Tom Barry Leads West Cork Flying Column to Victory at Crossbarry

The monument at the site of the Battle of Crossbarry where major losses were inflicted on British forces.

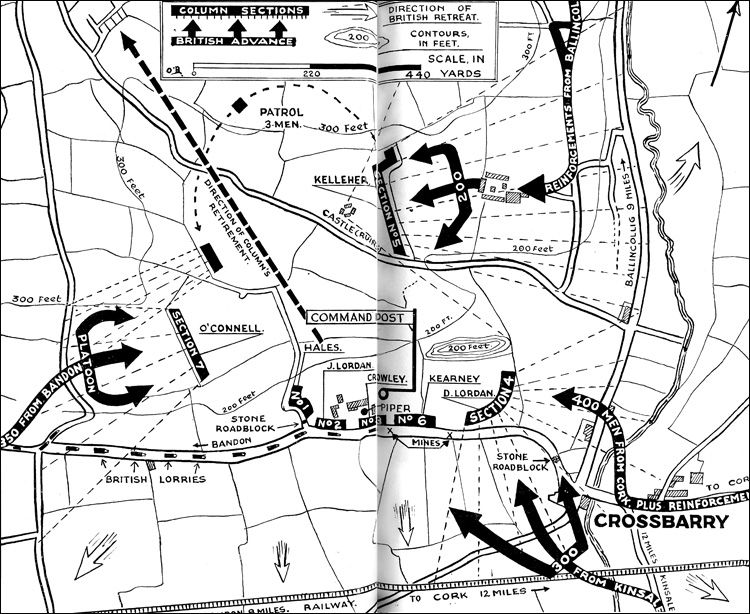

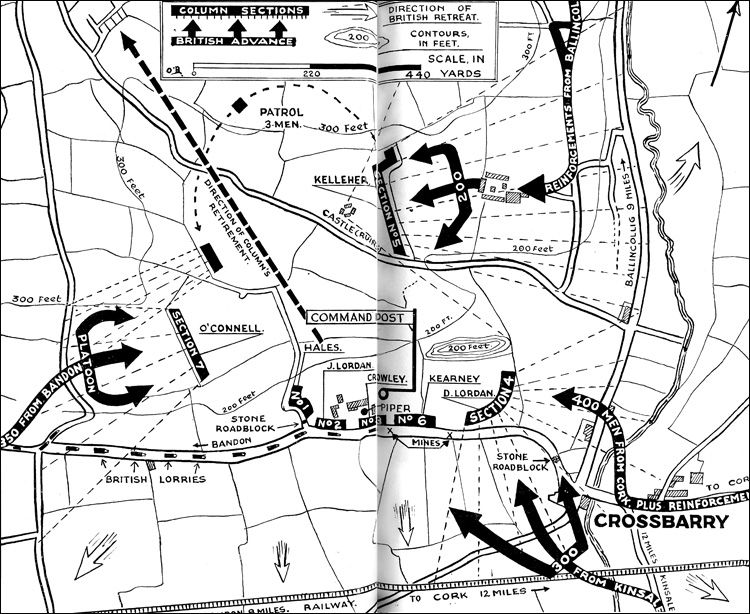

On March 19, 1921, the Third West Cork Flying Column of the IRA, under the command of the legendary Commandant General Tom Barry, achieved an extremely significant victory at Crossbarry, situated about twelve miles south-west of Cork city.

A huge encircling operation involving over 1,000 British troops and 120 Auxiliaries was mounted in an attempt to finally eliminate this troublesome column, which at that time was operating at a total strength of 104 men. Although vastly outnumbered, Tom Barry took the calculated risk of engaging in a stand-up fight with the enemy. At the end of the battle there were at least thirty-nine British soldiers (including five officers) dead and forty-seven wounded, as against three IRA men dead and two wounded.

As a result of the information they had got from a volunteer captured at the Upton ambush in February, 1921, the British military were aware that the West Cork Brigade headquarters was situated in the Ballymurphy area.

The British devised a plan to surround the Ballymurphy townland area using troops from Bandon, Cork, Ballincollig, Kinsale and Macroom. The troops were to be transported to within four miles of the area where half of the troops would dismount and advance on foot in a line towards Ballymurphy. Every house in the area would be raided all adult males arrested The soldiers on foot were to interchange periodically with those in the lorries, thus ensuring fresh troops throughout the operation.

