The Drag Rake

This rake was used for gathering up small bunches of hay or corn after being cut. Part of the triangle shaped handle is missing. Source: Kieran Costello.

Sickle

The sickle was used to cut the corn. An armful of corn was held in the left hand and cut with the right hand. About 6 or 7 armfuls were put together to form a "sheaf" and this was tied with a handful of corn stalks. The sheaves were put standing up to dry them. They were propped against each other in pairs. Three pairs were put together (6 sheaves) in a "stook."

Later on, before the corn was drawn in to the farmyard, the stooks were built

into "stacks" There were about 10 stooks in a stack.

Source: Tony Coady.

Scythe Stone

This scythe stone was used to finish edging with a scythe. The scythe was first

edged with a carrabrundum stone. The final edge was put on by rubbing each side

of the blade with the scythe stone. Some people made their own scythe stones.

They shaped a piece and glued a strip of fine sand to each side. The sand was

got from the bed of the river Nore, around Lismaine Bridge.

Source: Tony Coady.

Cutting Corn

Corn was cut with a binder. The proper name for a binder was a "reaper and binder" becasue it cut the corn and bound the sheaves. These had been two separate jobs before the binder was used. The binder was pulled by a pair of horses. There was a large wheel with beaters that directed the corn onto the blade. When it was cut it passed along canvass belts and was tied into sheaves. The sheaves were thrown out the side of the binder.

People came behind the binder to put the sheaves standing in "stooks". Jerry Bergin remembers having a Woods binder but the most common binder was a Massey Harris. Jerry told us that at the beginning of the century most of the parts of a new binder arrived in wooden crates. The binder had to be assembled by a local person.

Mick Grace's granduncle, (also Mick Grace) was a "genius at Binders".

Cutting the Corn With a Binder

This photography was taken at Kennys Seskin in 1945. It shows Mick Maher,

Mikey McGrath and Mikey's father, "after a binder".

Source: Mary Maher.

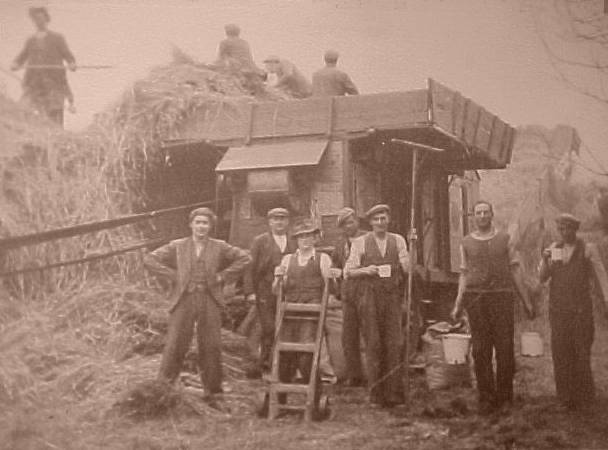

Steam Engines and Threshing

This photograph was taken at a threshing at Big Ned Campion's, Balleen in 1945, on the 10th of November. Ned is bringing out beer to the men in two enamel buckets.

Included in the photograph are:

On the mill (left to right):

Nick Cahill, Danny Skehan, Bobby Slattery, Paddy Purcell.

On the ground (left to right):

Tom Doyle, P. Carey, P. Cuddihy, Tim Fitzpatrick, Ned Campion and Richard Slattery.

Geoff Brennan told us that in 1907 his grandfather bought a new steam engine. It was shipped over from England and exhibited at the Spring Show. When the show was over his father drove it back to Castlecomer.

He left the R.D.S. at six o'clock on Friday evening and reacher Castlecomer at six o'clock on Sunday morning. They had to drive it slowly through the cobbled streets of Dublin. He was told that about 7 or 8 new engines set out from Dublin that day. They split up at different places along the way - Kilcullen, Athy, etc.

Geoff's own engine was a McLaren built in Leeds. The mill was a Ransome. Bergins of Blackwood (Jerry and Pake) bought a second-hand steam engine in 1943 from Nicky Dooley of Conahy.

The sign of the Clayton and Shutterworth engine was a brass horse. Bergins engine threshed around Blackwood, Rathbeagh and Conahy depending on the weather. Steering an engine was difficult because the wheels were turned by chains. They had special iron grips to bolt onto the wheels so that they could drive the engines into a wet field.

When the engine arrived at the farm, it took about half an hour to get up steam. The best fuel was good sea coal, but during "the Emergency" (World War II), it was very hard to get coal. The farmer had to supply the coal for the engine. At that time, coal cost about 2 s per cwt. (That's about 12c per 50kg. in modern money) Some engines were very hard on coal and water.

Geoff remembers a farmer describing one engine: "You'd need Sutton's Coalyard and the River Nore to keep it going!" Sometimes timber was used, but some timber didn't burn very well. When coal was scarce and fuel was low some engine drivers would take down a wooden gate on their way home. The gate would be left on the road. The engine would be driven back and forth over it a couple of times to break it up. It was then thrown into the fuel box and some poor farmer was at the loss of the gate.

At about ten or eleven o'clock in the morning everyone working on threshing would get a mug of beer each. The men on the straw and the men pitching sheaves had very thirsty work. They would get a mug of beer with their dinner and another in the evening. The dinner was usually bacon and cabbage, but some big farmers might have a leg of beef, boiled.

They would usually buy a quarter beer (quarter barrell of beer) for the threshing. This would cost about 7/6 p (45c in modern money). A quarter barrell was 8 gallons. Smithwicks brewed a special cheap threshing beer. It was a single x grade. Geoff remembers that both the smell and the taste was awful.

Most of the larger farms would have one and a half or two days threshing. Sometimes they would have one day and a second day about a month later. There would often be a half day's threshing in the spring. This would often be oats. It would be cut before it was ripe and would ripen in the straw.

There were several types of "black oats" threshed in the spring. Jerry Bergin remembers "black supreme" - the straw made a very good thatch - and McGull (?) and Black Turtree(?). Geoff Brennan said most of the spring threshing was for seed and there was also barley and wheat. This was especially during the War Years when the government forced farmers to till a certain amount of land - compulsory tillage. He remembers the spring threshing for another reason too. The corn was always full of rats after the winter.

Other engines in the area

Tommy Butler, Freshford had a Ransome, Simms and Jeffries.

Purcells of Ballyragget had a compound Ransome.

People were usually very proud to have a steam engine in the family. There was a saying which shows how important a steam engine was: "A priest in the family is nearly as good as an engine".