|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

The patterns of settlement in Early Christian County Down

Chi-squared values, up to 1km radius: CORINE map

Individual values become significant at 3.8 Overall chi-squared vales become significant at 16.92 quite often formed by scarping a natural hillslope their predominance in the drumlin areas is not surprising. By comparing the results of platform raths and raised raths with those of mounds it was hoped to identify if these could be potential Early Christian settlement sites. Unfortunately the results for the mounds are very mixed, showing no definite correlations with either site type, and not helping with the interpretation of these sites. Some of the more unusual results are provided by the raised raths. Within the 1km radius catchment area for these sites there are significantly higher than expected quantities of the type 8 (ABE/BP) soil. This is the best quality soil within County Down, suitable for arable farming. The results from the Land Classification map are similar, with higher than expected quantities of the best quality, grade A and A/B1 land and although there are no significant results noted in the CORINE analysis, it seems likely that these raised raths were carefully located for access to the best quality, arable land. There is a cluster of raised raths found in the Lecale area, which, as discussed above, is favoured by ecclesiastical sites and avoided by most other rath types. Both these factors suggest that raised raths are somewhat different from the more common rath types, and supports the suggestion by both Avery (1991, 125) and Mytum (1992, 126) that these are high status sites. If these potential high status sites are located on good quality ground then we might expect the same for bivallate and multivallate raths. The soil map suggests that bivallate raths are concentrated in the drumlin belt and located on average quality soils. However, the Land Classification map indicated that within the catchment areas of bivallate raths there are significantly high proportions of the best quality, grade A land – similar to both the raised raths and pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites. This is supported by the CORINE results which show significantly high quantities of agricultural land within the catchment area and significantly low proportions of poor pasture. Overall the results tend to indicate that while bivallate raths are located in similar areas to univallate raths, they tend to have a higher quality of ground within their catchment areas, more suitable for arable use. Multivallate raths are considered to be the highest status sites, the residence’s of kings, but the site catchment results from all three base maps indicate that the land surrounding these settlements is fairly mediocre and not of the particularly good quality that we might have expected. It is clear that these multivallate raths were not being located close to the best quality land and other factors must have dictated where to settle. If these are indeed the settlements of the highest ranks of Early Christian society, then perhaps a strategic location was more important. Crannogs also appear to be located in areas of rather mediocre quality land. The site catchment analysis of the Soil map demonstrates that these sites have higher than expected quantities of type 19 (ABE/gley) soil within the areas. The results from the Land Classification map are very similar, displaying significantly high proportions of the B3 grade of land. Crannogs are also the only site type not to have significantly low proportions of the D category of land. Again the CORINE results are similar. Although there are no significant values in the catchment area, this in itself is unusual, making crannogs one of only two site types not to have a significantly low proportion of scrub in this catchment zone, the other being cashels. It has been suggested that crannogs are important royal settlements, although Warner (1994, 61 – 69) has suggested that rather than being the main royal dwelling, they were secondary sites, perhaps used as a bolt-hole or a politically strategic fortification, and a defensive location may well have outweighed any other consideration. The site catchment analysis results for the large raths show significantly high proportions of ground suitable for pasture and significantly low proportions suitable for arable use. This may suggest that the large size of these sites is related to a predominance of pastoral farming. The early literature describes the practice of driving cattle into the raths at night for protection against raiding (McCormick 1995, 33 – 37). If the occupants of these sites required access to only very small quantities of arable land, then it seems reasonable to presume that they had larger herds of animals than the usual farmer, perhaps explaining the larger size of rath, required for corralling them when necessary? The results of the site catchment analysis for the large enclosures also shows them to have significantly high proportions of the pasture land of the drumlin belt within the catchment zones. On the Soil map this can be seen as high chi-squared values for the type 19 (ABE/gley) soil. The analysis on the Land Classification map produces higher than expected values for the lower-medium quality B3 classification and on the CORINE map the good pasture category also has higher than expected. These large enclosures are located on very much average quality pasture land, dispersed amongst the raths of the drumlin belt. Rath pairs also tend to be located in areas of average quality land, more suited for use as pasture, perhaps supporting suggestions that rath pairs were built for corralling cattle. We may expect similar results for conjoined raths, but in fact the results suggest that they were located with access to better quality land, with higher than expected proportions of both the type 6 (ABE/SBP) soil and agricultural categories within the catchment areas, making these sites difficult to interpret. Raths with souterrains were examined as a separate category from raths to attempt to identify any difference in their locations. Unfortunately the results for these sites are somewhat contradictory. On the Soil map and CORINE maps the catchment areas contain significantly higher than expected proportions of the best quality ground, but surprisingly, the Land Classification analyses indicate significantly high proportions of the lower-medium quality, B4, grade of land. This discrepancy is caused by the fact that raths with souterrains are concentrated in the zone between the Mournes and Slieve Croob, which has been designated as very different quality on the Land Classification map as compared to the Soil and CORINE maps. If we accept the soil and CORINE map results and compare these raths to those without souterrains, it appears that raths with a souterrain are located in better quality areas, which may suggest that it was the farmers living on the better quality land who built souterrains. The results of their site catchment analysis for isolated souterrains are also somewhat contradictory, with high proportions of good quality land within their catchment areas, but also high proportions of poor quality ground. The results for these isolated souterrains show certain similarities to those of raths with souterrains, and it seems sensible to assume that there were settlements associated with them, which were willing to put up with some lower quality ground in the surrounding area in order to get access to some of the best quality. Perhaps we should have some concerns about this distribution pattern, however, if we consider that most souterrains are found in the course of modern ploughing. It would be these better quality soils which would be most likely to be regularly ploughed, and what we may in fact be seeing is a result skewed by modern ploughing patterns. Unsurprisingly the site catchment analysis results for the Land Classification and CORINE maps indicate that cashels have significantly high proportions of the poorest quality land with their catchment areas – more so than any of the other site types. However, the soil maps contradicts this, indicating high quantities of the best quality type 8 (ABE/BP) soil within the catchment areas. The vast majority of cashels are located in the areas of the Mournes and Slieve Croob and perhaps while the soil in this area may be good quality, other factors mean that its use is severely restricted. If we assume that cashels are the stone equivalent of raths then we must wonder why Early Christian farmers would have located their settlements in such poor areas, particularly when there are sparsely populated areas of good quality land to the east. Perhaps some of these cashels are strategic sites, or there may have been social reasons for their location, which are not evident in the archaeological record. The results for the site catchment analysis of the three groups of ecclesiastical sites are interesting. The pre-Viking ecclesiastical sites are located on moderate – quite good quality land. Surprisingly, the only significant result on the CORINE analysis is in the artificial category, indicating that many of these pre-Viking sites are now in urban areas. By contrast it is immediately obvious from the site catchment results that the pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites are located on some of the best quality ground. Within the catchment areas there are significantly higher than expected quantities of the high quality, type 8 (ABE/BP) soil and of the grade A land on the Land Classification map. Similar results are found on the CORINE map for the high quality agricultural category. Overall there is a substantial improvement in the land quality compared to that of the pre-Viking sites. During the eighth century both the jurisdiction and income of the church increased enormously and as nobles began to not only found ecclesiastical sites, but also join the monasteries in the powerful position of abbot, it is perhaps not surprising that we can see the church moving onto better quality, arable land. The results of the catchment analysis for the probably pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites are quite similar to those of the known pre-Norman sites suggesting that these may well also be pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites.

