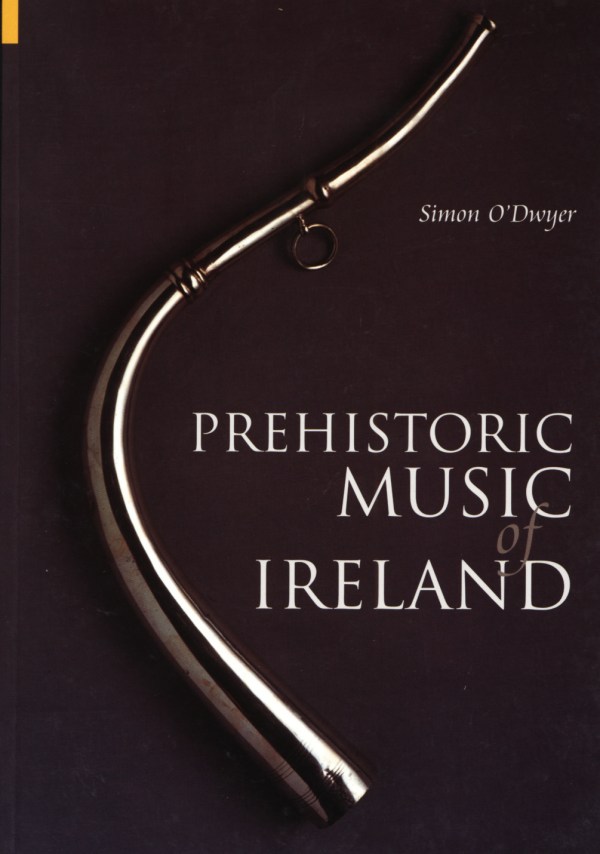

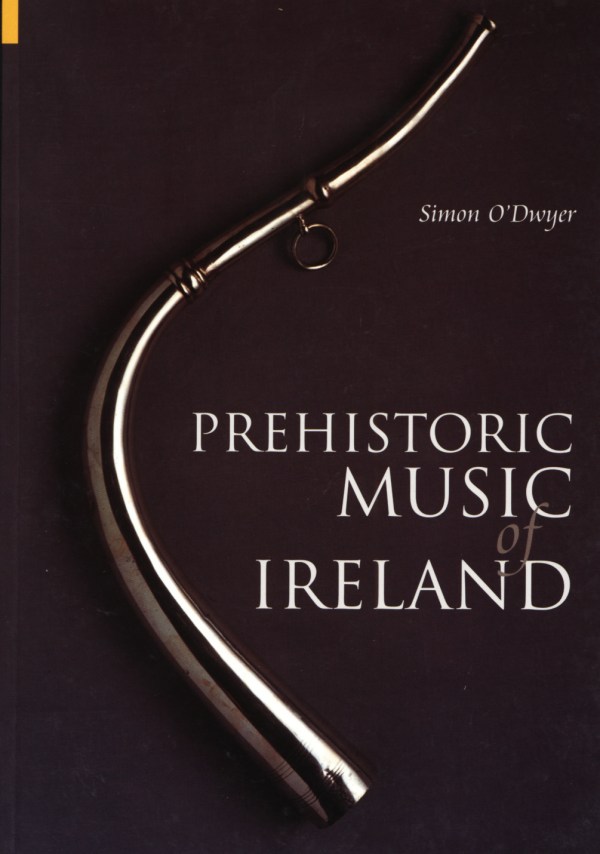

‘Prehistoric Music of Ireland’ by Simon O’Dwyer,

published by Tempus Publishing,

The Mill, Brimscombe Port,

Stroud, Gloustershire, GL5 2QG

UK

ISBN 0-7524-3129-3 www.tempus-publishing.com

|

|

To order:

| www.tempus-publishing.com | www.amazon.co.uk | www.amazon.com | www.prehistoricmusic.com |

The book is an exploration of the ancient musical instruments of Ireland based on the latest findings of archaeology, supplemented by information contained in some of the Early Medieval manuscripts and numerous legendary references.

Recent research into Bronze Age wooden pipes, bronze horns, Iron Age Celtic trumpas and Early Medieval  instruments has revealed a musical world of great richness and diversity. These investigations have uncovered fascinating evidence of ancient music and the possibility that it may be the origin of the musical tradition which is so much a part of Irish life today.

instruments has revealed a musical world of great richness and diversity. These investigations have uncovered fascinating evidence of ancient music and the possibility that it may be the origin of the musical tradition which is so much a part of Irish life today.

Simon O’Dwyer has dedicated his life’s work to the study and (with others) the reconstruction of prehistoric instruments. He is in the vanguard of the pioneering research which is taking place into the music of prehistory around the world. This work sheds new light on the practices of ancient civilizations and the important role that music had to play within them.

The history of music that investigates its diversity, traditions, instruments, styles and contexts presents a complex narrative that we can be slow to understand. This contrasts with the speed at which modern musical trends and fashions can spread through society, urged on by new technology and commercial hype. Terms such as ‘house’, ‘rock’, ‘metal’ and even ‘the stones’-words that are often used by archaeologists-mean something entirely different in the context of modern popular music, representing some of the main categories of the myriad of musical classifications that occupy our contemporary airwaves.

