|

|

Chariotry and the road

systems in the Celtic World

Raimund Karl

Centre for Advanced Welsh and

Celtic Studies, Aberystwyth

Chariot

parts seem to exist in abundance from continental Europe

(e.g. VOUGA 1923, VAN ENDERT 1987) and Britain (e.g. RITCHIE

1995) in the La Tène period, backing up the

importance ascribed to chariots in the ancient historical

sources about the Celts - as Diodorus writes in DIO V, 29.1:

"In their journeyings and when they go into battle the Gauls

use chariots drawn by two horses, which carry the charioteer

and the warrior …" (OLDFATHER 1939, 173) Chariot

parts seem to exist in abundance from continental Europe

(e.g. VOUGA 1923, VAN ENDERT 1987) and Britain (e.g. RITCHIE

1995) in the La Tène period, backing up the

importance ascribed to chariots in the ancient historical

sources about the Celts - as Diodorus writes in DIO V, 29.1:

"In their journeyings and when they go into battle the Gauls

use chariots drawn by two horses, which carry the charioteer

and the warrior …" (OLDFATHER 1939, 173)

Also,

their existence in Ireland, even though having come under

doubt in the recent years (e.g. RAFTERY 1994), has been

recently demonstrated for at least the Early Medieval

period, and in extenso for the La Tène period as

well, the carpat of Irish literature having been

demonstrated to be a late variant of the type of vehicle

known as carpentum in the ancient historical sources

(KARL&STIFTER 2002). Of course, the few pieces that once

belonged to chariots, that have been found in Ireland

(RAFTERY 1994, 106f.) are hard to interpret and not

especially indicative for the presence of chariots, but in

combination with the much later early medieval literature,

where chariots appear in almost every kind of text, from

epic saga literature over saints lives to legal texts, their

appearance in decorative reliefs on stone monuments

(HARBISON 1992, 11) and bog roads (RAFTERY 1992, 54 ff.)

that fit well with the early medieval legal texts on roads,

clearly demonstrate the existence of chariots in Ireland in

the Iron Age. Also,

their existence in Ireland, even though having come under

doubt in the recent years (e.g. RAFTERY 1994), has been

recently demonstrated for at least the Early Medieval

period, and in extenso for the La Tène period as

well, the carpat of Irish literature having been

demonstrated to be a late variant of the type of vehicle

known as carpentum in the ancient historical sources

(KARL&STIFTER 2002). Of course, the few pieces that once

belonged to chariots, that have been found in Ireland

(RAFTERY 1994, 106f.) are hard to interpret and not

especially indicative for the presence of chariots, but in

combination with the much later early medieval literature,

where chariots appear in almost every kind of text, from

epic saga literature over saints lives to legal texts, their

appearance in decorative reliefs on stone monuments

(HARBISON 1992, 11) and bog roads (RAFTERY 1992, 54 ff.)

that fit well with the early medieval legal texts on roads,

clearly demonstrate the existence of chariots in Ireland in

the Iron Age.

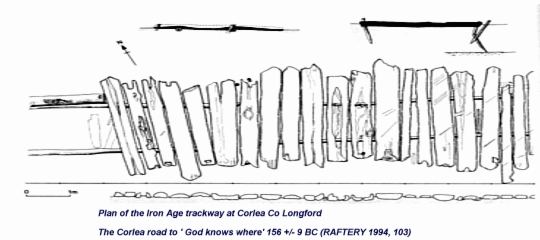

Especially

these roads, roads that seem to, at least in Ireland, lead

to "God knows where", as Raftery (1994, 101) has put it, are

of high interest for understanding not only wheeled

transport in Iron Age and Early Medieval Ireland, but also

travel, trade and communications networks in Iron Age

continental Europe. Especially

these roads, roads that seem to, at least in Ireland, lead

to "God knows where", as Raftery (1994, 101) has put it, are

of high interest for understanding not only wheeled

transport in Iron Age and Early Medieval Ireland, but also

travel, trade and communications networks in Iron Age

continental Europe.

