Chapter 5

In this chapter I will take a kaleidoscopic look at Bartók’s mature compositions. The purpose of the discussion will be to show how Bartók continued to be influenced by elements originating from his experience of folk music. I shall examine these influences, which continued to permeate his musical language through to the very end of his life, showing how Bartók expanded his ideas of arrangement to the point where he assimilated folk music into more large-scale and sustained forms.

In the years 1918-1920, Bartók embarked on what Malcolm Gillies calls “his most radical, Expressionist phase, during which he believed he was approaching some kind of atonal goal.”[1] In the essay “The Problem of the New Music” (1920), Bartók charted the development of atonal music leading up to the developments of the dodecaphonic method. Bartók’s comments indicate that he was greatly influenced by the equalisation of the chromatic scale.

The possibilities of expression are increased in great measure, incalculable as yet, by the free and equal treatment of the twelve tones.[2]

Bartók gave examples of adjacent dissonant note sonorities, suggesting a more varied approach to atonality than the dodecaphonic methods of his Viennese colleague Arnold Schoenberg. He proposed the retention of certain features of the tonal system such as triads and scale constructions. As isolated occurrences they do not infer a sense of tonality. The most obvious musical parallel to these ideas was Bartók’s The Three Studies, op. 18 (1918) for piano, which is undoubtedly one of Bartók’s most radical creations. Paul Wilson points out that the products of this period (The Miraculous Mandarin op. 19 (1918-19) and the First and Second Violin Sonatas (1921 and 1922) “employ a harmonic language which greatly modifies and often abandons the modal and polymodal basis of Bartók’s previous and subsequent works.”[3]

Bartók’s Improvisations for Piano, op 20 (1920) are generally paired with The Three Studies, linking his ideas of folk music arrangement with atonal tendencies of this period. In his Harvard lectures Bartók commented on this work:

In my Eight Improvisations for Piano I reached, I believe, the extreme limit in adding most daring accompaniments to simple folk tunes.[4]

Paul Griffiths points out that it was with the improvisations that “the distinction between arrangement and original composition is beginning to break down.”[5] Bartok introduced a method, involving the treatment of folk tunes as “mottos,” which are repeated against different accompanimental backgrounds. In his , “The Influence of Peasant Music on Modern Music” (1931), Bartók contrasts this way of working with the techniques utilised in his earlier folk arrangements (1907-18).

In one case accompaniment, introductory and concluding phrases are of secondary importance, and they only serve as an ornamental setting for the precious stone: the peasant melody. It is the other way round in the second case: the melody serves as a ‘motto’ while that which is built around is of real importance.[6]

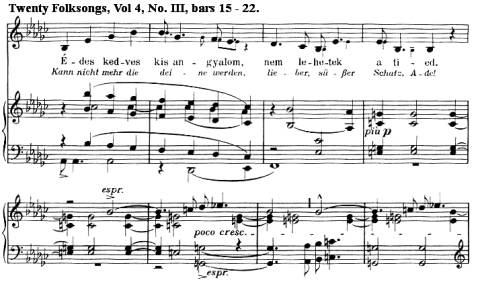

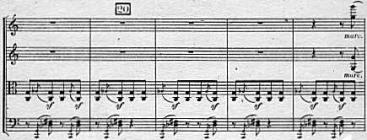

Bartok used the following example from his third improvisation (bars 16-30) to illustrate this point. The folk melody appears in the lower stave (bar 19) set against a dense accompanimental texture (Ex. 5.1).

Ex. 5.1: Improvisations op. 20, no. 3, bars 16-30.

Bartok distanced himself from the more restrictive dimensions of folk music by trying to overcome what Schoenberg called “the discrepancy between the requirements of larger forms and the simple construction of folk tunes.”[7] This is achieved in the Improvisations for Piano, op. 20, by synthesis of folk music material into more expansive formal plans. Paul Wilson points out that the eight movements can be grouped together in four units:[8]

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Nos.

1-2 |

Nos.

