by Rory Braddell

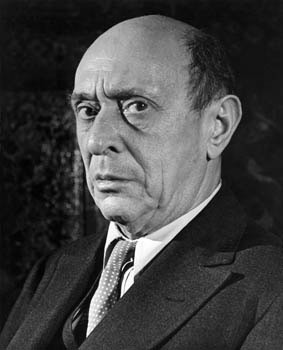

After the first performance of Gurrelieder in 1913, Schoenberg was asked if he was pleased by the apparent success of the work. He comments in an essay entitled: How one becomes lonely (1937).

Schoenberg and Atonality .... An undergraduate essay

by Rory Braddell

After the first performance of Gurrelieder

in 1913, Schoenberg was asked if he was pleased by the apparent

success of the work. He comments in an essay entitled: How one

becomes lonely (1937).

I

was rather indifferent, if not even a little angry. I foresaw

that this success would have no influence on the fate of my later

works. I had during these thirteen years, developed my style in

such a manner that to the ordinary concertgoer, it would seem to

bare no relation to all preceding music. I had to fight for every

new work; I had been offended in the most outrageous manner by

criticism; I had lost friends and I had completely lost any

belief in the judgement of friends. And I stood alone against a

world of enemies.[1]

Schoenberg’s

anger at the success of Gurrelieder is understandable if

one considers the rejection and dismissal by the musical

establishment of the majority of the music he wrote during the 13

years after Gurrelieder’s initial conception. The

implicit message is that the public would only accept a work,

which was stylistically in the tonal language of

Schoenberg’s beginnings. The musical establishment did not

accept his way of thinking and were generally unwilling to try to

understand the music. Schoenberg recounts in several of his

essays, how conductors and composers who were given his works,

returned them complaining that they were incomprehensible. In

1909 he wrote to Richard Strauss: ‘In Vienna I am at

loggerheads with everything that goes on. I can only be amiable

when I respect people; and so for this reason I only have a few

friends in Vienna’[2] Strauss categorized

Schoenberg’s orchestral pieces as ‘daring experiments

in content and sound’.[3] It is evident on this

occasion that Strauss did not comprehend the musical style and

felt that it was too risky to launch them before the conservative

audiences of Berlin.

During

the years leading up to the First World War Schoenberg was cut

off from the public and demonised by critics to the extent that,

when pieces were eventually performed, audiences came with

predetermined responses. The behaviour, of what Schoenberg calls

“the small but active ‘expert’ minority,”

clouded the judgement of what could have been impartial

audiences.[4] Schoenberg was not

treated very sympathetically by what he calls, ‘the

generals, who today still occupy the musical directorates,’

in other words, the entire musical establishment.[5] He

writes how the first performance of his Sextet Verklärte

Nacht in 1902 ‘ended in a riot and actual fights.’[6]

Similarly during the premier of the Second String Quartet in

1908, the audience disrupted the performance with outbursts of

laughter and derision. Schoenberg’s music became known for

the scandals it produced rather than for its musical worth. He

was tarnished with the label of modernism, which was seen as an

affront to the great German tradition. Criticism of

Schoenberg’s music had a nasty malicious flavour which he

often pointed out was not based on an actual understanding of the

music. One of Schoenberg’s students, Webern, writes that

‘Only those blinded by envy and ill-willed could speak of

“sensationalism mania” and the like.’[7]

The question is, what motivated Schoenberg to continue to write

even more radical music when he suffered from such isolation and

rejection?

Schoenberg’s

very theoretical understanding of his role in the evolution of

the German tradition drove him forward into what he felt was an

inevitable course. It is evident from his writings that he felt

quite isolated, but felt very justified in what he was doing.

