By Joseph Okumu

Martyrdom does not happen by chance. The events of all martyrdom's

are always dressed up in many other events. That of the martyrs of Paimol

Daudi

Okelo and Jildo

Irwa had a number of other historic events.

Firstly, the well remembered slave trade carried out by some

Arabic-speaking traders from Sudan named, by the Acholi of the time,

munu Kutoria and subsequently munu Jadiya who had been official representatives

of the Egyptian administrators on the upper Nile until 1888.

Secondly, the new administrative policy to supplant acholi traditional

and legitimate chiefs by the agents of British Administration,-munu

Ingereza.

Thirdly the Spanish fever which broke throughout Acholi land.

Fourthly the venereal disease, which became known as nyac abac,

believed to have been spread by the slave traders who often raped beautiful

looking Acholi women and fifthly the advent of the new religion propagated

by yet another group of white people, munu karatoum. These were Italian

Catholic missionaries of based in Verona, Italy.

All these were new events which threatened the traditional Acholi

integrity. The Acholi people resented and sought ways to put an end

to them all. "Due primarily to British pressure on the Egyptian

government to halt slave trading by its subject on the upper Nile, the

Kutoria period was brought forcibly to a close in 1872 and, in 1888,

at the hands of a multi-polity Acholi force the Jadiya were defeated

and then finally withdrew from Acholi land" (Ronald R. Atkinson,

994: 268).

In 1916 part of Acholi's chiefdom of Agoro, the Logot, killed

a certain Musa, an agent of the British or munu ingereza. Another chiefdom,

Paimol, rebelled against Amet imposed on them by the same munu ingereza.

It was the responsibility of the Acholi witches, ajwaka (sing.), ajwakki

(plur.) to find remedy to Spanish fever and the nyac abac diseases.

Where there was need, the Acholi did not hesitate to consult

and make alliance with other forces to defeat a stronger enemy of their

traditional integrity. In the case of the martyrdom of Daudi Okelo and

Jildo Irwa, deposed chief, Lakidi of Paimol, consulted with and made

alliance with some rebels, the abac and some karimojong in the jungle.

Eye witnesses Fiberto and Daniele reported how the adwi planned

to kill the catechists. Another witness Gabriele Aloo assured that they

were dependable witnesses (Raccolta Albertini 1952-1953: 124-129). Over

seventy five witnesses of the martyrdom of Daudi

Okelo and Jildo

Irwa narrated the complex story of a simple act of fidelity which

has become a life inspiring value of all cultures and times.

1. Early missionary

expeditions

In the 19th and 20th century, on many European journals, much

news had already circulated on Uganda's central and eastern districts

and two such information's were supposedly accurate and at once challenging.

One such news had been reported by Sir Samuel Baker of slave trade he

had seen during his sourjourn in Acholi land as far beyond Masindi as

Pabo, Patiko and Padibe in 1863 and 1865. But little was really known

and said about the Uganda north of Masindi to the border with Southern

Sudan.

Indeed the Catholic missionaries had not been slow in taking

the challenge of moving into all this and other areas of Africa. In

1845 the first missionaries, the Holy Ghost Fathers, started evangelisation

on the Western coast of the African continent. In 1859, after numerous

and often unhappy attempts, the Fathers of the African Mission of Lyons

were able to establish themselves in Dahomey.

On the Eastern coast the work of evangelisation began around

1860. In 1874 the Missionaries for Africa (White

Fathers), founded by Cardinal Lavigerie, started moving towards

the area of the Great Lakes. On 17th February 1879 ten Missionaries

for Africa, led by Fr. Lourdel, sailed from Marseilles and, starting

from the coast at Mombasa, reached Uganda around the area that is now

known as Entebbe. The farthest they could move northward of the country,

though, was Masindi.

Besides the way from the coast, there was another possibility

of entering Uganda and this was from the north, through Sudan. This

was the path taken by the Comboni Missionaries, founded by Blessed

Daniel Comboni. From Europe, they would sail to Egypt and then on

the river Nile or cross the desert by camel all the way to Khartoum.

From there onwards, the journey was on foot or, later, by steam boat,

but only as far as the Nile cataracts.

The Comboni

missionaries spread the Gospel in the vast and little known areas

of Southern Sudan, arriving eventually in North Uganda. Driven by their

founder's cry "Africa or death" and by his charisma to evangelise

the "poorest and most abandoned", they faced enormous challenges

and sacrifices with determination and enthusiasm, overcoming obstacles

and hardships that many a times seemed insurmountable. The area in the

north of Uganda, bordering with Southern Sudan, is where the martyrdom

of Daudi

and Jildo

took place.

2. The villages of the

two martyrs in the grip of interested groups (1848-1888)

From the southern end of Uganda, Sir Samuel Baker ventured into

the interior reaching the Acholi land at Palaro, a slave market near

Patiko, also market place of traders in white and black ivory. But to

put it in colonial terms of the time, these areas were "marginal

and inferior in many ways". During the period 1863-1865, Baker

stayed among the Acholi at what later was called Fort Patiko and made

notes on the people and the land.

Then Baker was named by the Egyptian government to lead its forces

against both the slave traders, whom their Acholi victims referred to

as munu kutoria, and the Mhadi rebels that were still rustling the land

unabated. The kutoria were defeated in 1872. England had at long last

decided to do a little more than just look after the Uganda protectorate,

which by now also included the Acholi land, and began to lay claims

against the Belgians' colonial greed for what was called the Lado enclave,

northwest of present Uganda.