3-5 |

No.

6 |

Nos.

7-8 |

| |

Modal

final: G |

Scherzo

like. |

Modal

Final: C |

Wilson shows that the first piece of each section begins with a setting that is closely derived from the folk tune.[9] He describes how the opening bar of the first improvisation contains a melodic interval of a major second (F-Eb), which dominates the accompanimental texture of the following bars. The derivation of vertical harmonic structures from melodic line is utilised as a method of motivic integration. At the ends of each of the sections outlined by Wilson this integration is abandoned in favour of a freer accompanimental technique. With the exception of no. 6, the tempo for each section progresses from fast to slow. The common final notes of G and C link the pieces 3-5 and 7-8 respectively. These important links between musical events show that Bartók was thinking of a more expansive structural coherence, a feature that was entirely absent from his earlier collections.

A similar approach is adopted in Village Scenes for Voice and Piano (1924), which is a five-movement setting of Slovak ceremonial songs. Vera Lampert points out in these songs represent Bartok’s second category of arrangment: “the original melodies submit themselves to the logic of the composition.”[10] Again Bartók uses a “motto” like procedure to develop the accompanimental material, achieving a balance between voice and piano. Similarly to the Improvisations Bartok exhibits the tendency to combine folk melodies within a larger framework, circumventing the formal restrictions of the medium. Vera Lampert writes:

In the third and fourth movements Bartók experimented with expanding the formal possibilities in the folk song arrangement, taking two folk melodies as the basis of a single movement and organising them into simple classical forms.[11]

This can be demonstrated by tabulating movement three and four, which reveal Bartók’s use of simple classical forms such as Rondo and Ternary.

| Movement |

Form |

Tabulation |

| 3:Wedding Songs | Rondo with piano interludes | XAxBxAxBABx |

| 4: Lullaby | Ternary | AABBBA |

This tendency towards structural synthesis of folk tunes is not so apparent in Bartók’s last collection of folk settings for voice and piano. The collection, Twenty Folksongs for Voice and Piano (1929), is grouped into four volumes entitled: Sad Songs, Dancing Songs, Diverse Songs, and New Style Songs. Unlike Village Scenes, the folk songs are presented as self-contained entities, grouped together in one big cyclical creation. Rather than being a fusion of different melodies, form is extended by repetition, and in some cases up to six stanzas are used. Variation in the accompanimental texture is maintained with a system of through-composition, which is used consistently. Lampert points out the importance of Bartók’s creation:

With the Twenty Hungarian Folksongs of 1929 the emancipation of the folksong arrangement within the realm of original composition had reached a new stage.[12]

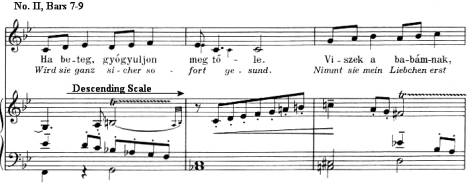

Bartok deviated from all of his previous methods of folk arrangement, but like the Improvisations, op. 20, he established a fixed point of reference with his use of the “motto” function. The aim to incorporate folk music into a larger structural framework can be demonstrated by the structural continuity of accompanimental texture, which is maintained throughout this collection. An example of this can be found in the final volume of songs, where Bartók uses a motivic link (a descending, and sometimes ascending scale) to accentuate the cyclical unity of the group (Ex. 5.2). Rachel Beckles Willson writes:

Sketches reveal that Bartók carefully reinforced the songs’ unity in this way. He revised the third central song to interpolate not only a piano interlude based on retrograde of the main scale passage of the melody, but also a descending scale passage over ten degrees in counterpoint with the voice’s preceding verse.[13]

Ex. 5.2: The scale motive in Twenty Folksongs, Vol. 4.