While his opponents denied him a place in the Viennese tradition,

Schoenberg saw himself as an heir to that tradition. He writes in

1931: ‘My teachers were primarily Bach and Mozart, and

secondarily Beethoven, Brahms, and Wagner.’[8] He

goes on to discuss how he assimilated the different elements of

the German tradition and extended them in a way that led to

something new. The originality of new music is of primary

importance to Schoenberg and he writes ‘only that is worth

being presented which has never before been presented.’

Schoenberg’s code is that great work of art must convey a

new message to humanity: ‘Art means new art’.[9]

This is not new art in a revolutionary sense as Schoenberg

illustrates how the logical development of his new art is based

upon the achievements of the past. He writes: ‘I venture to

credit myself with having written truly new music which, being

based on tradition, is destined to become tradition.’[10] Schoenberg points out how composers Mahler and

Strauss, in their turn were influenced by the technical

achievements of Brahms and Wagner. There is no doubt that he saw

himself as part of that chain of composers that led back through

Beethoven and Mozart to J.S. Bach. Schoenberg’s early tonal

works all show the influences of late Romantic composers like

Brahms and Wagner. He writes how his Verklärte Nacht

(1899) is both influenced by the roving harmony of Wagner and

Brahms’ technique of developing variation. The passages of

unfixed tonality in this work, he says are ‘premonitions of

the future.’[11] Schoenberg thought

of his music at this time as being the ‘product of

evolution, and more revolutionary than any other development in

the history of music.’[12]

In

his theory of harmony, Harmonielehre (1911),

Schoenberg’s thinking about his own evolution and the

emancipation of dissonance is coloured by his ideas on harmony.

Schoenberg advocates a philosophy that seeks to balance emotional

attributes such as notions of beauty and affection with mental

logic. This he asserts with Balzac’s statement

‘that the heart must be in the domain of the head.’[13] Supreme art, he says, must show both these

attributes. In the first chapter of Harmonielehre he talks

of the danger of using aesthetic judgements based on one system

of presentation that has no relation to the logic of the whole.

Such judgments have more to do with common usage, and are

dictatorial laws that do not follow the logical development of

the principles that they are based on. Schoenberg’s theory

of harmony does not disallow the forbidden dissonances, and his

explanation of dissonance certainly gives credibility to his

arguments. It is ironic that it took until the publication of Harmonielehre

for Schoenberg to be begun to be accepted. Schoenberg in

Harmonielehre presents a theory of tonal harmony, which

focuses primarily on the music of his predecessors, and not, as

some might have expected, on atonality. Schoenberg proved to his

opponents that he had a deep knowledge and understanding of the

German tradition, and was not lacking in craft. In Harmonielehre

Schoenberg explains harmony in terms of the harmonic series in

which everything relates to the fundamental tone.

I

will define consonances as the closer, simpler relations to the

fundamental tone, dissonances as those that are more remote, more

complicated. The consonances are accordingly the first overtones,

and they are more nearly perfect the closer they are to the

fundamental. That means, the closer they lie to the fundamental,

the more easily we can grasp their similarity to it, the more

easily the ear can fit them into the total sound and assimilate

them, and the more easily we can determine that the sound of

these overtones together with the fundamental is

‘restful’ and euphonious, needing no resolution. The

same should hold for dissonance as well.[14]

Schoenberg

states that dissonance and consonance are not opposites in a

polarised sense, but are distinct in degree and not in kind.[15] Carl Dahlhaus points out that Schoenberg treats

the antithesis between consonance and dissonance as a

compositional technique that is ‘measured according to the

purpose it was supposed to fill; if it proved to be superfluous

then it could be abandoned.’[16]

According to Schoenberg, dissonance can be comprehended as the

relation of the more remote overtones to the fundamental. It is

absorbed by the subconscious and analysed accordingly. It is

easily conceivable that with some mental effort we can listen to

complex music in terms of the tonal relations relationships that

still exist despite a complete absence of the tonic.

