Papers and Articles

The Loughnashade trumpet-curved trumpet or carnyx?

SIMON O'DWYER, composer and player of Bronze Age horns, outlines his experiments with the well-known Iron Age trumpet found at Loughnashade, near Navan Fort, Co. Armagh.

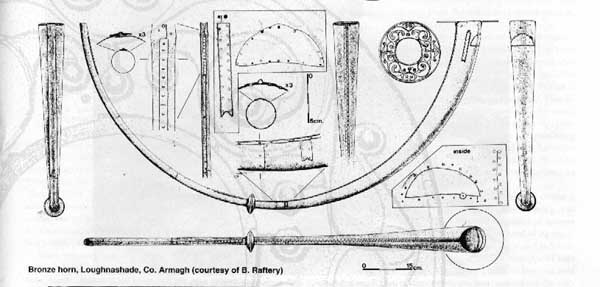

In

1993 I Was invited to play a primitive replica of the Loughnashade

trumpet at the opening of the Navan Fort interpretive centre. My curiosity was

aroused as to the proper playing position of this remarkable instrument. The

original is constructed of two curved tubes - each a quarter circle, one being

conical and the other cylindrical with a joint at the centre. As presented in

the National Museum the two parts together make an approximate semi-circle.

However, according to Eamon Kelly, the present Keeper of Antiquities at the

Museum, the trumpet when discovered was in two separate pieces.

In

1993 I Was invited to play a primitive replica of the Loughnashade

trumpet at the opening of the Navan Fort interpretive centre. My curiosity was

aroused as to the proper playing position of this remarkable instrument. The

original is constructed of two curved tubes - each a quarter circle, one being

conical and the other cylindrical with a joint at the centre. As presented in

the National Museum the two parts together make an approximate semi-circle.

However, according to Eamon Kelly, the present Keeper of Antiquities at the

Museum, the trumpet when discovered was in two separate pieces.

At the Navan Fort opening ceremony I assembled

the replica in a continuous curve as per the original display in the National

Museum (Fig. 1). From a visual point of view the long curve was aesthetically

pleasing and quite dramatic. However, it proved very difficult to play and no

matter how I held it the bell never pointed forward. When it was propped upon

a table I had to bend my head over at right angles to access the mouthpiece

which created breathing problems. If I attempted to hold it up in the air (Fig.

2) the bell pointed backwards and all the weight was concentrated down on a

small section of the mouthpiece end.

Some months later while visiting Dr John Purser

in Scotland he invited me to play the first replica he had had made of the Scottish

Iron Age carnyx. Being a contemporary of the Loughnashade trumpet and having

a similar technique in its fabrication, the carnyx when played is presented

from the mouthpiece up vertically above the player with the bell in the shape

of a boar's head pointing forward at the top (Fig. 3).

When invited again to the Navan interpretive centre

I had the opportunity to try the trumpet there in a manner similar to the carnyx.

By turning one half through 180 degrees the instrument became S-shaped. I found

that I could quite easily hold it up in the air vertically and play from a standing

or walking position. The bell then pointed forward and the entire length felt

well balanced and quite natural (Fig. 4).

Today, no-one knows how this instrument was

played, or indeed in what circumstances it was used. However, it is known that

the carnyx was essentially a war instrument as it is shown on Roman-period coins.

It is most famously seen on the Gundestrup cauldron, where three are depicted

being played in company with a group of warriors taking part in some kind of

ritual. There were four trumpets found together at Loughnashade, of which

three have been lost. Thus, an exciting scene can be imagined of a line

of trumpets high in the air leading an Iron Age army with much fanfare.

In Irish mythology the Tain Bo Froech tells of how music made by Aillil's horn

players was so wonderful that thirty of his men died of rapture.