The encirclement began about 1 a.m. on the morning of March 19th., 1921. The troops involved were the elite of the British military forces in Ireland at that time, many of them having seen action in the first World War. They were drawn from the Hampshire Regiment (stationed in Cork) the Essex Regiment (stationed at Bandon and Kinsale) and the infamous Auxiliaries (all ex-World War officers) based in Macroom.

Commandant General Tom Barry was awakened at 2.30 a.m. and told that the sound and lights of lorries were to be heard and seen in the distance. He immediately organised his men. 'I had to decide without delay whether to fight or to retire and attempt to evade action.' It wasn't an easy decision, because any section could be caught while retiring, possibly with heavy casualties as a consequence. Furthermore, the shortage of ammunition, demanding a swift and intensive fight at close quarters, was a major problem. He quickly decided they would stand and fight together.

Fearing encirclement by the enemy, he spoke to the column indicating 'that we would first smash one side of the encirclement on the Crossbarry road, and then deal with the others; above all no man or section was to retire from their position, and all were assured that they would be quickly reinforced if and when attacked.

Barry had to plan and plan quickly. His attack had to be decisive and delivered in such a way as to break the encirclement. The one hundred and four IRA men were divided into six sections in the form of a triangle, with section seven at the other side of the road (later moving into position to form a square). Communication between Barry as Column Commander and the other officers and the various sections was to be maintained by runners. The command post was movable between the centre sections.

Ironically, troops had missed out on the capture of the Brigade Intelligence Officer Sean Buckley during the initial round-up. He was taken prisoner at a nearby farm but was fortunate in that it was members of the Hampshire Regiment that had conducted the raid rather than members of the Essex Regiment from Bandon, to whom he was well known.

Harolds' farmyard where 'The Piper of Crossbarry' Flor Begley marched and played martial airs on his warpipes throughout the battle .

Shortly after the raiding party left the farmhouse, firing was heard across the bog at Ballymurphy. Another raiding party, led by a Major Hallinan had approached the farmhouse of Denis Forde, which had been brigade headquarters for some months. Present at the time was Charlie Hurley, the Brigade O.C. When the Major hammered at the door demanding entry, Hurley rushed down the stairs and fired through the door, wounding Major Hallinan. He then tried to escape through the back door. Just as he got outside the door, he was shot through the head by a soldier running to cover the rear of the house. The shots that Charlie Hurley fired, and those that killed him, were effectively the first shots of the Crossbarry Battle.

Crossbarry was the largest and most important battle in West Cork, if not in Ireland, during the Anglo-Irish war, resulting in an historic victory for the IRA and a demoralising defeat for British occupation forces. Each member of the Flying Column had only 40 rounds of ammunition when the battle commenced.

Shortly after theraiding party left the farmhouse, firing was heard across the bog at Ballymurphy. Another raiding party, led by a Major Hallinan had approached the farmhouse of Denis Forde, which had been brigade headquarters for some months. Present at the time was Charlie Hurley, the Brigade O.C. When the Major hammered at the door demanding entry, Hurley rushed down the stairs and fired through the door, wounding Major Hallinan. He then tried to escape through the back door. Just as he got outside the door, he was shot through the head by a soldier running to cover the rear of the house. The shots that Charlie Hurley fired, and those that killed him, were effectively the first shots of the Crossbarry Battle.

As already mentioned, the alarm was raised at 2.30 a.m. when the rumble of lorries was heard by the sentries. All sections were alerted and the column was on parade before 3 a.m. They then moved to a field behind Beasley's house at the western end of the ambush position. The engineering party, accompanied by a protection unit, then moved off towards Crossbarry bridge at the eastern end of the ambush positions where they placed a mine on the road. A second mine was planted near Harolds Lane at the western end of the ambush area.

The remainder of the column waited until 6 a.m. in the field behind Beasleys. This long wait was spent huddled against fences without food or sleep, the men having had only one hour sleep before the alarm was raised at 2.30 a.m. It was a dry but bitterly cold night. By dawn the volunteers had moved into their appointed sections chosen the previous night. There were seven sections that stretched from Harolds Lane at the western end to the bend of the road before Crossbarry village at the eastern end of the chosen ambush position.

