Michael Flannery was born on a farm in Cangort, County Offaly (about a mile west of Shinrone, and not far from the Tipperary border), on 7th January 1903; the son of Andrew and Anne (née Quirke) Flannery; the second youngest of seven, with brothers Peter, Andrew and Joseph, and sisters Anne, Frances and Eileen. His father Andrew was born in Cangort on 12th August 1870; the son of Andrew and Fanny (née Larkin) Flannery - reputedly evicted from Youghalarra during the Great Famine.

Michael was educated at Mount St. Joseph’s, a Cistercian monastery school in nearby Roscrea, County Tipperary. He spent his teenage years during a particularly turbulent period of Ireland’s history. As a 14 year old boy, he joined his brother Peter in the Irish Volunteers around the time of the 1916 Easter Rising, and served as a messenger for his local battalion in the rebellion.

Michael’s career as a guerrilla fighter soon developed. After the second declaration of an Irish Republic on 21st January 1919, he lived on the run, rarely sleeping in the same place two nights in a row. By the age of 17, he was skilled in laying ambushes at lonely crossroads for the Black and Tans, and said he taught himself to kill "without regret and without bitterness".

"I felt angry but not bitterness towards them. I hated their actions but always said ‘God have mercy on your soul’ as they died."

He fought in the War of Independence (1919 - 1921) as a member of the Old I.R.A. in the flying columns (Tipperary No. 1 Brigade). A former colleague, Jack Moloney, recalled that ...

"Mike was cool as a cucumber under fire. He had brains to burn, and he never got angry. You couldn’t shake him."

He subsequently fought for the Anti-Treaty faction in the Irish Civil War (1922 - 1923). On the 11th November 1922, Michael was captured by Free State soldiers near Roscrea. He spent nearly a year and a half in Dublin’s Victorian Mountjoy Prison (C Wing) where he witnessed the execution of rebels Dick Barrett, Joe McKelvey, Liam Mellowes and Rory O'Connor in the courtyard through his cell window. His internment was interspersed with periods of solitary confinement and culminated in a 28 day hunger strike during which he was transferred to the Curragh of Kildare prison camp (Tintown camp #3, prisoner #886). He was eventually released on 1st May 1924, almost twelve months after the Civil War ended, and emigrated to U.S.A. a few years later, sailing from Cobh and arriving in New York on 14th February 1927.

He married Margaret Mary Egan in Rockville Center, New York in 1928, and settled in Jackson Heights, New York. Tipperary-born Margaret was a research chemist, educated at University College Dublin and University of Geneva. The couple had no children, but helped to raise and educate fourteen of their nephews and nieces both in Ireland and U.S.A.

He joined Sinn Fein, ancestor of the modern I.R.A. political wing, after the Fianna Fail Party was formed by Eamon de Valera. In 1927, Michael was dispatched by Sinn Fein to New York with his wife to organise opponents of the 1922 treaty. The Depression rapidly shifted his attention from politics to poverty. As his passions cooled, so did his ability to organise anti-government support. His campaign collapsed in 1933, after the Irish government established pensions for I.R.A. veterans.

Michael worked for 40 years in the actuarial department of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in New York City. Throughout his life, he maintained a keen interest in Irish affairs and was a member of numerous Irish-American social clubs.

In 1969, renewed fighting in Northern Ireland brought the recently retired veteran back into political action. He formed the Congress for Irish Freedom, and then the New York-based Irish Northern Aid Committee (nicknamed Noraid). Noraid is a non-profit, humanitarian organisation which raises funds for the families of Irish political prisoners in British, Irish and American jails.

In 1982, Michael and four other Noraid officials (Thomas Falvey, Daniel Gormley, George Harrison and Patrick Mullin) were charged in New York of gun-running to the I.R.A., but were subsequently acquitted. The trial of the "Brooklyn Five" ran from 23rd September to 5th November, during which the defence reportedly asserted that the men were acting at the behest of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Michael was well known for his support of the Republican Nationalist paramilitary struggle in Northern Ireland, consequently his election by the Ancient Order of Hibernians as Grand Marshal of the 1983 St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York divided Irish-American loyalties to the festivities. In context, this was a highly emotive period, following the relatively recent deaths of I.R.A. hunger strikers in H Block. The parade witnessed an unprecedented controversy when a number of civil and clerical dignitaries declined to take their normal places in the celebration. Ironically, their intended snub backfired by creating media interest and valuable publicity for the Grand Marshall’s cause. In his own words ...

"They have handed us the best propaganda opportunity we could have hoped for. You couldn’t buy this kind of publicity."

He died in New York on 30th September 1994 and is buried in Mount Saint Mary's Cemetery in Flushing, New York. His wife Margaret (known as "Pearl") died on 12th November 1991.

The National Irish Freedom Committee (Cumann Na Saoirse Náisiúnta), which Michael co-founded in 1987, hold an annual testimonial awards dinner in Astoria, New York every spring at which the Michael Flannery Spirit of Freedom Award and the Pearl Flannery Humanities Award are presented.

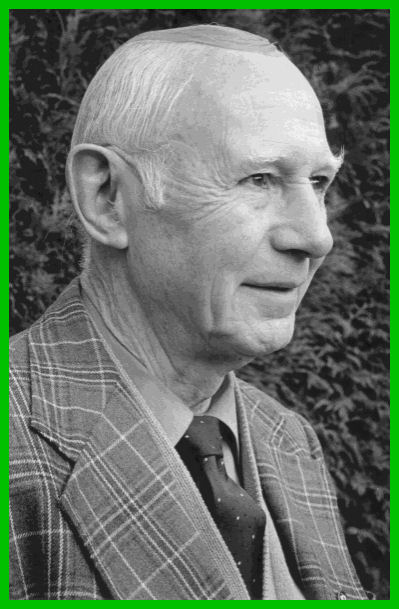

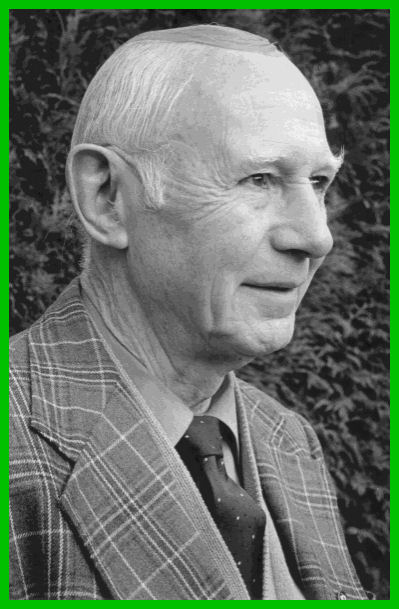

[portrait circa 1921 (left) courtesy of his biography "Accepting the challenge" edited by Dermot O'Reilly; War of Independence Service Medal and 50th Anniversary Medal ("Survivor's Medal"); portrait circa 1985 (right) courtesy of Pádraig Ó Flannabhra F.I.P.P.A.]