Perhaps, as with the Late Bronze Age horns, experimentation with a proper replica will unlock the secret of this inspiring trumpet from the Celtic era of our past and allow it to resume its rightful place as an integral part of the rich and ancient musical culture of Ireland.

by Simon O'Dwyer,

Crimlin, Corr na Mona,

Co. Galway, Ireland

-353-(0) 92 48396

Published in Archaeology Ireland,

Vol. 12, No. 2, Issue No. 44, Summer 1998

ISSN 0790 892X

An Trumpa Créda

Simon O’Dwyer of Prehistoric Music Ireland updates readers on research into the Loughnashade trumpet and highlights its musical qualities.

Following the publication of the article ‘Loughnashade-trumpet or carnyx?’ (Archaeology Ireland, Summer 1998), a new exact reproduction of the original instrument was commissioned by Prehistoric Music Ireland. John Creed, master silversmith and

Following the publication of the article ‘Loughnashade-trumpet or carnyx?’ (Archaeology Ireland, Summer 1998), a new exact reproduction of the original instrument was commissioned by Prehistoric Music Ireland. John Creed, master silversmith and Scottish carnyx maker, came over to the National Museum of Ireland to examine and measure the original instrument. Between October 1997 and January 1998 he fashioned a perfect reproduction, using the same techniques as had been used in the Early Iron Age.

Scottish carnyx maker, came over to the National Museum of Ireland to examine and measure the original instrument. Between October 1997 and January 1998 he fashioned a perfect reproduction, using the same techniques as had been used in the Early Iron Age.

The name ‘An Trumpa Créda’ or ‘trumpa from the metal of the earth’, was chosen and the instrument was brought to Ireland at the beginning of February. It was officially launched on the Late Late Show and at the National Museum of Ireland. Along with the trumpa were John Kenny playing the Scottish carnyx, Dr. John Purser playing a Bronze Age horn and Maria Cullen O’Dwyer on bodhrán. Music played at the Museum performance included compositions by Simon O’Dwyer specially commissioned piece for trumpa créda and carnyx composed by  Michael Holohan. The composition was dedicated to Prof. George Eogan on the day. The concert was well attended and was filmed by Ulster Television.

Michael Holohan. The composition was dedicated to Prof. George Eogan on the day. The concert was well attended and was filmed by Ulster Television.

The trumpa was studied extensively throughout 1998, and major discoveries were made regarding its playing style and note and tone capabilities. In March 1999 it was played alongside the carnyx to open the new buildings of the Scottish Gaelic University of Sabhal Mor Ostaig on the Isle of Skye, and in May it was used as part of a study into the acoustic properties of prehistoric monuments in Orkney and Shetland. In September it had pride of place in opening Heritage Week at the National Museum of Ireland, and then returned to Scotland for a live performance at Inverness Cathedral.

This year the trumpa créda had been part of a Dúchas heritage project Millennium trail, and educational course in Kevin Street College in Dublin, and a major television series made by Café Productions for RTE and PBS in the United States. Most importantly, the trumpa featured at the Tenth International Symposium on Music Archaeology in Germany in September 2000. Among the discoveries made to date are the playing position and the relevance of the end ball plate.

Playing position

The proposed ‘S’-shape playing position which was demonstrated in the Archaeology Ireland article has indeed proven to be the most likely possibility. The trumpa, weighing only 1 kilo (2lbs), is easily lifted and held up vertically. This means that the strain is evenly distributed down through the instrument. The bell plate, pointing forward, both fulfils a visual function and enhances the sound. Because the player’s head is held back in the playing position, the trachea is straightened and tremendous volume and power can be generated from the diaphragm. The trumpa played strongly in an enclosed space can deafen a listener, and in the open air the sound can carry for miles. It is also very easy to walk or pace while playing. Thus the trumpa could be used in a parade or for leading an army into battle.

The end bell plate

While at first glance it would appear that the famous highly decorated circular disc at the bell end of the trumpa functioned solely as a visual decoration, exciting indications have emerged as to the important sound properties it may possess. When making the reproduction John Creed carried out a rudimentary test by blowing a note before he attached the end plate and then again afterwards. He described a marked increase in volume and tone with the disc attached. Further analysis has revealed that the trumpa does appear to possess unusually strong volume and tone capabilities.