Roads to nowhere,

everywhere

The

Irish Lawtexts tell us a lot about roads and road systems in

Early Medieval Ireland. As the road legislation in Early

Irish law stood in direct connection to the carpat (KELLY

1997, 538), and as carpat and roads that fit with these

legal norms can be documented much earlier (RAFTERY 1992, 54

ff.; RAFTERY 1994, 106 ff. und see illustration 5), it can

hardly be assumed that the legal connection between roads

and carpat developed only in Early Medieval Ireland, even

though the Irish road legislation shows, according to Kelly,

some parallels to the chapter 'De itineribus' "on

roads" in Isidor's Etymologies (KELLY 1997, 537). That

something like road legislation must have already existed in

ancient Gaul is evident from Caesar's De Bello Gallico,

where he tells us that the Aeduan Dumnorix had rented the

tolls within the Aeduan territory (DBG I, 18.3). As the term

"portoria", that Caesar uses in that specific situation, can

hardly have been limited to Harbour tolls, given the

geographical situation of the Aeduan territory, road- and

bridge-tolls will probably have made up the greater part of

the tolls rented by Dumnorix. However, as it wouldn't have

made any sense for the tribe to give away the tolls if there

hadn't been any obligation combined with this tolling of

routes, it is most likely that the care for the constant

upkeep of the roads was part of this deal. At least for high

traffic roads, we can be pretty sure that the upkeep of a

sufficent street width was part of this

arrangement. The

Irish Lawtexts tell us a lot about roads and road systems in

Early Medieval Ireland. As the road legislation in Early

Irish law stood in direct connection to the carpat (KELLY

1997, 538), and as carpat and roads that fit with these

legal norms can be documented much earlier (RAFTERY 1992, 54

ff.; RAFTERY 1994, 106 ff. und see illustration 5), it can

hardly be assumed that the legal connection between roads

and carpat developed only in Early Medieval Ireland, even

though the Irish road legislation shows, according to Kelly,

some parallels to the chapter 'De itineribus' "on

roads" in Isidor's Etymologies (KELLY 1997, 537). That

something like road legislation must have already existed in

ancient Gaul is evident from Caesar's De Bello Gallico,

where he tells us that the Aeduan Dumnorix had rented the

tolls within the Aeduan territory (DBG I, 18.3). As the term

"portoria", that Caesar uses in that specific situation, can

hardly have been limited to Harbour tolls, given the

geographical situation of the Aeduan territory, road- and

bridge-tolls will probably have made up the greater part of

the tolls rented by Dumnorix. However, as it wouldn't have

made any sense for the tribe to give away the tolls if there

hadn't been any obligation combined with this tolling of

routes, it is most likely that the care for the constant

upkeep of the roads was part of this deal. At least for high

traffic roads, we can be pretty sure that the upkeep of a

sufficent street width was part of this

arrangement.

That

roads with a sufficent width did not only exist within the

territory of one specific civitas, but also between the

territories of several civitates, thus forming "overland

routes", is yet again evident from Caesar's account. He

writes: "Erant omnino itinera duo, quibus itineribus domo

exire possent. unum per Sequanos, angustum et difficile,

inter montem Iuram et flumen Rhodanum, vix qua singuli carri

ducerentur, mons autem altissimus impendebat, ut facile

perpauci prohibere possent; alterum per provinciam nostram,

multo facilius atque expeditius, propterea quod inter fines

Helvetiorum et Allobrogum, qui nuper pacati erant, Rhodanus

fluit isque nonnullis locis vado transitur. Extremum oppidum

Allobrogum est proximumque Helvetiorum finibus Geneva. ex eo

oppido pons ad Helvetios pertinent." (DBG I, 6.1-3)

"There were but two roads that they could choose for leaving

their homeland. The one led trough the territory of the

Sequani but was, as it ran between the Rhône and the

Jura, that narrow, that hardly a single wagon could be

driven on it; and even more than that, a high mountain range

commanded the road, so that a small number of people was

sufficent to close it. The other one led trough our province

and was much easier and comfortable to use, as between the

territories of the Helvetii and the Allobroges, who have

been conquered some time ago, runs the Rhône, which

can be forded at several places. The last city of the

Allobroges, immediately at the Helvetian border is Geneva.

