JOHN S. BECKETT

(5th February, 1927 – 5th February,

2007)

Irish musician,

composer and conductor,

and cousin of the writer and playwright Samuel Beckett.

John Beckett with

the German conductor Otto Matzerath, at the Weber

harpsichord in the National Museum, Dublin , 1950.

(Courtesy of Gillian Smith.)

John

Stewart Beckett and his twin sister Ann were born in Sandymount, Dublin to

Gerald and Peggy Beckett. Gerald, brother of Bill Beckett (Samuel Beckett’s

father), studied medicine at Trinity College Dublin and became County Medical

Officer for Wicklow. Gerald played rugby for Ireland, and captained a golf

club. A quiet man with wide interests, he was quite irreligious, with a dry

sense of humour, describing life as “a disease of matter”. He was very musical

and enjoyed playing piano duets with a neighbour (David Owen Williams, who

later became a director in the Guinness Brewery) and also with his nephew

Samuel Beckett and with his son John. John inherited his father’s mordant wit,

but not his love of sport.

John

attended St Columba’s College, Dublin, where he was taught music by Joe Groocock, whom he admired little short of

idolatry, and who furthered his lifelong devotion to the music of Johann

Sebastian Bach. (John shared the same initials, J. S. B., with the famous

composer.) John wrote his first fugue at around the age of fourteen in the

Groocock family home while visiting one weekend.

John’s

father’s friend Mr Williams, who had served in Germany during World War II,

brought home a complete set of vocal scores of Bach’s Cantatas, which made a

huge impression on John.

The

Becketts lived for a time in Dundrum and then, in 1933, moved to Greystones,

County Wicklow. John’s father worked in Rathdrum, also in Wicklow.

John furthered his study of music by attending the Royal College of Music in London. He was there in 1948 but spent the year of 1949 in Paris, where he studied composition under Nadia Boulanger and taught English in a school at Saint Germain-en-Laye. He returned to Dublin in 1950 and his father died in September of that year. Between 1950 and 1952, he befriended the pianist, organist and harpsichordist John O’Sullivan, Michael Morrow (whom he met in the National Library) and the singer Werner Schürmann. Michael Morrow (1929-1995), who was born in England but lived in Ireland at that time, studied in the National College of Art and was a self-taught musician – his father had given him a present of a recorder when he was fourteen years of age. He brought John to his home at Strand Road, Merrion and, playing his lute, accompanied his teenage sister Brigid who sang songs by John Dowland. Michael, Brigid, Werner and John Beckett played recorders and Werner’s small octavino (a portable spinet tuned an octave higher than normal pitch) came in handy as a continuo instrument. John persuaded Werner to sing some German songs for a Radio Éireann broadcast. At around this time, John also met the harpsichord maker Cathal Gannon. John obviously formed a favourable impression of Cathal, for he later said, ‘I took to him like a duck to water. I liked him, I respected him and I respected his knowledge, his interests, his enthusiasm, his simplicity, his directness, and became very, very, very affectionately fond of him.’

To celebrate the bicentenary of Bach’s death in 1950, John played the harpsichord continuo part in a performance, in the Metropolitan Hall, Dublin, of Bach’s B minor Mass, sung by the Culwick Choral Society and the Radio Éireann Choir, conducted by Otto Matzerath. The historic Weber harpsichord of circa 1768 was borrowed from the National Museum for the occasion, but as it could not be tuned up to the correct pitch, John was obliged to transpose and play the continuo part (the ‘thorough’ or ‘figured’ bass) in C minor – a semitone higher – while the rest of the orchestra played in the original key. John remembered that the harpsichord was not in good condition.

John met Vera Slocombe, who had been married to the cinematographer

Douglas Slocombe, in Dublin sometime around 1950 and lived with her in a flat

in Hatch Street, moving later to a flat in Baggot Street. John and Vera went to

London in 1953 with Michael Morrow, who shared a flat with them first in

Islington and then in Hampstead until Michael got married. John and Michael

often played in a restaurant in Picadilly named Forte’s Musical Fountain,

earning a few pounds a week. Following the move to London, Michael gave up

painting and concentrated on music.

