|

Asylum Seekers and Immigrants in Ireland -

Asylum |

|

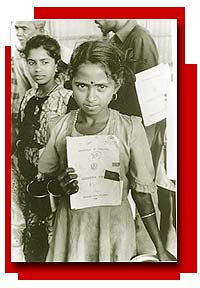

'The status of refugees is an issue which should strike a chord with every man, woman and child here who has any grasp of Irish history, our history being littered with the names and deeds of those driven from our country out of fear of persecution' (John O'Donoghue TD, 1996). Yet, in 1998, John O'Donoghue was labelling over 90 per cent of asylum-seekers in Ireland as frauds, despite the fact that the vast majority had not even had their cases heard. Potential refugees had gone from being reminders of a glorious, albeit persecuted, Irish past, to being criminals. But the effective criminalisation of an entire community is not confined to the Department of Justice. The Irish Government's 1996 White Paper on Foreign Policy was produced by the Department of Foreign Affairs. It was widely hailed as a progressive statement of Irish policy towards development issues. On the issue of refugees, the Paper claimed that there would be 'renewed emphasis' on 'responding to the growing number of refugees and displaced people'. But the White Paper had almost nothing to say about the situation of refugees coming to Ireland. It did have something to say about EU-level asylum policy, but the discussion of this matter was considerably overshadowed by discussion of 'issues such as drugs, extradition and organised crime'. By including the issue of asylum within this context, the clear implication is that it is somehow associated with criminality rather than constituting a human rights issue. In the paragraphs dealing with EU justice issues, there are 6 references to drugs, 3 to crime, and 1 each to fraud, police cooperation, extradition and terrorism; immigration is mentioned once, and asylum not at all. When politicians and civil servants routinely and consistently associate refugees and asylum-seekers with criminality, this must reinforce public hostility and thus contrinute to the climate in which racist attacks can (and increasingly do) occur. |

![]()

- everyone has the right to seek and enjpy in other countries asylum from persecution art.16, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

A S Y L U M

A refugee is a person who, according to the relevant 1951 UN Convention (to which Ireland is a signatory), is fleeing persecution because of their race, their religion, their nationality, or because they hold a particular political opinion. Ireland, like every other country, is legally obliged to offer such a person protection from persecution. In 1997, 3,883 asylum-seekers (people requesting refugee status) arrived in Ireland. That may seem like a lot, but it is still a relatively small number compared to other European countries: for example, Hungary, a poorer country than Ireland, dealt with 6,000 asylum applications in 1996.

In

fact, the whole of Europe receives only 5 per cent of the world's asylum-seekers,

because the vast majority of those forced to flee go to neighbouring countries,

countries often as poor, if not poorer, than their own. The hospitality

of such countries puts 'Ireland of the Welcomes' to shame. For example,

Tanzania, which is a so-called 'priority country' for the receipt of Irish

development aid, has struggled in recent years to cope with over half

a million refugees, yet Tanzania is twenty-five times poorer than Ireland.

Despite Ireland's relatively small number of asylum-seekers, it seems

to be beyond the capacity of this state to deal with them in a decent

manner. Their legal position is uncertain because the Refugee Act, which

should establish the basic ground rules and which passed with all-party

support in the Dail in 1996, is still not in operation. As Trocaire has

recently observed, 'Why Ireland, uniquely among EU member states, should

feel that it can get by with ad hoc procedures rather than the legislation

passed by our democratically elected representatives is a mystery'. In

the meantime, most applicants wait 2-3 years for decisions on their cases

and thousands are caught in an applications backlog, during which time

they are not allowed work to support themselves (although in the UK an

asylum-seeker can work if their claim has not been processed within six

months).

In

fact, the whole of Europe receives only 5 per cent of the world's asylum-seekers,

because the vast majority of those forced to flee go to neighbouring countries,

countries often as poor, if not poorer, than their own. The hospitality

of such countries puts 'Ireland of the Welcomes' to shame. For example,

Tanzania, which is a so-called 'priority country' for the receipt of Irish

development aid, has struggled in recent years to cope with over half

a million refugees, yet Tanzania is twenty-five times poorer than Ireland.

