Harondor

~The Strategic Role

of South GondoR~

This essay examines the region of Harondor and its role within the

realm of Gondor. By the end of the Third Age, South Gondor had become “a desert and debateable land”, contested

between the Stewards of Gondor and the Corsairs of Umbar. Like other parts of

the realm that had been given up or overrun, its inhospitable state at the time

of the War of the Ring does not reveal the full history of the region. The

reoccurring theme though is the influence on its history of external powers,

principally Umbar, Harad and Gondor, and the strategic value of this region in

the contests between them.

Geography

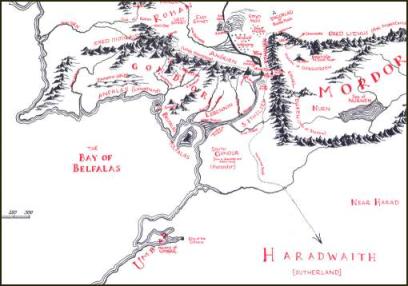

Harondor marked the border between two distinct regions of Middle

Earth, the Westlands and Harad. Geographically it was sizeable area, measuring

some 230 miles north to south and 400 miles east to west at its widest, and was

thus close in size to Calenardhon. It

was bounded by the Bay of Belfalas to the west, the Ephel Duath on the north

east and in the north and south by two major rivers, the Poros and the Harnen.

From our knowledge of the neighbouring lands of Ithilien, Mordor and Harad, we

can speculate that its land were fertile, at least along its coast and water

courses. The area of land that was desert or hills or woodland it hard to

guess. The route of the Harad Road would suggest some sort of physical

difficult ground in the centre (the foothills of the Ephel Duath perhaps), as

the road makes a wide turn to the southwest after the Poros crossing before

going south and eventually turning back southeast for the crossing of the

Harnen. On one map of the region circa 3017 TA, the cartographer

has described it as a “Desert and debateable land” ~ but I believe this was

meant in terms of Gondorian authority, rather than its geography.

Population

Apart from the fisher folk of the Ethir Anduin dwelling on its north

west shores, we must speculate about the Mannish inhabitants of the region.

Ethnically I would imagine Harondor had the normal Gondorian mix of

Dunedain and natives, but whereas the

native folk of the realm were heavily Dunlending, in Harondor they would have

been predominantly from Harad, the Anduin acting as a natural barrier to the

heavy settlement of this region by northerners. They thus added a Southron

strain to the cultural mix of Gondor (which contained Dunedain, Dunlendings,

and Northmen). Their loyalty may have varied based on the power of Gondor to

control and protect the region, and though the populace would have suffered

from occupation and wars waged over it, some elements of the population

probably felt more akin to the Haradrim invaders. We might even pose the

question, culturally was this South Gondor or North

Harad?

In terms of Dunedain settlement, while the Southern Dunedain

historically did maintain military and communication posts on their western and

northern borders, in the wide lands of Calendnardhon and Enedwaith, they did

not settle heavily in either of these frontier regions and their settlement

pattern in Harondor may have been similar.

Early History

Only the barest outline may be guessed of this land’s history before

the Third Age. It was inevitably an area for migration or trade between

Haradwaith and the lands around Ered Nimrais (in so far as the River Anduin

could be crossed). In the Second Age the societies and kingdoms of this area

experienced the intrusion of external powers, as it fell under the sway of the

Shadow of Mordor and later, the might of Numenor.

We can speculate that as the Numenoreans established strongholds close

by at Pelagir and further southward at Umbar, the native folk of this region

were influenced by the Numenoreans (for example by trade and the learning of

the Common Speech for use in external dealings). However, in time this contact

became aggressive and the region peoples had to acknowledge the sway of

Numenor:

“At first the Numenoreans had come to Middle-Earth as

teachers and friends; but now their havens became fortresses, holding wide

coastlands in subjection.” (LOTR App. A (i), p. 1012)

The proximity of two Numenorean bases, at Pelagir, a port of the

Faithful, and Umbar, a fortress of the King’s Men, would have allowed the Numenoreans

to exercise a hegemony over the surrounding coastland. As the more powerful and

aggressive of the two havens, Umbar would have been more prominent in this role

and would have retained any such control that survived the Fall of Numenor.

The Sea-King’s of Gondor 800-1150 T.A

The early Kingdom of Gondor was centred on the River Anduin and

included the port of Pelagir. Harondor lay outside the bounds of the realm

until sometime after 850 T.A, though settlements may have been established

along its northern river and coastal edges before this time. We can determine

the period in which the region was incorporated into the realm from a comment

on the reign of King Tarannon:

“With Tarannon the twelfth king began the line of the

Ship-kings, who built navies and extended the sway of Gondor along the coasts

west and south of the Mouths of Anduin.” (LOTR App. A (iv), p. 1020)

Harondor had been incorporated into the realm at the latest by the end

of the reign of King Hyarmendacil

(1015-1149 T.A), under whom the extent of Gondor’s territory reached its

apex. During his reign the southern

borders of the realm extended

“…south to the River Harnen, and thence along the coast to

the peninsula and haven of Umbar.” (LOTR App. A (iv), p. 1021)

The military role of the region is demonstrated by Hyarmendacil’s great

victory of 1050 over the kings of Harad. The chroniclers report that

Hyarmendacil brought his forces

“…down from the north by sea and by land, and crossing the

River Harnen his armies utterly defeated the Men of Harad.”

(LOTR App. A

(iv), p. 1020).

From this can be deduced that South Gondor was used as the staging area

for Gondor’s army in this campaign and that its harbours and roads were used to

facilitate the transportation of the army to the area.