The Acholi people lived in fear of long droughts, wild animals,

slave traders and cattle rustlers from neighboring drier lands. Unfortunately

the British administrator, Munu ingereza in the local language, added

to their plight in an effort to bring them (the heathen, as they were

called) into the empire system by employing non-Acholi agents, irrespective

of their reputation. Indeed the neighboring Banyoro, referred to by

the Acholi as Luduni, and remnants of the slave traders, the feared

Munu Jadiya, were readily available for such a job.

Because of their centralised-polity, the Banyoro were held in

higher respect by the Crown than the heathen or pagan Acholi, because

the Banyoro had one king (a centralised social structure), while the

Acholi had many kings. The Missionaries of Africa in their evangelising

drive had reached the Banyoro and made numerous converts among them,

but did not enter Acholi land. "In 1888, defeated at the hands

of a multi-Acholi forces, the munu jadiya finally withdrew from Acholi

land". The Acholi, though, always kept a careful watch on the various

groups that showed interest in their territory.

Bending the "heathen"

Acholi to come part of the empire (1894-1916)

In 1894 a final treaty was signed by England and other European

powers to safeguard the whole of the Uganda protectorate, including

the Lado conclave. The Acholi land, though, where raids, inter tribal

feuds, famine and disease continued unabated, was still considered as

marginal and inferior. In 1902, however, Acholi land was declared as

one of the three districts of the Uganda protectorate, but, even so,

things did not improve much.

One of the tasks of the administrators of the Uganda protectorate

was to collect an "annual hut tax" from every adult male.

Since the people had no money to pay this tax, the administrators in

exchange introduced a kind of forced labour where the men were made

to construct roads and administrative buildings. It was a way to completely

subjugate the new district of the Nile province. Discreetly also the

slave trade continued, as the Comboni missionary, Mgr. Antonio Vignato,

Prefect Apostolic of the Equatorial Nile, would later confirm in his

first official correspondence with Propaganda Fide in 1923.

The administrators of the Protectorate (F.K. Girling 1960, 109-110)

started a long process of what they considered civilising the Acholi

social structure by deposing their traditionally anointed chiefs

and rulers. The great Acholi Payira sub-clan, ruled by rwot Awic, was

the first to be targeted. Between 1911 and 1912, on the order of Munu

ingereza, the indigenous chief was deposed and replaced with Yonna Odida,

believed to be more subservient to the government.

In 1917 chief Lakidi of Paimol was also deposed and replaced

by Amet, also reputed to be submissive to the government. Similar changes

were made among lower ranks of the chiefdom. In Padibe a government

administrator imposed a certain Musa, a Muslim, who in 1916 was killed

by the Logot. In Paimol, the sub chief Ogal, the one who welcomed the

two martyred catechists, was replaced by a certain Bongi. Most of the

government administrators had been assisted in carrying out their duties

by the Banyoro and Baganda.

By the time the Protestant and the Comboni missionaries arrived

in Acholi land, there were many educated Banyoro

and Baganda in the area. The Protestant missionaries made great use

of their skills to translate books. The Comboni missionaries, instead,

did so to a much lesser extent.

3. The arrival of the

Comboni Missionaries.

The Redemptor

steamboat, with Comboni Missionaries on board, set off on 30th December

1909 from the small port of Khartoum in Northern Sudan. Acholi land

had officially been recognised by the government open to Catholic missionaries

since 1902, when there was an historical policy change.

Very Rev. Fr. Federico Vianello, the Superior General of Daniel

Comboni's missionaries, Mgr. Franz Xavier Geyer, Vicar Apostolic

of the Central African Mission, and his secretary Brother Cagol might

have looked like the happiest men on earth as on board of the Redemptor

were beginning their journey towards the north of Uganda.

The Comboni missionary Fr. Albino Colombaroli, then in Wau, the

capital of the province of Bahr-el-Ghazal, received an urgent telegram

to leave for Shambe, by way of Tonje-Rumbek, to join the team coming

on the Redemptor. Once it reached the cataracts of the river Nile, the

boat had, unfortunately, to be abandoned and the impatient missionaries

had to proceed on foot.

This might have been a blessing in disguise for the Italian missionaries

who wanted to approach the local people with a distinctly friendly method

suggested by their founder Daniele Comboni, namely to "save Africa

by Africans". The method will from now on borrow much from the

African value of community life at meal. Salvation must be based on

sharing a meal with each other.

The Eucharist basis:

The first impressive manifestation of faith in the area was seen on

18th January 1910 when Mgr. Geyer's group arrived at the Commissioner's

house in Gondokoro to a warm welcome by a large crowd lead by a Catholic

employee from Goa, a certain "Mr. Dias, and many Catholics from

Uganda, easily recognised by the crown they carried on their necks".

The Ugandans had settled in that place as soldiers, servants and traders.

The following day, 19 January 1910, Mgr. Geyer celebrated Holy Mass

in the house of one of the sergeants, a catholic from Uganda.

Msgr. Geyer was very pleased by the large congregation and by

their faith. Relations with the authorities, though, did not go so well.

Monsignor's obedience to and patience with government administrators,

love for and trust in the "underprivileged" people and the

urge to go whenever the need arose, became the characteristics of a

typically Comboni missionary's apostolate in the Equatorial Nile Prefecture,

laying the foundation of a loving and zealous community headed by the

martyrs Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa.

The difficulties encountered in setting up missions were quickly

felt, not only on account of lack of material means, but also due to

contrasts, oppositions and mistrust. "On 2nd February 1910 we arrive

at Nimule, a lovely fertile piece of land where the small Unyama meets

the Nile and Koba rivers, just on the right side where the Nile enters

Lake Albert and turns on its course. The desire to settle here is irresistible.

But all will depend on the governor who, with some discomfort, witnessed

the large congregation at the first Catholic Mass.