From this city, a bridge leads into the Helvetian

territory." That

roads with a sufficent width did not only exist within the

territory of one specific civitas, but also between the

territories of several civitates, thus forming "overland

routes", is yet again evident from Caesar's account. He

writes: "Erant omnino itinera duo, quibus itineribus domo

exire possent. unum per Sequanos, angustum et difficile,

inter montem Iuram et flumen Rhodanum, vix qua singuli carri

ducerentur, mons autem altissimus impendebat, ut facile

perpauci prohibere possent; alterum per provinciam nostram,

multo facilius atque expeditius, propterea quod inter fines

Helvetiorum et Allobrogum, qui nuper pacati erant, Rhodanus

fluit isque nonnullis locis vado transitur. Extremum oppidum

Allobrogum est proximumque Helvetiorum finibus Geneva. ex eo

oppido pons ad Helvetios pertinent." (DBG I, 6.1-3)

"There were but two roads that they could choose for leaving

their homeland. The one led trough the territory of the

Sequani but was, as it ran between the Rhône and the

Jura, that narrow, that hardly a single wagon could be

driven on it; and even more than that, a high mountain range

commanded the road, so that a small number of people was

sufficent to close it. The other one led trough our province

and was much easier and comfortable to use, as between the

territories of the Helvetii and the Allobroges, who have

been conquered some time ago, runs the Rhône, which

can be forded at several places. The last city of the

Allobroges, immediately at the Helvetian border is Geneva.

From this city, a bridge leads into the Helvetian

territory."

Thus,

there was at least one road at each side of the Rhône,

which led out of the territory of the Helvetians, of which

the one was that narrow, that hardly a single wagon could

pass it, which tells us not only that the other was much

easier and comfortable to use, but also that it was at least

wide enough for a single wagon to use it most easily, and

this one even led across the Rhône via a bridge at

Geneva. Thus,

there was at least one road at each side of the Rhône,

which led out of the territory of the Helvetians, of which

the one was that narrow, that hardly a single wagon could

pass it, which tells us not only that the other was much

easier and comfortable to use, but also that it was at least

wide enough for a single wagon to use it most easily, and

this one even led across the Rhône via a bridge at

Geneva.

Considering

the geographical situation along the Helvetian borders, and

also considering that not everywhere in the Celtic world

such geomorphological limitations existed as in case of the

Helvetian territory, it can most safely be assumed that the

territories of the other Gaulish civitates were connected by

more and most probably better developed roads and road

networks that the Helvetians with their western

neighbours. Considering

the geographical situation along the Helvetian borders, and

also considering that not everywhere in the Celtic world

such geomorphological limitations existed as in case of the

Helvetian territory, it can most safely be assumed that the

territories of the other Gaulish civitates were connected by

more and most probably better developed roads and road

networks that the Helvetians with their western

neighbours.

It

is equally evident that a well developed local road network

must have existed: „Collis erat leviter ab infimo

acclivis. hunc ex omnibus fere partibus palus difficilis

atque impedita cingebat non latior pedibus quinquaginta. hoc

se colle interruptis pontibus Galli fiducia loci

continebant…" (DBG VII, 19.1-2) „It was a gentle

hill, that was almost completely surrounded by swamps of no

more than 50 feet width. The Gauls broke down the bridges

across the swamps and, trusting in the advantages the

territory gave them, remained on the hill." It

is equally evident that a well developed local road network

must have existed: „Collis erat leviter ab infimo

acclivis. hunc ex omnibus fere partibus palus difficilis

atque impedita cingebat non latior pedibus quinquaginta. hoc

se colle interruptis pontibus Galli fiducia loci

continebant…" (DBG VII, 19.1-2) „It was a gentle

hill, that was almost completely surrounded by swamps of no

more than 50 feet width. The Gauls broke down the bridges

across the swamps and, trusting in the advantages the

territory gave them, remained on the hill."

