Irish

Historical Mysteries: Eamon de Valera's

Father Vivion Juan de Valera

Eamon de Valera (1882-1975)

Resumen en

español: El político irlandés Eamon de

Valera nació en Nueva York en 1882, siendo sus padres Vivion

Juan de Valera y Catherine Coll. Se dice que Vivion Juan era

español o cubano, pero a pesar de intensas investigaciones no se

ha encontrado ninguna evidencia que lo demuestre. Se cree que Vivion

Juan murió en Nuevo México hacia 1885 y en el siguiente

artículo se plantea la pregunta de si pudiera haber sido natural

de dicho estado.

In the years since the

death of the Irish statesman Eamon

de Valera,

and even during his

lifetime, there has been considerable mystery concerning his paternal

ancestry. It is known that de Valera was born in New York on 14 October

1882, the son of Vivion de Valera or Valero and Catherine or Kate

Coll. De Valera fought in the Irish War of Independence but

famously split with Michael Collins on the issue of the Treaty

compromise with the British in 1921. De Valera inspired extremes of

devotion and

loathing, and his political opponents spread stories to the effect that

he was illegitimate. (1) Starting with the basic documentation, it can

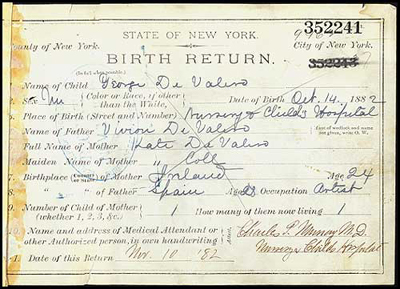

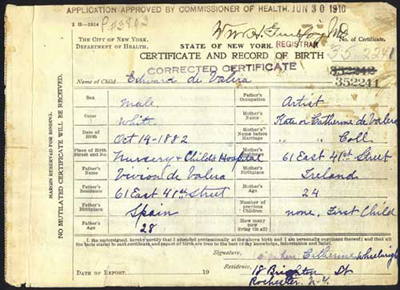

be seen that there are two

versions of de Valera's birth certificate, the first giving his name as

George

and his father's surname as de Valero, the second corrected version

issued in 1910 (not 1916 as has been claimed) at the request of his

mother, with the forename recorded as Edward (of which Eamon is the

Gaelic form) and

the family surname spelt de Valera. (2)

Both certificates indicate that Vivion was born in Spain about 1854,

and

that Catherine was born in Ireland about 1858. While Catherine's place

of origin, near Bruree, County Limerick, is well documented, persistent

efforts have so far failed to confirm Vivion's country of birth.

Original and corrected birth

certificates of Eamon de Valera

(images courtesy of New York City Department of Records)

De Valera's official biography

states that his father Vivion Juan (an added second name) was born in

Spain, that the latter's father Juan 'was engaged in the sugar

trade between Cuba and Spain and the United States', and that his

mother Amelia Acosta 'had died when he was young'. Vivion Juan and

Catherine Coll are said to have been married in Greenville, New Jersey,

on 19 September 1881. The official biography further states that Vivion

Juan worked as a music teacher, but as a result of illness left New

York for the

healthier air of Denver, Colorado, dying there or on the way in 1885.

(3) Intensive efforts, particularly by de Valera's biographer Tim Pat

Coogan and the genealogist Joseph M Silinonte,

have failed to locate any marriage record, nor has a death record or

indeed any further significant documentation relating to Vivion Juan

been forthcoming. (4) Disappointingly, a major reassessment of de

Valera published under the auspices of the Royal Irish Academy failed

to deal with the problematic issue of its subject's paternity, indeed apparently ignoring Vivion de Valera altogether. (5)

A memoir by the late Terry de Valera, Eamon de

Valera’s son, contains what is claimed to be a definitive account of

the Hispanic origins of the family. (6) It is claimed that a

connection has been established with the Valera family of Spain, and

cousinship proven with the Marqués de Auñon. In this account it

is stated that de Valera’s father Vivion Juan was a grandson of Antonio

Valera of Seville in Spain, brother of the author and diplomat Juan

Valera. It is claimed that the family had interests in Cuba, and it was

from there that Vivion Juan moved to the United States, marrying Kate

Coll. Unfortunately, no documentation is cited to verify the connection

with the Spanish Valeras, and the tale appears to be a largely

imaginative development of de Valera’s own unsuccessful attempt to

establish a link (of which more below). At one point Terry de Valera

concedes that the name Vivion ‘does not appear to have been used’ by

the Spanish Valeras. (7) The author angrily rejects the charge that

Eamon de Valera’s parents may not have married, clearly responding to

an implication in Coogan’s biography but without naming the author.