The Commissioner, Mr. Hannington, son of the Protestant

bishop assassinated in Busoga on 29th October 1885 by order of the

Buganda's King Mwanga, has cautiously suggested a temporary settlement

at Nimule, but the final decision is still to come" (Negri A 1937.14).

A new English Commissioner had just arrived and Mgr. Geyer's attempt

to explain his position by referring to the recommendations of the Governor

General of Khartoum was in vain. Though uncertain of a permanent stay,

the caravan settled on a site by the regular Butyaba-Nimule route link

(Negri A. ibidem).

The favorable answer to Msgr. Geyer's request for a place where

to settle arrived four days later, but the message was not given to

him straight away. In those days, in fact, the ex-president of the United

Sates of America, Theodore

Roosevelt, was visiting the area with 600 porters and set up camp

just next to Msgr. Geyer's spot. Msgr. Geyer was finally handed over

the permission to open a mission station at Nimule, by the Lake Albert,

near a government post. Koba was suggested as the place for a permanent

mission station.

An interesting thing that Msgr. Geyer recalls was that the Shilluk,

when asked the name of the river the Redemptor was on, they said: Ni

lo? - meaning who knows?- a mystery indeed (Cisternino Mario 2000).

Indeed the missio ad gentes had started off on a mystery course, partly

revealed by the events that took place in Paimol, at Wi-Polo. Msgr.

Geyer, though, would never know of this event.

In the first months of 1911 a Protestant World Missionary Conference

was held in Edinburgh, Scotland. 1200 delegates from the remotest parts

of the world participated. At this conference a new approach to apostolate

of the CMS was discussed with specific appeal to collect a hyperbolic

sum of money to finance missionary activities in Omach.

The German representative, Dr. Kraff of the CMS, had already

sent a catechist to stay at Koba as early back as 1848. These two were

areas where the Comboni

Missionaries were just beginning their work, always behind the CMS

who enjoyed the government's favour.

5. Evangelization and

human development

From Koba Msgr. Geyer had free contacts with both the

Alur and Acholi neighbor's. He was planning to establish a second mission

station in the region. Soon Msgr. Geyer met with Alur and Acholi chiefs

to decide for a more permanent settlement among either of them. In Msgr.

Geyer's assessment, the Acholi were more primitive, difficult to trust

and warlike and so he would be rather careful before opening a mission

among them (Negri A. 1937.17-18).

On 6th March 1910 Mgr. Geyer blessed a cross for a church among

the Alur, at Omach. The converts were increasing. There was a clear

need for more labourers. Fr. Luigi Cordone and Fr. Pasquale Crazzolara

arrived from Italy with Bro. Clement Schroer and Bro. Benedict Sighele.

There was also the need to diversify evangelisation by taking into account

human development and education. Msgr. Geyer only had the time to bless

the new arrivals before returning to Europe to recover some strength.

Meanwhile the work at the mission continued with a new dimension

added, that of education. To the suspicious local population, it now

appeared clearly that the new white people were not interested in black

and white ivory. Fr. Pasquale Crazzolara was very well prepared and

keen to learn the local languages, Luganda

and Acholi, and to translate the catechism of Pope Pius X into the

Alur language to be used in their evangelising work. The text was in

a question and answer form, approved for catechetical instructions all

over the Apostolic Prefecture.

Fr. Albino Colombaroli was the superior of the mission. Children

were coming from all over the place to see the Comboni Missionaries,

the new white people whom they soon referred to as the munu karatum

- the people from Khartoum (Negri A Op. Cit 18-20). The Acholi chief

Lagony, who had sixty wives, was very happy to send one of his children

to the new munu. Soon the people willingly sent their children to the

friendly munu karatum who had truly come to teach them the way to heaven,

to WI-Polo

6. Fr. Beduschi and

Fr. Pietro Audisio settle among the Acholi

The Alur chief Okelo of West Nile, whose territory used to be

under Belgian authorities due to the first Anglo-Belgian treaty of 12th

May 1894, repeatedly kept sending one of his pages, a certain catechist

Areni, to call the new munu to his quarters to teach him catechism.

Fr. Colombaroli, who occasionally visited him, had to enter the Lado

enclave, still under Belgian authority.

When the Belgian King

Leopld II died, 17th December 1909, a second Anglo-Belgian treaty

transferred the Lado enclave under British

authority. The missionaries were then free to visit the West Nile

and Acholi areas. On 28th April 1911 Fr. Giuseppe Beduschi and Fr. Pietro

Audisio, from Verona and via Omach, arrived among the Acholi to open

the new mission of Gulu.

As the number of catechumens was steadily increasing, the Comboni

Missionaries turned for help to the White Fathers who had at hand

a good number of trained Bunyoro catechists. Knowing that an indigenous

catechist would do better in his own environment, as he is familiar

with the situation and enjoys the trust and love of the people, the

Comboni missionaries avoided the mistake of employing many catechists

from outside.

The administrators of the protectorate and the Protestant Church

Missionary Society (CMS) had been employing many Bunyoro people in various

positions. For Gulu mission, the missionaries asked just for three catechists.

These were granted by the Apostolic Vicar of Uganda, Msgr. Streicher.

By the middle of 1912 Fr. Colombaroli brought to Gulu Fr. Giuseppe

Zambonardi and Bro. Luigi Savariano. Fr. Zambonardi was to found the

new station of Foweira (Payira?) on the left bank of Victoria Nile,

just near Kamdini. Foweira, unfortunately, was not suitably placed to

serve both Omach and Gulu.

In September 1912 Fr. Colombaroli and Fr. Zambonardi abandoned

Foweira and moved to Palaro, on the opposite side of the bank, where

on 19th October they settled in the village of the great Palaro chief

Rasigala and there they founded the first Palaro mission station. Palaro,

one of the oldest slave markets, needed a special approach.