It is also the case that powerful harmonics and

overtones can be played over certain notes, indicating that the bell disc may

itself be generating particular frequencies as it vibrates. This idea

was first put forward by Phillip Conyngham, the renowned didgeridoo player,

when he described the bell disc as resembling an ‘early loud-speaker’,

It is hoped that a detailed scientific study of the disc will provide

confirmation of a complex audio design, indicating an advanced knowledge of

sound in the middle Iron Age.

To date, studies on the first reproduction Iron Age trumpa have shown it to be clearly an exceptional musical instrument, requiring great expertise to design and make and providing a huge musical challenge to anybody willing to learn to play. As such it deserves recognition as one of the great Irish musical instruments.

By Simon O’Dwyer

Archaeology Ireland Winter 2000

ISSN 0790-983x Volume 14 No. 4 Issue No. 54

The Mayophone – an ancient reed instrument from the West of Ireland

Keeping us in touch with things musical in ancient Ireland, Simon O’Dwyer discusses the ‘horn’ found in Bekan Bog, Co. Mayo.

At first glance the artefact, as it was gently removed from the musical instrument cupboard no. G14 in the crypt of the National Museum of Ireland, appeared to be no more than a hollow bent stick in poor condition, with several splits along its length and some bits of corroded metal strip hanging loose. It did not seem to have much potential importance.

At first glance the artefact, as it was gently removed from the musical instrument cupboard no. G14 in the crypt of the National Museum of Ireland, appeared to be no more than a hollow bent stick in poor condition, with several splits along its length and some bits of corroded metal strip hanging loose. It did not seem to have much potential importance.

In 1857 W.R. Wilde described the artefact as a ‘horn’, and related that it had been recovered from the Bekan Bog, Co. Mayo, in August 1791 at a dept of 3m and was straight along its length at that time. D.M. Waterman described the ‘horn’ in more detail in 1969, giving measurements and suggesting the possible use of a simple reed as a sound generator. Reference to the depth of 3m of bog could indicate an age of between 2000 and 3000 years, though Dr. Eamon Kelly, Keeper of Antiquities at the National Museum, rightly pointed out that it may have been thrown into a bog hole at a much later time. The use of a reed would appear to have been very unusual for an instrument of great antiquity from Western Ireland. Such instruments would normally be thought to have first occurred in the medieval Middle Eastern area.

Our first study was conducted by a team consisting of Dr. John Purser (musicologist, composer, player of Bronze Age horns and author of Scotland’s Music), John Kenny (classical trombone and carnyx player and an authority on wind instruments), Maria Cullen O’Dwyer (musician and researcher for Prehistoric Music Ireland) and Simon O’Dwyer (researcher and player of prehistoric instruments). Without having seen the Waterman paper, John Kenny immediately identified the ‘horn’ as almost certainly a reed instrument, calling it a ‘long shawm’.

Although most of the bell was broken away, several pieces being loosely attached with string, we were able to establish that a small sliver ended in a lateral cut which was clearly the original bell end of the instrument. This was vitally important because we needed to know the exact overall length to make an accurate reproduction. The mouthpiece end had been formed, suggesting an accommodation for a cap, which was missing. This cap could have held a single or double reed. It was also clear that great woodworking expertise had been employed in the crafting. The fine carving which is visible on the inside of the broken bell was compared by Rod Cameron (master maker of Baroque flutes and dultziens) to that achieved by the makers of early Stradivarius violins. It would have been no mean feat to accurately split the wood along its length and then hollow out each half without damaging the edges. We found that a small strip or hinge had been left intact between the two parts, no doubt to ensure that they would fit back together precisely.