Early

works such as: Verklärte Nacht (1899), Gurrelieder

(1900-11), Pelléas and Mélisande (1903), Six songs with

Orchestra (1904), String Quartet No. 1 (1905), and Kammersymphonie

Op. 9 (1906), are explorations of Schoenberg’s tonal

music. Schoenberg writes in My Evolution how the Kammersymphonie

was the climax of his tonal period:

Here

is established a very intimate reciprocation between melody and

harmony, in that both connect remote relations of the tonality

into a perfect unity, draw logical consequences from the problems

they attempt to solve, and simultaneously make great progress in

the emancipation of the dissonance. This progress is brought

about here by the postponement of the resolution of

‘passing’ dissonances to a remote point where, finally,

the preceding harshness becomes justified.[17]

These

early works show two very important principles of

Schoenberg’s thinking: roving harmony and developing

variation. In Verklärte Nacht, there is a very fast rate

of harmonic change, which is a product of the chromatic part

movement. Schoenberg began to see the accompanying harmony in

what he calls a quasi-melodic manner: a vertical projection of

the horizontal presentation. As in Wagner’s Tristan and

Isolde Schoenberg avoids resolution of harmony, and the

resolution is only implied and not explicitly stated. The

dissonant inflections that transformed the chords acted as pivots

and enabled Schoenberg to modulate quite quickly into a whole

sequence of distantly related keys, but retain a basic diatonic

structure. Schoenberg took advantage of the properties of the

fourths chord that has many resolutions and enables the music to

modulate freely. Schoenberg was faced with a dilemma because the

more he increased this chromatic colouring the more difficult it

became to comprehend these diatonic functions. Schoenberg writes

in My Evolution how the multitude of dissonances could not

be counterbalanced anymore by occasional returns to the tonic. It

became unacceptable ‘to force a movement into that

procrustean bed of tonality without supporting it by harmonic

progressions that pertain to it.’[18]

In Kammersymphonie Op. 9, Schoenberg used an even faster

harmonic rate of modulation that progresses through all the keys

of the harmonic spectrum in a space of time so fast, that it

becomes difficult to define the home key. This led Schoenberg to

make the decisive step in what he called the ‘emancipation

of dissonance’ and in the 4th movement of his

Second String Quartet Op. 10 (1907-8) he abandoned tonality. The

second important principle, which Schoenberg calls

‘developing variation’, is an aspect that spans his

entire career. In his essay New Music: My Music Schoenberg

states the fact that he says something once with little or no

repetition. Exact repetitions he avoided and instead he used

modified repetitions that created variation. He writes:

‘With me, variation almost completely takes the place of

repetition’[19] The technique of

varying motives and phrases he quite clearly derives from the

analysis of classical composers, and his text book on composition

bares this out.[20] The structural

factors that Schoenberg derives from the principle of developing

variation and non-repetition remain the same after his

abandonment of tonality. In the tonal period works he compresses

form, condensing the traditional four movements of the symphony

into the framework of the sonata movement. In this way the

internal repetition within movements is avoided, a principle

perpetual development emerges, and the recapitulation is

invariably varied. In the music of Schoenberg’s atonal

period, after the Second Quartet, he ran into further dilemmas.

Schoenberg’s music, without a tonal hierarchy relied

entirely on motivic architecture and became increasingly

aphoristic. Schoenberg, in his atonal period, was also faced with

the problem of freeing dissonant chords from their tendency to

resolve; even if notes are not present there is always a

functional interpretation.

In the atonal works from 1908 and leading up to the 1914-18 war,

Schoenberg developed various techniques to overcome these

problems. In the last movement of the Second String Quartet he

used text to articulate the music material. This technique is

brought to an extreme in the expressionist monodrama Erwartung

(1909), which is like an extended improvisation in continuous

recitative style where the music follows the text freely. This

work abandons, in addition to tonality, motivic unity as well,

and is athematic. The artist Kandinsky viewed line and colour as

emotional effects and removed them from their descriptive

function. Schoenberg does similar things with his music, which

mirrors the extremely expressive content of the text.

