The Killing of Lord Mayor Tomas MacCurtain

Tomás MacCurtain pictured with his wife and young family in March, 1920, just a few days before his murder.

Tomás MacCurtain was shot dead at his home at Thomas Davis Street, Blackpool between 12.10 a.m. and 1.15 a.m. on Saturday, March 20, 1920. It was the morning of his thirty-sixth birthday. The fatal revolver shots were fired by two men with blackened faces who had rushed upstairs and called him out of bed after his wife had opened the door to their knocks and threats. Companions of the murderers held her at the door while the crime was being committed. The inquest verdict found that all those engaged were members of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

The circumstances of the murder were the subject of a historic inquest, conducted by Coroner James J. McCabe, in which ninety-seven witnesses were examined, sixty-four of them being police, thirty-one civilians, and two military. The inquest was opened on March 20 and concluded on April 17 with the following unanimous verdict:

We find that the late Alderman MacCurtain, Lord Mayor of Cork, died from shock and hemorrhage caused by bullet wounds, and that he was willfully murdered under circumstances of the most callous brutality, and that the murder was organised and carried out by the Royal Irish Constabulary, officially directed by the British Government, and we return a verdict of willful murder against David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of England; Lord French, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland; Ian McPherson, late Chief Secretary of Ireland; Acting Inspector General Smith, of the Royal Irish Constabulary; Divisional Inspector Clayton of the Royal Irish Constabulary; District Inspector Swanzy and some unknown members of the Royal Irish Constabulary. We strongly condemn the system at present in vogue of carrying out raids at unreasonable hours. We tender to Mrs. MacCurtain and family our sincerest sympathy. We extend to the citizens of Cork our sympathy in the loss they have sustained by the death of one so eminently capable of directing their civic administration.

It was the first, though not the last, premeditated murder of a Republican public representative holding a post of high honour, and, even for the abnormal conditions of the time, the circumstances surrounding it were unusual and shocking. The police evidence at the inquest revealed that the Lord Mayor was to have been arrested on the night he was murdered.

County Inspector Maloney said that on March 19 he 'received certain verbal orders from the Military Authorities—namely to detail three men to meet a military lorry at 2 a.m. on the following morning'; and on being asked for what purpose, he replied: 'To arrest the Lord Mayor of Cork'. He 'passed the order on to the District Inspector Cork (North) whose district it was, District Inspector Swanzy'.

District Inspector Swanzy swore that he was told in Union Quay barracks 'about mid-day on March 19' by Mr. Clayton, the County Inspector who had just been appointed Divisional Commissioner, and Mr. Maloney, the County Inspector who had 'arrived in Cork only at twelve noon on Thursday and knew nothing of local conditions' that the Lord Mayor was to be arrested. 'He was ordered to detail some policemen to point out the Lord Mayor to the military.' Later in his evidence he said: 'I was not ordered to arrest the Lord Mayor, but I was ordered to detail police to indicate the house of the Lord Mayor to a military party.' He 'told the Head Constable to detail two of the night men to carry out the military order'.

That seems sufficiently clear and definite, but for some reason, not apparent from the evidence, there was a further consultation between police and military on the matter. Swanzy says': 'At five o'clock on the afternoon of March 19, at King Street Barracks', a military officer showed him a document 'directing' the arrest of the Lord Mayor, but that the military officer took the document away. 'The hour of arrest was arranged at five o'clock on the afternoon of March 19 when the military officer called. The hour arranged was 2 a.m. on March 20.'

Head Constable Cahill, King Street Barracks, in his evidence said that 'he got orders from the competent Military Authority on March 19, relating to the late Lord Mayor, and he communicated these orders to Sergeant Beatty at about 11.10 p.m. He detailed Sergeant Beatty and three constables to accompany a party of military to the residence of the late Lord Mayor. The military party was to call at King Street.' Under cross-examination Head Constable Cahill said in regard to the time at which he got the order: 'I couldn't fix the time, but it was in the afternoon, probably three or four o'clock. A type-written communication was shown to me by the District Inspector in his office. . . . Amongst other things it contained a reference to the Lord Mayor, and the Lord Mayor was the only person we were concerned with. ... I am not sure whether it was four or five persons were referred to.'

