![]()

![]()

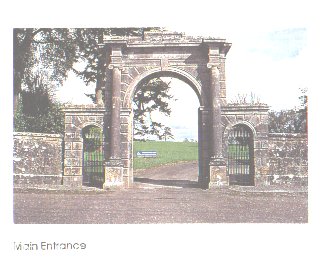

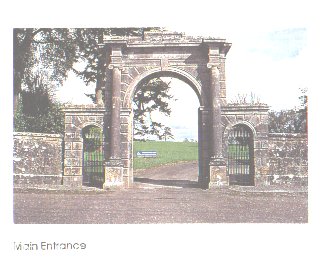

The fine entrance gates and the portico-ed gated lodge on the Turnpike Road, north of Doneraile town, mark the formal entrance to a great landscaped estate. At the time when the gates were erected - the last years of the eighteenth century or the first years of the nineteenth - the long process of laying the estate was complete, and Doneraile Park had been arranged in the shape that we see today.

The shape is of an estate where the guiding principles are beauty and the landlords pleasure, rather than utility or profit. The estate did have a practical dimension, as we will see - pleasure and profit went hand in hand - but beauty was the over- riding consideration. Only a wealthy man, living in fairly peaceful times, could afford to set aside four hundred acres of prime land for a landscaped park. The St. Leger family, which created this park, could do so because of their extensive land-holdings in North Munster. The income from these lands met the very considerable expense involved in laying out the estate, and building and embellishing the country house which is its focal point. The greater part of the work at Doneraile was undertaken in the early eighteenth century. The fashion in landscape gardening was exemplified, if not largely formed, by the achievements of the English landscape architect, Lancelot ' Capability ' Brown. Capability Brown landscaping is an art of illusion. The immediate impression created is that nature, not man, has shaped the landscape. The success of this illusion requires great skill and judgement - the art that conceals art. The dominant effects are extended prospects of undulating grassland. Within these are artfully set single specimens or clusters of broadleaved trees, mainly oak, beech, lime and chestnut. Bordering the great meadows are 'fringe belts', massed planting of broadleaved trees, to give the illusion that the meadows are clearings in the middle of woodland. Fences are sunk into the ground to avoid obstruction of the view.

In the hollows of the landscape, water is the important element, artificially diverted into canals, cascades and ponds, and spanned by elegant stone bridges. Eighteenth century water gardening is seen to good effect at Doneraile. The way through the park is along a system of avenues, designed to show all these features to the best advantage. The main avenue at Doneraile winds for a mile through the park on its way to the Court.

Of course, Doneraile was not always like this, and we can better appreciate the scale of what has been achieved here, if we know what it was like before the eighteenth century St. Legers.

An Anglo-Norman family, the Synans, were the power in this part of North Cork up to the end of the sixteenth century. They arrived in Ireland in 1172 as a company of bowmen in Strongbow's invasion force. They were at the zenith of their influence in 1402 when Mac William Synan Mor built a castle at Doneraile. However, the Synans became embroiled in the Desmond Rebellion of 1579-1582 and their fortunes declined as a result. Some of their lands were confiscated, and in 1636 they sold their lands at Doneraile to Sir William St. Leger, Lord President of Munster, 'for the sum of three hundred pounds sterling.'

The St. Legers belonged to the aristocracy of colonial administrators who rose to prominence under the Tudors and achieved fortune during the land confiscations of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. We first hear of them in Ireland in 1537 when Sir Anthony St. Leger was sent here by Henry VIII to oversee the dissolution of the monasteries. His grandson, Sir Wareham St. Leger, was chief governor of Munster. In 1600 he fought in single combat with Hugh Maguire, Lord of Fermanagh, before the walls of Cork. Both of the combatants died from the wounds they received in this encounter. It was Wareham's son, Sir William St. Leger, who bought Doneraile from the Synans. Prior to this transaction, he had been acquiring other landholdings in North Cork and Tipperary, and his position was strengthened by the grant in 1639, by Charles I of 'The Black Letter Patent of Doneraile Estate'. The St Legers were to enjoy unbroken possession of Doneraile Park until 1969, when the Department of Lands took over the remnants of their estate.

Sir William St. Leger established the Lord president of Munster's court at a castle close to Doneraile on the north side of the Awbeg River. One of his actions as Lord President was to ban hurling and football on the streets of Cork. The ban was enforced by the Corporation. Very likely it was for reasons of public order, because Sir William's descendants were known to be great sporting men.