Twenty Folksongs for Voice and Piano could also be classified as art-music, as Bartok gives his accompaniment an expressive quality typical of a conventional song cycle. Griffiths points out the there is sometimes an apparent divergence between the melody and accompaniment. The tunes “are set in relief, by divergences of melody, harmony and rhythm.”[14] Other commentators such as Lambert have drawn attention to Bartók’s preoccupation with the linear counterpoint. Bartók, who had visited Italy in 1925 and 1926, had engrossed himself in Italian Baroque keyboard music. This influence is certainly of significance, as these works exhibit a much greater degree of horizontal counterpoint than is found in Bartók’s earlier arrangements. In Twenty Folksongs folk music and the linear counterpoint are inseparable, as they both become interrelated elements.

The Hungarian musicologist Bence Szabolcsi has drawn attention to an apparent conflict in Bartók’s work. He quotes a statement made by Bartok to Denjis Dille in 1937.

The ‘absolute’ musical forms serve as a basis for a freer musical formula even if these formulae involve characteristic melodic and rhythmic types. It is clear, however, that folk melodies are not really suited to be forms of ‘pure’ music, for they, especially in their original shaped do not yield to the elaboration which is usual in these forms. The melodic world of my string quartets does not differ from that of folk songs: it is only their setting that is stricter. It has probably been observed that I place much of the emphasis on the work of technical elaboration, that I do not like to repeat a musical thought unchanged, and I never repeat a detail unchanged. This practise of mine arises from my inclination for variation and for transforming themes […] the extreme variety that characterises our folk music, at the same time, a manifestation of my own nature.[15]

Based on the above quotation Szabolcsi describes an opposition of forces that is discernible in Bartók music. On one hand, the unconscious element, which is “an aspiration related to the ever-changing, shaping nature of folk music.” And on the other, the conscious element, which asserts itself as the requirement for a “strict framework, the tendency for concentration, for unity and distilling.”[16] Both of these forces act as counter weights and are constantly shaping each other.

After an initial phase of discovery (1907-1918), Bartók’s ethnomusicological work entered a period of analysis, which lasted to the very end of his life. Griffiths points out that during the period from 1904 to 1918, Bartók’s original music was at its most immediate and uncontrolled. As ethnomusicological activities became more analytic, his original music followed a similar path.[17] This constant reassessment of folk music sources made their grammar and syntax almost second nature to Bartók, and it is not surprising that out of this he formed a deeply intuitive level of compositional activity. The above statement reveals that, as an original composer, Bartók was influenced, not by only actual melodies, but by the inherent logic of folk music. He acknowledged the need to derive structures, by which to control these influences. Griffiths charts Bartók’s development as a composer as “first a period of close involvement and direct transcription, then a time of analysis and deeper creative connections.”[18]

To Bartók’s three categories of folk music arrangement (mentioned in chapter three), Benjamin Suchoff adds a further two levels of folk influence, which define his approach to free composition.

(4)

The composition is based on themes, which imitate genuine folk

tunes.

(5)

“Neither the folk tune is used, but the work is nevertheless

pervaded by the ‘spirit’ of folk music”[19]

Bartók makes a distinction between the macroscopic use of melody and the microscopic assimilation of techniques: “in my original works they [folk tunes] have never been used.” He goes on to say: “if there is no indication of origin, then there have been no folk melodies used at all.” The influence of folk music, Bartók states, “is largely a matter of intuitive feeling, based on some kind of experience of folk music material.”[20] In the vast majority of Bartók’s original compositions, folk music influences are of the later variety, adopting the spirit of the music rather than quoting tunes or deriving synthetic equivalents.

It will be my purpose in the remainder of this chapter to

look at some of the most obvious connections between folk music

and Bartók’s mature works. Each of these will be

listed according to separate categories.