The obvious discrepancies between the evidence of Swanzy and Cahill are important in so far as they reflect the unreliability of the police evidence as a whole. Both Maloney and Swanzy appear to create the impression that there never was a police document in relation to the proposed arrest; there was a verbal request at Union Quay for police to accompany a military party, and a document at King Street, the purpose of which is by no means clear, but at least it was a military document, brought and taken away by a military officer 'at five o'clock' after having been shown to Swanzy. This evidence tends to dissociate the police from any responsibility for, or approval of, the proposed arrest.

Against it there is the evidence of Head Constable Cahill who was shown 'a type-written document' by Swanzy in his office in King Street 'probably between three and four o'clock'. It related to others besides the Lord Mayor; 'four or five persons were referred to but the Lord Mayor was the only person we were concerned with'. That might mean that the others referred to were not in Head Constable Cahill's district. But if that is so, why was it that no other arrests were carried out on that night?

The evidence of Sergeant Beatty of St. Luke’s station, who was on beat duty in King Street, is to the effect that the military lorry-arrived at King Street Barracks about 2.15 a.m. or 2.20 am., that he, with Constables Sullivan, Murphy and Walsh, went with the military party to the Lord Mayor's house and found he had been shot dead.

Major General Strickland, commanding the British 6th Division with headquarters in Cork, said in evidence that 'the authority for the order for the arrest of the Lord Mayor came from the Government. It came to him from the Commander-in-Chief in Ireland. The document contained authority for arrest and search.' The order 'was received about mid-day on March 19'. When asked if the order contained any other names besides that of the Lord Mayor, General Strickland replied: 'I can't answer that question'.

Lieutenant D. F. Cooke stated that on March 19 he was detailed to take charge of a party of twenty men to report at King Street Police Barracks at 2 a.m. the following morning to carry out arrests. He reported at King Street and was joined there by a Sergeant and three Constables. He learned then for the first time who was to be arrested. He got the name of Thomas MacCurtain, 40 Thomas Davis Street. He went to the Lord Mayor's house, and was there informed that he had been shot dead. He considered that it was his duty to search the house, and he did so, including the bed on which the remains of the Lord Mayor were lying. The police refused to enter the house with him when they heard the Lord Mayor was dead.

It may be accepted on this evidence that there was an order from British Headquarters in Dublin for the arrest of the Lord Mayor, that it was transmitted to General Strickland, passed by his officers to the County Inspector at Union Quay and a request made for police to accompany the military party in making the arrest. Both Lieutenant Cook and General Strickland in their evidence, and the latter in a letter to the Bishop of Cork, published in the Cork Examiner of March 23, stretched the interpretation of the order to include a search of the Lord Mayor's house. The purpose of; that interpretation was an attempted justification of the action of the military party in searching the house after the murder.

The rime at which the arrest was to be carried out was 'arranged at five o'clock on the afternoon of March 19, when the military officer called' at King Street Police Barracks. 'The hour arranged was 2 a.m. on March 20.' (Swanzy's evidence). It is clear from this that the actual arrangements for arrest were left in the hands of District Inspector Swanzy.

The police were well aware that the Lord Mayor was at this time attending assiduously to the duties of his public office, and that he was to be found at his desk in the City Hall at any time except when engaged at some public function, at any of which he could have been located just as easily. The police were also well aware of his domestic circumstances and of his young family. The question arises as to why it should have been thought necessary to invade his private house, to invade it with all the terroristic display of a mixed armed force of police and military with fixed bayonets, why it should have been thought necessary to subject women and young children to this brutal ordeal at two o'clock in the morning. Was it just callous disregard of humanitarian considerations, mere revengeful vindictive-ness, or did it have a more sinister purpose? Was the murder of the Lord Mayor planned for that night, and would his earlier arrest by the military have deprived the murderers of their intended victim?

The theory that the murder of the Lord Mayor was a reprisal for the shooting of Constable Murtagh at Pope's Quay about 11 p.m. on the night of March 19 presupposes that the crime was planned and carried out within two hours—between 11.15 p.m. on the March 19 and 1.10 a.m. on March 20. If the whole party engaged came from one barracks that may be possible, but the evidence, as will be shown, indicated that a larger number participated than the admitted available strength of the King Street force.