The Section Commanders were:

Section "A": Sean Hales

Section "B": John Lordan

Section "C": Mick Crowley

Section "D": Pete Kearney

Section "E": Denis Lordan

Section "F": Tom Kelleher

Section "G": Christy O'Connell

Circumstances had changed for the flying column. The planned ambush of five or six lorries was to become a battle for their very survival and ultimately a demoralising defeat for the British. Just after 7 a.m. Liam Deasy and Tom Barry took up position at Section E (Lordan's) already chosen as ambush H.Q. Within minutes the quiet the morning was shattered by the sound of gunfire from the north east. This was the first indication the column had of any enemy activity other than in the west from where lorries were first reported. Reports from other scouts indicated activity throughout the entire area and it became obvious that major activity by the enemy was in progress. Within minutes the sound of rifle fire and the skirl of bagpipes was heard from the direction of Harolds and Beasleys at the western end of the ambush position. The Battle of Crossbarry had begun in earnest.

From the beginning of the fighting Flor Begley, the brigade piper, played martial airs on his war pipes and continued to play while the firing lasted. Volunteers who fought at Crossbarry, spoke later of the way the piper spurred them on to greater effort. Tom Kelleher often said over the years that followed, "that man's music was more effective than twenty rifles”. The piper also had an effect on the morale of the British troops. They would have associated a piper with a battalion in their army, and consequently would have thought that there were many more volunteers present than there really were. Liam Deasy, writing some forty years later, says in his book "Towards Ireland Free" that "this was Begleys finest hour and will always be remembered as "The Piper Of Crossbarry".

Roadside memorial at Ballymurphy indicating the location where Charlie Hurley, Brigade O.C. was shot dead.

Initially the ambush did not proceed as planned. All sections were under strict orders to remain out of sight of the enemy until all of the five or six lorries expected were within the 600 yard ambush position. However, when only three of the lorries had entered the trap, one volunteer poked his rifle out of an upper window in Beasleys barn and was seen by the driver of the first lorry. He immediately stopped the lorry and shouted a warning.

John Lordan, commander of B section, realised what had happened and ordered his volunteers to open fire on the enemy. Hales' men in A section and Mick Crowley's men in C section immediately opened fire as well. Meanwhile, the men of G section opened fire on those lorries which had not yet entered the ambush position on the enemy who were moving in on foot from the western end in an attempt to outflank the column. After the fight had raged in this area for some time many of the enemy broke and ran towards the railway embankment south of the road.

Suddenly came the sound of firing from a new and unexpected point, rather close. The volunteers now realised that the enemy was now moving against them from the north, or east, or both. It became obvious that if the enemy gained the high ground on Skeheenahaine Hill (north west of the ambush site) the volunteers would be unable to withdraw to the north west which was the obvious route open to them. If the enemy were to be successful in taking the high ground at the rear of the ambush column, then the losses incurred by the volunteers in fighting their way north could be serious. This route had to be kept open. Liam ordered Spud Murphy, second in command of Crowley's section, to take the six most experienced men in the section to reinforce Kelleher's section.

As Murphy had been wounded a week before at Rosscarbery and had his right arm in a sling, he placed this section under the command of Tom Kelleher They did much to halt the enemy's attempts to surround the column. Had the attempt succeeded then the volunteers could well have been annihilated.

The British troops left the quarry road and advanced up O'Driscolls old road, to get behind the rear flank of the column. Now Kelleher was confronted by a vastly superior force. Some of the troops went around the back of O'Driscolls, making for the high ground on Skeheenahaine Hill. Kelleher knew that if the British succeeded in gaining the hill their only line of withdrawal would be sealed off. He also realised that his group of 14 men could not withstand a frontal attack from this superior force. Kelleher - the great tactician that he was, laid his own traps for the enemy. Across a stream to the left of Kellehers position were the ruins of Ballyhandle Castle in what is a large undulating field. He now dispatched two men, Dan Mehigan (Captain of the Bandon Company) and Con Lehane (Captain of the Timoleague Company) to the ruins with orders to hold their fire until the enemy, who were approaching the ruins from behind O'Driscolls farm, were well into the open field and then to shoot the officer leading the advance. While the advance guard of this detachment were moving towards the castle ruins, Kellehers section opened fire on the main body of troops who were advancing across the valley (from O'Driscolls old road) with the obvious intention of joining up again with the detachment who skirted behind the farmhouse.

