Major Defeat For Auxiliaries at Kilmichael

The monument at Kilmichael where the West Cork Flying Column led by Tom Barry won a major victory.

One hundred and fifty members of the new force of Auxiliaries arrived in Macroom in August 1920, and took over Macroom Castle as their barracks. They were recruited from ex-British officers who had held commissioned rank and had active service during the 1914-18 war. Highly paid, their war ranks had ranged from Lieutenant to Brigadier-General. Each carried a rifle, two revolvers, one strapped to each thigh, and two Mills bombs hung at the waist from their Sam Browne belts.

From the time of their arrival in Macroom they raided constantly, travelling to places like Coppeen, Castletown-Kenneigh, Dunmanway and even south of the Bandon river. Their modus operandi was simple. Fast lorries would come roaring into a village, the occupants would jump out, firing their guns, ordering all the inhabitants out of their houses. No exceptions were allowed. Men and women, young and old, the sick and disabled, were lined up against walls with their hands up, questioned and searched. For hours the little community would be held prisoner with many suffering at the butt ends of revolvers or rifles, The raiders commandeered food and drink and rarely returned sober to their barracks. Observing some man working at his bog or small field a few hundred yards from the road, four or five would take aim, not to hit him, but to spatter the earth or bog round him. The man would run with bullets clipping the sods around him. He would stumble and fall, rise again and continue to run for safety. But sometimes he would not rise, as an Auxiliary bullet was sent through him. The Auxiliaries had been allowed to roam through the countryside for four or five months, terrorising and killing and not a single shot had been fired at them up to that point. They were invincible in the minds of many people. They had to be stopped.

On November 21st. a column of thirty-six riflemen were mobilised at Clogher, north-west of Dunmanway, for a week's training, in advance of an attack on these Auxiliaries. At 2 a.m. on the following Sunday, the flying column of thirty-six riflemen fell in at Ahilina. Each man was armed with a rifle and thirty-five rounds. A few had revolvers, and the commander had also two Mills bombs, which had been captured in a previous ambush at Toureen. At 3 a.m. the men were told for the first time they were moving in to attack the Auxiliaries between Macroom and Dunmanway.