The history of music that investigates its diversity, traditions, instruments, styles and contexts presents a complex narrative that we can be slow to understand. This contrasts with the speed at which modern musical trends and fashions can spread through society, urged on by new technology and commercial hype. Terms such as ‘house’, ‘rock’, ‘metal’ and even ‘the stones’-words that are often used by archaeologists-mean something entirely different in the context of modern popular music, representing some of the main categories of the myriad of musical classifications that occupy our contemporary airwaves.

The prehistory of music is a different matter altogether. Up until now a book bearing such a title would have been virtually unimaginable. It is sometimes interesting to wonder about the sounds that someone in prehistory would have been familiar with-the twang of a bow as it shoots its arrow, or the roar of a bull traversing some distant meadow. Imagine the rhythm of human grumbles and groans that form the bass line to the grumpy concerto of instructions barked out by some prehistoric foreman as the capstone of a portal tomb is laid to rest on top of megalithic orthostats.

In ‘Prehistoric Music of Ireland’, Simon O’Dwyer adds significant new dimensions to our appreciation of prehistoric societies through his obvious hunger for knowledge of their musical repertoire. He traces the fragmentary nature of our knowledge of music throughout the ages, concentrating on the prehistoric period but also including instruments and illustrations from the medieval period. This book is chronological in its approach to ancient instruments, supplemented by chapters on music in legend, images and reconstructions. The colour images in the book remind us that even in prehistory highly polished musical instruments convey a sense of sophistication and opulence.

Little evidence for musical instruments survives from the Neolithic. However, O’Dwyer speculates that the frame drum is likely to have existed in prehistoric Ireland. Such an instrument would be the antecedent of the bodhrán widely played (so widely played!)in traditional music sessions throughout the country and beyond. Even the intricate rhythms of rattling bones are a distinct possibility. In amongst the archaeological late Bronze Age hoards (early first millennium BC) that have been recovered in Ireland over the past couple of centuries are a collection of horns, which were recovered in not insignificant numbers throughout Ireland. These instruments, which are the principal focus of the book, had lain mute in museum cabinets and displays until Simon O’Dwyer arrived and unlocked their sounds, harmonics and resonances.

Basically, nobody had much of an idea of how to make these prehistoric bugles sing until O’Dwyer reassessed the possibilities. The tradition of how to get a note out of them was well and truly broken. Previous attempts to play such instruments led to serious injury. In 1857 the unfortunate Robert Ball had gathered all his energy to blow a note on a prehistoric side-blow horn-he burst a blood vessel and died not long after. A more ancient accident was recorded in the twelfth century by Geraldus Cambrensis, who states that a certain monk who blew on a sacred bronze horn that had allegedly belong to St. Brendan appears to have suffered some kind of stroke.

O’Dwyer presumably aware of previous casualties followed up an idea by Peter Holmes that the horns would have been played in the same fashion as a didgeridoo and not in the fashion of a modern brass player (mouthpieces to facilitate the modern style of playing were always missing). In many examples the aperture for blowing is located on the side of the instrument. Using circular breathing techniques and playing in alternation with other musicians, prehistoric man could have played an impressive range of sounds and music. O’Dwyer notes that the fact that some horns are found as collections indicates that the originals would have been played in an ensemble and most likely in ceremonial.

Further chapters deal with the Loughnashade trumpet and its S-shaped assembly, and the Ard Brinn example found in County Down in 1801. The Bekan horn from County Mayo, dating from the seventh century AD, is also featured. O’Dwyer further highlights the sophistication of the techniques involved in the manufacture of the horns, along with their intricate design and decoration. Even the enigmatic crotals, found in large numbers in the famous late Bronze Age hoard from Dowris, Co. Offaly, are more likely to be hand-bells for accompaniment of the horns.

Through reproduction of various instruments O’Dwyer relates to us his detailed insights into the manufacturing techniques; he also explores the musical ranges, dynamics and possibilities which otherwise would have been impossible on the original instruments owing to their delicate nature and archaeological value. The reproduction of the instruments has allowed him and his colleagues in Prehistoric Music Ireland to portray the sounds on three CD recordings. One discovery in recent times necessitated an additional chapter on what O’Dwyer is calling ‘the Wicklow Pipes’, discovered by Bernice Molloy at the bottom of the trough of a fulacht fiadh during excavations in County Wicklow (Archaeology Ireland 68, 5) The radiocarbon date for the trough is c.2150 BC and Ms. Molloy is suggesting that the pipes are of a similar date, making them not only ancient but also having a degree of sophistication that requires explanation. O’Dwyer considers that the large tubes may be part of an organ or that they were tied together with the appearance of pan-pipes.

O’Dwyer’s research is impressive and his enthusiasm evident. I have no doubt that he will find it necessary to produce an updated version of the book as knowledge of this most ‘untraditional Irish music’ increases. Complemented by his audio recordings and the speculative musical recreations, this book certainly urges a reappraisal of the musical capabilities of prehistoric man in Ireland. Tom Condit, Editor, Archaeology Ireland, Winter 2004.

Prehistoric Music Ireland,

Crimlin, Corrnamona,

Co. Galway, Ireland

Phone: +353(0) 949 548 396

bronzeagehorns@eircom.net

©2005,PREHISTORIC MUSIC IRELAND