Obviously,

the Gauls even bridged swamps Obviously,

the Gauls even bridged swamps  ,

and this sufficently solid to have an army march over it,

just to gain access to a gentle, dry hill. Would these

bridges have been simple narrow footmen crossings, that

could have been defended eassily against single enemies

advancing on them, it is hardly imagineable that the Gauls

would have broken down the bridges crossing these swamps, as

such, it is most likely that these bridges actually were

wide enough to allow a wheeled vehicle to access the hill

via them. Now, if several traffic-proof bridges were built

to gain access to a hill that was most likely used for

agricultural purposes only, and if at the same time overland

roads existed that could be used by wheeled vehicles, then

we have to assume a well-developed road system with local

and long distance routes in Gaul at Caesar's

times. ,

and this sufficently solid to have an army march over it,

just to gain access to a gentle, dry hill. Would these

bridges have been simple narrow footmen crossings, that

could have been defended eassily against single enemies

advancing on them, it is hardly imagineable that the Gauls

would have broken down the bridges crossing these swamps, as

such, it is most likely that these bridges actually were

wide enough to allow a wheeled vehicle to access the hill

via them. Now, if several traffic-proof bridges were built

to gain access to a hill that was most likely used for

agricultural purposes only, and if at the same time overland

roads existed that could be used by wheeled vehicles, then

we have to assume a well-developed road system with local

and long distance routes in Gaul at Caesar's

times.

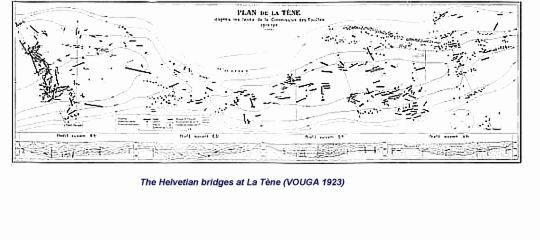

That

such a road system did actually exist, can be documented

even archaeologically within the territory of the

Helvetians. With the finds during the Jura water corrections

at La Tène, Cornaux-Les Sauges and at several other

places along the Thielle and Broye rivers in Switzerland

(SCHWAB 1989) a great number of bridges and even a

surface-metalled road from the La Tène period were

located in an area of several square kilometers. That

such a road system did actually exist, can be documented

even archaeologically within the territory of the

Helvetians. With the finds during the Jura water corrections

at La Tène, Cornaux-Les Sauges and at several other

places along the Thielle and Broye rivers in Switzerland

(SCHWAB 1989) a great number of bridges and even a

surface-metalled road from the La Tène period were

located in an area of several square kilometers.

|

|

In

Britain, the situation in regard to the road system is very

similar: "Et, cum equitatus noster liberius praedandi

vastandique causa se in agros effunderet, omnibus viis

semitisque notis essedarios ex silvis emittebat et magno cum

periculo nostrorum equitum cum his confligebat atque hoc

metu latius vagari prohibebat." (DBG V, 19.2) "As our

cavalry disbanded carelessly, to loot and to destroy the

countryside, Cassivellaunus sent his chariots against them

on all known ways and roads out of the forests, engaging our

soldiers in dangerous fights. From there on, they no longer

roamed the countryside out of fear, " In

Britain, the situation in regard to the road system is very

similar: "Et, cum equitatus noster liberius praedandi

vastandique causa se in agros effunderet, omnibus viis

semitisque notis essedarios ex silvis emittebat et magno cum

periculo nostrorum equitum cum his confligebat atque hoc

metu latius vagari prohibebat." (DBG V, 19.2) "As our

cavalry disbanded carelessly, to loot and to destroy the

countryside, Cassivellaunus sent his chariots against them

on all known ways and roads out of the forests, engaging our

soldiers in dangerous fights. From there on, they no longer

roamed the countryside out of fear, "