Head Constable Cahill, in charge of King Street Barracks, said that on the night of March 19, 'twenty-four men all told were stationed there . . . one Head Constable, seven sergeants and sixteen constables'. All these twenty-four men gave evidence at the inquest. That evidence shows that one sergeant was absent through illness, one sergeant and three constables were in lodgings outside the barracks, and three constables "were on beat duty in King Street. Therefore the total number of police in the barracks, if their evidence is accepted, was sixteen, including the Head Constable and the barrack orderly. They did not all leave the barracks; there is evidence that the group returning were admitted by someone inside about 1.40 a.m. Other evidence is to the effect that this group numbered about eight.

It is quite certain, as will be shown later, that a larger number than eight took part in the crime, and it is a reasonable inference that some of them came from some place other than King Street. The question therefore arises, whether the assembly of the larger number concerned, the provision of clothing for disguise, the blackening of faces and the allocation of positions and duties, (all evidence of careful preparation) could have been decided upon, organised and carried into effect between 11.15 p.m. and 12.45 a.m.—the time at which the group from King Street passed there on the way to the Lord Mayor's house. Could all the indications of premeditated caution and secrecy which surround the crime, and which, but for the accident of a few witnesses, might have cloaked its perpetrators completely, have been thought out and put into operation in an hour and a half? If not, then the shooting of Constable Murtagh was not a factor in the event which followed it.

A direct link to those responsible for the crime was provided by the finding of a button from an RIC tunic at the door of the MacCurtain house on the morning following the murder. It was found by the local postman, Mick Goggin, seen here on a visit to the Kilmichael ambush site in West Cork some years after the event. Pictured are from left are Bill Goggin (son), Mick Goggin and friend Gerry Healy, all of Kilbarry, Old Mallow Road, Cork city.

Tomas was at his desk in the City Hall on the afternoon of Friday, March 19. Con Harrington, the Town Clerk, was with him when Alderman Tadhg Barry came in and said that he had heard if another policeman was shot in Cork Tomas would be shot in reprisal. The only comment made by the Lord Mayor was: 'That's interesting'. He went on with his work, as was his way. He had before then received anonymous letters threatening him with death. He disregarded them entirely. Since his election to the office of Lord Mayor he felt that his public position demanded the open performance of his municipal functions, and that whatever the dangers of arrest or assassination might be he should not go into hiding or attempt to evade them.

One of his last official acts on the night of his death was to call to Brigade Headquarters at the shop of Sheila and Nora Wallace at St. Augustine Street for the purpose of discussing some matters relating to the brigade with one of his officers.

Tadhg Barry left Wallace's with him, and about ten p.m., with his brother-in-law, James Walsh, he was on his way home to Thomas Davis Street. Somewhere on the way he was told of the shooting of Constable Murtagh at Pope's Quay. He called into the Watercourse Road Sinn Fein Club, spoke to Con O'Connell, Peadar McCann and some others who were there and advised them to go to their homes. Peadar McCann walked with him to his home. On reaching there he phoned to the North Infirmary and made enquiries about Constable Murtagh, at the same time offering his sympathy. He retired to bed about midnight. In the house, in addition to the Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress, were their five children, the youngest being ten months, Mrs. MacCurtain's brother and three sisters, two nieces and a nephew, and Mrs. MacCurtain's mother, who was an invalid.