Conclusions on the site catchment analysis results While the site catchment analysis technique does not produce clear-cut results which aid in the interpretation of every site type, it has proved useful. The above results indicate that raths are located on average quality land while both bivallate and raised rath sites are located with high proportions of the best quality, arable land within their catchment areas, supporting the suggestion that these are high status settlements. Surprisingly the land surrounding the multivallate raths is not of a particularly high quality and for these sites, as with crannogs, we may have to consider that other, strategic or political factors, were dictating their location. The overwhelmingly poor catchment results for cashels suggests that we should consider that at least some of these sites may also have been located for strategic purposes. Rather surprisingly, it appears that those raths with souterrains and the apparently isolated souterrains are located on better than average quality land. However, there is no doubting the results of the site catchment analysis for the ecclesiastical sites. From the rather average quality land of the pre-Viking settlements, there is a vast improvement in the pre-Norman period, reflecting the rise in the power and wealth of the church described in early literature. A number of trends can also be seen in these site catchment results. Almost all site types consistently avoid the poorest quality land, as we would have expected from a farming community. Generally it is the average quality categories, i.e. the type 19 (ABE/gley) soil and B3 land classification which consistently achieve significantly higher than expected results. This indicates the concentration of Early Christian sites within the drumlin areas, although the better quality type 8 (ABE/BP) soil and A and A/B Land Classification categories of the rolling lowlands, also produce a reasonable number of higher than expected results. Overall, however, this has proved a useful analysis technique, providing a further insight into those factors which influenced settlement location during the Early Christian period.

