|

|

The first in our

series of guided tours through Ireland's regional

museums

The

Hunt Museum is in what was formerly the Limerick Customs

House. Built in the Palladian style in 1765, it was designed

by an engineer of Italian origin, Davis Dukart.

By comparison with many, the Hunt

Museum is small. It contains just over 2000 pieces that

comprised the personal collection of John and Gertrude Hunt.

John was born in England in 1900, and Gertrude in Germany in

1901. Following graduation in the early 1920s, John

established an antique business in London and very quickly

won recognition for his expertise in medieval decorative

art. Gertrude was familiar with medieval art, having grown

up surrounded by it. Like John, she recognised good

decorative art with unusual intuition. The

Hunt Museum is in what was formerly the Limerick Customs

House. Built in the Palladian style in 1765, it was designed

by an engineer of Italian origin, Davis Dukart.

By comparison with many, the Hunt

Museum is small. It contains just over 2000 pieces that

comprised the personal collection of John and Gertrude Hunt.

John was born in England in 1900, and Gertrude in Germany in

1901. Following graduation in the early 1920s, John

established an antique business in London and very quickly

won recognition for his expertise in medieval decorative

art. Gertrude was familiar with medieval art, having grown

up surrounded by it. Like John, she recognised good

decorative art with unusual intuition.

Just before WWII, the Hunts moved to Ireland. They brought

their growing collection with them, settling near Lough Gur,

in Co. Limerick. There, John became involved with the

excavations being undertaken by Prof. Sean P. O'Riordan. The

Hunts maintained their abiding interest in antiquities for

the rest of their lives. Their home was open to all and they

loved visits by neighbours who enjoyed passing the time of

day while having a look at the artifacts. Although they were

well aware of the importance and value of their collection,

the Hunts used many pieces on a daily basis. Dinner guests

were served wine from an Etruscan vessel dating from the 5th

century B.C. Gertrude used a 5000-year-old Egyptian

alabaster vase for her cut flowers, and an early Picasso

decorated the kitchen wall.

Just before WWII, the Hunts moved to Ireland. They brought

their growing collection with them, settling near Lough Gur,

in Co. Limerick. There, John became involved with the

excavations being undertaken by Prof. Sean P. O'Riordan. The

Hunts maintained their abiding interest in antiquities for

the rest of their lives. Their home was open to all and they

loved visits by neighbours who enjoyed passing the time of

day while having a look at the artifacts. Although they were

well aware of the importance and value of their collection,

the Hunts used many pieces on a daily basis. Dinner guests

were served wine from an Etruscan vessel dating from the 5th

century B.C. Gertrude used a 5000-year-old Egyptian

alabaster vase for her cut flowers, and an early Picasso

decorated the kitchen wall.

John's expertise, especially in medieval decorative art,

drew commissions from large museums and private collectors

who sought his advice regarding additions to their

collections. It also attracted the attention of young

researchers including Jorgen Andersen and Peter

Harbison. Andersen, who

published the definitive treatise on Sheela-na-gigs in 1976,

received much encouragement from John. Hunt even provided

Andersen with a picture of the Caherelly Castle

Sheela-na-gig which was used on the cover of his book, The

Witch on the Wall. The Caherelly Sheela is now on display in

the Hunt museum. Peter Harbison has very fond memories of

the Hunts. As a young, recently graduated archaeologist, he

spent quite some time cataloguing their

collection.

John's expertise, especially in medieval decorative art,

drew commissions from large museums and private collectors

who sought his advice regarding additions to their

collections. It also attracted the attention of young

researchers including Jorgen Andersen and Peter

Harbison. Andersen, who

published the definitive treatise on Sheela-na-gigs in 1976,

received much encouragement from John. Hunt even provided

Andersen with a picture of the Caherelly Castle

Sheela-na-gig which was used on the cover of his book, The

Witch on the Wall. The Caherelly Sheela is now on display in

the Hunt museum. Peter Harbison has very fond memories of

the Hunts. As a young, recently graduated archaeologist, he

spent quite some time cataloguing their

collection.

The

Hunts and their children, John and Trudy, were very anxious

that the collection should remain intact for the benefit of

future generations. Their wish was realized when the Hunt

Museum opened its doors to the public on 14 February 1997.