(8) Unfortunately, it remains a fact that no trace can be found of a marriage record of Vivion de Valera and Kate

Coll, and in our hopefully more understanding times, there need be no

problem considering the probability that their son Edward or

Eamon was born out of wedlock.

Eamon de Valera's suggested Cuban

connection was in the news in recent years, with a claim by Professor

Brendan Ward of Columbia University in New York that he has tracked

down his father's baptism, communion and confirmation certificates in

Mantanza. (9) A television documentary was reportedly planned, and the present

writer would certainly be interested in examining any new evidence

found. The late Proinsias Mac Aonghusa also claimed that he had

confirmed a Cuban origin for Vivion Juan, stating that he had been

born

there in 1853 and that his father Juan Manuel owned a sugar cane estate

in Matanzas Province, but unfortunately documentation to confirm this

story is again wanting. (10) A Cuban connection is certainly a

possibility, and it should be borne in mind that the expression

'Spanish' could apply

to those born in existing or former Hispanic colonies.

The extensive papers of Eamon de

Valera are now held in the Archives Department of University College

Dublin at Belfield, and the present writer has spent some time

examining them for information which would throw light on the matter of

the statesman's paternal ancestry. (11) The substantial quantity of

material in his papers relating to

his ancestry, and particularly his paternal ancestry, shows that the

matter was of considerable importance and indeed sensitivity to de

Valera. It is clear that de Valera's mother was the prime source of the

information transmitted about his father Vivion Juan. De Valera had

been sent back to Ireland as a child to be reared by his Coll

relatives, while his mother remained in the United States and

remarried. In adulthood de Valera maintained contact with his mother,

and the subject of his father came up in

correspondence from time to time. Thus while in prison in Dartmoor in

the wake of the

1916 Rising, de Valera put several questions to his mother concerning

his father and a possible connection with certain prominent

Spanish

families bearing the surname, concluding rather wistfully, 'My own

children will be asking these questions shortly I expect'. (12)

Throughout his years as Irish

prime minister in the 1930s and even after his election as President of

Ireland in 1959, de Valera maintained the quest for information on his

elusive father. The usual pattern was that de Valera would initiate

discreet enquiries, or respond to suggested leads, following which

efforts to document Vivion Juan would be made. De Valera was

sensitive to any publicity concerning his paternal quest, expressing

regret that an apparently indiscreet contact in Philadelphia had been

the cause of the story appearing in the press. (13) It is clear that

despite the efforts of many sympathetic helpers working in the United

States and Spain, nothing conclusive was ever found. A possible link to

the family of the Spanish novelist and diplomat, Juan Valera, which

family had Cuban connections, was explored by the Irish Ambassador to

Spain, Leopold H Kerney in 1936. Kerney interviewed the Marqués

de Auñon, grandson of Juan Valera, who claimed that a brother of

his grandfather had married an Irish girl in New York. Unfortunately,

there was no recollection of anyone bearing the distinctive forename

Vivion, and both Kerney and de Valera feared that the story could be

'of recent growth'. (14)

After de Valera's election as President, he did not

as might have been expected secure a grant of a coat of arms from the

Office of the Chief Herald of Ireland. Advancing only his family

tradition of a Spanish connection, de Valera in 1965 managed via

the Cronista Marqués de Ciadoncha to secure usage of existing arms in the

form of a shield quartered with

lions rampant and stylised

crescent moons, and a bordure of x-shaped crosses, which arms were

compliantly certified by the serving Chief Herald Gerard Slevin in

1966. (15) It is important

to emphasise that use of these arms is not proof of a connection

between de

Valera and a specific armigerous Spanish family, but is merely based on

an assumption that such a link existed. De Valera's failure to secure arms from the Irish Chief Herald is ironic in light of

the fact that he had facilitated the establishment of

an indigenous heraldic authority to replace the British regime's Ulster's Office in 1943. Other Irish

