|

Capture of Mallow Barracks Provokes Reprisals (Irish War of Independence - Second Cork Brigade) |

|

Mallow

had been a garrison town for several hundred years. Eight miles to the north

lay Buttevant where one of the largest military barracks in the country was

located. Not far from Buttevant were the great military training camps of

Ballyvonaire, while nineteen miles to the north-east was Fermoy with its large

permanent military garrisons and huge barracks adjacent to the big training

centres of Kilworth and Moorepark. Twenty miles to the south-east was the city

of The idea

of capturing the barracks came from two members of the Mallow I.R.A. Battalion,

Dick Willis, a painter, and Jack Bolster, a carpenter, who were then employed

on the civilian maintenance staff of the barracks which was occupied at the

time by the 17th Lancers. Willis and Bolster were able to observe the daily

routine of the garrison and formed the opinion that the capture of the place

would not be difficult. They were instructed by their local battalion officers

to make a sketch map of the barracks. After that was prepared Liam Lynch and

Ernie O'Malley went with Dick Willis and Tadhg Byrnes to Mallow to study the

lay-out of the surrounding district. Among the details of the garrison's

routine that Willis and Bolster reported to the Column leaders, was the

information that each morning the officer in charge, accompanied by two-thirds

of the men, took the horses for exercise outside the town. It was obvious to

the two Mallow volunteers that this would be the ideal time for the attack. Situated

at the end of a short, narrow street and on the western verge of the On the

morning of September 27, at their Burnfort headquarters, the men were ordered

to prepare for action. Under cover of darkness they moved into the town and

entered the Town Hall by way of the park at the rear. The eighteen men of the

column were strengthened by members of the Mallow battalion, A number of men

were posted in the upper storey of the Town Hall, from which they could command

the approaches to the nearby R.I.C. barracks. in the event of the RIC going to

the assistance of the military. Initially it was planned that Willis and

Bolster would enter the military barracks that morning in the normal way,

accompanied an officer of the column who would pose as a contractor's overseer.

The officer was Paddy McCarthy of Newmarket who, a few months later would die

in a gun battle with the Black and Tans at Millstreet. McCarthy,

Willis and Bolster entered the barracks without mishap. Members of the garrison

followed their normal routine, with the main body of troops under the officer

in charge leaving the barracks with the horses. In the barracks remained about

fifteen men under the command of a senior N.C.O., Sergeant Gibbs. Once the

military had passed, the attackers, numbering about twenty men and led by Liam

Lynch, advanced towards the bottom of By that

time the majority of the attacking party was inside the gate. Military

personnel in different parts of the barracks were rounded up and arms were

collected. Three waiting motor cars pulled up to the gate and into them were

piled all the rifles and other arms and equipment found in the barracks. In all

some twenty-seven rifles, two Hotchkiss light machine-guns, boxes of

ammunition, Verey light pistols, a revolver, and bayonets, were taken away. The

prisoners were locked into one of the stables, with the exception of a man left

to care for Sergeant Gibbs. The whole operation had gone according to plan,

except for the shooting of the sergeant. Twenty minutes after the sentry had

been overpowered the pre-arranged signal of a whistle blast was sounded and the

attackers withdrew safely to their headquarters at Burnfort, along the mountain

road out of Mallow. Expecting

reprisals, the column moved to Lombardstown that night, and positions were

taken up around the local co-operative creamery as it was the custom of the

British to wreak their vengeance on isolated country creameries after incidents

such as what had just occurred. The Mallow raid, however, was to have greater

repercussions than the destruction of a creamery and co-operative stores. The

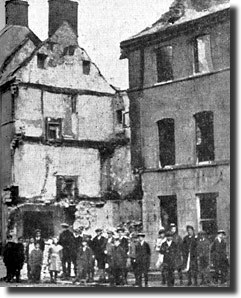

following night, large detachments of troops from Buttevant and Fermoy entered

Mallow. They rampaged through the town, burning and looting at will. High over

the town, the night sky was red with the flames of numerous burning buildings.

The

raiders first descended upon the Town Hall. As in the majority of towns, the

building was the centre of the administrative and social life of the district.

A lorry load of uniformed soldiers, frenzied and officer less, gathered in

front of it. Petrol was liberally sprayed all over the large building. Within a

short space of time the hall was a mass of flames. Warming to their task the

British next set fire to the drapery establishment of Mr. J.J. Forde, the Bank

Place residence of Town Clerk, Mr. Wrixon and with it the pharmacy of his son,

which was in the same building. Firing their weapons wildly, the British

continued their orgy of destruction. Up in the flames went the hotel of Mr.

George Hanover, the boot and shoe establishment of Mr. Thomas Quinn, the

merchant tailor's shop and residence of Mr. R. M. Quinn, the drapery shop of

Mrs. Cronin, the residence of Mr. Stephen Dwyer at West End, the garage and

premises of Mr. W. J. Thompson and finally the giant creamery of Cleeves which

gave employment to three hundred people in Mallow. Townspeople ran through the

blazing streets, in search of refuge. A number of women and children were

accorded asylum in the nearby convent schools. Another group of terrified

women, some with children in arms, took refuge in the cemetery at the rear of

St. Mary's Church, where they knelt or lay, above the graves. It was a night of

terror such as which had never before been endured by the people of Mallow. The

extent of the wanton destruction outraged fair-minded people all over the

world. Details of the havoc that had been wrought and pictures of the scenes of

destruction were published worldwide. The Times

of London printed the following editorial: “Day by day the tidings from The authorities would have been fully entitled,

after the raid, to arrest on suspicion of complicity any townsfolk against whom

a prima facie case could be established. No complaint could have been made had

they dealt summarily with any insurgent caught in possession of arms. They were

not entitled to reduce to ruins the chief buildings of the township and to

destroy the property of the inhabitants merely as an act of terrorism”. On the

following Sunday morning St. Mary's Parish Church was crowded for eight o'clock

Mass. Canon Corbett, parish priest of Mallow addressed the people from the

pulpit. In a voice that shook with emotion he described the scenes he had

witnessed on Mallow's night of terror: “The rush of frantic women and children to my

door at midnight asking, for God's sake, to provide them with some place of

safety or refuge; bullets hissing over our heads as I tried to stow them into

the Convent School; another crowd in St. Mary's cemetery—mothers with infants

at their breasts sitting on the family burying ground, as if they thought their

dead could aid them. Splendid business premises burned to the ground, and a

winter of unemployment made sure for hundreds by the burning of Cleeve's

factory. These are amongst the signs of victory, won not by Zulus or Sioux

Indians, but by Englishmen; the great victory of Mallow at 'Reprisals' they said by the civil and military

authorities. They are not reprisals. They are, as Mr. Arthur Griffith points

out, a calculated policy to goad our people into insurrection now as in 1798,

an excuse for drenching the country in blood. I have only to repeat the advice

of our good Bishop: ' Be patient.' God sees all and, in His own good time, will

deliver His people who trust in Him”. With these words, Canon Corbett broke down and

left the pulpit.

|

|

|