Thiessen polygons: theory, approach and problems Thiessen polygons are constructed by drawing perpendiculars through the mid-points of neighbouring sites; every point within the created polygon is therefore closer to the site it encloses than to any other site. In this study the Thiessen polygons serve two purposes. In the first instance they provide us with information on the size of the possible territories surrounding each site type. This allows us to compare, for example, the size of the Thiessen polygons surrounding raths with those of bivallate or multivallate raths. The second purpose of this analysis is that the Thiessen polygon layer can be overlaid onto each of the three basemaps – the Soil map, Land Classification map, and CORINE map, allowing us to look at the quality of land within the polygons of each site type. Thiessen polygons assume that all sites within the study area were occupied simultaneously. This is obviously impossible to know for certain, but Stout (1997, 24–29) and Lynn (1994, 81-94) both conclude that the main period of construction and occupation of raths was in the three hundred years between the seventh and ninth centuries, suggesting that many of them probably were contemporary.

The average area of Thiessen polygons The results in Table 33 show the average size of the Thiessen polygons surrounding each site type. The average size of Thiessen polygons surrounding each site type

From this table we can see that raths have fairly moderate sized polygons at 1.4 km2, the same as bivallate raths. Perhaps the most surprising result is that of the multivallate raths which is the smallest of any site type at just 0.7 km2, half the area of the average Thiessen polygon of a univallate or bivallate rath. Does this suggest that the occupants of these sites were of such high status that they did not need to farm a large area of land around their settlement, but could rely on tribute and returns from clientship agreements instead? Platform raths and raised raths both have a fairly large average size of Thiessen polygon at 2 km2 and 2.2 km2 respectively. We must consider if the large area of these Thiessen polygons supports Avery’s (1991) suggestion that the height of these raised and platform raths reflects their high status. These Thiessen polygons are larger than those of univallate, bivallate or multivallate raths, but we must also take the quality of the land within these areas into consideration. Mounds have a much larger average size of polygon at 2.7 km2, the largest of all the domestic settlement sites. As this result is considerably larger than that of either the raised raths or platform raths it is difficult to classify these mounds as disturbed rath sites. Perhaps surprisingly, large raths have quite a small average size of Thiessen polygon, at 1.2 km2, considerably smaller than that of ordinary raths. By contrast, large enclosures have a reasonably large average size of polygon at 1.7 km2. If, as has been suggested, these large enclosures were gathering points for the local community or tuath, for stock counting etc. they would not need a particularly large territory. Both these large enclosures and large raths remain difficult to interpret. Also difficult to interpret are the conjoined raths. These sites have a very small average size of Thiessen polygon at just 1 km2. Rath pairs have a similarly small average area at just 1.2 km2. It has been suggested that one of the raths in a pair or conjoined group was used for corralling stock. If this is the case then we may assume that these farmers had a very high number of cattle to be able to afford and need to build a separate enclosure for them. However, would someone with a large number of stock have the smallest size of territory of any of the settlement types? Even without the need to grow crops, surely this is a very small area in which to keep a large herd of cattle. The results for the conjoined raths and rath pairs therefore may contradict the suggested explanations for these sites. Raths with souterrains have an average Thiessen polygon size of 1.4 km2, very similar to that of raths without associated souterrains. By contrast the average size of polygon of isolated souterrains is 2.1 km2. This is much larger than that of either raths or raths with souterrains. Perhaps these souterrains were built by a group of families living in unenclosed settlements, thereby explaining the larger polygons of this site type? If, however, these are the remains of later settlements built outside raths by those who originally lived in them, as suggested by Lynn (1994), then we may be again be surprised that the territory is so much larger than that of raths. The problem with isolated souterrains of course, is that we may be seeing only a small percentage of the true number of sites. The majority of unenclosed souterrains are revealed as a result of ploughing, and what we may actually be seeing in their distribution is a reflection of modern ploughing patterns, rather than the true distribution. There may in fact be many more unenclosed souterrains in County Down, and this would effect the overall pattern and size of the Thiessen polygons of all the sites. However, we can only work with the material currently available, while bearing this problem in mind. The average size of the Thiessen polygons for both cashels and crannogs is very large at 2.5 km2 and 2.7 km2 respectively. These territories are large because they encompass large tracts of the uplands where there are no other settlements. While these uplands may have been used for summer grazing this is not taken into consideration in the Thiessen polygon analysis. The average size of Thiessen polygon for all three types of ecclesiastical site is very large. It is noticeable however, that the pre-Norman and probably pre-Norman polygons are both slightly larger than those of the pre-Viking sites. The fact that the probably pre-Norman sites have a similar average size of Thiessen polygon as the known pre-Norman sites suggests that these may be pre-Norman ecclesiastical sites, although this is something which is looked at in more detail below. The fact that all of these ecclesiastical sites have large territories indicates the importance and power of the church during the Early Christian period. These results show us very clearly that we cannot simply rely on the size of the Thiessen polygon as an indication of the status of a site. The quality of the land within these Thiessen polygons is looked at below, to give us a further understanding of the settlement patterns of each site type.