John was back in Dublin again by 1958, when the first complete

performance of Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion took place, with Victor Leeson

conducting the St James’s Gate Musical Society. As it was believed that a

harpsichord was not available, John played on a piano that had drawing pins

attached to the hammers in order to give it a harpsichord-like sound. When the

work was performed again the following year in the St Francis Xavier

Hall, Upper Sherrard Street,

using the same forces, Cathal Gannon’s new harpsichord was used. The continuo

part was played by David Lee on the organ, John on the harpsichord and by Betty

Sullivan on the cello – a collaboration that would last for many years. Although

poorly attended because of a gala concert at the Gaiety Theatre on the same

evening, the performance was a tremendous success and critiques in praise of it

appeared in four national newspapers on the following day. One reviewer wrote:

Betty Sullivan and John Beckett were a lovely continuo. Mr. Beckett was a little insistent at times in the orchestral passages, but his realisation of the harpsichord part was at all times beautifully apt and exciting.

In 1960, Musica Reservata, a group specialising

in Renaissance music was founded in London and was directed by Michael Morrow

and conducted by John Beckett. The group performed in England and on the

continent during the sixties and seventies and made many recordings. In addition

to being a keyboard player, John played the recorder and viol. John also

composed avant-garde incidental music for various experimental dramas broadcast

on the BBC Third Programme; he collaborated with his cousin Samuel, writing

music for his stage work, Act Without Words and his radio play Words

and Music.

By 1961

John was back in Ireland and was involved in a serious car accident in which he

broke his two arms, a hip and an ankle. Whilst recovering in hospital over a

period of five months, he practised his music on a clavichord that his friend,

Cathal Gannon, had made some years previously. Later in the year he married his

partner, Vera. At around this period a record was made of music played by John

on Cathal’s first harpsichord. In 1963, John appealed to his father’s friend,

David Owen Williams, now a director in the Guinness Brewery, to provide Cathal

with a special workshop in which he could make harpsichords and restore antique

pianos. John was present (and photographed) at the handing-over ceremonies in

the Brewery when a harpsichord was donated to the Royal Irish Academy of Music

in 1965 and another sold to RTÉ in 1966.

Bach’s

Saint Matthew Passion was performed again in the Concert Hall of the Royal

Dublin Society in March 1966, in which the continuo was played by John

O’Sullivan on the organ, John Beckett on the harpsichord and Betty Sullivan on

the cello. The performance featured two orchestras conducted by Victor

Leeson, The Guinness Choir, The O’Connell School Boys’ Choir and various soloists,

including Bernadette Greevy.

John

returned to England, where he taught the recorder and had a viol consort class

at Belmont School, which was attached to Chiswick Polytechnic. In 1967 he

acquired a plain, unadorned Guinness-Gannon harpsichord.

John’s

marriage to Vera Slocombe broke up in 1969. By March, 1970 he was back in

Dublin, now with his companion, the viola player Ruth David. They lived

together in a very basic cottage at the foot of Djouce Mountain in Kilmacanogue, County Wicklow. There was no

running water and guests of a sensitive nature were horrified to discover that

they were expected to use sheets of newspaper when directed to a rough outdoor

privy. Every weekday John drove to the Royal Irish Academy of Music in Westland

Row, where he taught harpsichord, viol and directed a chamber music class.

Rhoda Draper and Andrew Robinson were among his viol students at

this stage. His harpsichord students included Malcolm Proud and Emer Buckley. Other students who

partook in the chamber music sessions, normally held in the Dagg Hall, included

David and John Milne, Clive Shannon, Patricia Quinn, Michael Dervan, Siobhán

Yeats and even Liam Óg Ó Floinn, who played the uilleann pipes, an instrument

that John liked very much. The traditional fiddler Nollaig Casey also

attended; John always got her to play an unaccompanied slow air at the class

concerts. A traditional flute player also performed at the concerts, though he

did not attend the class.

The famous

series of Bach Cantatas, performed during February in St Ann’s Church, Dawson Street, Dublin, under

Beckett’s direction, began in 1972 and lasted for ten years. Nicholas Anderson

of the BBC took a great interest in these Sunday afternoon concerts and several

times recorded those Cantatas that the BBC had not yet recorded. Because of

this connection, The New Irish Chamber Orchestra and The Cantata Singers,

conducted by John Beckett, were invited to perform an all-Bach concert at one

of the Proms in the Royal Albert Hall, London, on 22nd July, 1979. This was the

first time that an orchestra and choir from the Republic of Ireland performed

at one of the Proms.

