Chapter 1.

Provision of housing: Alms Houses.

Chapter 1.

Provision of housing: Alms Houses.EDWARD LAW

KILKENNY HISTORY

THE CHARITABLE INSTITUTIONS OF THE CITY OF KILKENNY FROM THE REFORMATION TO THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY.

A dissertation, with subsequent additions, undertaken as part of a University of Cork Diploma in Local Heritage Studies, Kilkenny 1994-1996.

Edward J Law.

CONTENTS.

Introduction.

Chapter 1.

Provision of housing: Alms Houses.

Chapter 1.

Provision of housing: Alms Houses.

Chapter 2. Provision of housing: House of Industry and Medicity Asylum.

Chapter 3. Provision of housing: Orphan House.

Chapter 4. Support for the poor: Outdoor relief.

Chapter 5. Support of small traders: Charitable Loan Society.

Chapter 6. Support for the poor: In death as in life.

Chapter 7. Provision for the sick: Hospitals.

Chapter 8. Provision for the sick: Dispensary and vaccination.

Conclusion.

Appendix (Magdalen asylum)

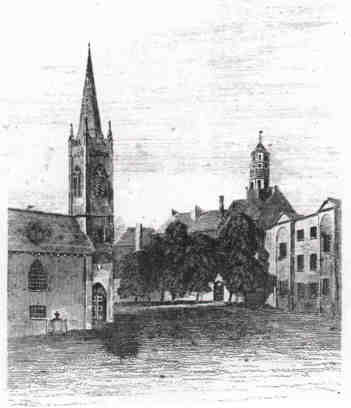

St Mary's church and Poor House (Lees Lane), 1842.

INTRODUCTION.

There has been in Ireland, from very early times, charitable provision for the sick and destitute. Brehon law laid an onus on territorial rulers to provide for the sick and homeless1. This system of voluntary care was continued on the introduction of Christianity, being particularly incorporated in the monastic way of life.

In medieval times the provision of charitable aid fell largely to the religious establishments. Food and shelter might be sought at monasteries, which also provided more long-term care for the infirm and probably for the elderly poor in general.

When the monasteries were dissolved by Henry VIII in 1541 no provision was made for the continuation of the charitable care they had provided, and numbers of infirm and sick poor were thrown upon the goodwill of the country at large.

The present work is a study of the institutions which served, through the ensuing three centuries, prior to the introduction of statutory provision in the Victorian era, to meet the needs of the sick and destitute of the city of Kilkenny.

Charitable support of the destitute took several forms: provision of accommodation; of finance; of food, fuel and other necessities of life; of employment; and finally, of burial. Care of the sick took place both in institutions and in the home. We shall see how all of these forms of charity were met to some extent in Kilkenny city in the three centuries to 1841.

Another, and major form of charity, which existed throughout the same period and which has not been considered in the present study, being worthy of a study in its own right, is that of charitable education.

The early form of charitable relief, through religious houses, was again coming into evidence towards the end of the period under consideration, for example through the work of the Sisters of Mercy, founded in 1836; this has not received the attention of the author. nor have the self-help groupings which emerged increasingly in the nineteenth century, for example the Society for Bettering the Condition and Encreasing the Comforts of the Poor, the Library Society and the Mortality Societies. A further class which has not been noticed are the charitable bequests of individuals (unless they led to the founding of charitable institutions) among whom may be listed Cramer, Chapelier, Fownes, Robertson and St Ruth.

The main source of information has been local newspapers which have been used extensively. For ease of accessibility those newspapers in the holdings of Kilkenny Archaeological Society have been used principally. However, because those holdings are incomplete several periods have received little attention, and there may be other local charitable institutions which had a limited life, awaiting rediscovery. Some original charitable records have been located and utilised. Secondary sources have been used where they have served to expand our knowledge of institutions. Parliamentary Papers have yielded small amounts of useful information. An unexpected, and useful source was the record of Charitable Legacies. The Registry of Deeds, anticipated as a useful source, proved entirely negative.