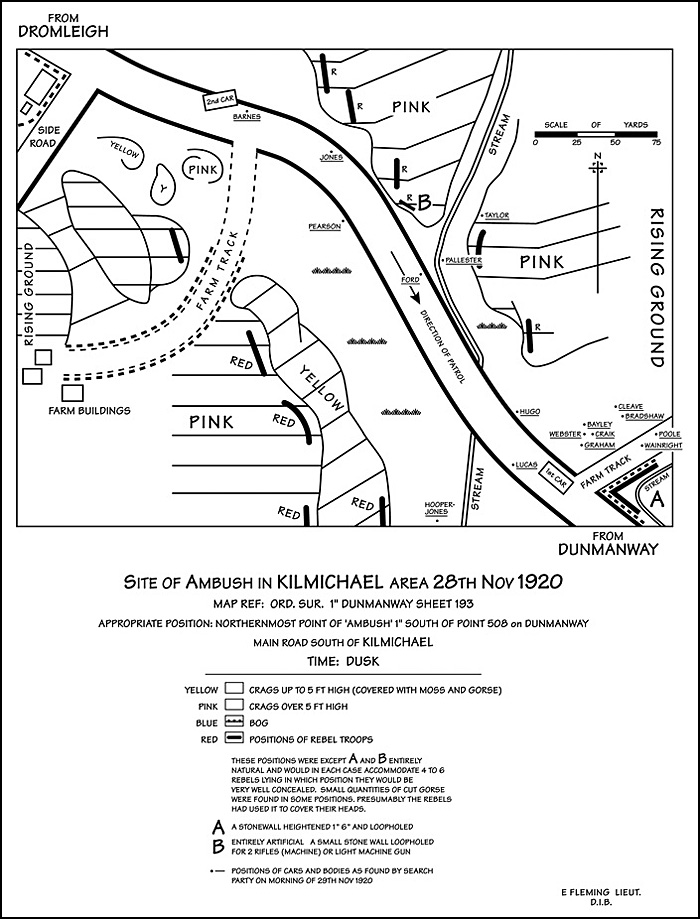

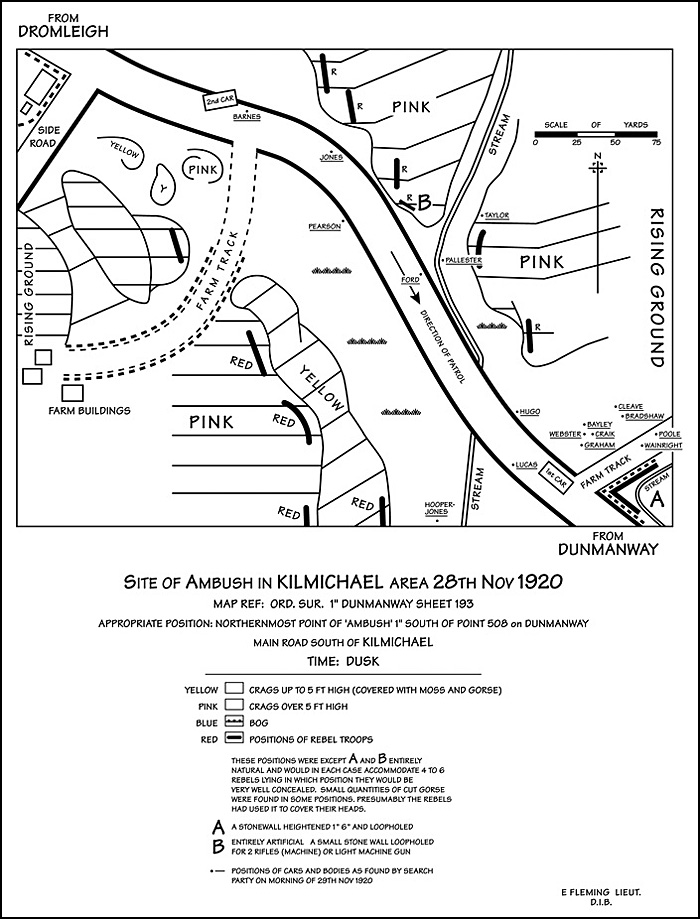

The Column started its march in lashing, rain and reached the ambush position at 8.15 at dawn. The ambush area was in the centre of a bleak and barren countryside, a bog land interspersed with heather and rocks. It was bad terrain for an ambushing unit because of the lack of roadside ditches and cover, but the Column had to attack in this area as there was no certainty of meeting them anywhere except on this road between Kilmichael Cross and Gleann Cross which they never once failed to travel.

A view of the ambush scene looking southwards. The first lorry was halted by a Mills bomb thrown by Comandant Tom Barry who stepped from behind the low wall at the marked area. He, along with John 'Flyer' Nyhan, Jim 'Spud' Murphy and Mick O'Herlihy directed a hail of gunfire at the Auxiliaries.

The point of this road chosen for the attack was one and a half miles south of Kilmichael. Here the north-south road turns west-east for 150 yards and then resumes its north-south direction. There were no ditches on either side of the road but a number of scattered rocky eminences of varying sizes. No house was visible except one, 150 yards south of the road at the western entrance to the position.

Before being posted, the whole Column was paraded and informed of the plan of attack. They were also told that the positions they were about to occupy allowed for no retreat and would be a fight to the end, All the positions were pointed out to the whole Column, so that each man knew where his comrades were and what was expected of each group.

Details of the plan were as follows -

* The command post was situated at the extreme end of the

ambuscade, and faced the oncoming lorries. It was a small narrow wall

of bare stones, so loosely built that there were many transparent spaces.

It jutted out on to the northern side of the road, a good enfilading

position but affording little cover. Behind this little stone wall were also

three picked fighters, John (" Flyer ") Nyhan, Clonakilty; Jim (" Spud")

Murphy, also of Clonakilty, and Mick O'Herlihy of Union Hall. The attack

was to be opened from here, and under no circumstances whatever was

any man to allow himself to be seen until the Commander had started

the attack.

* No. 1 section of ten riflemen was placed on the back slope of a

large heather-covered rock, ten feet high, about ten yards from the

Command Post. This rock was a few yards from the northern edge of

the road. By moving up on the crest of the rock as soon as the action

commenced, the Section would have a good field of fire.

* No. 2 section of ten riflemen occupied a rocky eminence at the

western entrance to the ambush position on the northern side of the

road, and about one hundred and fifty yards from No. 1 section. Because

of its actual position at the entrance, provision had to be made so that

some men of this Section could fire on the second lorry, if it had not

come round the bend when the first shots were fired at the leading lorry.

Seven men were placed so that they could fire if the lorry had come

round the bend and three if it had not yet reached it. Michael McCarthy

was placed in charge of this Section.

* No. 3 Section was divided. Stephen O'Neill, the section

commander, and six riflemen occupied a chain of rocks about fifty yards

south of the road. Their primary task was to prevent the Auxiliaries from

obtaining fighting positions south of the road. If the Auxiliaries succeeded

in doing this, it would be extremely difficult to dislodge them, but

O'Neill and his men would prevent such a possibility. This Section was

warned of the great danger of their cross-fire hitting their comrades north

of the road and ordered to take the utmost care. The remaining six riflemen

of No. 3 section had to be used as an insurance group. There was no

guarantee the enemy would not include three, four or more lorries. Some

riflemen, no matter how few, had to be ready to attack any lorries other

than the first two. These men were placed sixty yards north of the ambush

position, about twenty yards from the roadside. From here they could fire

on a stretch of two hundred and fifty yards of the approach road.

* Two unarmed scouts were posted one hundred and fifty and two hundred

yards north of No. 2 section, from where they were in a position to signal

the enemy approach when nearly a mile away. A third unarmed scout was

a few hundred yards south of the command post to prevent surprise from

the Dunmanway direction.