Thiessen polygon analysis on the basemaps The Thiessen polygons were overlaid onto each of the base maps and the results can be seen in Tables 34 – 36, and the results from applying a chi-squared test to these can be found in Tables 37 – 39 below. Again this has been used to determine any statistically significant associations, and those results which are higher than expected are highlighted in red, while those which are lower are highlighted in blue.

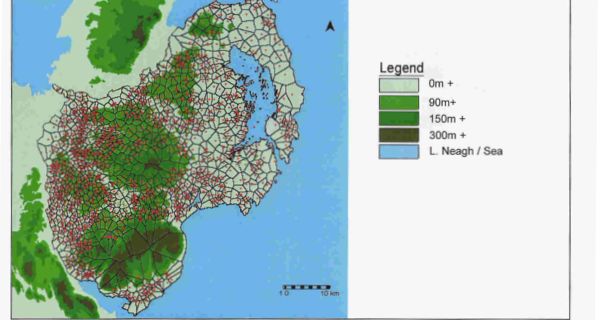

Thiessen polygons on the contour map

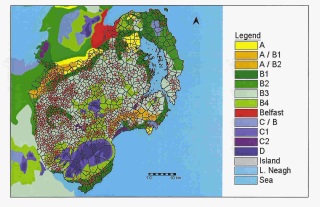

Thiesses polygons on the Soil map Figure 22 Thiessen polygons on the Land Classification Map

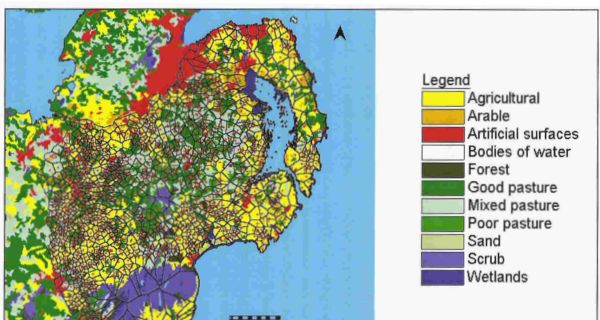

Thiessen polygons on the CORINE map

Thiessen polygon results based on the Soil map

Results are shown as a percentage of the total area covered by each site type

Results are shown as a percentage of the total area covered by each site type

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||