7. In Kitgum, en route

to Paimol

At the beginning of February 1915, Fr. Vignato and Fr. Beduschi

left Gulu for Kitgum, which is on the mouth of the river Pager, just

about one Km from a government settlement. They reached the place on

the 11th of the same month, feast of the apparition of Our Lady Immaculate

of Lourdes.

They burned the tall grass and cleared they had selected for

the new mission. A month later, in March 1915, Fr. Gian Battista Pedrana

and Fr. Cesare Gambaretto joined them. Bro. Poloniato arrived a little

later and they all finally settled down.

On 7th May 1915 Fr. Gambaretto writes that, ever since they had

arrived there, he was happy to report that they were having many people

coming to them for instruction, including an eleven-year-old boy who

already knew all the prayers and the songs, as he was at the Protestant

mission, but went to the new missionaries because he said: "we

want God". "The [Catholic] school is well developed",

continues Fr. Gambaretto, "and in the morning we have up to fifteen

children coming around. In the evening we have up to fifty boys who

sleep in the huts near us, among them eight sons of the local chiefs.

The Protestant arrived here before us and made converts. Thank

God we had prepared a handful of catechists whom we posted earlier on

in this area. These are the Catholics catechists posted in the following

places:

The head catechist Bonifacio Okot in Kitgum;

The 52 year-old catechist Elia Adeka in Omiya Pacwaa;

Romolo Olango in Wool station;

The catechist Antonio in Paimol.

Antonio was a cousin of Daudi

Okelo. As it happened, when Antonio died, Okelo volunteered to take

his place as catechist in Paimol.

8. Daudi Okelo of Ogom

Payira and Jildo Irwa of Labongo Bar-Kitoba

Generally speaking, one can never know with certitude of two

things about African people: one is their naming and the other is their

age. This is especially true of bygone times, because names were, and

still are, given to remember a particular event or situation. As for

the age, this was not date-recorded in the way western taught us to

do today. Besides, African people always considered it bad luck to list

names and to enumerate persons.

Okelo, in fact, is the Acholi name given to a child who follows

a sibling born in a certain way or who has a special mark. Are considered

such those children born by the legs first instead of the head or born

with defects of any kind, like six fingers, and so on. Such a child

is called Ojok if a male and Ajok if a female. Okelo, therefore, is

a true Acholi name given according to an Acholi custom and with a traditional

religious significance.

The martyr Daudi Okelo was born of Lode (father) and of Amona

(mother) in the village of Ogom-Payira. The larger Acholi sub-clan,

Payira, was headed by the sub-chief Awich, son of Rwotcamo who had been

killed in battle while fighting the Padibe clan in 1887. Around 1830

the Payira clan numbered between ten to fifteen thousand people, spread

in about thirty village-lineages, whose location was the central zone

of Acaa river, east of the Nile.

One of these thirty village-lineages was Okelo's Pa-Ocota village-lineage,

situated in Ogom-Payira, a few km to the east of the mouth of the river

Acaa. Here Daudi Okelo was born around 1902. This date is only a conjecture

based on the mission baptismal register. Okelo's parents lived and died

in their traditional religious practice. Okelo's world was more open

than his parents', since he came in touch with the white missionaries

and other foreigners. Lode and Amona brought up Okelo very well and

they would have loved to see him grow and settle down to form a family

according to tradition.

Equally significant is Irwa [Ermene]Jildo, also an Acholi from

Labongo Bar-Kitoba. Ir-wa's literal translation means "of-us"

or "ours". It is an endearing name among the Labongo. Now,

perhaps, the meaning of his name will take up a missionary dimension:

that of belonging to a new people, as the whole Church would say of

[Ermene]Jildo: "Irwa - One of ours".

Born of Okeny, better known as Tongfur and of his mother Ato,

Irwa lived in his Labongo village south west of Kitgum, in the same

direction as that of Okelo. Labongo, like Payira, was a subdivision

of the greater Acholi ethnic group. In about 1917 the Labongo people

migrated to Olworngu, a short distance east of the present Bar-Kitoba,

where previously the other Labongo village-lineages of Gem, Koch, and

Parakono had migrated.

For the purpose of pastoral care, the missionaries had divided

Kitgum Mission into two sections, at exactly the 32° latitude, so

the whole eastern section would be looked after by Fr. P. Audisio and

the western section by Fr. C. Gambaretto. Irwa's village was situated

in Fr. Gambaretto's area. Naturally, it was Fr. Gambaretto who first

met Jildo in the catechumenate.

Irwa's mother, Ato, died when he was very young and his father

Tongfur married again. Tongfur's second wife, Akelo, brought up Irwa

with great affection, as he was the only male. Akelo gave birth to four

girls. Though orphaned at an early age, Irwa knew how to repay love

with love. As he experience so much family love, he was able to share

this love and even his life with others to the extent of martyrdom for

the sake of Christ's gospel. His great heart would meet yet another

great heart, that of Daudi Okelo, and both together strived to share

God's love with all by bringing their people to WI-Polo, beginning with

the marginalized and so-called inferior, living in the third district

of the Nile Province.

9. Okelo and Irwa as

catechumens at Kitgum

From Kitgum mission station, Fr. Gambaretto often went to meet

the children in villages where he prepared them for the catechumenate.

The formal meeting in villages was commonly known as lok-odiku: literally

translated as "the morning words" or morning lessons. Once

the period of lok-odiku was completed, the children received medals

that they wore on their necks. This period lasted one full year, after

which one was admitted to the catechumenate, known as lok-otyeno: literally

meaning "the evening words" or evening lessons. Lok-otyeno

lasted two full years. During this period the children lived at the

mission. At the end of it, they received baptism and first holy communion

and were given a crucifix to wear around their necks.