Form

and Variation

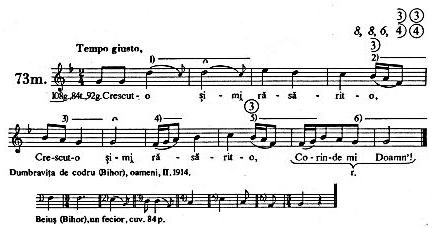

Bartók’s famous statement to Denjis Dille (see page 79), illustrates the importance he placed on the variational procedure, which he derived from folk music. Throughout his lifelong career as an ethnomusicologist, Bartók continually strove to improve his methods of transcribing, and after 1934 (the date of his appointment to the Academy of Sciences in Budapest) he was better able to notate the living form of folk music. These transcriptions demonstrate the tendency among performers of folk songs to alter musical material upon repetition. This process is largely intuitive and is expressed in several different ways. It could take the form of variation of a melody in successive verses of a song, or it may take the form of long-term change with the process of oral transmission generating variants of the same tune. In any case, variation is an intuitive instinct of the folk musician and an important means to express individuality in a collective musical expression. This point can be demonstrated with reference to a transcription of a Romanian melody Bartók collected in 1913 (Ex. 5.3).

Ex. 5.3: Bartók’s holograph of melody No. 79e from Vol. II (Vocal Melodies) of Bartok’s Romanian Folk Music (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1967). Reproduced in “Some Problems of Folk Music Research in East Europe” in BBE, pp. 174-175.

In each successive repetition of the tune, the performer varies the melismatic ornamentation of the basic melodic substructure. This process of transcription enabled the study and analysis of performance, which stimulated Bartók’s assimilation of a similar process into his own compositional idiom.

Paul Wilson demonstrates the use of the variation principle in Bartók’s Violin Sonatas. The first movement of Violin Sonata No. 1 (1921) uses sonata form, which is transformed by Bartók’s variational process. Wilson describes the rather unorthodox approach to the treatment of material in the development section:

Instead of a Beethovenian ‘working out’ of motifs, he makes the development a kind of meditative variation on the themes with some new material being added.[21]

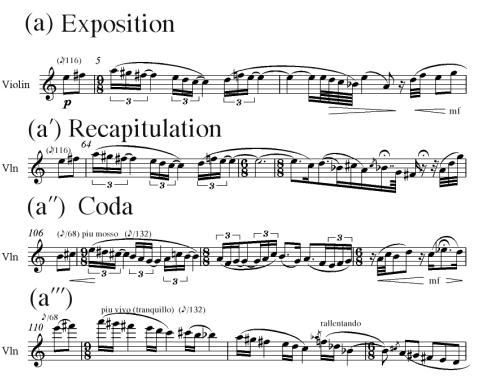

Wilson points out that the movement creates formal design in three parts, which one might tabulate as A A' A?.[22] This movement illustrates the combination of two basic formations of Bartók’s musical thought: form and variation (the combination of Szabolcsi’s conscious and unconscious elements). This point can be demonstrated with an examination of the different statements of the main theme (Ex. 5.4). The theme is initially stated in the exposition (bar 3) and reappears in altered forms in the development and recapitulation sections (bars 123 and 187 respectively). In addition to variational strategies like modifications of pitch and rhythm, Bartok also changes other musical parameters such as register, tempo, and dynamic. The theme is repeated, but only in a form that is varied, and in this way Bartók was able to re-invigorate his music in a manner that he associated with the natural purity of expression in folk music.

Ex. 5.4: First Violin Sonata, movement 1. Treatment of main theme.

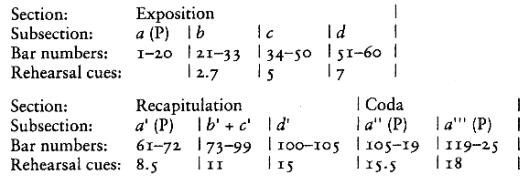

A similar manipulation of form occurs in the Violin Sonata No. 2 (1922). The first movement is comprised of an exposition and recapitulation of four themes. The layout of the work resembles sonata form without a development section.

