|

Asylum Seekers and Immigrants in Ireland Global Labour market |

The

Global Labour Market -

A Case for Open Borders?

The global labour market continues, in many ways, to operate to the disadvantage of the countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America (the 'South'). The Philippines, for example, has seen over 12 per cent of all its qualified professional workers emigrate to the United States, while 60 per cent of all doctors trained in Ghana in the early 1980s ended up emigrating. This represents a double-loss to the countries concerned: they lose the people themselves and the contribution they would have made, and they also lose the money they invested in training them.

The current immigration policies of Western countries (the 'North') encourage this loss by giving preference to immigrants with special skills or with capital to invest, thus promoting the drain of skills and money out of poor countries. The Irish 'passports for cash' scheme was just one example of this.

If the North was seriously interested in 'developing' the South, it would make more sense to encourage the immigration of less skilled, poorer people who might otherwise be unemployed at home. These people could then work in the North and send money home to their own countries (emigrants' "remittances", which were a vital source of earnings to Irish families over the years). A 1992 study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimated that if the North relaxed restrictions on immigration from the South, then poorer countries could earn at least an additional $250 billion every year - five times the amount of development aid that Northern governments give to the South.

Of course, it would be better if nobody had to emigrate from the South - if everyone could find a job at home - but the reality is that they cannot. And present policies mean that they are denied the option of finding a job elsewhere, or else they are criminalised for trying to do so. Allowing more open borders, rather than selectively sucking out skills and capital, would be one means for the North to begin to redress the damage its control of the global labour market has wreaked on the South over the years.

Global Labour Market

Government ministers, journalists and others regularly label people coming to Ireland as 'economic migrants' rather then 'genuine' refugees. The implication of this distinction is that those 'merely' fleeing poverty or unemployment are not deserving of our support. It is sometimes argued in response that this is hypocritical, because Irish people have themselves a long history of being economic migrants - moving to Australia, the US, England and elsewhere in search of work. There are now one million Irish-born people living overseas, and none of them is a refugee. Since the seventeenth century, seven million Irish people have gone into one or another form of exile, and few of them would have qualified for refugee status - they were usually fleeing poverty and hunger, not political persecution. This

is all true, and, in the light of that, the hypocrisy of current Irish

attitudes is obvious. But an emphasis on Irish migration can sometimes

cloud the fact that economic migration has a long history and that it

has affected hundreds of millions of people all over the world.

This

is all true, and, in the light of that, the hypocrisy of current Irish

attitudes is obvious. But an emphasis on Irish migration can sometimes

cloud the fact that economic migration has a long history and that it

has affected hundreds of millions of people all over the world.

The history of economic migration on a global scale can be dated to 1492 and Columbus' conquest of the Americas. What followed was annihilation of the native American population: in 1518, Mexico had a population of more than 11 million, but by 1568 that population, reeling from European massacres and the effect of European diseases, had fallen to a mere 2.5 million. But the European conquerors needed labourers to work the mines and plantations, and the solution they adopted - the 'importation' of African slaves - marked the emergence onto the world stage of the first large-scale group of economic migrants.

In 1570, there were 40,000 African slaves in Spanish-controlled America - by 1650, that number had risen to 857,000, with many more working on the sugar plantations of Brazil and the Caribbean, and countless others dragged off to the cotton plantations of the southern United States. Exactly how many Africans were affected by the European-run slave trade is unknown, but a minimum number of 12 million had landed alive in the Americas by the middle of the nineteenth century, and at least 2 million had died on the journey.

Conditions on board the ships were unimaginably awful, with bodies packed together so close that, according to one eyewitness, a person's body 'becomes contracted into the deformity of the position, and some that die during the night, stiffen in a sitting posture; others, who outlive the voyage, are crippled for life'. Slaves were, quite literally, allocated less room than they would have had in a coffin. Slave traders would pack in as many bodies as possible, calculating that the profits from maximum numbers made the risk of death and injury to some worthwhile. Chained to rough timber, a rough crossing meant that the skin on slaves' elbows would commonly be worn away to the bone.

The most skilled and productive African workers - for example, healthy young metal workers and miners, both men and women - were most in demand. Between 1650 and 1850, the total population of Africa remained static but the populations of Europe and Asia doubled. This was a blow from which the social and economic fabric of Africa has never recovered. Not only were individuals lost, but whole societies were traumatised and whole political systems undermined. The present underdevelopment of Africa cannot be understood without reference to this legacy.

The transport of slaves from Africa was organised on a so-called 'triangular' basis: European ships sailed to Africa with goods (including weapons) which they exchanged for slaves. The slaves were brought to the Americas, and the ships loaded with sugar, rum, cotton and other goods (goods the slaves themselves produced) for ultimate sale - at enormous profit - back in Europe. Great fortunes accrued to Europeans, and part of these fortunes was invested in industrial development; the present wealth of Europe is, in part, based on the deliberate impoverishment of Africa. The present development of Europe cannot be understood without reference to this legacy.

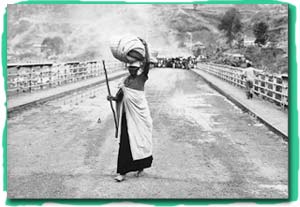

After the abolition of slavery, alternative forms of economic migration rose to prominence, including 'coolie' labour from Asia in the nineteenth and early twentieth century: workers from India, China, Japan and Java went to work on plantations, in the mines and on the railroads of North America, and as domestic servants everywhere. More than 30 million people left India alone as 'coolies' between 1834 and 1937. The 'coolies' were usually recruited on fixed-term contracts and might go into debt to finance their travel - paying off that debt and honouring the contract meant that they were slaves in all but name. Like the slaves before them, transport was arduous, with up to one in five dying in transit between India and the Caribbean in the mid-nineteenth century. Like the Irish at this time, the reason for migration was often famine or the threat of famine. No more than the end of slavery, the formal end of 'coolieism' did not mean the end of a global market for labour. To take just one recent example, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Western European countries actively recruited millions of mostly manual labourers under the so-called 'guest worker' system: Britain recruited West Indians and Asians, France North Africans, the Netherlands Indonesians and Surinamese, Germany Turks and other southern Europeans. By the mid-1970s, 10 per cent of the German and French workforces consisted of people born outside those countries. The post-war prosperity of those countries, prosperity from which Ireland benefited through expanding export markets and EEC/EU transfers, was partially built on the backs of such 'guest workers'. The 'guest worker' agreements were mostly suspended by Western European governments in 1974 with the onset of recession - having benefited from foreign-born labour for decades (indeed, one could argue, centuries), European governments decided to try and pull up the drawbridges and create a 'Fortress Europe'.

Reviewing the history of economic migrants is not a purely academic exercise. For one thing, it shows us that the line between 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' migration can be a very fine one indeed. It also shows us that the mass movement of people has been a critical component of the global economy for centuries, involving enormous human pain and suffering, and enormous wealth for some. Many Irish people have experienced the pain, and some, especially in more recent years, have also experienced some of the benefits. Irish people have played a role, a winning and a losing one, in the global labour market; we cannot stand apart from it now.

| Calypso

Productions South Great George's St. Dublin 2, Ireland T (353 1) 6704539 F (353 1) 6704275 calypso@tinet.ie |

![]()

— Welcome

- About - Productions

- Theatre and Social Change -

— Racism - Refugees

and Asylum Seekers - Prisons -