|

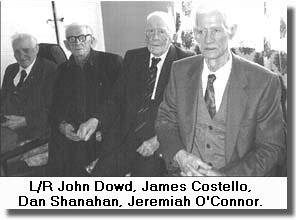

JOHN DOWD AND THE ANGLO-IRISH WAR Of the 200 men in the Abbeydorney Company of the Volunteers there are only four survivors namely, John Dowd, Dan Shanahan, James Costello, and Jeremiah O'Connor.

This is John Dowd's Story.

Early in 1918 John Dowd joined the Abbeydorney Company of the Volunteers. This company was in the Ardfert Battalion area. It was organised by Charlie Daly, Knockane, Firies. Early in 1920 the Abbeydorney volunteers decided that action would have to be taken to break Restrick's espionage network. On Thursday morning, April 22nd, 1920, the postman travelling from Ardfert to Abbeydorney on his bicycle with the mails was held up at Ballylahive Abbeydorney and the sealed mail bag taken from him. He was ordered to return to Ardfert which he did. At this time a rumour was circulating in the parish that it was the intention of the Black-and-Tans to burn down the local creamery and so members of the local volunteer company were keeping a discreet watch on the creamery during the hours of darkness. Five years previously a mill room, cream-room. office, and coal store had been added to the creamery. This rumour was later to become a reality . On Friday night, April 23rd, 1920, it was the turn of John Dowd to take up duty at the creamery. On his way he went into Lovett's public house ( now the Abbey Tavern ) to buy a bottle of lemonade. Outside the pub he stopped to have a word with Patrick Walsh, Rathscannel, a local volunteer. He was followed out of the pub by Sergeant Restrick, and Constables Lalor, and Spearman. The time was 11.30 p.m. John Dowd and Patrick Walsh were about to part when they heard voices behind them shout "halt"."Put up your hands!" in the unlit village. They found themselves covered by three revolvers and complied with the orders given by the policemen. Lalor searched both men. He found a .38 Webley revolver on John Dowd. Nothing was found on Patrick Walsh. Both men were arrested and taken to the local barracks. John Dowd was severely beaten by Restrick when he refused to give the names of the officers of the local company of volunteers, the strength of the company and their activities. Following the arrest of John Dowd and Patrick Walsh, the following local volunteers were arrested namely, Thomas Stundon, Parknageragh, Joe Treacy, Ballymacaquim, John Leen, do, Cornelius Lyons, Laccabeg. They were questioned about the taking of the mailbag but all had to be later released as no evidence could be found against them. Patrick Walsh was the last released. On Saturday, April24th, 1920 John Dowd was taken before a Special court at the police barracks, Tralee. Resident magistrate Wynne remanded him in custody to Cork Prison on the holding charge of the unlawful possession of a .38 Webley. On Thursday May 27th, 1920, he was brought before a special sitting of Tralee Court. An additional charge of the taking of the mail bag had now been preferred against him. He refused to recognise the court or give evidence. The Resident Magistrate, Colonel Crane, after hearing the evidence of Restrick, Lalor, and Spearman, ordered John Dowd to be returned for trial to Tralee Assizes in October,1920. The "Kerryman" of Saturday, May 29th,1920, describes the precautions taken during the hearing of John Dowd's case. It states: The courthouse was guarded by a large body of military and police. The military were in charge of the entrance with fixed bayonets, and trench helmets, while more police guarded the corridors with rifles". However, fate was to decree that John Dowd would not return for his trial at Tralee Assizes.National unrest was to reach such a state of intensity that the Assizes would have to be abandoned. The "Kerryman" of August 14th, 1920, has the following news item: " The political prisoners in Cork jail commenced a hunger strike on Wednesday,(11-8-1920) demanding immediate release. The number of the prisoners has not been definitely ascertained, but there are about 60, probably between 56 and 60. All the political prisoners at present in the jail have gone on hunger strike. Only six or eight of them are tried but not sentenced. The remainder are untried prisoners". John Dowd was amongst this batch. On Thursday, August 12th 1920, John Dowd and his fellow hunger strikers were joined in their strike by the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney. He was arrested while presiding at a meeting in the City Hall and courtmartialled on the charge of "being in the possession of documents, the publication of which would be likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty".On Monday, August 16th, he was sentenced to two years imprisonment by the Army Court Martial at Cork Detention Barracks. At dawn on Tuesday morning, August17th, 1920, the 56 hunger strikers were assembled in the prison yard. They were divided into two batches. The first batch of twenty eight included John Dowd. This batch were told they were being sent to Winchester Prison, England , and the second batch, which included Terence MacSwiney, were told they were being sent to Brixton Prison. MacSwiney and his batch were put on board a British naval sloop, landed at Pembroke dock in south Wales that night, and on Wednesday morning he was handed over to the governor of Brixton jail. John Dowd's batch were put on board a cattle boat and finally handed over by their armed guard to the governor of Winchester Prison. John Dowd was never to meet Terence MacSwiney again. On arrival in Brixton Prison Terence MacSwiney continued his hunger strike an event which captured the imagination of the world in 1920. He died on the 74th day of his hunger strike. He was buried in Cork on October 31st, 1920, after one of the biggest funerals in Irish history. Six weeks after his arrival in Winchester Prison John Dowd was informed that he would not stand trial at Tralee Assizes but would be tried instead by Military Courtmartial in Cork City. He was brought to Mountjoy Prison by Warders who were returning there, probably after lodging prisoners in Dartmoor. Approaching Christmas 1920, with an escort of Black-and-Tans, he was taken to the train in Kingsbridge station. He was handcuffed to an R.I.C. man named Murphy whom he thinks spent a short time in Abbeydorney. While waiting for the train to start he was addressed