In his discussion of the work, Wilson proposes the following formal analysis:

Ex. 5.5: Tabulation of the first movement of Violin Sonata No. 2.[23]

Bartók uses a process of variation to alter repetition of themes from exposition to recapitulation. The primary theme appears four times, and on each appearance it is varied according to a plan, which bares a strong resemblance to the variational procedure of folk music (Ex. 5.6). Peter Laki draws attention to the similarity of the main theme to the Romanian hora lunga, which has no fixed form and is improvisatory in character.[24] The ornamental writing and rhythmical freedom of the melodic line implies a sense of improvisatory performance, which is allied to folk music.

Ex. 5.6: Violin Sonata 2, Movement 1. Variations of main theme.

The variation principle can also be demonstrated in larger scale

works like the String Quartet No. 4 (1928). This

work is arranged using a symmetrical arch structure of five

movements (ABCBA). The work’s five movements correspond to

the character of the classical sonata form. Bartók uses an

extensive variation process, which had become second nature to

his music, within the movements and also between the various

paired sections of the overall arch form. The central

slow movement is the nucleus of the piece around which the other

movements are symmetrically arranged. The fourth movement

mirrors the second in free variation, and movements one and five

share the same thematic material. It was in this manner

that Bartók captured what he called the spirit or essence of

folk music..

Rhythm

In the Fourth String Quartet (1928) Bartók used a variety of rhythmic approaches, which were influenced by different folk music models. In the third movement, he used a free ornamental line set in the cello, against the motionless chords of the other instruments (Ex. 5.7).

Ex. 5.7: Fourth String Quartet, Movement 3, bars 7-12.

This melody demonstrates a rhythmical freedom that is achieved in many of Bartók’s works. Long notes, tied over the bar lines, are surrounded by small constellations of ornamental notes.

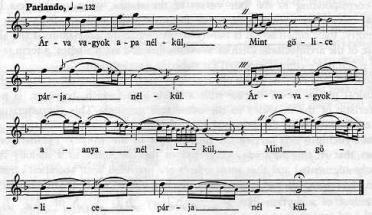

A probable influence was the rhythmically free “old

style,” parlando rubato tunes of the Hungarian

tradition. The following example demonstrates the

indeterminate rhythmical values that can be found in this form of

vocal rendition (Ex. 5.8)

Ex. 5.8: Example of old style folk tune[25]

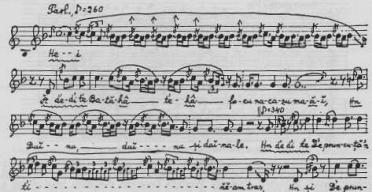

Variants of Romanian music, such as the hora lunga also made an impression on Bartók’s innate sense of irregular rhythm. Musicologists have shown many important comparisons between Bartok’s themes and the hora lunga. Bartok described the hora lunga and gave the following as an example (Ex. 95.9).

Its features are: strong instrumental character, very ornamented, and indeterminate content structure.[26]

Ex. 5.9: Section of a hora lunga melody transcribed by Bartók[27]

There is an obvious similarity between this type of melody and the third movement of the Fourth Quartet. At the point where the melodic line is transferred to the violin (bar 35), it adopts an improvised freedom similar to the feeling conveyed in the above transcription (Ex. 5.10).

Ex. 5.10: Fourth String Quartet, Movement 3, bars 35-40.

A different type of irregular rhythmic procedure can be found in the first and fifth movements of Bartók’s Fourth String Quartet. The rhythmic asymmetries contained in these movements share an affinity with Bartók’s experiences of Bulgarian rhythm. Timothy Rice describes how Bulgarian melody consists of “consistently repeated measures with two different durations in the relationship of 2 to 3.”[28] The adding together of the rhythmical values of two and three create what is commonly termed “additive rhythm.” This is usually notated in meters of irregular groupings of sixteenth notes.