Even

with a vehicle with a spring suspension, as the carpentum

and most probably the Britsh essedum were, with which a

certain mobility off roads is possible, a serious attack on

cavalry using cattle driving ways or trampled paths is

hardly possible, at least not in an effectivity to strike

fear into Roman cavalry, even if this cavalry is operating

disbanded. Even narrow wagon trails seem to be insufficent

for such an attack, as is strongly restricts the mobility

and turnability of chariots, which would be necessary to

make them dangerous to cavalry, which is very mobile even on

relativy narrow paths. A rapid hit and run tactic, as seemed

to have been applied by Cassivellaunus here, is only

possible if the chariots can turn quickly to run. Even more,

it seems to be especially unlikely that an army, operating

with 4000 chariots, is able to, in the cover of a forest

(!), follow the Roman legions, which are marching on a main

road on open territory. If we do not want to assume that

Caesar invented this whole episode completely, it has to be

assumed that the british army followed the Roman legions on

the other side of the forest, most probably in the next,

more or less parallel valley, on a main, well built road

quite similar to the one the Romans were marching on (an

this road had to be able to take quite some stress, the one

the marching Roman legions and the other a lot of chariots).

From here, along equally well built side roads, connecting

the main roads across the forests separating them, the

British could mount surprise attacks against the disbanded

Roman cavalry, which could develop rapidly enough to

endanger the cavalrists. These connecting side roads must

have existed often frequently enough to allow a sufficent

number of quick surprise attacks, to really become more than

a nuissance to the Roman cavalry, it thus has to be assumed

that they were no more than a few kilometers apart. We,

thus, can assume a welldeveloped local and long distance

road network, with main and local roads being easily useable

with a carpentum or essedum, to have existed at least in

Caesarean Britain. Even

with a vehicle with a spring suspension, as the carpentum

and most probably the Britsh essedum were, with which a

certain mobility off roads is possible, a serious attack on

cavalry using cattle driving ways or trampled paths is

hardly possible, at least not in an effectivity to strike

fear into Roman cavalry, even if this cavalry is operating

disbanded. Even narrow wagon trails seem to be insufficent

for such an attack, as is strongly restricts the mobility

and turnability of chariots, which would be necessary to

make them dangerous to cavalry, which is very mobile even on

relativy narrow paths. A rapid hit and run tactic, as seemed

to have been applied by Cassivellaunus here, is only

possible if the chariots can turn quickly to run. Even more,

it seems to be especially unlikely that an army, operating

with 4000 chariots, is able to, in the cover of a forest

(!), follow the Roman legions, which are marching on a main

road on open territory. If we do not want to assume that

Caesar invented this whole episode completely, it has to be

assumed that the british army followed the Roman legions on

the other side of the forest, most probably in the next,

more or less parallel valley, on a main, well built road

quite similar to the one the Romans were marching on (an

this road had to be able to take quite some stress, the one

the marching Roman legions and the other a lot of chariots).

From here, along equally well built side roads, connecting

the main roads across the forests separating them, the

British could mount surprise attacks against the disbanded

Roman cavalry, which could develop rapidly enough to

endanger the cavalrists. These connecting side roads must

have existed often frequently enough to allow a sufficent

number of quick surprise attacks, to really become more than

a nuissance to the Roman cavalry, it thus has to be assumed

that they were no more than a few kilometers apart. We,

thus, can assume a welldeveloped local and long distance

road network, with main and local roads being easily useable

with a carpentum or essedum, to have existed at least in

Caesarean Britain.