Reference.

1 John O'Connor The Workhouses of Ireland: the fate of Ireland's poor, Dublin 1995, p 17.

CHAPTER 1

PROVISION OF HOUSING: ALMS HOUSES.

The void in the care of the poor and the sick which existed after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1541 was filled to some extent by the erection and endowment of alms houses by wealthy individuals. Alms houses were the most numerous of the many Kilkenny charitable institutions; four were already established when George I took the English throne in 1714.

The oldest was the Shee Alms House, correctly styled the Hospital of Jesus of Kilkenny1, which was built by Sir Richard Shee and his wife in 1582 for six male and six female paupers2, it was endowed by the founder, whose family maintained support down to 17523, and continued in existence in the original building, which still stands, as late as the beginning of the nineteenth century4.

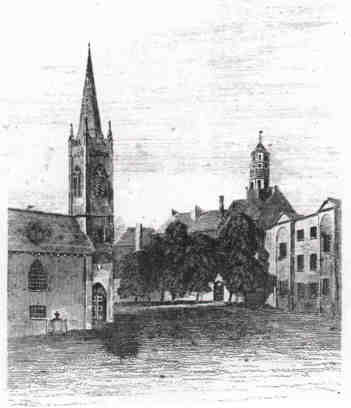

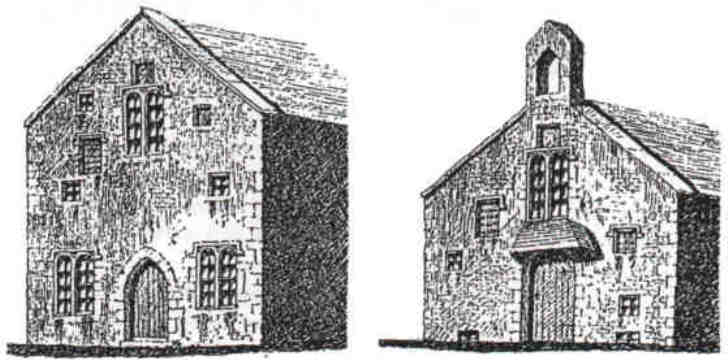

SHEE ALMS HOUSES, 1840. Left,Rose Inn Street frontage. Right, St Mary’s Lane frontage.

Reproduced from Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol III, 5th series, Pt I, p 81, and Pt III, p 299.

The second alms house was founded by the Earl of Ormonde, fittingly, for his family had been major beneficiaries under the dissolution of the monastries. Before his death in 1614 he ordained that a hospital should be built5, and a charter was procured in 1631 under the style of Hospital of our Blessed Saviour, of Kilkenny6. The Ormonde Poor House, as it is now known, continues to the present day, though translated c.18397 from its original site, at the south end of High Street, to Barrack Street.

THE ORMONDE POOR HOUSE.

The date of foundation of the two other alms houses in existence in Kilkenny prior to 1700 is not known. One was founded at St. Canice's Cathedral by Bishop Williams8 who was at St Canice's in 1641 and subsequently from 1661 to his death in 16739. In his will he left lands for the maintenance of eight poor widows "for whom I have erected 8 generall alms houses in ye parish of St. Keny"10. It was subsequently endowed by Bishop Otway who died 169311. It was described as tottering at the beginning of the nineteenth century12, and again in 1821, at which date a subscription was launched for its repair and enlargement13. The date of closure has not been established, it was still functioning in 185914.

The other, Fr. Tobin’s Poor House, was endowed under the will of James Tobin15 in 1699, though it may have been erected as early as 1682 when he took a lease of the land16, on the south side of Walkin Street, where the house was built. It continued to function down to 1963 on or close to its original site17.