In his essay “The So-called Bulgarian Rhythm” (1938), Bartok described the rhythmic diversity of Bulgarian meters:

It appears that the most frequent Bulgarian rhythms are as follows: 5/16 (subdivided into 3+2 or 2+3); 7/16 (2+2+3 – the rhythm of the well known Ruchenitza dance); 8/16 (3+2+3); 9/16 (2+2+2+3) and about sixteen other less common rhythmic types, not counting rhythmically fixed formulas (that is different patterns in alteration).[29]

In the same essay he demonstrated this point using the following melody (Ex. 5.11)[30]

Ex. 5.11: Section of a Bulgarian Dance for Violin

There is an obvious similarity with the irregular rhythmic groupings of the first movement of the Fourth Quartet. In the following example Bartók creates a complex rhythmical counterpoint using rhythmical asymmetry, achieved by beaming across bar lines, syncopated accents, and unequal metrical division within bars (Ex. 5.12).

Ex. 5. 12: Fourth Quartet, movement 1,

bars 17-22.

A similar effect is used in the fifth movement, where Bartók uses sforzandi accents to define rhythmical irregularity within a regular 2/4 meter (Ex. 5.13).

Ex. 5.13: Fourth Quartet, movement 5, bars 19-23.

Janos Kárpáti points out that this movement has a form of a “loud robust dance with drumlike accompaniment,” which Bartók probably derived from his experiences of North African music in 1913.[31]

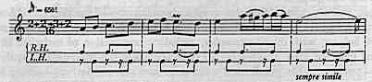

The most direct connection between Bartók’s music and Bulgarian rhythm can be found in his collection of didactic piano pieces, Mikrokosmos (1926-1939). This collection, which is a series of progressive piano pieces designed for piano teaching, explores many of the basic folk music influences that permeate Bartók’s work. The pieces numbered 113, 115 and 148-52 are all composed using Bulgarian rhythm. The following example is notated in one of the most popular forms of Bulgarian rhythm (2+2+3) (Ex. 5.14).

Ex. 5.14: Mikrokosmos No. 117, bars 1-6.

In addition to writing music in a rhythmically asymmetrical model of composition, Bartók also derived symmetrical patterns from folk music sources. Judit Frigyesi shows that the first and second subjects of the first movement of the Piano Concerto No.1 (1926) are derived from the repetitive kolomeika rhythm.[32] These songs have a symmetrical structure with the characteristic rhythmical schema (4 x quavers / 2 x quavers + crotchet). In this movement Bartók created a composition derived from one basic rhythmical idea, which Janos Kárpáti describes as a “proto-rhythm” that “serves as a basis from which a number of themes of the composition are set forth”.[33] Frigyesi points out that a transformation of the main themes into an asymmetrical form of presentation occurs between the exposition and the recapitulation. Frigyesi describes how Bartók distorted his folk music model by twisting the structural parts out of their natural relation, displaying more concern for the energy of the folk model than its surface form.[34] Rather than religiously following any one model, Bartók tends to adapt and transform a model according to his own expressive needs.

Modality

After a period of experimentation with abstract, atonal chromaticism in works such as: Miraculous Mandarin, Three Studies and the Violin Sonatas, Bartók concentrated on modality as a primary means of organising pitch structures. In his mature works he assimilated his knowledge of non-diatonic folk modes into his music. One of the most significant works to make this transition was the Cantata Profana (1930), which adopted non-diatonic modal material as the main source of modal material. Antokoletz points out that while interactions of diatonic, whole-tone and octatonic scale are common to many of Bartók’s works; it was the Cantata that was most successful in integrating non-diatonic scales into western art music.[35] The Cantata was an ambitious project that achieved a synthesis of various folk music elements borrowed from the Transylvanian region of Romania. Bartók derived both the text and modal material for the Cantata from the Romanian colinda (Christmas songs).

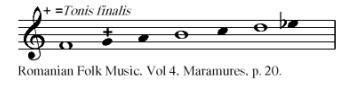

The most prominent scale used in the Cantata Profana

is the Romanian folk mode (better known as the acoustic scale) (Ex.

5.15). Griffiths points out that this scale,

characterised by its augmented fourth and flattened seventh, had

its debut as early as Bartók’s second Romanian Dance

for piano (1909-10). In his study Romanian Folk Music

Bartók lists a total of seven songs that use this scale (Ex.