|

|

Given

that these road systems existed, and that they, in the

archaeological record, seem to fit pretty well with the bog

roads detected in Ireland, we can safely assume that the

road system in Gaul and ancient Britain, at least in its

basic makeup, was very similar to the road system described

in the Irish lawtexts: The "highway", slige, on which

two carpait/carpenta could pass without one having to give

way to the other, the "local road",rout, on which at

least one carpat/carpentum and two riders can pass side by

side Given

that these road systems existed, and that they, in the

archaeological record, seem to fit pretty well with the bog

roads detected in Ireland, we can safely assume that the

road system in Gaul and ancient Britain, at least in its

basic makeup, was very similar to the road system described

in the Irish lawtexts: The "highway", slige, on which

two carpait/carpenta could pass without one having to give

way to the other, the "local road",rout, on which at

least one carpat/carpentum and two riders can pass side by

side  as a regional main road, the „connecting road",

lámraite, a minor road connecting two major

roads

as a regional main road, the „connecting road",

lámraite, a minor road connecting two major

roads , the „side road",

tógraite, leading to a forest or a river,

which private persons could rent, for which they then could

extract tolls from people driving cattle on them , the „side road",

tógraite, leading to a forest or a river,

which private persons could rent, for which they then could

extract tolls from people driving cattle on them  ,

and finally the „cow road", bóthar, which

still had to be as wide as two cows, one standing parallel

and one normal to the road ,

and finally the „cow road", bóthar, which

still had to be as wide as two cows, one standing parallel

and one normal to the road (KELLY 1997, 390 f.).

(KELLY 1997, 390 f.).

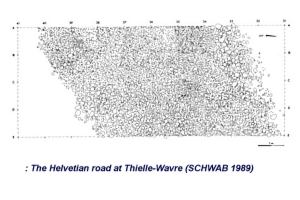

The

technique in which such roads, at least the public, larger

ones, were built can also be deducted from the Early

Medieval Irish texts, we are told that they should have a

suface constructed with branches, stones and earth (KELLY

1997, 391). The way to build roads across boggy terrain is

described as well, such a bog road, tóchar, is

described in the old Irish tale Tochmarc

Étaíne as having a foundation made of wooden

planks and branches, their surface consists of layers of

clay, gravel and stones The

technique in which such roads, at least the public, larger

ones, were built can also be deducted from the Early

Medieval Irish texts, we are told that they should have a

suface constructed with branches, stones and earth (KELLY

1997, 391). The way to build roads across boggy terrain is

described as well, such a bog road, tóchar, is

described in the old Irish tale Tochmarc

Étaíne as having a foundation made of wooden

planks and branches, their surface consists of layers of

clay, gravel and stones (KELLY 1997, 392 f.). A similar road construction technique

can be assumed for pre-Caesarean Gaul as well, and is pretty

well documented by the metalled road surface of the road in

Thielle-Wavre (SCHWAB 1989) for instance.

(KELLY 1997, 392 f.). A similar road construction technique

can be assumed for pre-Caesarean Gaul as well, and is pretty

well documented by the metalled road surface of the road in

Thielle-Wavre (SCHWAB 1989) for instance.

I am of the opinion that we have to assume that, given the

almost perfectly identical use of the carpat/carpentum on

the Continent, in Britain and in Ireland (KARL&STIFTER

2002) and the mostly similar road system in all three

mentioned areas, not only a strong technical similarity

existed within this wider central and western European area,

but that also the legislation in regard to roads and traffic

were mostly similar. Maybe the road categories were not

absolutely identical, perhaps not every class of road was

part of the legislation of every people living within this

area, but different legal types of roads can be safely

assumed, as can a "public" responsibility to keep them in

good repair, a job that required a considerable amount of

manpower several times a year (KELLY 1997, 391 f.).

I am of the opinion that we have to assume that, given the

almost perfectly identical use of the carpat/carpentum on

the Continent, in Britain and in Ireland (KARL&STIFTER

2002) and the mostly similar road system in all three

mentioned areas, not only a strong technical similarity

existed within this wider central and western European area,

but that also the legislation in regard to roads and traffic

were mostly similar. Maybe the road categories were not

absolutely identical, perhaps not every class of road was

part of the legislation of every people living within this

area, but different legal types of roads can be safely

assumed, as can a "public" responsibility to keep them in

good repair, a job that required a considerable amount of

manpower several times a year (KELLY 1997, 391 f.).