Crucially, Gondor captured the Havens of Umbar in 933 T.A and managed

to hold onto it, despite strong efforts by the Haradrim to recover it. Control

of Umbar heightened the need to control Harondor, as it offered harbourage and

navigational aid for the navy and allowed quicker overland operations against

any force threatening the Havens. Possession of Umbar in turn made control of

Harondor easier, by securing its coasts from local raids or sea-borne invasion.

In terms of Gondor’s territorial expansion, why stop at the River

Harnen when so much territory lay beyond? Because with its coastal, mountain

and river borders it offered a more readily defendable marchland than the

territory south of the River Harnen. South Gondor’s value was as a buffer

between the hostile southlands and the heartland of the realm. It was used to

aid communication with Umbar, with lighthouses, ports, and watch-posts (similar

to those employed in on the northwest borders of Gondor) and as a belt of land

to be denied to hostile forces. Best to contest invasion on its distant borders

than to have to mount a defence in South Ithilien against an enemy already

crossing the Poros. This would have been the ideal in the minds of her kings

and councillors. But Gondor was not always capable of controlling this region

and in those times it did indeed provide a staging area for attacks on the

realm.

Harondor and the Crown

An interesting question is that of the political standing of the

region. Who ruled it for Gondor? Was it a fiefdom ruled by one or more local

families owing loyalty and service to the Crown? Did its military value mean

that it fell under the authority of one of the realm’s military captaincies

(e.g the Captain of the Fleets)? Or as a border region with military functions,

was it entrusted to a marchwarden? Fiefs tended to have strong populance, loyal

to Gondor, with military matters handled by local lords (e.g Lebennin,

Morthond, or Lossarnach); marchlands were on the borders of the realm, with

hostile or alien folk on or within its borders, thinly settled, with direct royal

involvement in defence via wardens (see the role of wardens at Angrenost and

Aglarond, and in Fourth Age Ithilien [Letter 244]). Harondor may have grown in

political stature into a fief and then, as it became a less secure possession, regressed to being a

marchland. Considering the size of the territory it probably had several lords

or royal officers governing different areas, ports, and fortresses, though

perhaps with one directly responsible to the Crown.

Military Defences

The Harad Road was an important overland trade route. It was also used

to speed the armed hosts of Gondor. Were forts maintained from which royal

soldiers could patrol against raiding parties, and escort incoming and outgoing

trade caravans? The existence of such forts would be consistent with Gondorian

military practise (such as the defences that guarded the Gap of Rohan, or the

northern crossings of the Anduin or the passes of Mordor). The same forts

probably witnessed a varied history of occupation, capture, destruction, rebuilding

or abandonment as Gondor battled its enemies for dominance.

The Regional Geography of South Gondor

Southern Hostilities 1448-3017 T.A

The region prospered from the coastal and overland trade going to and

from the south via Umbar and the Harad Road. However, when the nature of

relationship between Gondor and Harad became darkened by agents of the Shadow,

then hatred and the quest for dominance weakened considerations of trade or

contact.

The Kin-strife (1432-48 T.A) was to have a major consequences for the

region. South Gondor was most likely aligned with the southern, sea-faring

factions supporting Castamir. Following Eldacar’s recapture of his throne, the

rebels, as is well known, seized the havens of Umbar and became perpetual

enemies of the rulers of Gondor. They proved a deadly peril to the commerce and

coasts of Gondor. The peril was especially felt in Harondor because of the

proximity of Umbar. It is possible that in the immediate aftermath of the

civil-war, the corsairs enjoyed some local support on the coasts of Harondor.

However, the vicious nature of the conflict between the Corsairs of Umbar and

the Crown proved especially devastating for Harondor, with towns sacked,

villages burned, and merchant ships captured. The people of the region relied

on periods when the Corsairs were

subdued or the Gondorian navy was strong enough to protect the coasts. From

this point on (1448 T.A) it is recorded that:

“…the region of South Gondor became a debatable land between

the Corsairs and the Kings.” (LOTR APP. A (iv), p. 1023)

From this we can understand that Harondor suffered an insecure

situation within the realm of Gondor as control of its territory and coasts

forcefully shifted between Umbar and Gondor.

Some major examples of the changing balance of power in the region are contained in the surviving records. The forces of Harad swept across the Poros in the invasion of 1944, suggesting that the Crown allowed them to overrun South Gondor as it could only offer resistance in the closer and narrower terrain of South Ithilien. So by 1944 at the latest, the region has become seriously exposed to threats, both by sea and land. Gondor still managed to contest for control of the region in the centuries that followed. Much later, in the stewardship of Turin II, we read of the occupation of South Gondor by the Haradrim. Though the subsequent victory of Gondor in 2885 may have brought a respite it is not stated if the Haradrim were fully driven out of Harondor.

It is instructive at this point to examine the fate of the neighbouring region of Ithilien, where the forces of Gondor battled the renewed power of Mordor from 2000 T.A. Gondor was unable to prevent the infiltration of that land by Mordor’s forces and this resulted in the gradual flight of the people of Gondor from the province. Eventually the land was dominated by Mordor and Gondor’s presence was limited to military outposts and patrols. The same fate was suffered by Harondor. Efforts to control the territory were doubtless hastened by the decline of Ithilien into an orc-infested marchland. By the time of the War of the Ring, Gondor still controlled the northwest shores of Harondor and probably maintained ships, scouts and outposts for forewarning of enemy movements, but it could not hinder the passage of enemy forces through Harondor on their way to serve Mordor.

End Note

In the Fourth Age, after War of the Ring and the defeat of Mordor, the

rebuilding of the realm of Gondor would doubtless involve it once again in

efforts to protect its coasts and lands from the Corsairs and the Haradrim. In

time, the King’s banner would once again fly above the Crossing of the Harnen

and the region of South Gondor would resume its historical role as a military

and cultural marchland between Gondor and Haradwaith.