Despite Ireland's relatively small number of asylum-seekers, it seems

to be beyond the capacity of this state to deal with them in a decent

manner. Their legal position is uncertain because the Refugee Act, which

should establish the basic ground rules and which passed with all-party

support in the Dail in 1996, is still not in operation. As Trocaire has

recently observed, 'Why Ireland, uniquely among EU member states, should

feel that it can get by with ad hoc procedures rather than the legislation

passed by our democratically elected representatives is a mystery'. In

the meantime, most applicants wait 2-3 years for decisions on their cases

and thousands are caught in an applications backlog, during which time

they are not allowed work to support themselves (although in the UK an

asylum-seeker can work if their claim has not been processed within six

months).

- everyone has the right to work art.23 (1), Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Not allowed to work to support themselves, applicants find that the support provided by the state is completely inadequate. For example, the underfunded Irish Refugee Council can no longer provide everyone with an acceptable standard of legal advice; and even the Refugee Act, if it ever does come into force, contains no provision for free legal aid for asylum-seekers.

The Refugee Act was supposed to establish an independent appeals mechanism, but the Irish government has already backed away from this: the role envisaged in the Act for an independent refugee commissioner is now to be carried out by a 'person appointed by the Minister'. Deportations of people under these flawed procedures have already begun.

- everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal art.10, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

What is required is for the Refugee Act to be immediately implemented to ensure that cases are processed within a reasonable timeframe, with guarantees built in to guard against unfair deportations. And the Act also needs to be extended to ensure that asylum-seekers are entitled to legal aid, and are thus able to present their cases fairly and fully. Asylum-seekers should also be allowed work while awaiting decisions on their cases. The absolute minimum is that the Irish government should stop its degrading treatment of asylum-seekers, as exemplified by the spectacle seen last year of asylum applicants being reduced to standing for hours in the rain on a Sunday afternoon to fulfil registration demands made on them by the Department of Justice.

- no one shall be subject to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment art.14, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

![]()

The above represents the minimum necessary to protect the rights of asylum-seekers. What then of 'economic migrants', 'merely' fleeing in search of a better life rather than from persecution? In practice the distinction can be a very fine line - hunger can kill as surely as a soldier's bullet. And do people not have a right to try and escape poverty and unemployment? Is that not what countless thousands of Irish people have done over the years? And did we not lobby for green cards and other rights for our very own 'economic migrants'?

Yes, it may be responded, but the USA and other countries only took those people in because they could make use of them - as construction workers, as au pairs, etc. This is true, and it is precisely the point - immigrants are economically useful. They work long hours, doing jobs that local people are usually not available to undertake. They spend money in the host society, and when they are legally recognised they pay taxes, helping support the jobs, welfare payments and pensions of other people in that society. Very often, immigrants start up their own businesses, directly creating (not displacing) jobs.

Immigration, in other words, is often an economic blessing, not a curse. And Irish people should know this already: between 1991 and 1996, there were 177,000 immigrants to Ireland, people without whom the Irish economy and society could barely have functioned. It is obvious that industries like computer software and translation could not survive without foreigners. Most of the people working here now are from Western Europe and North America, but there is no reason other than racism not to be equally welcoming to people from elsewhere.

Of course, the needs of asylum-seekers are the most urgent. But there is no excuse for the demonisation and criminalisation of 'economic migrants'. Their impact on Irish society could well be positive, and it is perverse to scapegoat them for problems of crime, unemployment and housing shortages - problems which were far more severe long before any recent increase in immigration.

| Calypso

Productions South Great George's St. Dublin 2, Ireland T (353 1) 6704539 F (353 1) 6704275 calypso@tinet.ie |

![]()

— Welcome

- About - Productions

- Theatre and Social Change -

— Racism - Refugees

and Asylum Seekers - Prisons -