When rebellion broke out in 1641, Sir William took the field against the insurgents. The strain of his combined military and administrative responsibilities were too much for him and he died the following year.In 1645 Doneraile Castle and part of Doneraile town were burned by the forces of the Confederate Catholics..

The castle was rebuilt some years later when the country was less turbulent. Around the castle were great formal gardens. Some idea of what these looked like is possible because of a map of 1728 which shows the castle gardens, and the gardens of the new house on the other side of the river.

Stretching south west of the castle were walled gardens. Within these were 'parterres', rectangular beds of clipped box hedging. The beds were planted with box hedging arranged in geometric or emblemmatic patterns. At right angles to the walled gardens, beyond the bowed wall, were terraced lawns. Immediately north of the lawns was 'The Beech Avenue'. North of this was the walled 'Upper Orchard'. Between the 'Upper Orchard' and the 'Great Meadow' was an 'Oak Grove'. South of the terraces was the 'Lower Orchard'. Between this and the river was a walled 'Fir Grove'. Another 'Fir Grove' was on the bank of the river immediately opposite.

Enclosed gardens, rectangular patterns, symmetrical lines of trees, were the features of the castle gardens. They had virtually disappeared by 1750. Only some of the walls and the Beech avenue survive. The line of one of the terraced lawns can just be made out near the present car-park. Looking across the river from this vantage point, it is evident what replaced them -- open vistas, gently curved lines, clusters of trees arranged to give the impression of 'natural' planting.

The landscape architect's art can be seen at its most beguiling in the diversion of the Awbeg river at Doneraile. What had been a single stream was diverted into several channels and small islands created. On one of the islands was a summer house for picnics and other outdoor recreations. Dams were built and canals made to form large pools of water in the hollows. The most elaborate of these dams was made of limestone and set in place between 1728 and 1750. The dam diverted some of the water of the river into a canal. The water from the canal cascaded over a weir into the large pool below the house. This weir was one of the features of Doneraile which most impressed Smith and Young. To those two intrepid travellers we owe much of our information on the landscape and the life of the people in 18th. century Ireland. Smith visited Doneraile in 1750 and Young was here in 1777. The dam broke down around 1920 with the result that the canal silted up and the cascade disappeared from view. A new concrete dam was installed in 1978, the canal was dredged and the cascade uncovered once more.

As well as being a thing of beauty,the weir also had a practical function. By speeding up the flow of water in the river, it increased the oxygen supply in the water and made it better for fish. In the middle of the dam is a fish pass with wooden slats alternately placed to allow spawning fish through. The river is being stocked with trout and salmon by the Fisheries Board. A fishery that was once the preserve of a privileged minority is now available to any angler who secures an angling licence.

Two fine limestone bridges span the Awbeg to the front of the house. The stone footbridge near the weir was designed to be seen viewed from the avenue. It is a complicated structure, going at an angle to the canal over which it is built. Its two arches are slanted in the direction of the stream. The most elegant of the Doneraile bridges is the triple arched bridge on the main estate avenue. It is highly decorated on the upstream side, as this is the side that would be visible to a person whether travelling to or from the house.

South of the river is the Lady's Well, fed by strong natural springs. The pipe of the 'ram' which pumped water to the house from the well is still visible. A ram was a mechanical device which used the energy from flowing water to raise some of the water to higher ground. An attractive feature of the Lady's Well wood is a natural rockery. In the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries the rockery was planted with woodland flowers among which the Christmas rose ( Helleborus niger ) was outstanding

Water is the dominant feature of the hollows of Doneraile. Trees are clustered or massed on the heights.

Most of the trees of Doneraile are very old. The splendid double row of beeches called the 'Beech Avenue' dates from the 18th. century and marks the line of what was probably an old road or avenue associated with Doneraile Castle.

The estate is noted for its fine oaks. Groups of them can be seen at many points, but they appear most impressively on the slopes above the Lady's Well Wood and the wetland area. Their survival in such numbers here is because the slopes were too steep to have allowed for easy clearing.