Presidents, and indeed two United States Presidents have been issued with arms by Chief Heralds over the years,

although it emerged in the wake of the Mac Carthy Mór scandal in 1999 that the office had no adequate legal

authority to grant arms. (16)

As late as 1962, de Valera made

another attempt to trace a marriage record for his father and mother in

St Patrick's Church, Jersey City, in 1881. The priest replied in the

negative, suggesting diplomatically that there may have been 'neglect

of entry', but that after such a long lapse of time the task of

ascertaining the fact of marriage seemed 'well nigh impossible'. (17)

In 1963-64, de Valera's cousin Edward P Coll

was making systematic enquiries as to Vivion Juan's fate in the United

States. Coll was based in the

De Vargas Hotel, Santa Fé, New Mexico, where he seems to have

been employed, and from thence sent out

numerous requests to priests and civil registrars to search for a

burial record. Coll's form letter specified that Vivian Juan de Valera

had set out for Santa Fé in 1883 when suffering from

tuberculosis, and that a report reached the family in 1885 that he had

died and was buried in New Mexico. Coll received no positive replies to

his many letters. (18) However, it would seem that some

additional information may have been received by the de Valera family

to

shift the focus of Vivion Juan's last days from Colorado to the

adjoining state of New Mexico. And as we shall now see, New Mexico

had also come to my attention via other sources.

Even before tackling the de Valera Papers, I had

been using the growing body of genealogical records available on the

Internet in an effort to solve the mystery of Eamon de Valera's

paternal ancestry. The Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-Day Saints (Mormon) website is the world's largest free online

genealogical database, providing an invaluable resource for studying

surname distribution in the western world and many former colonial

possessions. (19)

It seemed appropriate to start by listing the locations in the which

were found the surname forms de Valera and de Valero, excluding other

variants for the time being. The specific surname forms de Valera and

de Valero were not found to be very common, and in addition to Spain,

they occurred in Mexico, Cuba, Barbados, Peru, and Venezuela. The

forms Valera and Valero, without the prefix 'de', were found

to be much more common, and while again concentrated in the Hispanic

world, in Spain, Central and South America, the Caribbean and the

Phillipines, there were some occurrences also in Germany, the

Netherlands and even Britain.

A second approach was to study

the distribution of the surname de Valera and variants within the

borders of the United States of America as recorded in the 1880 Census,

which was most efficiently done via the subscription website of the

firm Ancestry. (20) It was established that there were no occurrences

of

the forms de Valera and de Valero in the 1880 Census. Dropping the prefix,

the

following results were obtained:

Valera

12 entries (8 Pennsylvania, 2 New Mexico, 1 New York, 1 Texas)

Valero 7 entries (6 New Mexico, 1 Texas)

The

Pennsylvanian entries were clearly of German origin, while the single

New York entry related to a Claudis, recte Claudio Valera, who was born

in Cuba about 1856, and was listed as a student resident in Queens

Borough. The latter individual should certainly be borne in mind given

the claimed Cuban connection of Eamon de Valera's father. (21) However,

the significant New Mexico cluster attracts particular attention,

given the above mentioned reference discovered in the de Valera Papers.

Employing the Soundex option, whereby similarly

spelt and sounding entries are returned, the

following results were also noted in Ancestry's 1880 Census index:

Valerio

59 entries (47 New Mexico, 11 Colorado, 1 California)

Valeria 10 entries (7 New Mexico, 1 Iowa, 1 Kentucky, 1 New York)

It should be

noted that the surname forms Valerio, Valeria and Valero are also

Italian, while

Valero has a small but significant German distribution, but again the

New Mexico concentrations stand out.

Turning to the relatively rare

forename Vivian, it was found that in general in 1880

there was either a preponderance of use in favour of females or else a

rough equality, for

example:

Pennsylvania

12 males and 21 females

New York 18 males and 18 females.

However, in the

south-western states referred to above there was a preponderance of

males

called Vivian in 1880:

New

Mexico 41 males and 2 females

Texas 33 males and 22 females

Colorado 8 males and 3 females

Most of the Texas

Vivian entries feature non-Hispanic surnames, and while most of

the Colorado entries feature Hispanic surnames, 4 of the individuals

concerned are described

as having been born in New Mexico. The name derives from St Vivian, a

fifth-century French

bishop, the usual female forms being Vivien or Vivienne (Oxford

Dictionary of First Names).