The Georgian era was to see the foundation of several more alms houses. The best known of them is St James’s Asylum or Switsir’s Alms Houses which were built in 1803 by James Switsir, of, Dublin18, to house twenty indigent females. They still stand, recently refurbished, an adornment to the city and an enduring memorial to the charity of their founder.

SWITSIR’S ALMS HOUSES,

The founding documents of the Ormonde and Shee alms houses do not appear to have made any stipulation as to the religion of the ‘brethren’. Fr. Tobin's establishment, associated with the Friary, would almost certainly have been restricted to Catholics and that at St. Canice's Cathedral, which adjoined the ancient library, to Protestants. Regulations relating to Switsir’s Asylum were recorded in an Act of Parliament19. Of the twenty inmates eight were to be Roman Catholic and twelve Protestant. The major discriminations were not of creed, but of sex, all were to be female, and of status, they were to be 'decent and respectable Persons, the Widows or Daughters of respectable Persons who should have resided in the County or City of Kilkenny, or County of Carlow, for Ten Years or more’. The requirement of respectability is further enlarged upon. None were to be admitted ‘who ever was a Servant, or the Widow or Daughter or Niece of a Servant’20.

Established in August 180321, the same year as Switsir’s Alms Houses, was a similar institution, the Lees-Lane Poor-House. The principal mover in the matter was Rev. Peter Roe, then a curate at St Mary's Parish Church22, in the city centre. At first a single house was rented, later two more were added, and in 1820 funds were raised for the erection of a new large and comfortable house which was to accomodate fourty-eight females23. Peter Roe, who became the minister of St Mary’s was a noted orator who preached extensively in England, and whose connections there donated large sums towards the new house24.

LEES LANE POOR HOUSE,

The establishment was funded by subscriptions, at 3d. per week, donations and charity sermons. The latter had raised £515 between August 1803 and 1 January 1819, whilst subscriptions and donations had brought in £709; the largest donation, £54, had been received from the officers of the Cavan Regiment, presumably at a period when they were billeted in the city25.

It is said that the charity was principally devoted to the care of distressed widows26, though an advertisement in 1818 stated ‘All poor persons, resident in the City of Kilkenny, who are desirous to have the Scriptures read for them, are entitled to relief.’ At that time twenty-three people were housed in the Poor-House and a further twelve people were receiving weekly relief27. It was quite clearly a Protestant charity. The Poor-House still stands within the curtilage of St. Mary's.

Joseph Evans who died in 1818 left a fortune for charitable purposes29. The centrepieces of his benevolence were to be two asylums, one for decayed servants, the other for destitute orphans29. One wonders whether the former was intended as a balance to Switsir’s Asylum which was definitely not for servants? For the establishment of this institution he left £2,500 and an annual income of £500 to meet running costs and the support of the twenty inmates, ten male and ten female30. He appears to have made no stipulation as to religion, ostensibly fairer than Thomas Switsir, but the selection of the inmates, lying with six trustees, three of whom were Protestant clergy, the others, the Mayor and Recorder of the city and the High Sheriff of the county31, invariably Protestants, was open to sectarianism.

EVANS' ASYLUM.

Evans' endowment did not confer on the city the full advantages which were intended, primarily, it would appear, because of misappropriation of funds We do not have the full picture, but in 1849 William Grace, the ‘late Secretary of Evans' Charity was put on board the Hyderabad convict ship’, destined for Australia32. As well as defalcations large sums were expended in legal fees, in 1848-49 over £500 was paid for the prosecution of William Grace, and just under £500 on account of a trial with the Bank of Ireland33.

References.

1 Journal of the Kilkenny and south-east of Ireland Archaeological Society Vol III New Series 1860-6l, p 318.

2 Ibid. pp 318-19.

3 Anon., Shee Alms House, Rose Inn Street, Kilkenny 1581-1981. [N. D., unpaginated].

4 Ibid.

5 John Hogan Kilkenny: The ancient city of Ossory, Kilkenny, 1884, p 220.

6 Idem.

7 Idem. and Dorcas Birthistle 'Alms houses of Kilkenny' in Old Kilkenny Review 1964, No. 16, p 61.

8 Edward Ledwich 'The history and antiquities of Irishtown and Kilkenny from original records and authentic documents' in Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicus, Number IX, Dublin 1781, p 491.