At one time the valley of the Blackwater and the area along the banks of the Awbeg were thickly covered with oakwoods. Timber from these woods can be found in buildings all over the world, and is said to have been used in constructing the roof of St. Pauls Cathedral. Because oak was the staple material for house and ship building all through the Middle Ages, and beyond, oakwoods were felled on a massive scale. The reclamation of woodland for farming and the use of oak for iron smelting, accelerated the rate of clearance, and by 1750 most of Ireland's native woodlands were gone. Native oaks now survive in any strength only in the mountainous areas around Glengarriff and Killarney.

Another ancient tree to notice in Doneraile is the Spanish chestnut, warped with age, on the slope above the river to the north east of the present car park. On the lawn in front of the house are two venerable larches. These are a mountain variety of the European larch (Larix decidua). Their branches slope down and out from the trunk so that the tree can shed heavy snow and ice without breaking the branches. This species was first planted in Ireland around 1738. Seeds were sent from Scotland by the Duke of Atholl, and the trees at Doneraile are thought to be part of this importation.

The elms at Doneraile succumbed to Dutch Elm Disease. Fortunately, they were never a dominant feature of the landscape and their disappearance has not left tthe forlorn gaps that have marred estates where they were more plentiful.

The Pleasure Grounds at Doneraile, on the garden side of the house, contains some unusual trees, including redwoods, Chusan palms and a Cork oak. Here also specimens of cherry, yew, variegated sycamore and plane. Alder has colonised the wetland areas of the park. It is not part of the original planting scheme but will be retained as part of the development of the wetlands as a sanctuary for wild birds. Ash has invaded some of the older planting. The ash is an attractive and useful tree, but it is out of place here and is being cleared to conserve the essential character of this historic landscape.

The focal point of the landscape at Doneraile, from which all the architect's splendid vistas radiate, is Doneraile Court. The date of the building of the house is uncertain. Some architectural historians believe that the basement dates from the late 17th. century, and it is likely that some of the St.Legers had a house on the site of Doneraile Court since the early 1690's. The first Viscount Doneraile may have occupied the house shortly after he got married in 1690. The date of 1725 over the porch would seem to refer to a major reconstruction of the house.This date has proved to be confusing because the most famous incident to occur at Doneraile Court was in 1712. Elizabeth St. Leger, the 1st. Viscount's daughter, eavesdropped on a meeting of father's Masonic Lodge being held in the library. Elizabeth was sitting in an adjoining room and apparently overheard the proceedings through a chink in the brickwork, which would indicate that the builders were then working on the house. She was discovered, and, although women were excluded from Freemasonry, made to take the masonic vows to preserve the masonic secrets. She thereby became one of only threefemale free-masons in history.

The remodelling of the house in and around 1725 was commissioned by Elizabeth's brother, Hayes St. Leger. It was he, also, who was responsible for the early 18th. century landscaping of the park. The architect he employed was Isaac Rothery. Rothery designed a tall three-storey house of seven bays, with a three-bay breakfront, blocked quoins, and crisply moulded window surrounds. This house closely resembled two other houses by Rothery, Bowenscourt in Kildorrery and Mt. Ievers in Co. Clare. Rothery also designed Newmarket Court in North Cork for Elizabeth's husband, Richard Aldworth. Mt. Ievers and Newmarket Court still exist but Bowenscourt was demolished in the early 1960's. The curved end bows on the front of Doneraile Court were added in the later 18th. century.

In 1805 there was a fire and this was followed by further remodelling of the house. The east or garden front was given two bows, and an orangery in Strawberry Hill Gothic style was added. The orangery has not survived. The classical porch was built on to the front of the house later in the 19th. century. In 1869, a large dining room, more Regency in style than Victorian, was added to the west side of the house. This became badly affected by dry rot, and has since been demolished, but it was a splendid room. At one end of the room was an alcove containing a vast mahogany sideboard. Reflected in the mirror of the sideboard was a full length portrait of the black-bearded 4th. Viscount Doneraile, resting an arm on his horse. He was one of the great Victorian hunting men, and his end was ironic and macabre. He kept a pet fox which was housed near the gate at the side of the court. The fox became rabid and bit its master. The Viscount contracted rabies and was smothered with pillows by the housemaids to spare him suffering and prevent him spreadind the disease to others.

A more pleasant memory of Doneraile Court has been left to us by Harold Nicholson, who was a guest here towards the end of the 19th. century. He was a connoisseur of country houses and gardens. The gardens at Sissinghurst in Kent were created by Nicholson and his wife, Vita Sackville-West. He describes how he sat in the orangery at Doneraile on a hot, wet afternoon, 'inhaling the smell of the tube roses, listening to the rattle of the rain upon the glass roof, listening to the gentler tinkling of the fountain as it splashed among the ferns'.