Vivion spelt with an 'o', the form preferred by the de Valeras in

Ireland, is relatively

uncommon in the 1880 United States Census and is not found at all in

New Mexico.

Hispanics sometimes use the form Bibian(o) in place of Vivian(o),

reflecting the pronunciation of

the letter 'v' in Spanish, with the female forms being respectively

Viviana and Bibiana.

At this stage we can observe that

both in terms of the concentration of the surname Valera and its

variants and the use of the forename Vivian for males, New Mexico

features

very prominently. However, it should be noted that no example was found

of the use of the two names in conjunction in records relating to this

state. We

can also recollect the element of the de Valera family story which has

Vivion Juan making a final journey in the direction of Colorado and New

Mexico. This gives

further reason for at least

considering the possibility that one of these two states could in fact

have been the point of

origin of Eamon de Valera's father, with New Mexico again being the one

most strongly

flagged. Might not the ailing Vivion Juan de Valera's final journey

have been that of a man returning to his birthplace? Of course New

Mexico is the most Hispanic part of the United States, and Mexico

proper south of the border must be kept in the reckoning, while Spain

and Cuba as we have seen remain in play. In conclusion, it should be

stressed therefore that the New Mexico connection for Eamon de Valera's

family which has been advanced in this piece remains a hypothesis

requiring much further research to confirm or refute, which research is

ongoing, and will be reported here from time to time.

Sean J Murphy

7 December 2005, last amended 21 July 2008

References

(1) Tim Pat Coogan, De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow,

London 1993, pages 5-10.

(2) 'Notable New Yorkers: Eamon de Valera',

http://www.nyc.gov/html/records/html/features/devalera.shtml,

accessed

7 December 2005, revised version noted 18 July 2008.

(3) The Earl of Longford and T P O'Neill, Eamon de Valera, London 1970, pages

1-2.

(4) Coogan, De Valera, pages 8-9; Joseph M Silinonte, articles in Irish Roots,

1999-2004.

(5) Diarmaid Ferriter, Judging Dev: A Reassessment of the Life and Legacy of Eamon de Valera, Dublin 2007; references to Vivion de Valera in the index to this work all appear to refer to Eamon de Valera's son.

(6) Terry de Valera, A Memoir,

Dublin 2005, pages 157-65; references to Vivion de Valera in the index

to this work all appear to refer to Eamon de Valera's son.

(7) Same, page 159.

(8) Same, pages 167-70.

(9) Ireland On-Line, 20 November 2005,

http://breakingnews.iol.ie/news/story.asp?j=163160130&p=y63y6x836.

(10) Letter to Irish Times, 8

June 1999, and a letter to the author 20 February 2002, in which Mac

Aonghusa stated that much of what had been written about de Valera's

father is 'fiction'.

(11) De Valera Papers, Archives Department, University College Dublin, P 150,

microfilm copies. The writer acknowledges permission of the UCD-OFM

Partnership to

cite the De Valera Papers. Access to the papers is by appointment, and

for further details see http://www.ucd.ie/archives.

(12) De Valera to Mrs Catherine Wheelwright, 18 September 1916, UCD Archives P

150/172.

(13) Same to Rev Thomas J Wheelwright, 5 January 1944, UCD Archives P 150/200.

(14) Correspondence of Leopold H Kerney, Irish Ambassador to Spain, and

enclosures, 1936, UCD Archives P 150/224.

(15) Correspondence concerning de Valera coat of arms, 1959-65, UCD Archives P

150/226.

(16) Sean J Murphy, 'An Irish Arms Crisis', http://homepage.eircom.net/%7Eseanjmurphy/chiefs/armscrisis.htm.

(17) De Valera to Rev James A Hamilton,

19 December 1962, and Rev Hamilton's reply 8 January 1963, UCD Archives P 150/227.

(18) Letters of Edward P Coll, Santa

Fé, 1953-64, UCD Archives P 150/216.

(19) FamilySearch,

http://www.familysearch.org/, search facility, accessed 7 December 2005.

(20) Ancestry, http://www.ancestry.com/,

1880 Census, accessed 7 December 2005.

(21) The Ancestry site shows that Claudio

Valera was listed as an institutionalised patient in the 1900 Census,

and that he died in New York in 1902.

Back

to Irish Historical Mysteries: Contents