Artifacts in the collection range in date from the Neolithic

to the 20th century. Many Irish pieces spanning the same

time period are on display, providing a fascinating walk

through Irish cultural development from pre-historic to

modern times. The

Hunts and their children, John and Trudy, were very anxious

that the collection should remain intact for the benefit of

future generations. Their wish was realized when the Hunt

Museum opened its doors to the public on 14 February 1997.

Artifacts in the collection range in date from the Neolithic

to the 20th century. Many Irish pieces spanning the same

time period are on display, providing a fascinating walk

through Irish cultural development from pre-historic to

modern times.

Neolithic

A small Neolithic stone axe in a

handle made from the butt of an antler might have been used

to trim twigs from a branch. Its edge is still surprisingly

sharp! One of its big brothers, a stone axe from the Lough

Gur area, was used for less delicate purposes such as

felling trees to make clearances for early homesteads. Most

stone axes in the museum are of a rough-and-ready nature.

They were functional and made life a little easier for the

people who used them. Others have the qualities of elegantly

shaped works of art created by individuals who must have

spent months shaping and honing each pieceAlthough the

provenance of most Neolithic pieces in the collection is

unknown, the Hunts did record the find-spot and other

details on some pieces. One axe was found at "Holycross,"

another at "Raheen Bog, Caherguillamore, 1943."

|

|

Some include the name of the finder

too: "Tom Barry of Kyle townland, at Raheen, Herbertstown,

making a fence over edge of bog," Another was apparently

found by John Hunt himself on the "Lake Shore, John Hunt's

haggard, Lough Gur." The Neolithic is also represented in

the collection by a variety of other stone artefacts

including arrowheads, sickles, scrapers, spearheads and

maces.

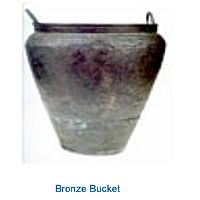

Among the most spectacular Irish Bronze Age pieces are a

shield, cauldron, and bucket or situla. Although the exact

find-spot for the shield is unknown, there is evidence to

suggest it came from Co. Antrim. The cauldron and bucket are

known to have been found in bogs in Co. Antrim in the 1880s.

All three, which date from 700 - 650 B.C., were originally

owned by a 19th century Belfast collector, T.W.U. Robinson,

until he sold them at auction to the Pitt-Rivers collection

in Dorset. John Hunt was determined that all three should be

repatriated to Ireland, and eventually acquired them in the

early 1960s.

Among the most spectacular Irish Bronze Age pieces are a

shield, cauldron, and bucket or situla. Although the exact

find-spot for the shield is unknown, there is evidence to

suggest it came from Co. Antrim. The cauldron and bucket are

known to have been found in bogs in Co. Antrim in the 1880s.

All three, which date from 700 - 650 B.C., were originally

owned by a 19th century Belfast collector, T.W.U. Robinson,

until he sold them at auction to the Pitt-Rivers collection

in Dorset. John Hunt was determined that all three should be

repatriated to Ireland, and eventually acquired them in the

early 1960s.

The shield is of the Yetholm type, named after a place in

Scotland where several shields of this variety were found in

what may have been a ritual site. It has a diameter of 64

cm. and is made from a single sheet of bronze approximately

0.5 mm in thickness. The central umbo is surrounded by 11

raised rings, between which are circles of raised bosses,

made by hammering out (repoussé) from the back of the

shield. This shield would never have been used in battle

because it is too flimsy to have withstood a blow. It was

most likely used for some ceremonial or ritual purpose about

which we can only speculate.

The shield is of the Yetholm type, named after a place in

Scotland where several shields of this variety were found in

what may have been a ritual site. It has a diameter of 64

cm. and is made from a single sheet of bronze approximately

0.5 mm in thickness. The central umbo is surrounded by 11

raised rings, between which are circles of raised bosses,

made by hammering out (repoussé) from the back of the

shield. This shield would never have been used in battle

because it is too flimsy to have withstood a blow. It was

most likely used for some ceremonial or ritual purpose about

which we can only speculate.

|

|

The bucket was found in Capecastle Bog, near Armoy, Co.

Antrim. It measures 47 x 35 cms. Made from sheet bronze, it

is of a heavier gauge than the shield. An unusual, if not

unique, feature is the repoussé decoration around the

shoulder. The two handles are held in place by bronze strips

riveted to the rim. Evidence of contemporary repair is seen

in a number of patches riveted to the body. It is not clear

if the lower section was part of the original design or was

added later.