Okelo's village of Ogom-Payira can still be seen lying by the

side of the present Gulu-Kitgum route, which, in all probability, is

the same old caravan route followed by the first government administrators

and missionaries. Due to his location, the village has certainly being

exposed to contacts and influence of what was going on more than the

other interior villages of the area.

Around 1913 Okelo came in contact with the Catholic missionaries

who, from Gulu, had been surveying the area east of Acaa river in search

of a suitable mission station. Okelo was old enough to stand on his

own two small feet when Mgr. Geyer's and Bro. Cagol, coming from Gondokoro

along the route of the Ni-lo, first tracked their way to Kitgum and,

later missionaries, to Paimol and, mysteriously, all the way to WI-Polo

Having completed the one year-period of lok-odiku in their villages,

Daudi and Jildo went to Kitgum mission for the lok-otyeno, which they

also completed together on 1st June 1916. They both went on to receive

the necessary instruction for confirmation that they again received

together on 15th October 1916. As catechumens in the mission Daudi and

Jildo excelled for their intelligence and kindness.

Oloya Cirillo of Kitgum, who was in the catechumenate together

with Daudi

and Jildo, says about them: "They were very good. Jildo was

a scullery-boy at the sisters' house". Adamo Opoka, who was head

catechist of Kitgum at the time, says "The two conducted themselves

in an exemplary way, which was the reason why they were put in charge

of the other catechumens".

10. A generous offer

to evangelise Paimol

"But they will not ask his help unless they believe in him,

and they will not believe in him unless they have heard of him, and

they will not hear of him unless they get a preacher and they will never

have a preacher unless one is sent…" (Rm 10:14-16). Great

apostles love and treasure these words of Paul.

Daudi and Jildo learnt them from the missionaries and they applied

them to themselves till the end. Daudi's older cousin, Antonio, was

working as a catechist in Paimol. When he died, the place was left with

no catechist, with "no preacher to spread the good news".

Young Daudi went to Fr. Gambaretto, the missionary responsible for Paimol,

and asked: "Who is to go to replace my cousin in Paimol?"

"I have no one to send", replied the missionary.

The following day both Daudi

and Jildo presented themselves to Fr. Gambaretto with an idea on

how to remedy the situation. Daudi said: "Father, if you wish,

Jildo and I could go to Paimol to replace Antonio". The priest

immediately told them about the difficulties and dangers lurking in

the remote zone of Paimol. The youngsters still insisted. The priest,

then, dismissed them, but reminded them, if they were serious about

their proposition, to return the next day.

The next day the two youngsters were back. Fr. Gambaretto asked

them: "So you are set in your mind to go to Paimol? Are you sure

you know the risks you are taking? Do you know that the people of Paimol

have not yet been properly subdued by the government? And you Jildo,

you are still small, can you make it to Paimol?"

The difficulties and dangers in Paimol the parish priest was

talking about were mainly the famine, which followed the 1916 long drought,

the Spanish fever that broke out in the same year, the hostile rebel-groups

or remnants of the munu jadiya who now felt even threatened by the Christian

religion, the local witches and witch doctors who were constantly loosing

adherents who were more inclined to follow the religion of munu karatum.

Daudi, the senior of the two, answered: "We will stay together"

The parish priest retorted "But what if they kill you?"

"We shall go to wi-polo, to heaven. Antonio is already there. Isn't

he?" Then continued: "I do not fear death. Did not Jesus also

die for us?" Jildo, who was looking at the priest somehow taken

aback by these words, took up from there: "Father, do not be afraid.

Jesus and his Mother Mary are with us". At last the priest gave

in. He went into his room, collected the catechism of Pius X, the one

translated by Fr. Crazzolara, some prayer booklets and the rosaries,

which he handed to them. Still under the verandah, the priest asked

Daudi and Jildo to recite an Hail Mary together and then blessed them

for their mission in Paimol.

11. At Paimol they "taught

religion very well and convincingly"

Daudi

Okelo and Jildo Irwa left their beloved villages of Ogom-Payira

and Labongo Bar-Kitoba and, accompanied by the head-catechist Bonifacio

Okot, went to Paimol to carry on the work of Antonio. The faith, fortitude,

love and generosity that filled them on their journey cannot be comprehended

but in the light of the sacrament of confirmation they had just recently

received and celebrated. They were truly burning with the zeal to evangelise

Paimol.

The catechist Bonifacio introduced them first to Ogal, the mukungu

or the appointed sub chief of the area. Ogal kindly welcomed the two

young catechists and was so generous as to offer them food and drink,

a great symbolic gesture that in the Acholi tradition signifies hospitality

and respect for the lives of the people concerned. The youngster were

allotted a fairly sizable hut next to Ocok Mukomoi, a brother of Ogal.

They settled and lived there for the rest of their stay in Paimol.

As trained by the missionaries, they employed the same method

of apostolate by going from village to village, visiting and making

friends with everyone, especially the children who would become lok-odiku.

The main task was to preach the word of God, "pwonyo dini"

in Acholi. For the children staying with them, the daily timetable consisted

of: work in the fields in the early and cooler morning, beat the drum

to call the children from work and to assemble next to the hut of the

catechists, teaching the lok-odiku beginning with with morning prayers.

Now and again the priest or a head catechist would come around to see

how everything was going.

Daudi and Jildo were often visited by the catechist Antonio Adyanga

and testified that the children loved to come and crowd around Daudi

and Jildo. Gabriele Aloo, who was one of the catechumen in Paimol, said

"Not only we children, even adults loved Daudi and Jildo, because

they taught religion very well and in a convincing way".