When it was first built, Doneraile Court faced onto a public road known as Fishpond Lane. The lane ran from Doneraile town, between the two fishponds and out through the South Park. It may have been a toll road - a large stone inside the perimeter of the South Park is known locally as the Toll stone. Holes in the stone indicate that it held a barrier or gate which was pulled back on payment of the toll. When Fishpond Lane was closed as a public roadway it became necessary to prevent the animals on the estate from trampling on to the Pleasure Ground on the garden side of the house. The 'ha-ha', the sunken fence on the inside of the Fishpond Lane, kept the animals out but did not obstruct the view towards the North Park

The most spectacular feature of the Pleasure Ground is the 'Lime Walk', leading down to the fishponds. Towards the end of the 19th. century the area just south-west of the Lime Walk,above the large fishpond, was enclosed to create a sanctuary for rare aquatic birds. Demoiselle, cranes and rheas, emu-like birds, were kept here, still known locally as 'The Bird Enclosure. A photo exists showing the rheas and their young posed above the fishpond. The effect was startling, and must have been much moreso for the stroller along the Lime Walk coming suddenly upon these tropical creatures. They have long since vanished but today one can see their replacement, another exotic species, Japanese Sika Deer. Sika deer were first introduced to Ireland in 1860 by Lord Powerscourt at Co. Wicklow. They are the smallest species of deer in the country. They have done very well in Killarney where the climate suits them, and the Doneraile herd were brought here from Killarney in 1984. Sika deer have a very distinctive white rump patch.

The fish ponds in Doneraile Park are said to the largest formal stretch of still water extant in Ireland. They were made before the house was built. Coarse fish, such as perch, carp and pike were stocked in the ponds and caught to supply the table. There are still perch, pike and roach here. A large water wheel, which was probably sited on one of the narrow streams flowing from the powerful springs in the Lady's Well wood, supplied water for the upper pond. The water came underground to the pond and cascaded out onto Fishpond Lane on its way back to the river. The wheel is long gone, and if there is a prolonged dry spell the waters of the fishponds go very low. During the 19th. century, the fishponds were a decorative rather than a functional feature. Water lillies were planted in the upper pond and became so rampant that they completely blotted out the water in summer. However,cleaning of large parts of the lily infested sections, and dredging, are restoringthe pond to something of its former state.

Both ponds are being developed as a wild bird habitat. Swans are the most elegant users of the ponds now, as always, and coots, moorhens and shovellers are established here as an advance guard for other species. The limestone subsoil is a rich breeding ground of the insects on which wildbirds feed. There is grazing for geese and ducks on the margins of the ponds.

Across the ponds, in the South Park, is a herd of Killarney Red deer. They were brought to Doneraile in 1983. Willows grow in the lowlying meadows between the South and North Parks In earlier centuries extensive plantations of willows - known as osier beds - were common along rivers and streams. The osiers provided scallops for fencing and thatching and cane for baskets and wicker furniture. This wetland in Doneraile is being developed as a wildfowl sanctuary.

Wetlands are important as the habitat of many native and migratory birds, and water-loving plant species. They are disappearing all over Ireland as a result of arterial drainage schemes. The development of this wetland is intended to help redress the balance in favour of wildlife conservation. When wetlands were still undrained, and wild duck plentiful, large country estates had duck decoys for trapping wild duck for the market. The Dutch produced designs for duck decoys in the 15th. century which were more efficient than anything that had been used before. Charles II commissioned a Dutchman to build one for him in St. Jame's Park in 1664. A spate of decoy construction followed and in the 17th. and 18th. centuries there were 22 decoys in Ireland. The one at Doneraile was in an area still known today as the decoy wood. Many of the decoys operated until the early 20th. century, but were allowed to decay when wetland drainage depleted the wild duck population.

This is how a duck decoy worked: netting was stretched over hoops spanning a shallow pond, thereby forming a tunnel which narrowed towards the end. At the narrow end was a detachable net. In some cases the wild duck were enticed into the tunnel by grain spread inside. Sometimes tame duck were placed in the tunnel to lull the wild ones into a false sense of security. Another method was to use a specially trained dog to lure the duck to their capture. At the concealed decoy man's command, the dog moved slowly along the outside of the tunnel. Curiosity led the duck to swim into the tunnel to see what the dog was up to. Whatever method was used, the decoy man closed the entrance to the tunnel when the duck were inside, and captured them in the detatchable net at the other end, Mallard teal shoveller and pintail were easily caught in this way, but wigeon, tufted duck and pochard were more wary of entering the tunnel.