On the

highways, with traffic running simultaneously in both

directions, where, as can be deducted from the sources,

opposing traffic On the

highways, with traffic running simultaneously in both

directions, where, as can be deducted from the sources,

opposing traffic had at least to be expected

had at least to be expected ,

traffic regulations must have existed, to reduce the risk of

accidents ,

traffic regulations must have existed, to reduce the risk of

accidents ,

traffic regulations that at least determined on which side

of the road one had to drive on when going in a certain

direction. Even though we have no legal text telling us

about this, it is still possible to conclude at this traffic

regulations from the Irish epics. The passage that

demonstrates this most clearly is from the Táin

Bó Cúailnge, where the warrior Etarcumul wants

to attack the hero of the tale, the famous Cú

Chulainn: "Imsoí in t-ara in carpat arís

dochum inn átha. Tucsat a clár clé fri

airecht ar amus ind átha. Rathaigis Láeg.

‚In carpdech dédenach baé sund ó

chíanaib, a Chúcúc,' ar Láeg.

‚Cid de-side?' ar Cú Chulaind. ‚Dobretha a

chlár clé riund ar ammus ind átha.'.

‚Etarcumul sain, a gillai, condaig comrac cucum-sa

..." (O'RAHILLY 1984, 44) "The charioteer turned the

chariot again towards the ford. They turned the left board

of the chariot towards the company as they made for the

ford. Láeg noticed that " The last chariot-fighter

who was here a while ago, little Cú,' said

Láeg. "What of him?' said Cú Chulainn. "He

turned his left board towards us as he made for the ford.".

"That is Etarcumul, driver, seeking combat of me..."

(O'RAHILLY 1984, 183) ,

traffic regulations that at least determined on which side

of the road one had to drive on when going in a certain

direction. Even though we have no legal text telling us

about this, it is still possible to conclude at this traffic

regulations from the Irish epics. The passage that

demonstrates this most clearly is from the Táin

Bó Cúailnge, where the warrior Etarcumul wants

to attack the hero of the tale, the famous Cú

Chulainn: "Imsoí in t-ara in carpat arís

dochum inn átha. Tucsat a clár clé fri

airecht ar amus ind átha. Rathaigis Láeg.

‚In carpdech dédenach baé sund ó

chíanaib, a Chúcúc,' ar Láeg.

‚Cid de-side?' ar Cú Chulaind. ‚Dobretha a

chlár clé riund ar ammus ind átha.'.

‚Etarcumul sain, a gillai, condaig comrac cucum-sa

..." (O'RAHILLY 1984, 44) "The charioteer turned the

chariot again towards the ford. They turned the left board

of the chariot towards the company as they made for the

ford. Láeg noticed that " The last chariot-fighter

who was here a while ago, little Cú,' said

Láeg. "What of him?' said Cú Chulainn. "He

turned his left board towards us as he made for the ford.".

"That is Etarcumul, driver, seeking combat of me..."

(O'RAHILLY 1984, 183)

From

this passage it is as clear as it could possibly be that at

least the heroes of the Irish epics, and thus most likely

also the people who heard the tales about them, thought it

to be an invitation to combat to show the left side-board of

the chariot to another charioteer From

this passage it is as clear as it could possibly be that at

least the heroes of the Irish epics, and thus most likely

also the people who heard the tales about them, thought it

to be an invitation to combat to show the left side-board of

the chariot to another charioteer .

From this can easily be deducted that, at least in Early

Medieval Ireland, it was expected that people drive along

the left side of the road, turning their left side-board

away from the road, as else many a fight would have resulted

from simply driving along a road, as every time two carpait

would have met, the nobles on them would have assumed that

they had been challenged to combat. As it is unlikely that

this tradition would have developed in Early Medieval

Ireland, we can be pretty sure that, wherever the road might

take one, it was right to drive on the left side of the road

on the Continent and in Britain as well. .

From this can easily be deducted that, at least in Early

Medieval Ireland, it was expected that people drive along

the left side of the road, turning their left side-board

away from the road, as else many a fight would have resulted

from simply driving along a road, as every time two carpait

would have met, the nobles on them would have assumed that

they had been challenged to combat. As it is unlikely that

this tradition would have developed in Early Medieval

Ireland, we can be pretty sure that, wherever the road might

take one, it was right to drive on the left side of the road

on the Continent and in Britain as well.

