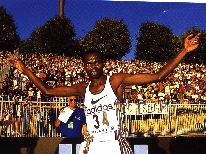

A Kenyan runner lopes majestically through the undergrowth, his training session the prelude to another record-breaking attempt. Daniel Komen, from the 8000ft high village of Nyaru, north-west of Nairobi, seems happily at home, although the habitat is not the Rift Valley, but Thames Valley in England.

A whole tribe of Kenyans can be found training around the town of Teddington during the Grand Prix season. They stay in houses rented by their manager, Kim McDonald, whose knowledge of the "Dark Continent" has made him the sport's Dr Livingston. At times there are up to 30 Kenyan athletes living by the Thames river close to Richmond Park, where Sebastian Coe still runs. The area is a suitable training environment and being close to Heathrow Airport, also allows great access to the European circuit.

For Britain, currently suffering an untypical slump in middle-distance fortunes, there is the consolation that these Kenyans have chosen a south-west London suburb as their second home. Just a few miles from the fields of Harrow, where, two generations ago, Roger Bannister trained before becoming the first-sub-four minute miler, 20 year-old Komen runs today. Yet this youngster can run two sub-four-minute miles, back-to-back, with no rest.

In September at the Italian resort of Rieti, Komen rewrote the record books. Frustrated by having to watch the Olympics on TV after failing to qualify for the Kenyan team, Komen poured his pent-up energies into a 3000m race. His time of 7:20.67 meant seven-and-a-half laps at an average of 58.76 seconds per lap. According to Track & Field News, the time equates to 7:55.92 for the full two miles; back-to-back miles averaging 3:57.96. Incredible. It was the culmination of an amazing post-Olympic campaign by Komen. The rest of the world's athletes, still recovering from Atlanta, were staggered by his performances. None more so than the Ethiopian Haile Gebrselassie, the 10,000m gold medallist and world 5000m record holder, who Komen destroyed with a display not seen at this level since Steve Ovett made John Walker step off the track during the 1500m at the 1977 World Cup. For once, the clock hardly mattered, but when Komen crossed the line, with the Ethiopian broken in his wake, his time of 12:45.09 was just 0.70 seconds outside Gebrselassie's world record.

Noureddine Morceli, the Olympic 1500m champion, was the next to feel the youngster's firepower, losing his first race for two years over 3000m in Brussels. Then Komen beat the Moroccan Salah Hissou, the new world 10,000m record holder. over 5000m at the IAAF Grand Prix final in Milan to clinch the overall Grand Prix title and the biggest cheque in track and field history - $ 250.000.

Although many athletes were hoping that Atlanta would provide future financial security, the man who missed it all has done better than most. One estimate is that Komen earned around $400,000 in a month during his "purple patch". This one season has set Komen up for life and allowed his mother to give up her job selling potatoes by the roadside.

No-one could accuse the success of going to his head, though. "It was a nice way to end the season but I think I still have room for improvement before I am a good runner," said Komen, a modest young man with a polite manner. He does not insist on the superstar treatment so many American and European athletes now demand from meeting organisers.

Komen joined McDonald and his Kenyan colleagues for the IAAF's Meeting of Solidarity for Sarajevo. A day after his victory (and huge pay day) in Milan, Komen stood patiently by the roadside in Bosnia waiting for a bus. When the vehicle finally arrived he insisted that a group of British journalists take the remaining seats before him. "You look cold," he said. Even when the bus splashed him with a puddle as it pulled away he did not complain.

Komen's post-Atlanta record-breaking spree mirrors that of his mentor Moses Kiptanui who broke two world records in three days after missing Barcelona with a knee injury. "I'm very happy for Daniel," said Kiptanui. "He will run under 12:40 for 5000m next year.”

McDonald, who also helps Komen with his training, is also convinced of his client's awesome potential. "I think he could ultimately have a range between 3:32 [for I500m] and 26:30 [for l0,000m]," said the Englishman who has worked with some of the world's greatest distance runners, including Ovett, Grete Waitz and Liz McColgan. Komen failed to make Kenya's Atlanta team not because he was injured but simply because he finished outside the first three in the "sudden-death" trials. Having also missed out on the 1995 World Championships in Goteborg, it was particularly disappointing. Komen suspects (and McDonald agrees) that he may run better at sea-level than at altitude. Yet the 13:29.33 Komen ran in Nairobi in 1994 broke John Ngugi's world altitude best by more than a second. It seems hard to believe that Komen will not quality for next year's IAAF World Championships in Athens and have the chance to win major medals.

Komen has been earmarked as a future world-beater since finishing second in the junior race at the 1993 World Cross Country Championships. In 1994 he won the 5000 and 10,000m at the World Junior Championships in Lisbon, succeeding Gebrselassie as.double champion. Those performances also have their roots in a setback. “-I should have gone to the World Junior Championships in Seoul in 1992," Komen explained. "But I was sixteen and inexperienced and I was removed from the team. I was very disappointed but I went home to prove that I was a good runner.”

The first proof of that came when Komen pushed Kiptanui to the 5000m world record in Rome last year. Komen was leading coming into the homestraight but Kiptanui surged past to win in 12:55.30 with Komen second in 12:56.15, also inside Gebrselassie's then world record of 12:56.96. "That record belonged as much to Daniel as to me," said Kiptanui. "Without him I could never have broken it. It was then that people appreciated how great a runner Daniel had the potential to be."

Watching Komen in action his utter fearlessness shines through. He thinks anything and everything is possible. "The young ones are now training with world champions and they feel it is natural that they will be as good as them," explained Kiptanui. a self-appointed guardian for the next generation of great African runners. "Kenyans don't set limits like the Europeans and Americans."

Komen was brought up in the Rift Valley where there is no public transport and few private cars. He saw the likes of Kiptanui, and what running had brought him, and decided to dedicate himself. "Because of the economic rewards available Kenyan runners are prepared to work very hard," Kiptanui admitted. Inevitably, the burn-out rate among Kenyans is also high. They run too fast and too often, frequently breaking records five years earlier than they should. Many of these young talents can lead a butterfly existence. But under the guidance of the wise Kiptanui (now a near veteran at 26!) and the shrewd McDonald you get the feeling that young Komen may be around for a few years yet. We should all sit back and enjoy his prime.

Duncan Mackay is a Brirish athletics writer contriburing regularly to The Observer and Guardian newspapers.