Duck decoys are illegal in Britain and Ireland, except for special purposes such as catching wildfowl for scientific study. For this purpose the Wildfowl Trust of Britain maintains a decoy at Slimbridge in Gloucestershire. The Forest and Wildlife Service hopes to reconstruct the duck decoy at Doneraile for this use.

Along the deeper reaches of the river at Doneraile the patient watcher may glimpse the elusive kingfisher. This most dazzling of birds has body plumage of irridescent blue, with emerald green upper parts. When it sees its prey, it dives down straight into the water like a torpedo amd snatches it up in its dagger-like bill.

Another fish eating bird is the stately heron. The heron is easily seen because it spends long hours standing motionless in the river watching for fish or frogs. The heron is equally impressive in flight. At the beginning of this century there was a heronry of fifteen nests in the Pleasure Grounds at Doneraile Park, but by 1982 this had declined to only four.

The Awbeg at Doneraile is a good habitat for otters and an observant person will notice the print of their webbed feet in the mud along the river bank. Otters are shy of humans and are not easily seen. They are especially fond of eels, but eat other fish, frogs and frog spawn. Their 'holts', where they rear their young, are concealed at the base of trees whose root systems have been exposed by the actions of the river. Otters are protected by the Wildlife Act of 1976.

Access from the wetland area to the North Park is across the Hunting Bridge, the third of the stone bridges across the Awbeg at Doneraile.It is a hump-backed bridge with a single handsome arch.Its name is probably derived from its use as a crossing over the river for foxhounds.

The North Park is the largest area of grassland in Doneraile Park.It is planted with many fine old lime trees. The fringe belt is mainly of oak and beech, interplanted with some Scots pine and Douglas fir. It was probably enclosed as a deerpark in the early 18th. century and was well established when Smith visited Doneraile in 1750. He described it as ' an extensive deer park, well planted' . It was not, however, the first deer park in Doneraile. The map of 1728 shows a large deer park on either side of the river in front of the house. The natural habitat for deer is broadleaved woodland where there is a variety of plants for grazing, browsing and shelter. Deer enclosures on landowners estates date from the 16th. century. Deer parks provided venison for the table, and sport for the landlord and his guests hunting the stag. The first deer park in Munster was at Mallow Castle. In 1597 Elizabeth I sent two fallow bucks to the herd at Mallow. The first deer park at Doneraile dates from the mid 17th. century. During the 17th. an 18th. centuries many of the larger estates in Ireland had deer parks. Most of these parks were for fallow deer. The Doneraile fallow herd survived until 1913. The present herd of fallow deer in the south corner of the North Park were introduced in 1982. The Red Deer in the North Park are Doneraile Red, survivors of the herd introduced by the St. Legers in 1895. Unlike fallow deer which were introduced by the Normans in the 13th. century, and Japanese Sika which arrived here in the 19th.century, Red Deer are native to Ireland. When Ireland was covered with woodlands Red Deer were plentiful. But as demand for timber increased and led to the clearing of woodlands, the number of Red Deer diminished. By 1750 when most of Ireland's native woodland had gone, most of the Red deer had disappeared with them. Kerry Red deer are the only Red deer that can claim to be descende from the original wild stock. They survived because the natural woodland on which they depended for food and cover survived in the Killarney Valley and because the mountainous terrain there provided them with many hiding places inaccessible to deer hunters. They were also fortunate that the landowners who controlled their range, Lord Kenmare and Mr. Herbert ,of Muckross House, were conservationists and afforded them reasonable protection from exploitation. The Red deer herd in the South Park at Doneraile was brought there from Killarney in 1983. The origin of the Doneraile Red deer herd introduced to the North Park in 1895 is not known. The St.Leger family were very interested in sport, and we may assume that the Red stag was hunted with the hounds at Doneraile.Stags with particularly fine antlers were shot and their heads mounted at Doneraile Court. The size of the herd was regulated by annual culls of young males and females. The culls provided tender venison for the table. At Doneraile Court there is a large larder where the venison would have'hung'. Because of inbreeding over the years the herd of Red deer at Doneraile had deteriorated. To counteract this, the Forest and Wildlife Service has begun a program of outbreeding. Selected stags from the Killarney batchelors in the South Park are being introduced to the hinds on a rotational basis. The stag you see with the hinds now will be replaced by another next season, and so on for a number of years.