"In my rear view mirror, the

sun is going down, sinking behind bridges in the

road…"

If

I now look back to ancient Gaul, Britain or Ireland with the

results of this paper in mind, I cannot help but see the sun

sinking behind bridges in the road. In my opinion, the

question is not which specific road led where, but rather

why we have largely ignored that closely knit network of

main, secondary and local roads that needs to have

criss-crossed ancient Europe, forming the backbone of what

was an early TransEuropeanNetwork for travel, trade,

communication and commerce. If

I now look back to ancient Gaul, Britain or Ireland with the

results of this paper in mind, I cannot help but see the sun

sinking behind bridges in the road. In my opinion, the

question is not which specific road led where, but rather

why we have largely ignored that closely knit network of

main, secondary and local roads that needs to have

criss-crossed ancient Europe, forming the backbone of what

was an early TransEuropeanNetwork for travel, trade,

communication and commerce.

Raimund Karl

Raimund Karl

Literature

DBG G.I. Caesar, De Bello

Gallico.

DEISSMANN 1980 M. Deissmann, De

Bello Gallica/Der gallische Krieg. Reclam-Taschenbuch

Nr.

9960, Stuttgart 1980

(bibliographisch ergänzte Ausgabe 1991).

DIO Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheke

historike.

FREY 1962 O.H. Frey und W. Lucke,

Die Situla in Providence (Rhode Island). Ein Beitrag

zur

Situlenkunst des

Osthallstattkreises. Römisch-Germanische Forschungen

Band 26,

Berlin 1962.

FREY 1968 O.H. Frey, Eine neue

Grabstele aus Padua. Germania 46, 1968, s.

317-320.

HARBISON 1992 P. Harbison, The High

Crosses of Ireland. 3 Bd., Bonn 1992.

KARL&STIFTER 2002 R. Karl, D.

Stifter, Carpat - Carpentum. Die keltischen Grundlagen

des

„Streit"wagens der irischen

Sagentradition. In: A.Eibner, R.Karl, J.Leskovar,

K.Löcker, Ch.Zingerle (Hrsg.)

Pferd und Wagen in der Eisenzeit. Arbeitstagung

des

AK Eisenzeit der ÖGUF

gemeinsam mit der AG Reiten und Fahren von 23.-

25.2.2000 in Wien. Wiener

keltologische Schriften 2, Wien 2002.

KELLY 1997 F. Kelly, Early Irish

Farming. Early Irish Law Series vol. IV, Dublin

1997.

KINSELLA 1990 Th.Kinsella, The

Tain. (15th impression) Oxford University Press, Oxford

1990.

OLDFATHER 1939 C.H. Oldfather,

Diodorus of Sicily. The Library of History. Books

IV.59-VIII.

Harvard University Press 1939 (1993

reprint).

O'RAHILLY 1984 C.O'Rahilly.

Táin Bó Cúailnge from the book of

Leinster. DIAS, Dublin 1984.

RAFTERY 1992 B. Raftery, Irische

Bohlenwege. Arch.Mitt. aus Nordwestdeutschland 15,

1992,

s.49-68.

RAFTERY 1994 B. Raftery, Pagan

Celtic Ireland. The Enigma of the Irish Iron Age. Thames

and

Hudson, London 1994.

RITCHIE 1995 J.N.G. Ritchie and

W.F. Ritchie, The army, weapons and fighting. In: M.J.

Green

(ed.), The Celtic World. London

1995, s. 37-48.

SCHWAB 1989 H. Schwab, Les Celtes

sur la Broye et la Thielle. In : 2e correction des eaux du

Jura.

Archaeologie fribourgoise 5,

Fribourg 1989

VAN ENDERT 1987 D. van Endert, Die

Wagenbestattungen der späten Hallstattzeit und der

Latènezeit

westlich des Rheins. BAR

International Series 355, Oxford 1987.

VOUGA 1923 P. Vouga, La

Tène. Monographie de la station. Leipzig

1923.

NB more than 1 Mb

NB more than 1 Mb

|

|

.

.