 6 (ABE/SBP) soil within the Thiessen polygon areas, there are also high quantities of the rather poor type 15 (gley/ABE) soil. On the Land Classification map there are high quantities of the B3 category of land, which is of middling quality, but there are also significant proportions of the B4 category. The CORINE analysis confirms the rather poor nature of the Thiessen polygons of these raths with souterrains, with high proportions of the mixed pasture category. These results appear to contradict those of the site catchment analyses which, although somewhat contradictory themselves, overall appeared to demonstrate that those raths with souterrains were located on good quality land, better than those raths without. As some of these sites are located between the Mournes and Slieve Croob, it is likely that their Thiessen polygons incorporate at least some of the poor quality areas associated with the uplands. However, it remains difficult to reconcile these results and reach any firm conclusions on these sites. As with the site catchment analysis results, the Thiessen polygon results for isolated souterrains are very contradictory, with wide variations in the results from the three base maps. The Soil map results indicate higher than expected values for the best quality soil and low quantities of the poor quality. While the Land Classification map also has higher than expected proportions of the good quality A/B1 category, surprisingly the same applies to the much poorer C/B, C2 and B4 categories. The results from the CORINE map add to this confusion, with no particularly significant results. However, this is one of the few occasions when the value for the scrub category is not significantly lower than expected. Similarly confused results were obtained from the site catchment analysis. A possible explanation for this is that the occupants of the settlements presumably associated with these souterrains, were trading off the advantages of large areas of very good quality land, against the disadvantages of the poorer quality areas these settlement locations also entailed. It is clear from the Thiessen polygon results that cashels are located in particularly poor areas: they are one of only three site types with higher than expected levels of type 1 (PP/peat) soil. This is reflected in the B4, C and D categories on the Land Classification map and the scrub and forest categories on the CORINE map. There are also significantly lower than expected values for all the better quality categories on each basemap. When looking at these results, however, it is necessary to remember that the Thiessen polygons of these cashels incorporate the whole of the Mournes, because there are no other sites located within the mountain range. This also explains the large average size of the Thiessen polygons created by these sites. Overall, however, we must acknowledge that the territories of these cashels are of substantially poorer quality than those of raths, and again this raises the question of why an Early Christian farmer would settle in these areas. As with the Site Catchment Analysis results, the Thiessian polygons for the ecclesiastical sites produce some interesting results. The pre-Viking sites have higher than expected values for mediocre quality ground and on the CORINE map the only significant result is the very high proportion of the Thiessen polygon area which has now been built over. The territories of the Pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites are of much better quality than the pre-Viking sites. Here we can see higher than expected values for the best quality type 8 (ABE/BP) soil and A and B1 categories of Land Classification. As with the pre-Viking sites, the only significant result from the CORINE map is the high proportion now under artificial surfaces, i.e. urban areas, but overall we can see that these sites were located for access to as much arable land as possible. As with the site catchment analyses results, this confirms the growth in the power and wealth of the church during the Early Christian period. The results of the Thiessen polygon analyses for the probably pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites are rather surprising. On the Soil map there are higher than expected values for the type 19 (ABE/gley) soil, but also the very poor type 1 (PP/peat) category. Similar results can be seen on the Land Classification map, with low quantities of the B1 category and high for both the C1 and D categories. The CORINE results are equally poor, with a higher than expected value for the scrub category and, unlike both other ecclesiastical site types, an average value for the artificial surfaces category. These Thiessen polygon results for the probably pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites are very much poorer than those of the known pre-Norman sites. They also differ substantially from those of the site catchment analyses which suggested that these sites were located with access to good quality land. It may be that at least some of the sites in this category date to the pre-Viking period, and that this is distorting the results somewhat.

Thiessen polygons analysis based on only the ecclesiastical sites It was thought that it might be interesting to create Thiessen polygons using only the Early Christian ecclesiastical sites and these can be seen in Figure 24. The average size of the Thiessen polygons of each site type can be seen in Table 40 below.

Figure 24 Thiessen polygons of the ecclesiastical sites

Average size of Thiessen polygons of ecclesiastical sites only

The influence of these ecclesiastical sites would have extended far beyond the physical boundaries of the ecclesiastical enclosure itself, or the extent of the churches’ land holding. People from surrounding areas must have looked to these sites for their religious needs, but they also functioned as major economic centres, and it seems likely that most people would have visited the ecclesiastical sites at least occasionally for a variety of reasons.