Schoenberg’s intention in Erwartung was ‘to

represent in slow motion everything that occurs in a single

second of maximum spiritual excitement, stretching it out for

half an hour’.[21] Pierrot Lunaire

Op. 21 (1912), for female vocalist and small ensemble, is a

series of short satirical pieces that are sung in a speaking

recitation called Sprechstimme. The poetry is in simple

rondo and often repeats material but the music does not follow

this pattern. Again, as in Erwartung, the

expressive content of the text dominates the music, but we find

repetition and some use even of traditional practices. Pierrot

Lunaire is a retreat away from Erwartung, which is the

extremity of the principle of non-repetition. The Three Piano

Pieces Op.11, composed earlier in 1909, employ cell like

constructions. The first of these is constructed from the cell

that appears in the first few bars and by which Schoenberg

derives all of his material. The pieces are aphoristic and

gestural and one uses repetition in the form of ostinato. These

techniques associated with the past are still a part of

Schoenberg’s thinking, but in most the music of this period

Schoenberg appears to be interested in small aphoristic cell like

constructions as apposed to large-scale structures. Ironically he

had to search for a system of presentation that could sustain

large-scale traditional forms. In his aphoristic music Schoenberg

was increasing his tendency to use all the notes of the harmonic

spectrum in a short space of time. The twelve-tone method that

evolved from twelve note motifs, ironically provided Schoenberg

with a procedure by which he was able to make structural

differentiations, not unlike tonal music. He was able to return

to the traditional structures of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms that

he so well understood.

Leon Botstein quotes an essay by Karol Szymanowski On the

Question of Contemporary Music, written in 1926.

Szymanowski describes the romantic idiom of Wagner, which

Schoenberg started out from

The

“horizontal” style of the classics, which implied in

principle the construction of pure musical “form”

changed gradually to a “vertical” style. This happened

under the influence of the dramatization of the content,

connecting music with direct psychological truth.[22]

Leon

Botstein points out that ‘the decisive step was the explicit

severing of a long tradition of parallelism between musical form

and structure and “direct psychological truth.”[23]. A step to what Szymanowski describes as

manifesting ‘vertical sound as a value in itself, not as a

function of musical “expression,”’[24] The decisive step to atomism was Schoenberg

adoption of twelve-tone serialism, however Botstein traces it

back to the Kammersymphonie Op.9, which he says alienated

an audience that had used music to ‘reinforce an

internalised belief system’. Botstein presents the theory

that Schoenberg broke the ‘parallelism between musical space

and time and the real life sensibilities’. A very radical

step away from pre-war attitudes that ‘forced a critical and

searching encounter with the present through music.’

Schoenberg does not shield his listener from ‘serious

internal dialogue’, but ‘represented a conscious desire

to write music that presents intentional difficulties for the

listener.’[25] Botstein places

Schoenberg in the heart of a ‘project of cultural and

ethical restoration, not an act of aestheticist withdrawal’.

By removing the listener’s expectation and withdrawing the

reference points offered by tonality, Schoenberg shattered the

listener’s ability to hear psychologically. It is no wonder

that the audiences who were used to certain conventions and

belief systems felt their ‘cherished ritual of culture’

was being destroyed’[26] Schoenberg rejected

this response to music based on confusion and corruption of the

arts. He writes in How one becomes lonely how he felt

about composing after 1924 when his new serial method was being

increasingly criticised. He was either described as a decadent

romanticist or a dry constructor and there was no middle ground

as always the most extreme opposites were used to describe his

music.

While

composing for me had been a pleasure, now it became dirty. I knew

I had to fulfil a task: I had to express what was necessary to be

expressed and I knew I had the duty of developing ideas for the

sake of progress in music, whether I liked it or not; but I also

had to realize that the great majority of the public did not like

it.[27]

This

is quite a stark realisation of his position and we see from

Schoenberg’s writing that he felt bereft of an audience that

had the sophistication needed to understand him. What comes

across in his writings is not a political manifesto of new art,

but his compelling sense of duty, which drove him to continue in

the manner of thinking that promoted his enhanced awareness of

the role and responsibilities of the artist.