5.16).

Ex. 5.15: Category no. 15 from Bartók’s table: Scale and range in the Colinda melodies.

Ex. 5.16: Melody with Romanian folk mode, collected by Bartók in 1914.[36]

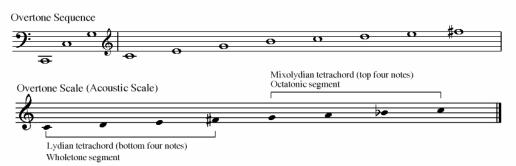

The Hungarian musicologist Erno Lendvai demonstrated how this scale is based on the first sixteen harmonics of the harmonic series.[37] It can also be shown that is comprised of a bottom half Lydian scale and a top half Mixolydian scale. These two tetrachords are closely related to segments of the diatonic, whole-tone and octatonic pitch collections (Ex. 5.17).

Ex. 5.17: Acoustic Scale based on the notes of the overtone sequence.

The closing tenor solo of the third movement of the Cantata Profana uses a complete Romanian scale (D-E-F#-G#-A-B-C-D) (Ex. 5.18), and the opening bars use a derived form (D-E-F-G-Ab-Bb-C-D) (Ex. 5.19).

EX. 5.18: Cantata Profana, Movement 3, bars 72-77.

Ex. 5.19: Cantata Profana, Movement 1, bars 1-3.

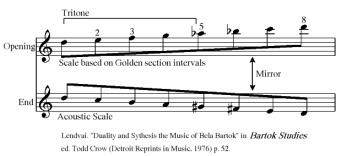

Lendvai shows how these scales mirror each other in an inversional relationship (Ex. 5.20). He proposes a theory of a duality in Bartók works, involving two harmonic worlds, which compete with each other. The first scale of the Cantata belongs to the world of the golden section system, which revolves around the intervals expressed by the Fibonacci numbers 3:5:8. The final scale is derived from the acoustic system based on the overtone series. Lendvai further polarises these harmonic identities by characterising the golden section system as dissonant, and the acoustic system consonant.

An Equally deep secret of Bartók’s music (perhaps the most profound) is that the “closed” world of the golden section system is counterbalanced by an open sphere of the acoustic system.[38]

Ex. 5.20: Scales from the Cantata Profana

Antokoletz, on the other hand shows the derivation of pitch materials from one modal family. Demonstrating the link between each of these two scale forms contradicts Lenvai’s theory, which tends to focus on the differentiated aspects of scale formations. Antokoletz show that the first scale is derived from the second by a process of rotation and transposition, which is not unlike the manner in which church modes are created by a rotation of diatonic scales.[39]

Rotation 1 D E F# G# A B C (D)

Rotation 3 F# G# A B C D E (F#)

Transposed

Rotation 1 D E F# G# A B C (D) [closing scale]

Rotation 3 D E F G A Bb Cb(D) [opening scale]

Antokoletz goes on to point out that Bartók achieves the transformation from one form of the scale to next by extending the basic modes to octatonic and whole-tone collections:

The approach is based on highly complex interactions between members of the larger family of non-diatonic folk modes from Easter Europe and symmetrical (whole-tone and octatonic) constructions of contemporary art music.[40]

It can be shown that the forms of non-diatonic scales, which already contain octatonic and whole tone segments are can be extended to complete statements of these collections.

Octatonic.

Whole-tone.

D-E-F-G-Ab-Bb

- B-C# - (D) D-E-F#-G#

/Ab-BbC- (D)

Opening

scale. Extension.

Closing scale. Extension.