The bucket was found in Capecastle Bog, near Armoy, Co.

Antrim. It measures 47 x 35 cms. Made from sheet bronze, it

is of a heavier gauge than the shield. An unusual, if not

unique, feature is the repoussé decoration around the

shoulder. The two handles are held in place by bronze strips

riveted to the rim. Evidence of contemporary repair is seen

in a number of patches riveted to the body. It is not clear

if the lower section was part of the original design or was

added later.

The cauldron (not shown) was also found in a Co. Antrim bog.

Having the pot-bellied shape typical of cauldrons, it

measures approximately 50 cm. in height with a similar

diameter. It is made from five bronze sheets riveted

together using conical-headed rivets. Like the bucket, two

handles are attached to the rim and, since it is

round-bottomed, it was probably suspended by the handles

when in use. However, as with the shield, the bronze sheets

from which it was manufactured are only about 0.5 mm. thick.

It seems unlikely that the handles could support the weight

of the cauldron and its contents if it were filled to

capacity. It is possible that, as with the shield, it was

used for ceremonial purposes only.Artifacts like these are

too large to lose accidentally, thus it seems likely that

all three were deliberately deposited in what, at the time,

were shallow lakes. Evidently of immense importance to the

community at the time, today we can only speculate as to the

purposes for their deposition. Whatever the reasons, they

must have been very serious!

The cauldron (not shown) was also found in a Co. Antrim bog.

Having the pot-bellied shape typical of cauldrons, it

measures approximately 50 cm. in height with a similar

diameter. It is made from five bronze sheets riveted

together using conical-headed rivets. Like the bucket, two

handles are attached to the rim and, since it is

round-bottomed, it was probably suspended by the handles

when in use. However, as with the shield, the bronze sheets

from which it was manufactured are only about 0.5 mm. thick.

It seems unlikely that the handles could support the weight

of the cauldron and its contents if it were filled to

capacity. It is possible that, as with the shield, it was

used for ceremonial purposes only.Artifacts like these are

too large to lose accidentally, thus it seems likely that

all three were deliberately deposited in what, at the time,

were shallow lakes. Evidently of immense importance to the

community at the time, today we can only speculate as to the

purposes for their deposition. Whatever the reasons, they

must have been very serious!

Iron

Age

Although the museum has a very respectable collection of

bracelets, torcs, pins, and fibulae from the Iron Age, only

a few pieces can be identified positively as Irish. Among

these are the enigmatic "Y-shaped objects." So-called for

want of a better term, their precise use remains a

mystery.

Although the museum has a very respectable collection of

bracelets, torcs, pins, and fibulae from the Iron Age, only

a few pieces can be identified positively as Irish. Among

these are the enigmatic "Y-shaped objects." So-called for

want of a better term, their precise use remains a

mystery.

Found only in Ireland, it seems likely they had something to

do with horses because associated finds, when they occur,

are readily identifiable as horse-trappings. We still

haven't been able to discover their exact purpose but, since

ornamentation is minimal, it seems probable they had a

functional rather than decorative use. The illustration

shows one of three intact Y-shaped objects in the

collection. The other two have some ornamentation at each

terminal, but the basic design, illustrated here, shows that

each terminal is pierced and notched.

Found only in Ireland, it seems likely they had something to

do with horses because associated finds, when they occur,

are readily identifiable as horse-trappings. We still

haven't been able to discover their exact purpose but, since

ornamentation is minimal, it seems probable they had a

functional rather than decorative use. The illustration

shows one of three intact Y-shaped objects in the

collection. The other two have some ornamentation at each

terminal, but the basic design, illustrated here, shows that

each terminal is pierced and notched.

Early Christian

period

The early Irish Christian period is represented by

penannular brooches, ring pins, decorated spindle-whorls, a

fragment of a quern-stone, and even a peg carved from bone,

supposedly from a cláirseach (Irish harp). Probably

the most important piece is the Antrim Cross, found in the

River Bann in the 19th century.

The early Irish Christian period is represented by

penannular brooches, ring pins, decorated spindle-whorls, a

fragment of a quern-stone, and even a peg carved from bone,

supposedly from a cláirseach (Irish harp). Probably

the most important piece is the Antrim Cross, found in the

River Bann in the 19th century.