12. Hostility against

religion 1916 and 1917

The period 1916 and 1917 went down the annals of the missionaries

as a difficult and trying period in the evangelisation history of Acoli

land. Smallpox and famine broke out and the local population took to

superstitious remedies. The catechists came in strongly with the proclamation

of the good news of salvation, right up at the very administrative center

of Paimol.

Apprehensively people began to ask the diviners to explain the

cause for the small pox and for the famine. The diviners, many of whose

clients were converting to the new religion, at once found faults with

the religion of munu karatum and with the people who preached it, namely

the catechists. At about this time, Paimol's chief Lakidi was deposed

and incarcerated for a time in Kitgum. He patiently served his short

prison term.

After his release, again Amet, the vice-chief, accused him of

plotting against the local colonial administration in Kitgum. This time

Lakidi did not take it lying down. He fled to the jungle where he met

the rebels adwi Abas and others. There in the jungle a plot to resolve

their political aims and to put an end to the new religion was hatched.

The execution of their plot was planned and carried out in details,

each group knowing precisely which place and which person to attack.

In fact, one group went to attack the village of Amet, a second group

to attack and kill sub chief Bongi and the third group to kill the two

catechists.

In order to kill the catechists it was necessary to have someone

who knew them well. Opio Akadamo, Ibrahim Okedi, Odong and another Ibrahim,

all people from Ogal's village, were selected for the task. It was the

weekend of 19-21 October 1918. The catechists, after reciting the evening

rosary with the catechumens, were asleep in their hut.

The party set off long before dawn, at the second cockcrow according

to African chronology. In a few hours the catechists and catechumens

would wake up at the sound of the drumbeat for morning prayers. But

this morning they would unexpectedly wake up at WI-polo, in heaven,

our future place, as the two catechists had been teaching.

13.

The actual killing of Daudi and Jildo

13.

The actual killing of Daudi and Jildo

On reaching the village of the sub chief Ogal, the assailants

moved towards their hut., Ocok Mukomoi, Ogal's brother and the catechists'

neighbor, must have been woken up by the attackers footsteps and voices.

He went outside his hut and addressed the intruders by asking them what

they wanted.

When he realised that they were murderers who had come for Daudi

and Jildo, he entered into a heated argument with them in defense

of the two catechists. Okedi Ibrahim and Opio Akadamoi ignored him.

In the meantime Daudi, realising what was going on, came out of his

hut and kindly asked Ocok Mukomoi to let those people carry out what

they had come to do.

Seeing that the assailants did not want to listen to him, Ocok

made a sign to Daudi to run away, while continuing to plead with the

men to respect the symbolic gesture of respect for life accorded to

the catechists when they ate food and drank water from Ogal's house.

"Do not kill them here in my place for they have already eaten

and drunk here. Kill them outside, if you must." As Daudi did not

run away, the killers grabbed him and led him outside the village compound.

Then Okedi Ibrahim dealt him a mortal blow with his spear.

On realising what had happened to Daudi, Jildo also came out

of the hut and asked the killers to kill him as well since he too had

been teaching religion together with Daudi. "If you killed him

because he taught religion, kill me also, because I also taught religion

with him". They, then, dragged him away and Opio Akadamoi struck

him dead with his spear".

14. Fame of martyrdom

Today, in the year 2002, eighty-four years after their martyrdom,

we celebrate the death of Daudi

Okelo and Jildo Irwa. How did we come to know so much about them?

First of all our elders have a long memory of the important events that

happened in the village, and certainly could not easily forget what

happened on that weekend of 19-21 October 1918.

They remember many details about the killing of such two good

catechists who were truly loved by all. What they had done with the

bodies of the two youngsters was something unusual in that the bodies

had not been buried the way ordinary dead persons were buried. Their

bodies were taken to and left to rot over an empty termite anthill.

This very unusual gesture could not have been easily forgotten and showed

that the local people regarded the two catechists and their death something

special.

In 1927 Mgr. Antonio Vignato collected their remains from Paimol-Palamuku,

where they had been left, took them to Kitgum and buried them with honor

in the large Church of Kitgum, which had just been completed four years

earlier in 1923. Even after their remains had been removed from Paimol-Palamuku,

the Christians of the area continued to go and pray at the anthill,

already venerated as a special place. It was even renamed WI-polo ("in

heaven"), in remembrance of the prayer Daudi and Jildo had taught

to the catechumens in Paimol: "Our Father who art in heaven…".

Moreover, the villagers actually started to bury their dead up

at WI-polo, transforming the place into a Christian graveyard. Many

parents also named their children after Daudi and Jildo. The great uncles

of Jildo composed a bwola, a royal song in his honor.

In 1951 the Comboni Missionaries Fr. Vittorio Albertini and Fr. Vincenzo

Pellegrini were asked to collect some testimonies of the alleged martyrdom

for a possible opening of a canonical process.

Though records were collected in 1952-1953, the process could

not start then due to a number of reasons, like the lack of expertise

to undertake the study of the cause, the First and Second World Wars,

the anti-colonial feelings that the Comboni

missionaries met by the hands of political progressive parties in

Uganda, the increasing government's religious bias in the late fifties

and early sixties and the post independent Uganda periods of Milton

Obote in 1962-1970 and of Idi Amin Dada in 1971-1979.

The Gulu diocesan

synod of 1996 proposed to take up the canonical process and study of

the two catechists' martyrdom in a professional way. And with the expertise

of the Comboni Missionaries, Fr. Arnaldo Baritussio, in Rome and Fr.

Mario Marchetti in Gulu, Uganda, and of the diocesan priest Fr. Joseph

Okumu, the diocesan process opened in 1997 and closed in 1998. Almost

on record time, on 23rd April 2002 a decree of martyrdom was issued

by the Sacred Congregation of Saints for Blessed

Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa.