9 J.B. Leslie, Ossory Clergy and Parishes, Eniskillen 1933, pp 17-19.

10 Ibid. p 18.

11 Ibid. p 22.

12 William Tighe Statistical observations relative to the county of Kilkenny made in the years 1800 & 1801, Dublin 1802, p 520.

13 Moderator 24.3.1821.

14 Valuation Office, Valuation Register: Kilkenny city.

15 W Carrigan The history and antiquities of the diocese of Ossory Dublin 1905, Vol III p 365.

16 Idem.

17 Birthistle, op cit, p 62.

18 Katherine M Lanigan and Gerald Tyler, eds., Ki1kenny its architecture & history Belfast 1986, p 49.

19 50 George III, Cap. 108, p 2379.

20 Idem.

21 Moderator 24.3.1818.

22 Leslie, op cit, p 353.

23 Samuel Madden Memoir of the life of the late Rev. Peter Roe, Dublin 1842, pp 335-36.

24 Moderator 21.8.1821 .

.

25 Moderator 24.3.1818.

26 Madden, op cit, p 335.

27 Moderator 24.3.1818.

28 Moderator 11.8.1818.

29 Moderator 11.8.1818.

30 Moderator 11.8.1818.

31 Moderator 11.8.1818.

32 Kilkenny Journal 26.5.1849.

33 Kilkenny Journal 8.3.1848 and 7.3.1849.

Right: Gateway at Switsir's Alms Houses.

CHAPTER 2

PROVISION OF HOUSING: HOUSE OF INDUSTRY and MENDICITY ASYLUM.

A perennial complaint of the townspeople of Kilkenny concerned the number of beggars to be found on the city streets. This was a problem which probably dated from the closure of the monasteries, which establishments had been the means of support of wandering beggars. That the problem had been addressed in Kilkenny in the seventeenth century is clear from the mention in a petition1 of 1640 by Peter Roth fitzEdmond of "the great Kychin" he surrendered for "a house of Correction".

In 1787 it was reported2 that John Butler, in an effort to abate the nuisance of ‘the swarm of beggars that daily infest our streets’ was to build a House of Industry ‘where the old and infirm may always find an asylum, and the lazy and incorrigible be kept to hard labour and discipline’. Though the site had been chosen, close to the County Hospital, it does not appear to have materialised Tighe3, in 1801, stated that a ‘house of industry, or means of affording work to all’ was wanted in every district.

The matter was raised again in 1805 when a donation of £50 was offered4 towards the cost of erecting a house, but again it appears to have come to nothing. There was an organised approach in 1809 when the Bishop of Ossory chaired a meeting which returned thanks to George Bryan Esq., of Jenkinstown, for the offer of a large house and concerns in Patrick Street for the intended establishment, and resolved that the premises be examined by the local architect, William Robertson'.

We may suppose that Robertson felt the premises were unsatisfactory, and incapable of economic improvement for he was later to write6:

Robertson’s new building was commenced in 1810, on what was then the Waterford Road7. The erection proceeded very slowly. In April 1813 the election of ‘a Master and House Keeper for the House of Industry’ was advertised8, but was almost immediately deferred9 in consequence of additional work being needed to complete the building. In January 1814 it was announced10 that the House was ready, but it had still not been opened by mid-March11. It was open by early May12.

HOUSE OF INDUSTRY.

In September 1815 plans and tenders were sought13 for two places of solitary confinement, 8ft. by 10ft. with small yards in front, to be located in the yard of the House. Robertson was a very able architect and clearly had taken all the necessities of such an establishment into account in his original design. It is probable that the revisions by the committee were entirely grounded on economies.