All the positions were occupied at 9 a.m. The Column had no food. There was only one house nearby and although these decent people sent down all their own food and a large bucket of tea, there was not enough for all. The men's clothes had been drenched by the previous night's rain and now it was intensely cold as they lay on the sodden heather. The hours passed slowly. Towards evening the gloom deepened over the bleak Kilmichael countryside. Then at last at 4.5 p.m. a scout signalled the enemy's approach.

A view of the northern aspect of the site taken a few years after the confrontation. The Crossley tenders swept around the bend from the left and into the ambush.

The first lorry came round the bend into the ambush position at a fairly fast speed. Then column commander Tom Barry, dressed in a military style uniform stepped onto the road with his hand up. The driver of the lorry, seeing the uniformed figure, gradually slowed down. When it was thirty-five yards from the volunteers command post a Mills bomb was thrown by Barry and simultaneously a whistle blew signalling the beginning of the assault. The bomb sailed through the air to land in the driver's seat of the uncovered lorry. As it exploded the rifle shots rang out. The lorry, its driver dead, moved forward until it stopped a few yards from the small stone wall in front of the command post. While some of the Auxiliaries were firing from the lorry, others were on the road and the fight became a hand-to-hand one. Revolvers were used at point blank range, and at times, rifle butts replaced rifle shots. The Auxiliaries were cursing and yelling as they fought, but the I.R.A. coldly outfought them. In less than five minutes all nine Auxiliaries were dead or dying sprawled around the road, except the driver and another who were lying lifeless in the front of the lorry.

The second lorry had stopped and was coming under fire from No. 2 section. The Auxiliaries were lying in small groups on the road returning fire. Three riflemen from the command post, Murphy, Nyhan and O'Herlihy, moved in to attack the second party from the rear when they heard the Auxiliaries shout "We surrender". Some of them were seen to throw away their rifles. Firing stopped and three of the volunteers in No. 2 Section stood up. The Auxiliaries began firing again with revolvers and two of the three men fell.

When he saw this Tom Barry gave the order, "Rapid fire and do not stop until I tell you". The Auxiliaries once again shouted "We surrender" but on this occasion the order was given "Keep firing on them. Keep firing, No. 2 Section. Everybody keep firing on them until the Cease Fire". The small I.R.A. group on the road was now standing up, firing as they advanced to within ten yards of the Auxiliaries. When the cease fire order was finally given there was an uncanny silence as the sound of the last shot died away. Sixteen Auxiliaries were dead and one seriously wounded. Volunteers Michael McCarthy, Dunmanway and Jim Sullivan, Rossmore also lay dead, and Pat Deasy was dying.

The lorries were set ablaze. Like two huge torches, they lit up the countryside and the corpse-strewn road. Some of the volunteers showed the strain of the ordeal through which they had passed, and a few appeared on the point of collapse because of shock. The entire column was ordered to drill and march and for five minutes the eerie drill continued. They then halted in front of the rock where Michael McCarthy and Jim O'Sullivan lay, where they presented arms as a tribute to the dead volunteers. Just thirty minutes after the opening of the ambush the column moved away to the south, intending to cross the Bandon river upstream from the British held Manch Bridge. Eighteen men carried the captured enemy rifles slung across their backs. It started to rain again and the men were soon drenched. The rain continued as the I.R.A. marched through Shanacashel, Coolnagow, Balteenbrack and arrived in the vicinity of dangerous Manch Bridge. The Bandon River was crossed without incident and Granure, eleven miles south of Kilmichael, was reached by 11 p.m.

The following day the volunteers remained at the cottage where they had billeted while reports of intense enemy activity came in. Large forces of British were gathering at Dunmanway, Ballineen, Bandon, Crookstown and Macroom before converging on Kilmichael. One unit of 250 steel-helmeted soldiers moving on to Dunmanway about noon, passed two hundred yards from the cottage. Other enemy units were moving at the same time a few miles away on to Manch Bridge. No risks were taken by them as it was nearly 1 p.m. when all their forces reached Kilmichael. The British were aware at 6 p.m. on the Sunday evening that the Auxiliaries had been ambushed, yet it was late evening on the following day before they ventured to the scene of the fight. British forces converging on Kilmichael, carried out large scale reprisals around the ambush area. Shops and homes and farms were destroyed at Kilmichael, Johnstown, Inchigeela and other areas.

As already stated, the engagement at Kilmichael was the first between the IRA and the previously invincible Auxilaries and has long been recognised as being one of the most important battles of the Anglo-Irish War. Shaken to the core, the British establishment could not comprehend how 18 battle-hardened officers fell in combat against what they previously dismissed as little more than rabble. The British government were running out of options and in December 1920 martial law was declared in the four Munster counties of Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Tipperary.

The monument at Castletown-Kenneigh graveyard where Volunteers Michael McCarthy, Jim Sullivan and Pat Deasy are buried.

This dramatic picture, taken at Kilmichael in the days following the ambush, shows one of the burnt out Crossley tenders.