Meanwhile Mehigan and Lehane in the castle ruins carried out Kelleher's orders to the letter, and allowed the advance group to come within twenty yards of their position and then opened fire. The enemy officer, a Captain Hotblack of Major Percival's infamous staff, was shot dead in front of the castle, and of the 30 N.C.O.'s and men in his platoon many were killed or wounded. The rest scattered in disarray. Kelleher's plan had worked brilliantly.

Having dispatched "Spud" Murphy and reinforcements to support Kelleher, Liam Deasy now left Crowley's Section C and proceeded to sections A & B where the fourth action had taken place and where now the men of these sections (on the orders of Tom Barry) were gathering up the arms and ammunition captured from those troops in the ambushed lorries. The ammunition was very welcome, as each volunteer had had only forty rounds each at the beginning of the action and much of this had been expended. Tom Barry ordered the bodies of the British troops, some dead in the lorries and on the road, some dead in the field south of the road, to be gathered together and placed away from the lorries, and then he ordered the lorries to be burned.

Liam Deasy informed him of the new phase of the battle (the shooting at the rear) that Barry could not have heard with the firing that had been going on around him and of the steps he (Deasy) had taken to reinforce Kelleher's position.

After quick consultation, the Column commanders decision was that the Brigade Adj should take sections A, B, C and G at all speed to Skeheenahaine Hill, a quarter of a mile to the rear of these sections, and get control of the hill before the enemy could. Meanwhile, the Column commander would go first to the relief of Kelleher, and then bring Kearney's, Lordan's and Kelleher's sections (D, E and F), out to join them on Skeheenahaine hill. The agreed signal for withdrawal was to be two blasts of his whistle.

Liam Deasy and the main body saw the lorries on fire and, with the arms collected (one Lewis gun and ten pans of ammo, rifles and ammo) they retired at the double up Harold's old road across two fields under cover of fences and took up position at Skeheenahaine minutes after leaving the ambush positions. He now surveyed the situation from the high ground and had an excellent view of the south, east and north east. They waited for the arrival of Tom Barry and the sections D, E, and F.

Now for the first time firing was heard coming from the direction of Crossbarry village almost three quarters, of a mile away. It was obvious that a third force of enemy was now advancing from the south east and were engaged by Kearney and Lordan's sections (D & E). Seconds later a fourth force (under the command of Major A.E. Percival) of 30-40 troops at the double, were observed due east towards Killeens and were advancing with intention of getting behind both Kearney's and Lordan's sections to surround them. Had they been able to cross the Crossbarry - Begley's Forge road 300 to 400 yards ahead of them, they would have succeeded and the result would have been fatal to the men of these two sections. To stop them was imperative.

Deasy ordered the 60 men now at Skeheenahaine to line the fence facing east and fire three rounds of independent fire at 1200 yards. Though the possibility of hitting any of the enemy was almost nil, they, the enemy, would know that they faced a strong force and they might be wary of continuing their action at their present speed. The effect was immediate. Not alone did they stop in their tracks, they about-faced and raced for the protection of Hartnetts yard and the surrounding fences. They did not appear for the remainder of the battle. Ten minutes later the Column commander arrived with Kellehers section and the wounded Jim Crowley.

Denis Lordan's Section E was first attacked from the Crossbarry - Dunkeareen road immediately in front of his position, and then from Crossbarry bridge and from the Kileens area. These were the enemy forces from Cork and Kinsale respectively. His position was the most exposed of the ambush positions and his men were behind a very low fence with rising ground behind them, making any withdrawal extremely hazardous over open ground. Even to gain the comparative safety of Beasley's garden, and then the previously agreed withdrawal route up Harolds old road, they would have to cover almost three hundred yards along a very low ditch. The volley from Skeheenahaine was clearly heard by the men in Section E and the enemy fire from 1 the Kileens direction ceased immediately thus giving them some relief. Nevertheless, Lordan felt it would still be extremely tricky to withdraw from their position as they were still under fire from the Dunkeereen road and Crossbarry bridge, yet to remain in this position was even more risky as Lordan realised they would be cut off by the enemy troops. He made the decision to withdraw. Two of his men, Jerh. O'Leary and Con Daly had been killed.