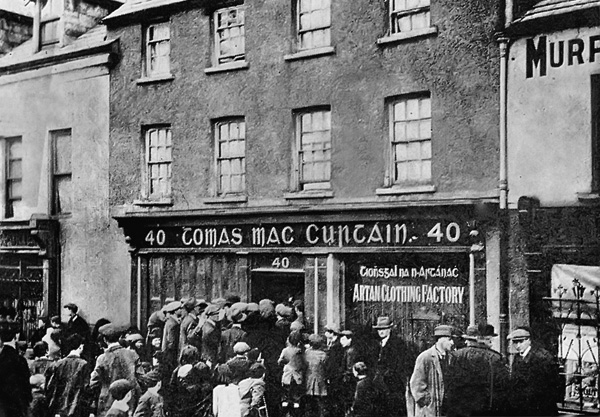

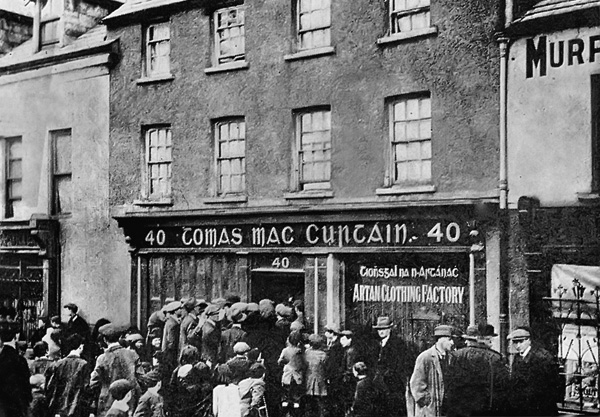

Shocked citizens reading the death notice on the door of the MacCurtain home on the morning of the murder.

At about 1.10 a.m. Mrs. MacCurtain heard knocking at the street door and some time afterwards a noise as if the door was being broken in. She looked out the window of her bedroom and asked who was there. The answer was: 'Come down'. Tomas got up and said: 'Lizzie, I'll go down myself.' Mrs. MacCurtain, however, took a lighted candle and went downstairs. She describes what happened:

When I opened the door a man rushed in with a black face and eyes shining like a demon. One man outside the door then asked, where Curtain was, and I said he was upstairs. Six men rushed in the hall, four tall men and two small men; the two small men were about my own height and carried rifles, which they held against their sides. I don't know what the tall men had, they may have had rifles but I didn't sec them. . . . One gave orders to hold 'that one', meaning me, and the second tall man turned round and shoved me towards the door, but didn't say a word. He wore a big overcoat and cap. His face was blackened and he turned it from me immediately. He had fair foxy hair. He was a well built man.

Mrs. MacCurtain described how, while she was held at the door, the men rushed past her up the stairs, a narrow stairs with a difficult turn at the top. 'They seemed to know the house better than I did myself.' Almost immediately, before she thought they could have gone two steps up the stairs she heard the shots which killed her husband. When the men came downstairs they pushed her before them into the street, where she began to cry for help and call for someone to go for a priest. At the same time her brother was calling out from a top window, and she heard the order given to the group of ten to fifteen men outside the house: 'Fire again'. Some of the men faced the door and fired up towards the windows. Marks made by these bullets were found subsequently.

What occurred upstairs while Mrs. MacCurtain was held at the door is described by her brother James Walsh, and her sisters Susie and Annie Walsh. Susie was awakened by what seemed at first gentle knocking, and then a sound as if someone was trying to break in the street door. She called her brother who was in an adjoining room. He relates that he partly dressed, took a lighted candle and went down from the top landing in which his bedroom was to that below. 'I went out on the landing and as I got there I heard a voice saying: "Come out, Curtain". This demand was repeated as I was going round the bend of the stairs about three steps from the top. I saw two tall men, one had a light overcoat. Their backs were turned to me and they were facing the Lord Mayor's room. As I got there the Lord Mayor was at the door. I saw the man on the right, who was in a light coat and wearing a brownish cap, let go, and two shots were fired. He fired a revolver. I don't know what the man on the left had in his hand. I only got a glimpse of it. I quenched the candle and dropped on the stairs. When I was lying down I heard a third shot.' When he went to the window and called for help he was fired on from outside the house.

Susie Walsh described how, after calling her brother, she rushed downstairs and saw the two men outside the Lord Mayor's door. 'One wore a light coat and cap and had his face blackened.' The baby in the Lord Mayor's room was crying, and she said to the men: 'Please let me take the baby'. The reply was 'Get back out of that'. She ran to the bathroom and while there heard the order: 'Conic out, Curtain', repeated twice. Then she heard the shots. She came out of the bathroom to find the men gone and her brother-in-law lying outside his bedroom door moaning heavily. Annie was coming down the stairs with a Crucifix and holy water. They both knelt down and prayed, Annie holding her arm under Tomas' head. He was bleeding from around the region of the heart.

Annie describes how they remained praying until the priest came in response to Mrs. MacCurtain's telephone call. 'I called on the Sacred Heart to spare him, at least until the priest would come, and shortly after some one said: "The priest is coming". When the priest came I went away for a few minutes, but came back then to sec him die. His last words were: "Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit".'

When the alarm was raised Miss Peg Duggan and her sister Anne, who lived close by, ran to the North Cathedral and came back with Rev. Fr. Burts, C.C., who administered the Last Sacraments.