On 20th October 2002, Mission Sunday, the Pope

in Rome will declare blessed the two martyred catechists and present

them to the entire Church. It will be a recognition of Daudi

Okelo and Jildo Irwa's service for the "missio ad gentes"

and a reaffirmation that "there are martyrs even in our time",

in the third millennium, who have irrigated the soil of the Church along

the Ni-lo. In Uganda there will be two more crosses shining in the sky,

in addition to the earlier twenty two, binding a divided country in

a mysterious way through the cross on which Our Saviour died.

Many people, in north Uganda, who know Daudi

and Jildo find in them a model of zeal to share Christian values

with other people i.e. to evangelise. Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa teach

us that the Catholic Christian faith has two essential dimensions, the

personal and social. At the personal dimension, Catholic Christian faith

is received as a gift of God revealed to us and at its social level

this faith must be put shared out to the benefit of other people.

Daudi Okelo received the faith from the Missionaries of Italy

and thereafter felt the need to share it out in Paimol. In this way

Daudi

and Jildo teach us here in north Uganda that when we take our faith

seriously that faith easily becomes love of one another. This is what

many other catechists after Daudi and Jildo did in north Uganda. During

the on going insurgency, 66 catechists have been killed by combatants

as they went around rendering services to their needy brothers and sisters

in the Archdiocese

of Gulu. They remained in their places of work and service until

death because they understood that "a man can have no better love

than to lay down his life for his friends".

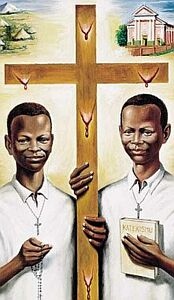

In the St. Joseph's Catechists Training Institute of the Archdiocese

of Gulu, the catechists always looked at the painting of Daudi

and Jildo and although they had not yet been declared martyrs, they

followed their example of strong faith and zeal to share that faith

with all peoples. The fame of martyrdom of the two young catechists

remain alive in the hearts of all student catechists. Catechists of

the Archdiocese of Gulu, like their companions Daudi and Jildo, are

always ready to go to preach gospel values to their own people thus

bringing to reality what Pope Paul VI had predicted when in 1969, he

talked of Africans being missionaries to themselves.

15. Conclusion

Wisdom says one thing about life in many different ways viz.

History repeats itself, nothing is new under the sun, a fool can only

learn by his own mistake. But there is one best way to put all these

sayings together. Life is learning, now, from the past to become better

in the future. In other words it is to know how to fit well together

the past present and the future. Martyrs like Daudi

Okelo and Jildo Irwa said it is to live in Faith, Love and Hope.

Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa are known as martyrs of evangelisation

because of their zeal to go and preach the gospel of love some eighty

kilometers away from their homes. This seems to be a very simple thing

which anyone would be in a position to do in theory. But today Ugandans

know how difficult it is to go and export the gospel values of love

to neighbor's. Daudi

and Jildo had all reasons to fear Paimol people and areas but they

decided, in the name of Jesus Christ, to look at the good results which

their mission would bring to Paimol without counting the cost. This

is a zeal that may look in a world torn apart by ethnic differences

but it truly happened and still happens.

Recently Ugandans remembered a catholic priest of Kasaana Luwero

who was killed in an ambush in Burundi. The national and independent

dailies paid tribute to him. Gulu

archdiocese remembers that over 66 catechists have still been killed

where they went to export the gospel values of love. Many Ugandans have

learnt to appreciate the zeal to evangelize and now that they have concrete

models of their own stock they should love to be more zealous.

Political situation has not completely changed from what it used

to be in 1918. When you recall the imposition and arrest of local chiefs

by the British administrators of the time and their attitude towards

the areas beyond Masindi, then you will realise that many African states

are still far from free and democratic. Blessed

Daudi and Jildo knew how to live in a situation of the same sort

with a tolerance inspired by faith and love.

When the killers fell upon the young catechists in their huts

they tried to dissuade them to teach the new gospel values in Paimol.

They would live if they stopped teaching it. But the two catechists

stood by their faith. Like Daudi

and Jildo we find it difficult to stand by our faith in the face

of opposition. If we want to stand firm in our convictions, Daudi and

Jildo will be our models.

Examples fervent faith

Blessed

Daudi and Jildo offer us a lesson in faith and fidelity. Of the

young martyrs, two things strike us with admiration; their young age

and the short time they lived their Christian faith with determination.

To them Jesus Christ was not a reality who could be chosen today and

abandoned tomorrow. The life according to the gospel, prayer, fraternal

charity, work and the desire to be instruments of evangelization, teaching

the new religion gave them confidence in front of all difficulties.

They felt that their service in Paimol, as catechists, entered

well into the plan of God by which the priests and other catechists

preferred them to others. For this they remained stronger and more matured

than other people of the place who asked them to abandon the new religion

and the church at the time of difficulty. They had said "Jesus

and Mary are with us" before they came to Paimol and now they must

show this practically. Great example indeed!

An examination of conscience for us today who easily give up

the true faith and the church for practices contrary to Christian faith.

These two lay catechists, who did not fear to witness their faith by

the shedding of blood, are an awe-inspiring example to the universal

Church and, more specially, to the Church in Uganda. At the dawn of

the third millennium Christians are invited to renew their faith in

a God who is always with them till the end of time.

Apostolic zeal

The lives

of two young catechists Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa are a testimony in

our own time of the truth of Christ's words. It is not just enough to

receive the great gift of faith but one must be willing and convinced

to share this great gift with others.