The above whole tone scale implies the transposition of the whole-tone tetrachord of the closing scale (Ab-Bb-C-D) to a tetrachord of the closing scale (D-E-F#-G#), illustrating the symmetrical transformation of one scale type to another. Antokoletz says that these extensions belong to the intermediary stage of overall modal transformation, which is linked to the musico-dramatic conception of the work.[41]

It can be shown that non-diatonic modes permeate much of Bartók’s mature music. Lendvai provides examples of the acoustic scale in works such as: Duke Bluebeard’s castle op. 11 (1911), The Wooden Prince (1914-16), String Quartet No. 4 (1928), Music for Strings Percussion and Celeste (1936), Sonata for two Pianos and Percussion (1937), Contrasts (1938), and Divertimento (1939).[42] An examination of these works is beyond the remit of this paper, but on the whole it can be found that they all exhibit the tendencies of Bartók’s lifelong commitment to the synthesis of divergent modal material with the techniques of western art music.

Notes

[1] Malcolm Gillies. “Béla Bartók” in New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, 2nd ed. Vol. 2, p. 796.

[2] Bartók, “The problem of the Modern Music” (1920) in BBE. p. 456.

[3] Wilson, “Approaching Atonality: Studies and Improvisations” in BC (1993), p. 162.

[4] Bartók, “Harvard Lectures” (1943) in BBE. p. 375.

[5] Griffiths, 1984, p. 26.

[6] Ibid., p. 341-342.

[7] Schoenberg, “Folkloristic Symphonies” (1947) in Style and Idea, ed. Leonard Stein, (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), p. 183

[8]Wilson,1993, p. 166-71.

[9] Ibid., p.168.

[10] Lampert, “Works for Solo Voice and Piano” in BC, p. 398.

[11] Ibid. pp 388-99.

[12] Ibid. p. 401.

[13] Willson, “Vocal Music: Inspiration and Ideology” in CCB, p. 84.

[14] Griffiths, 1984, p. 30.

[15] Szabolcsi. “Bartok’s Principals of Composition” in BS, p. 19.

[16] Ibid. pp. 19-20.

[17] Griffiths, 1984, p. 30.

[18] Ibid. p. 30.

[19] Benjamin Suchoff, 1993, pp. 125-126.

[20] Bartók. “The Relation Between Contemporary Hungarian Art Music and Folk Music” (1941) in BBE, p. 349.

[21] Paul Wilson. “Violin Sonatas” in BC, p.246.

[22] Ibid. p.247.

[23] Ibid. p.252.

[24] Peter Laki. “Violin Works and the Viola Concerto” in CCB, p. 137. The folk source of this motto was identified in a lecture given by Lázló Somfai in 1977.

[25] Bartok. “Hungarian Folk Music” (1921) in BBE, p. 62.

[26] Bartók. “Romanian Folk Music” (1938) in BBE, p. 155.

[27] Example 8 in “Some Problems of Folk Music Research in East Europe” (1940) in BBE, p. 182.

[28] Timothy Rice. “Béla Bartók and Bulgarian Rhythm” in BP, p. 196.

[29] Bartók. “The So-Called Bulgarian Rhythm” (1938) in BBE, p. 44.

[30] Ibid.

[31]Kárpáti. “Bartók in North Africa” in BP, pp. 181-82.

[32] Judit Frigyesi. Béla Bartók and Turn-of-the-Century Budapest (Berkeley: Uni. Of California Press, 1998) p. 123.

[33] Janos Kárpáti. “The first two piano Concertos” in BC, p. 502.

[34] Ibid. p. 128.

[35] Antokoletz, 1984, p. 205-206.

[36] Bartók. RFM, p. 121.

[37] Erno Lendvai. Béla Bartok: An Analysis of his Music (London: Kahn & Averill, 1971) p. 67.

[38] Erno Lendvai. “Duality and Synthesis in the Music of Béla Bartók” in Bartók Studies. Ed. Todd Crow (Detroit Reprints in Music, 1976) p. 52.

[39] Antokoletz. “Modal Transformation and Musical Symbolism in Bartók’s Cantata Profana” in BP, p. 62.

[40] Ibid. p. 74.

[41] Ibid. p.66-67.

[42] Erno Lendvai. “Duality

and Synthesis in the Music of Béla Bartók” BS.

in pp 67-70.