In essence a conical tube was achieved, almost 2m long and expanding evenly from 25mm to 75mm externally, with an internal bore decreasing from 60mm down to 15mm before a sudden reduction to 4mm. The whole piece was then bound with a spiral of fine bronze ribbon, 25mm in average width and 0.2mm thick. The splits along each side are now open as a result of age and shrinkage, but originally they would have been closed tightly enough to achieve an air seal. This would be absolutely essential if the instrument was to be played. We could see no evidence for the use of glue, which presented the possibility that the wood was worked while wet and was then dried while being held in position. A certain amount of shrinkage would occur during this stage. The halves could then be tightly bound with the bronze ribbon. If the completed tube was then soaked again in water, the wood inside the binding would swell and would probably achieve an air seal along the splits. However, Dr. Fraser Hunter of Edinburgh University believes that a long immersion in the bog would probably have removed any traces of glue.

Before undertaking the manufacture of a reproduction it was essential to establish the species of wood used for the original. Wilde had suggested willow as a possibility. Dr. Ingelise Stuijts, an expert on the microscopic analysis of wood species, established that it was actually yew, most probably from a 15 to 20-year old fast-growing tree. We await the results of radio carbon dating tests to establish approximate age and of metal analysis to identify the alloy in the ribbon. A radiocarbon result is expected in June 2002 and will be published on prehistoricmusic.com. Preliminary work on the first reproduction, made of willow, indicates a complex reed wind instrument. We have not yet established the most appropriate reed system to employ, though a modern bassoon double reed functions admirably. Research continues on this magnificent instrument.

By Simon O’Dwyer

Archaeology Ireland, Summer 2002.

ISSN 0790-892x, Volume 16 No. 2 Issue No. 60.

3rd Symposium of the International Study Group on Music-Archaeology, June 2002. Michaelstein, Germany. Paper presented, The Mayophone Study and Reproduction (PDF)

1st Symposium of the International Study Group on Music-Archaeology, May 1998. Michaelstein, Germany. Paper presented, Four Voices of the Bronze Age Horns of Ireland. (PDF)

Prehistoric Music Ireland,

Crimlin, Corrnamona,

Co. Galway, Ireland

Phone: +353(0) 949 548 396

bronzeagehorns@eircom.net

©2005,PREHISTORIC MUSIC IRELAND

In

1993 I Was invited to play a primitive replica of the Loughnashade

trumpet at the opening of the Navan Fort interpretive centre. My curiosity was

aroused as to the proper playing position of this remarkable instrument. The

original is constructed of two curved tubes - each a quarter circle, one being

conical and the other cylindrical with a joint at the centre. As presented in

the National Museum the two parts together make an approximate semi-circle.

However, according to Eamon Kelly, the present Keeper of Antiquities at the

Museum, the trumpet when discovered was in two separate pieces.

In

1993 I Was invited to play a primitive replica of the Loughnashade

trumpet at the opening of the Navan Fort interpretive centre. My curiosity was

aroused as to the proper playing position of this remarkable instrument. The

original is constructed of two curved tubes - each a quarter circle, one being

conical and the other cylindrical with a joint at the centre. As presented in

the National Museum the two parts together make an approximate semi-circle.

However, according to Eamon Kelly, the present Keeper of Antiquities at the

Museum, the trumpet when discovered was in two separate pieces.  Following the publication of the article ‘Loughnashade-trumpet or carnyx?’ (Archaeology Ireland, Summer 1998), a new exact reproduction of the original instrument was commissioned by Prehistoric Music Ireland. John Creed, master silversmith and

Following the publication of the article ‘Loughnashade-trumpet or carnyx?’ (Archaeology Ireland, Summer 1998), a new exact reproduction of the original instrument was commissioned by Prehistoric Music Ireland. John Creed, master silversmith and At first glance the artefact, as it was gently removed from the musical instrument cupboard no. G14 in the crypt of the National Museum of Ireland, appeared to be no more than a hollow bent stick in poor condition, with several splits along its length and some bits of corroded metal strip hanging loose. It did not seem to have much potential importance.

At first glance the artefact, as it was gently removed from the musical instrument cupboard no. G14 in the crypt of the National Museum of Ireland, appeared to be no more than a hollow bent stick in poor condition, with several splits along its length and some bits of corroded metal strip hanging loose. It did not seem to have much potential importance.