Peter Monahan (not his real name), a Scotsman of Irish parentage, was also fatally wounded. Monahan (his mother was from Mallow) was a deserter from the Cameron Highlanders stationed at Cobh in East Cork. He was a Sergeant in the Royal Engineers attached to the Camerons. The mine at E section failed to detonate and while checking it out was shot. He is buried in the Republican Plot at St. Patrick’s cemetery in Bandon.

The decision to withdraw having been made there was no time to lose. Now luck favoured the volunteers once more because Lordan, in the act of moving Monahans body, slipped and accidentally touched the plunger with his arm and detonated the mine on the road. The explosion took the enemy by surprise and sent a huge cloud of dust and earth into the air. Under cover of this accidental good fortune, Lordan and his men made a run for the safety of Beasley's garden and he led them up Harolds old road and up to Skeheenahaine by the route taken by the main body of Volunteers and joined them about twenty five minutes after they had arrived there.Now the full Column (minus the three dead, Peter Monahan, Jerh. O'Leary and Con Daly) was assembled at Skeheenahaine Hill. It was essential that they gain the safety of the higher ground of Raheen Hill about two miles north, the highest ground in the area.

There were quick consultations between Deasy, Barry and Kelleher. It was decided that Deasy, would take the main body of men directly, by the shortest route, to Raheen Hill and to hold it if attacked. Tom Barry and Tom Kelleher would bring the rearguard of twenty five men and four wounded, two of them seriously, by a circuitous route to the same location. In this they were successful, having met no further resistance. The Battle of Crossbarry was over.

There are a number of reasons why the British suffered their greatest defeat during the Irish War of Independence at Crossbarry,

one of the main being their failure to surround the Column completely. This was because the one hundred and twenty Auxiliaries who set out from Macroom to participate in the roundup went to Kilbarry instead of to Crossbarry. This left the North - North West segment of the encirclement uncompleted and this was the route by which the Column were able to break out. Had the Auxiliaries arrived to close that gap it is probable that the Column would have been wiped out.

Another reason was that the while the British were not aware that the volunteers were at Crossbarry the Column were made aware of the British presence in the area as early as 2.30 a.m. by the lights and noise of their lorries coming from the direction of Bandon. This advantage of surprise had a telling effect on the battle that followed.

The high morale of the IRA volunteers was another major contribution to the outcome. The unit had a strong belief in their cause, with a calm confidence in their leaders and in each other. But the main reason was leadership. On the day Liam Deasy, Tom Barry and Section Commanders Tom Hales, John Lordan, Mick Crowley, Pete Kearney, Denis Lordan, Tom Kelleher and Christy O'Connell provided the essential leadership required.

The official account of British casualties was thirty nine soldiers killed, including five officers, and forty seven wounded although some subsequent reports stated that British losses were far greater.

It is interesting to note that three of the British troops at Crossbarry were awarded medals for bravery shown on that day, they were: Acting Sergeant B. Loftus, 1155 (MT) Coy., R.A.S.C. His citation reads, "This N.C.O. showed great gallantry and initiative in leading men during an ambush on March 19th, 1921. He also made repeated attempts, under heavy fire to rescue a wounded officer lying in an exposed position." Acting Sergeant A. Mepham, 1155 (MT) Coy., R.A.S.C. His citation reads, "During an ambush on a convoy of several lorries, the Crown Forces sustained heavy casualties and were forced to leave their lorries and retire on a small farm. Sergeant Mepham seeing the officer in charge of the convoy and several others lying wounded in exposed positions, made his way back to the lorries and drove off one in which he took all the wounded to a place of safety".

Sergeant M.M. Poole, 1st Essex Regiment, His citation reads, "Sergeant Poole displayed gallantry in leading a party of young soldiers in action on 19th March, 1921. He also made repeated attempts to bring in a wounded officer lying in an exposed position, under heavy fire".

Their crushing defeat at Battle of Crossbarry, effectively broke the resolve of the British Government and Prime Minister Lloyd George gradually came to the conclusion that the Irish conflict could not be resolved by by force alone. They now sued for peace and finally, on July 11th. 1921, a truce was declared.