Schoenberg was not an isolated phenomenon and is important to

stress the development in the other arts. The Expressionist

artists painted a world of unease, guilt and foreboding, which is

indicative of Schoenberg’s Ewartung and Pierrot

Lunaire. Schoenberg himself was a painter at the time of the

conception of these works and had the opportunity to spend time

with members of Der Blaue Reiter for a short time when he

lived in Munich. With Kandinsky at their head, Der Blaue

Reiter pushed the visual language of art into an abstract

world that used colour as primarily an emotional effect and not

representational. These developments owed a lot to the gathering

pace of a war in Europe and the stifling atmosphere that this

fostered. The impact of the war was to bring chaos, fear and

anger, which had a huge psychological effect over people.

Szymanowski writes how Schoenberg survived the war ‘as a

banner, an emblem, a representative of ideas which were to lead

German music out of its pre-war suffocating atmosphere towards

new achievements and conquests.’[28]

There was the consciousness amongst the post world war generation

that they had to push into the modern world so that the terrible

reality of war would not be repeated. The same philosophy was

held by the avant-garde composers of the 1950’s who grew up

during the horrors of the World War II. Schoenberg undoubtedly

confronted the struggle with modernity at a juncture in history

where Europe rapidly progressed into modern life and left behind

the romanticism of past generations.

Bibliography:

Botstein,

Leon. 1999. ‘Schoenberg And The Audience’ in Schoenberg

and his World. Edited by Walter Frisch. Princeton; New

Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Dahlhaus,

Carl. 1987. Schoenberg and the new music. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Schoenberg,

Arnold. 1984. Style and Idea, Selected Writings. Trans.

Leo Black, Ed. Leonard Stein. London: Faber and Faber, 1984

Schoenberg,

Arnold. 1983. Theory of Harmony, Trans. Roy E. Carter.

London: Faber and Faber, 1983

Stuckenschmidt,

H.H. 1977. Arnold Schoenberg. Trans. Humphrey Searle.

London: John Calder, 1977

Webern,

Anto Von. 1999. ‘Schoenberg’s Music’ in Schoenberg

and his World. Edited by Walter Frisch. Princeton; New

Jersey: Princeton University Press: 1999)

[1] Arnold Schoenberg 1984, ‘How One Becomes Lonely’ p.41

[2] Stuckenschmidt 1977, p.70

[3] Op. Cit., Stuckenschmidt, 1977, p.71

[4] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘My Public’, p.97

[5] Ibid., p.96

[6] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘How One Becomes Lonely’, p.36

[7] Anton Von Webern, ‘Schoenberg’s Music’, 1999 p.230

[8] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘National Music (2)’, p.173

[9] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘New Music, Outmoded Music, Style And Idea’, pp.114 - 115

[10] Schoenberg, 1984, National Music (2)’, p.174

[11] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘My Evolution’, pp. 80-81

[12] Ibid., p. 86

[13] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘Heart an Brain in Music’, p.75

[14] Schoenberg, 1983, p.21

[15] Ibid.,p.21

[16] Dahlhaus, 1987, p. 121

[17] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘My Evolution’, p.84

[18] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘My Evolution’, p.86

[19] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘New Music: My music’, p.102

[20] Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition (London: Faber and Faber, 1970)

[21] Schoenberg, 1984, ‘New Music: My Music’, p.105

[22] Botstein 1999, p.48

[23] Ibid., p.25

[24] Ibid., p.49

[25] Ibid., p.36

[26] Ibid., p.32

[27] Schoenberg, 1984, Heart and Brain in Music’, p.53

[28] Botstein 1999, p.47