Dating from the 8th century, the cross is equal-armed (16.8

x 16.4 cm) with rounded "necks" between each arm. Each

terminal bears a truncated pyramid-shaped boss that is

matched by a similar device in the centre of the cross. It

is apparent from the rivet-holes on each arm that they once

held decorated panels, now lost. Each boss is decorated with

red and yellow enamel as well as blue-white millefiore, the

work of a skilled craftsman. The surviving decoration is

predominantly key-pattern, but two faces of the central boss

have zoomorphic designs that may represent dogs. Although we

can't be sure, it is surmised that it was originally mounted

on a larger wooden cross.

Dating from the 8th century, the cross is equal-armed (16.8

x 16.4 cm) with rounded "necks" between each arm. Each

terminal bears a truncated pyramid-shaped boss that is

matched by a similar device in the centre of the cross. It

is apparent from the rivet-holes on each arm that they once

held decorated panels, now lost. Each boss is decorated with

red and yellow enamel as well as blue-white millefiore, the

work of a skilled craftsman. The surviving decoration is

predominantly key-pattern, but two faces of the central boss

have zoomorphic designs that may represent dogs. Although we

can't be sure, it is surmised that it was originally mounted

on a larger wooden cross.

Late Medieval

period

An entire floor of the museum is devoted to late medieval

European religious art, dating from the 11th - 18th

centuries. Despite the political changes taking place in

Ireland during the period, decorative art was not neglected.

Some fine examples of Irish work were collected by the

Hunts, including a very ornate 16th century monstrance and

some altar or processional crosses.

An entire floor of the museum is devoted to late medieval

European religious art, dating from the 11th - 18th

centuries. Despite the political changes taking place in

Ireland during the period, decorative art was not neglected.

Some fine examples of Irish work were collected by the

Hunts, including a very ornate 16th century monstrance and

some altar or processional crosses.

Although not part of the Hunt collection, the museum hosts

the best surviving example of early 15th century Irish

metalwork. The O'Dea Crosier, made for a Limerick bishop in

1418, is an example of the exquisite workmanship that

produced the Cross of Cong and reliquary shrines during the

12th century. Although made 250 years later, the crosier

demonstrates that skills had not been lost in the

intervening period. More information, as well as photographs

of the crosier, is available at

http://www.limerickdiocese.org/history/ode-cro.htm

Although not part of the Hunt collection, the museum hosts

the best surviving example of early 15th century Irish

metalwork. The O'Dea Crosier, made for a Limerick bishop in

1418, is an example of the exquisite workmanship that

produced the Cross of Cong and reliquary shrines during the

12th century. Although made 250 years later, the crosier

demonstrates that skills had not been lost in the

intervening period. More information, as well as photographs

of the crosier, is available at

http://www.limerickdiocese.org/history/ode-cro.htm

Post-Medieval

period

The

Hunt collection contains several pieces of decorative

religious art from the 17th and 18th centuries. One of the

most important is the Galway Chalice, so-called because the

maker's mark, 'EG,' is the same as that on the Galway

Corporation Sword, the symbol of office of Galway City. The

chalice dates from c.1635 when it would have been used by a

priest as a traveling chalice on house visits to the sick.

It unscrews into three components that fit into each other,

making a compact unit that is easy to carry. On the base of

the chalice is an engraved depiction of the crucified

Christ. The significance of other marks has yet to be

established. The

Hunt collection contains several pieces of decorative

religious art from the 17th and 18th centuries. One of the

most important is the Galway Chalice, so-called because the

maker's mark, 'EG,' is the same as that on the Galway

Corporation Sword, the symbol of office of Galway City. The

chalice dates from c.1635 when it would have been used by a

priest as a traveling chalice on house visits to the sick.

It unscrews into three components that fit into each other,

making a compact unit that is easy to carry. On the base of

the chalice is an engraved depiction of the crucified

Christ. The significance of other marks has yet to be

established. 19th and 20th

centuries

The Hunts' main interest was in ancient and medieval art,

but it didn't stop there. They appreciated and sought all

forms of art that demonstrated skill, craftsmanship and

artistic excellence, even when such art was not in vogue at

the time. Picasso has already been mentioned, but their

collection also contains works by Bernardo Daddi, Henry

Moore, Sir William Orpen, Giacometti and Jack B. Yeats.