At the meeting in 1809, which we may consider to be the beginning of the modern House of Industry, the terms of subscription adopted14 were £3 for an annual Governor and £20 for a life Governor.

When the House did finally open the Master and Mistress were Andrew Neelands, who had been manager of the Cotton or Lintown Factory at Greens Hill on the outskirts of the city, and his wife15. Neelands had been appointed by 4 May, on which day he was married16: his period of office was tragically short for he was dead by mid-September17. His wife continued in her appointment and he was succeeded by his nephew, Andrew Bustard, ‘a master of the art of spinning cotton18’.

It is clear from the previous occupations of the first two Masters that great importance was attached to the industry which the House was to 'offer' its interns. In 1819 several females were engaged in spinning yarn, and cotton wick was also being manufactured19. In 1826 a school was being conducted in the establishment20.

In the Cholera epidemic of 1832 the buildings were appropriated as a Cholera Hospital21. Some seven years later, when the first Ordnance Survey map was being prepared there was a reminder of that period in its history, for adjoining the ‘Workhouse’, ‘Solitary Cells’ and ‘Lunatic Asylum’ was a ‘Cholera Burial Ground’22. By 1837 the House of Industry and the attached Hospital for Lunatics was being utilised as an auxilliary to the County Gaol23. It was finally succeeded by the Union Workhouse in 184224, and there was talk the following year of it being taken over as a police barracks25. In 1854 it was offered for sale or to let as ‘late House of Correction with yard and 3 acres26, and the following year there were again proposals that it might be used as barracks27.

Pigot's Directory28 of 1824 records a mendicity asylum at Kilkenny, ‘lately established’, and newspaper references have been seen down to 182929. It was supported by balls30 and donations31, but what exactly its purpose was, who were the promoters and where it stood are not known. A report32 in 1821 of ‘An asylum now erecting on the site of the old Barrack’ probably refers, and the site may have been in Patrick Street where at one time were some temporary barracks33.

References.

1 St. Kieran's College, Kilkenny, Graves papers, 1/22.

2 Finn's Leinster Journal 17.1.1787.

3 Tighe, op cit, p 537,

4 Leinster Journal 19.1.1805.

5 Leinster Journal 21.10.1809.

6 Kilkenny Chronicle 29.10.1814.

7 Leinster Journal 11.8.1810.

8 Kilkenny Chronicle 8.4.1813.

9 Kilkenny Chronicle 24.4.1813.

10 Kilkenny Chronicle 15.1.1814.

11 Moderator 15.3.1814.

12 Moderator 5.5.1814.

13 Moderator 9.9.1815.

14 Leinster Journal 21.10.1809.

15 Moderator 17.9.1814.

16 Moderator 5.5.1814.

17 Moderator 17.9.1814.

18 Moderator 17.9.1814.

19 Moderator 5.8.1819.

20 Michael O'Dwyer 'Education in St. Patrick's Parish’ in St.Patrick’s, Kilkenny gravestone inscriptions with historical notes on the parish, Kilkenny, N.D., p 62.

21 Journal 12.5.1832.

22 Ordnance Survey Map, 6" to 1 mile, surveyed 1839-40.

23 Samuel Lewis A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, London 1837, Vol II, p 114.

24 Thom's Irish Almanack, 1853, Dublin 1853, p 275.

25 Kilkenny Journal 18.6.1843.

26 Kilkenny Journal 22.4.1854.

27 Kilkenny Journal 14.3.1855.

28 Pigot & Co's. City of Dublin and Hibernian Provincial Directory, Manchester 1824, p 160.

29 Moderator 3.3.1827 and 18.2.1829.

30 Moderator 18.2.1829.

31 Moderator 13.6.1829.

32 Moderator 20.10.1821.

33 Moderator 18.1.1821.

GO TO PART 2 (Chapters 3 to 6)

RETURN TO HOME

Page updated 14 October 2007