A crucial factor in deer farming is secure fencing. Deer are very agile and ordinary fencing will not contain them. To keep the Doneraile deer from escaping and eating the crops of neighbouring farmers, fences at least seven feet high, and tightly secured to the ground, are necessary. Antlers are grown and discarded each year. For the successful growth of antlers the stags need large quantities of minerals and trace elements, and it takes much foraging by deer in the wild to ingest all these nutrients. When antlers are growing in the summer months they are soft and spongy and covered in a fluffy skin called velvet. The velvet contains the blood vessels supplying the nutrients to the growing antlers. When the antlers are fully grown, the blood supply to the velvet is cut off, and the velvet withers and falls away in strips and tatters. In order to hurry up the casting of the velvet, the stags vigorously rub the antlers against young forest trees. The friction causes stripping of the bark and cambium layers and often results in the death of the trees. This damage is called 'fraying'.

Browsing and fraying by the uncontrolled Doneraile Red deerherd had decimated young tree growth in the Park, resulting in many over-mature trees and too few new trees to replace them. Effective fencing by the Forest and Wildlife Service has allowed regeneration of trees at Doneraile. Fencing also makes possible good grass management, ensuring a continuous supply of nutrients necessary for a healthy herd.

The stags use their antlers for fighting with other stags for possession of the females during the 'rut'. Mating seasons vary with Sika, Fallow and Red deer from August to November. Gestation periods vary from thirty two to thirty five weeks. Calving occurs from April to June. Some deer calves stay with their mother until her next calf is due to be born. Mature male deer live solitary, or in small groups, after the mating season is over. Immature males are chaperoned by the female herd. The oldest females are always the most alert, looking out for danger and leading the herd to safety. Since the wolf became extinct in Ireland, about 1786, man has been the main predator of the deer species. All deer are protected under the Wildlife act of 1976.

The 'ha-ha in the north west section of the North Park protected the lawns of the 'Doneraile Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club' from encroachment by the deer. This area of the Park is still known as the 'Tennis Ground'. The 6th. Viscount St. Leger was one of the founders of the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis and Croquet Tournaments. Just as they were interested in field and lawn sports. the St. Legers did not neglect the sport of kings. In 1752, the first 'steeplechase' was run from the steeple of Buttevant church to the steeple of the Doneraile church. In 1776, Colonel Anthony St. Leger founded the Doncaster St. Leger.

The St. Legers are now in their tombs in Doneraile church grounds.The seventh Lord Doneraile died on the 18th. December 1956. Lady Doneraile remained living in Doneraile Court while the Irish Government asked the House of Lords in London to decide whether an American cousin, Richard St. Leger, should inherit the estate. Based on the evidence provided by the Trustees of the estate, the House of Lords decided against this inheritence. In 1969 Lady Doneraile sold the six hundred acre estate to the Irish Land Commission, who, in turn, transferred four hundred acres and the house to the Forestry Commission. The Forestry Commission developed the Park , which was officially opened in 1984. The house remained empty for seven years and consideration was given to removing the roof, so that the property could be maintained under the National Monuments Act.. However, in 1976, the Hon. Desmond Guinness and the Irish Georgian Society intervened to save the house. Over the following 18 years the Society spent £500,000 on restoration, with the exception of the top floor. FAS , the State Training and Employment Authority, assisted during the final three years. In 1994 the Irish Georgian Society handed the house back to the Office of Public Works, who now run it together with the Park.

The landlord class, to which the St. Leger family belonged, is not generally remembered with affection in Ireland. Some landlords were more enlightened and humane than others, but they represented a social order in which land and wealth were the privelege of a very small minority. Without this system of privelege, Doneraile Park would never have been created. The landscape here would look very different if it had belonged to small or indeed large, farmers. Ironically, what was the loss of previous generations is the gain of this and succeeding ones. Man made landscapes are very fragile, much more susceptible to drastic change than buildings or towns.The conservation of this historic and beautiful landscape by the Forest and Wildlife Service means that now, and in the future, it can be enjoyed by everyone.

![]()

Click "Back" on your browser to return to the Index page.