Unlike Jack, his brother, William Butler Yeats, became

famous relatively early in life. His poetry and plays are

renowned throughout the world.

The Hunts' main interest was in ancient and medieval art,

but it didn't stop there. They appreciated and sought all

forms of art that demonstrated skill, craftsmanship and

artistic excellence, even when such art was not in vogue at

the time. Picasso has already been mentioned, but their

collection also contains works by Bernardo Daddi, Henry

Moore, Sir William Orpen, Giacometti and Jack B. Yeats.

Unlike Jack, his brother, William Butler Yeats, became

famous relatively early in life. His poetry and plays are

renowned throughout the world.

|

|

With encouragement from Lady Gregory, he was one of the

major contributors to a revival of interest in Celtic

mythology, albeit in a highly romanticised and sanitised

form. This literary renaissance provided inspiration for

Irish artists, many of whom made replicas of ancient Irish

artifacts. Two such pieces, dating from the late 19th

century, are in the Hunt Museum. One is a replica of the 8th

century Ardagh Chalice, and the other is based on the design

of a 9th century Hiberno-Viking penannular thistle brooch.

The originals are in the National Museum in

Dublin.

With encouragement from Lady Gregory, he was one of the

major contributors to a revival of interest in Celtic

mythology, albeit in a highly romanticised and sanitised

form. This literary renaissance provided inspiration for

Irish artists, many of whom made replicas of ancient Irish

artifacts. Two such pieces, dating from the late 19th

century, are in the Hunt Museum. One is a replica of the 8th

century Ardagh Chalice, and the other is based on the design

of a 9th century Hiberno-Viking penannular thistle brooch.

The originals are in the National Museum in

Dublin.

|

|

The excellence of many artists is, sadly, often not fully

appreciated until after their deaths. Such was the case with

Jack B. Yeats. His most prolific period was in the 1940s,

but his works have become 'collectable' only in the last 25

years or so. It is a tribute to the Hunt's foresight and

recognition of his skills that they purchased two Yeats

paintings in the 1940s while he was still relatively

unrecognized. Atlantic Drive depicts a group in a jaunting

car on a coast road, while The Master of Ceremonies captures

the pomp and circumstance of the MC announcing the next

competitors in a boxing match (Figure 11). Both are based on

sketches made by Yeats when he lived in Sligo during the

1930s.

The excellence of many artists is, sadly, often not fully

appreciated until after their deaths. Such was the case with

Jack B. Yeats. His most prolific period was in the 1940s,

but his works have become 'collectable' only in the last 25

years or so. It is a tribute to the Hunt's foresight and

recognition of his skills that they purchased two Yeats

paintings in the 1940s while he was still relatively

unrecognized. Atlantic Drive depicts a group in a jaunting

car on a coast road, while The Master of Ceremonies captures

the pomp and circumstance of the MC announcing the next

competitors in a boxing match (Figure 11). Both are based on

sketches made by Yeats when he lived in Sligo during the

1930s.

Although this article is devoted to Irish pieces in the

collection, the Hunt museum houses many artifacts from other

parts of Europe and elsewhere that would be of interest to

scholars and enthusiasts alike. One of the most important is

a model of a rearing horse from the workshop of Leonardo da

Vinci. Others include a reliquary cross owned by Mary, Queen

of Scots, a huge emerald that was the personal seal of

Charles I of England, and a Greek coin reputed to be one of

the 30 Pieces of Silver paid to Judas for the betrayal of

Christ.

Although this article is devoted to Irish pieces in the

collection, the Hunt museum houses many artifacts from other

parts of Europe and elsewhere that would be of interest to

scholars and enthusiasts alike. One of the most important is

a model of a rearing horse from the workshop of Leonardo da

Vinci. Others include a reliquary cross owned by Mary, Queen

of Scots, a huge emerald that was the personal seal of

Charles I of England, and a Greek coin reputed to be one of

the 30 Pieces of Silver paid to Judas for the betrayal of

Christ.

Useful

information:

Hunt Museum, Rutland Street,

Limerick

Phone: +353 (0)61 312833

Fax: + 353 (0)61 312834

Email: nora@huntmuseum.com

Opening hours:

10.00 - 17.00 Monday - Saturday

14.00 - 17.00 Sunday

©

Shae Clancy MMII ©

Shae Clancy MMII

Shae Clancy is a docent

researcher with the Hunt Museum

|

|

.

.