by a Black-and-Tan officer who told him rudely and in a terse tone that if they were attacked en route he would be shot dead. Looking back now through the mists of history to the 1920's I have no doubt that if the Tans had been attacked John Dowd would be shot instantly, thus relieving them of the burden of a prisoner. One has to take into account what Divisional Commissioner (Munster) Gerald B.F.Smyth said when the R.I.C. mutinied at Listowel Police Barracks on June 19th,1920. He stated in the course of his address "The more you shoot the better I will like you" " No policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man". "Hunger strikers will be allowed to die in jail - the more the merrier". The Tans were very edgy en route particularly at the halt at stations. Their general demeanour, conduct and alertness convinced John Dowd of the ominous situation he was in as a hostage for the safety of the Tans. His agony continued until he heard the clang of the prison gates behind him on his arrival in Cork Prison. After a few days he was transferred to Cork Detention Barracks. Here he was to spend his first Christmas away from home as a political prisoner with an uncertain future. On January 8th, he was brought before a Courtmartial consisting of five British Army Officers, When the President of the court asked him how he was pleading to the charged against him he refused to recognise the court, take the oath, or to give evidence. After hearing the evidence offered to it the Courtmartial announced they they would give their verdict at a later date. John Dowd then returned to his cell in the Detention Barracks. On January 10th 1921, he was taken to a large room in the Detention Barracks where political prisoners were assembled to hear the findings of the Courtmartial in relation to each of themselves. All the prisoners present had been found guilty of the offences with which they had been charged. As each prisoner's sentence was announced the other prisoners cheered. In John Dowd's case it was ten years. In the other cases it was from five to ten years. Finally, the death sentence was announced for the last three prisoners. There was a deadly silence. Those three prisoners had been captured in an ambush near Fermoy. They were executed a few days later. Seven days after the promulgation of the sentence a boat load of prisoners including John Dowd, was assembled. They were taken to Queenstown (now Cobh) and put on board a cattle boat en route to Portland Prison near the Dorset Coast. It was a very rough crossing in atrocious weather conditions, and John Dowd experienced his first period of sea sickness. He spent six months in this prison whose regime was very strict and harsh. In June, 1921 it was closed. With his fellow prisoners he was then transferred to Dartmoor, a prison which had become notorious in Irish history as a result of the treatment meted out to 0'Donovan Rossa and the other Fenians. Only a few years before some principals of the 1916 rising had been incarcerated in the same prison namely, Eamon DeValera, Eoin McNeill, Desmond Fitzgerald, Harry Boland, Thomas Ashe, and Austin Stack. When John Dowd and his fellow political prisoners arrived in Dartmoor the prison population was increased to 350 political prisoners. The prison was frequently enveloped in dense fog with visibility reduced to a few yards. On July 11th, 1921, the truce was declared. On December 6th, 1921, the Treaty was signed. The months passed slowly for John Dowd. In the middle of December, 1921 a rumour swept the prison that all political prisoners would be home for Christmas. The days were now short. Dartmoor was daily enveloped in dense fog. The cold weather, the bleakness of Dartmoor, and the uncertainly of the date of the release added to the discomforture of the prisoners, Christmas Eve arrived with no date fixed for their release. The prisoners became lonely and depressed at the thought of spending Christmas away from home. John Dowd was to spend his second Christmas locked up in prison. On January 15th, 1922 John Dowd and his fellow prisoners were released unconditionally from Dartmoor Prison. John and his fellow prisoners travelled by train from Dartmoor to Liverpool and by cattle boat to Dublin where he stayed for a couple of days with friends. On Saturday night, January 22nd, 1922, John Dowd arrived by train in Abbeydorney. There to greet him were members of the local volunteers together with a large crowd of people from the surrounding area. He was driven in triumphal procession to the village cross where speeches were made. Things had changed during his absence. The burning of O'Dorney had taken place. Sergeant Restrick, the most zealous R.I.C.man in Kerry in tracking down the Volunteers, was no longer there but the Black-and Tans were still in occupation of the local R.I.C.barracks, and a position of stalemate existed in national affairs. After the proceedings in the village a reception was held in John Dowd's home in Ballysheen, for his comrades in the Volunteers and his many friends. On February 18th, 1922, the Black-and-Tans and the Auxiliary Division of the R.I.C were disbanded and returned to England. On April.4th 1922, the old R.I.C. held its farewell parade in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, before disbandment. After a span of 90 years the old R.I.C.barracks, a concrete structure, was now vacant.Gone was the barbed wire and sandbags which protected its walls. School boys in the local school played around its yard and collected empty cartridged of rifle and machine gun bullets. It was the schoolboy craze to encase one's pencil in an empty bullet cartridge. This is a personal story of one of the survivors of the Irish war of Independence. Many of the stories of that period will have lost much of the authentic historical content. John Dowd's story epitomises the love of country and devotion to the cause of Irish Independence which distinguished the men and women of his generation. The younger generation who know about the Anglo-Irish War by heresay only, will be told stories which will be contaminated by myth and legend.This story by a man who took part in the action in a remarkable era which saw the dawn of freedom from foreign domination in this country, is worth preserving as a valuable historical record.

|