For Daudi

and Jildo, it all started with a simple but zealous question: "Father,

who will go to Paimol to take the place of Antonio?" This was a

question loaded with faith, love and hope of so simple and youthful

souls of Daudi

and Jildo. They wanted to go to evangelise Paimol, 80 or more kilometers

east of their own villages of Ogom-Payira and Labongo Bar-Kitoba.

Catechist Antonio of Paimol had died a year earlier in 1916.

The two of them feel that they must go to replace him. In this way the

great apostolic appeal apostle Paul must be obeyed also in our time,

"But they will not ask his help unless they believe in him, and

they will not believe in him unless they have heard of him, and they

will not hear of him unless they get a preacher and they will not get

a preacher unless one is sent" (Rm 10:14-16).

Apostolic zeal is always based on faith. Daudi

and Jildo had just embraced the faith and been confirmed in the

Spirit of God, and already, hardly a year later, they are willing to

go and propagate the new religion as catechists in Paimol. It was difficult

to serve as catechists in that part of acholi land. Faced with indifference

and lack of enthusiasms today every Christian learns from Daudi

and Jildo to be charitable and zealous to share all gifts with others.

Examples of responsibility

The decree with

which the Holy

Father Pope John Paul II acknowledges the martyrdom of Daudi

and Jildo reminds us that our two heroes had been notable disciples

of the Lord because of their good conduct.

By their lives, they preached what they themselves had received.

Just because they were real catechists, faithful to their mandate and

service they become examples to the local church and examples also to

each person who is part of the Christian community.

By their lives they appeal to both the catechists and all Christians.

They appeal to the youth and adults, individual and communities, church

and society and peoples of all walks of life to rest their lives on

stable spiritual and moral values.

Examples of Freedom

We may ask what

lessons Blessed

Daudi Okelo and Jildo Irwa may teach us today. Firstly, a lesson

of freedom. To be a Christian is to be free, free to make choices. Daudi

and Jildo attained this freedom by accepting to evangelise their brothers

and sisters. They were free to run away from Paimol when the situation

there became manifestly dangerous. They chose, instead, to remain, to

continue in their mission.

Even when they became aware that the adwi intended to kill them,

they still chose to remain. The choices one makes in life determine

the kind of person one becomes. Emulating Daudi

and Jildo we are invited to have that type of freedom of choices

that determines what we want to be, remembering that the best choices

are always life giving, love inspired, noble and generating peace.

Today, many young people rush to make choices very easily and

so they often go wrong. For example, the rash choices to use drugs,

heroines, join the army which often ends up in killing a person, etc.

are not a noble choice. The noble choices of Blessed

Daudi and Jildo do challenge us today. What have I done with my

life? Have I put my talents to the service of the Gospel or of Mammon?

Examples of truth and

justice

Daudi

and Jildo are a voice, which cannot be silenced, of truth and justice.

In fact in front of their killers they continued to proclaim their innocence

"you may kill us, but we have done nothing wrong".

The witnesses of their death also said "they killed them

[Daudi and Jildo] for no reason". These voices of the innocent

of all times must be remembered because they continue to remind us of

the grave responsibilities of those who use power to exploit, down trod,

oppress the weaker and the innocent.

The blood of Daudi

and Jildo cries against the injustices committed against the innocent

by those who continue to spill more blood for selfish interests. "The

blood of the just Abel... and of many others like him... among whom

there are also Daudi and Jildo, continues to ask for clemency, measure,

pity, justice compassion and truth!

Will our society hear them? The martyrs return again today in

our time". The Pope reminds us.

Examples of pardon and

reconciliation

Like Jesus and St.

Stephen, Daudi

and Jildo forgave their persecutors telling them of the meaninglessness

of their gesture. They told whoever wanted to kill them that their mission

would not be finished with their death even after they had been killed,

other catechists would have come to Paimol to continue the mission.

No one would anymore stop the preaching of the gospel in Paimol.

They did not deceive themselves because as we can see today all

the Christian communities prepare to celebrate the martyrdom. By their

heroic example to suffer the violence other than not, they call all

Ugandans, suffering and torn apart by ethnic and political divisions

to the only way to lasting peace and unity which is pardon, reconciliation,

justice and truth.

Responding to evil with, to violence with violence, to tyranny

with tyranny may give the impression of being very powerful or invincible

but in the end of the day it brings more insecurity in the country.

Daudi

and Jildo invite all to find a way different from the violent one

of the present.

The role of the catechist

today

The history of the

arrival and growth of Christianity in Uganda can only be fully explained

by the role of the catechists, persons who had been able to reach even

the remotest villages of the Christian communities. In effect, the catechists

have represented and continue to represent the basic Christian communities

of the church, priests and the people. They know both the priests and

their people better because they live with both better than anybody.

Today, catechists continue to be indispensable in the growth

and maintenance of the parishes and their outstations. In fact, they

are the immediate contact with the people of all places for an effective

and fruitful pastoral organization of the communities. Without them

the priests would have insurmountable pastoral difficulties in their

parishes.

The catechists therefore are vital and reputable leaders of the

people. They are, to sum it up, the indispensable point of reference

at all times. It is therefore understandable that in this part of the

country, concretely in the Archdiocese

of Gulu between 1986 and 2002 at least 66 catechists should have

been killed in the course of their ministry. The drama of these heroes

does not however discourage many others who still continue to come to

the training to take up the ministry.

At least there are still 630 working with ever stronger faith

to minister the word of God in the field and to reconcile with those

who do not agree with them.

By Joseph Okumu

Further reading:

Daudi

Okelo (1902 ca.-1918) and Jildo Irwa (1906 ca.-1918)

Who

were the Uganda Martyrs

Testimony

from Uganda

Archive: October News

Archive: September News

Archive: August News

Archive: July News