Conclusions of the Thiessen polygon analysis The Thiessen polygon analyses demonstrate that the territories of the majority of site types are of fairly average quality land, suitable for the pastoral farming which dominated the Early Christian economy. Again we can see, however, that both raised and bivallate raths are located on particularly good ground, of better quality than that of both the univallate and multivallate sites. The territory surrounding the cashels remains particularly poor, and that surrounding crannogs is again also of a poorer than average quality. The Thiessen polygon results for both the pre-Viking and pre-Norman sites also conform to those of the site catchment analyses, and again appear to reflect the rise of the power and wealth of the church during the Early Christian period. Overall, the Thiessen polygon analyses results confirm those of the site catchment analyses in the previous section.

Final Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that there are certain clear trends and preferences in settlement patterns in Early Christian County Down. The majority of settlement is concentrated towards the west of the county, with few sites occurring on the Ards peninsula and to the north-east. Both bivallate and multivallate raths share this distribution pattern with univallate raths, although a cluster of raised raths and, surprisingly, souterrains, can be found in the Lecale area, in the east of the county. This is an area which is dominated by ecclesiastical sites and appears to have been avoided by raths. Isolated souterrains are located in a band running east – west across the southern area of the county, surprisingly continuing through the area between the Mournes and Slieve Croob. As expected, cashels are concentrated in these upland areas. The remaining site types, such as the crannogs or conjoined raths, are interspersed with the raths, with a wide distribution across the county. The exception to this is the ecclesiastical sites, which tend to be found on the periphery of the county, particularly around the eastern, coastal areas, which are less densely settled by raths. The reasons why the west of County Down is more densely settled than the eastern areas remain unclear and it seems somewhat surprising that so few settlements are located to take advantage of the resources of the sea and Strangford Lough. Overall the majority of settlement occurs in the 60m – 90m and particularly the 90m - 150m zones, ideal for both growing crops and raising cattle. Raths deliberately avoided both the low-lying areas, under 30m and the uplands, above 150m. Most other site types also demonstrated a statistically significant preference for these altitude zones. The exception to this is raised raths, which are the only secular site type with a strong preference for the lower, 30m – 60m zone, raising questions as to whether the heightening of these sites was a status symbol, or simply a desire to improve visibility and avoid water-logging in these lower-lying areas. Ecclesiastical sites also tend to be concentrated at lower altitudes than secular settlement sites, and particularly around the coastal areas avoided by the majority of raths. This indicates that rather than being in the centre of communities, and despite their economic role, the ecclesiastical sites were set somewhat aside from the secular settlements. Early Christian settlement in County Down is found right across the spectrum of land quality, although, with a few exceptions, the very poorest quality areas are clearly avoided. While there are versatile and fertile acid brown earth / brown podzolic soils in County Down, the majority of settlement is somewhat surprisingly found on the rather mediocre acid brown earth / gley areas. These soils are concentrated in the drumlin belt and most site types, including raths and multivallate raths, show a statistically significant preference for these soils. Only cashels and isolated souterrains indicate an avoidance of these soils, and a preference for the acid brown earth / brown podzolic soils, a preference shared by raised raths and conjoined raths. The location of raised raths in these better quality areas may support the suggestion that these are high status sites. Particularly notable is the fact that, although considered to be high status sites, multivallate raths and crannogs are not located on top quality land, indicating that strategic factors came into play. It is the ecclesiastical sites, particularly of the pre-Norman period, which are located with access to some of the best quality, arable land available, perhaps emphasising the power and wealth of the church during the later part of the Early Christian period. It appears, however, that for the majority of Early Christian farmers the quality of their land was of less consequence than the desire to live on a drumlin. We must remember that during the Early Christian period the landscape would have been considerably more wooded than today and many of the inter-drumlin hollows would also have been much wetter, probably either bog or small lakes. In these circumstances the hilltop location would have been vital in affording the Early Christian farmer good, dry land as well as a view over the surrounding territory.

Overall then we can see that a number of distinct settlement patterns have emerged from the various analyses, but perhaps the most significant result of this study has been the demonstration that altitude rather than land quality was the leading factor influencing settlement in County Down during the Early Christian period. Further study, using GIS to look at the association of sites with townland boundaries, tribal boundaries, rivers etc. would greatly contribute to our understanding of other factors influencing Early Christian settlement.

Bibliography to accompany this article

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||