The Cantata

series was revived several years after John left Ireland, with the Orchestra of

Saint Cecilia (essentially the same personnel as the New Irish Chamber

Orchestra), whose artistic director is Lindsay Armstrong.

John

regularly performed music by Haydn, notably his piano trios and songs, which

were sung by Frank Patterson and which were recorded by RTÉ radio. John founded

the Henry Purcell Consort in 1975 and brought a great deal of Purcell’s music

to Dublin audiences. He recorded an LP of Purcell songs with Frank,

re-recording some for a BBC radio programme. He also played with the Dublin

Consort of Viols (an offshoot of the Consort of Saint Sepulchre), which

specialised in the performance of works by Purcell, Byrd, Lawes, Jenkins (whose

music John adored) and other composers of that genre. He worked regularly with

the New Irish Chamber Orchestra and went with them to Italy in 1975 (where,

amazingly, he sat through an entire performance of Handel’s Messiah),

Sicly in 1977, and China in 1980, a trip that

he greatly enjoyed. He regularly tutored the annual Irish Recorder Society

courses and viol-playing sessions at An Grianán, Termonfechin, which were

organised by Theo Wyatt. By this time, he and Ruth had moved to Bray, County

Wicklow.

At around

this time in his life, John recollected a journey to the Great Blasket Island,

off the west coast of Ireland, which was made in a currach over a rough sea

during the 1940s, when the island was still inhabited. He relished the

experience of living and drinking with the locals in their rough cottages and

listened to the simple music and songs that they performed. John was well read,

loved simple ethnic pots, Byzantine icons (especially those darkened with age),

and was heavily influenced by the writings of his cousin Samuel Beckett, James

Joyce (whom Samuel had worshipped) and Kafka. He developed a liking for the

sparse, angular shapes of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, which was mirrored

in his extraordinary handwriting. The roughness and irregularity of a Japanese

tea bowl fascinated him. His two greatest treasures were a bamboo chair,

purchased in China, and an old Black Forest clock, which had been fixed by

Cathal Gannon and about which he often spoke. He also relished well-flavoured,

peasant food and had a strong penchant for garlic which he often carried in his

pocket, using the cloves to flavour his much-loved whiskey.

John

venerated James Joyce to the same extent that he worshipped J. S. Bach. Joyce’s

Ulysses was Beckett’s bible; he

claimed that he read it religiously once every year. He visited Joyce’s grave in Switzerland with

his close friend Paul Conway; they also made an extensive trip around Germany,

visiting all the places associated with Bach. He had travelled to Switzerland specifically to

see a collection of paintings by Paul Klee, an artist whom he greatly admired.

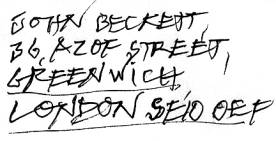

Throughout

his life, John wrote letters in his almost unreadable handwriting or banged

them out in an unchanging style on an ancient typewriter, which often was in

need of a fresh ribbon. Addresses on envelopes were often handwritten and

caused great difficulty for the postal service. His musical manuscripts were

also very difficult to read and singers often had trouble in deciphering the

words of songs.

In 1983 he

sold his house and harpsichord and left Ireland for good, moving with Ruth (and

his cat, Murray) to Greenwich in London. As his health was poor – he had

suffered a number of heart attacks – his doctor had warned him against any more

conducting. He later had a hip replaced. He worked, until he retired, for BBC

Radio 3, producing music programmes and reporting on ‘foreign’ tapes. When he

lost his beloved Ruth in 1995 and then, in December 2004, his sister Ann, he

lived alone and became somewhat reclusive and depressed. John had visited Ann

in Dublin on a regular basis and more frequently when she became ill; after she

had died, he could not be persuaded to return to Ireland and refused to attend

a reunion of the Beckett family in Dublin. The negative image that he always

seemed to have of himself – he felt somewhat overshadowed by his more famous

cousin – became more pronounced and he was inclined to be morbid. He requested

that Japanese music for the shakuhachi (an

end-blown flute) be played at his funeral. He died, sitting in his chair,

listening to his radio, on the morning of 5th February, 2007. He was discovered

by Paul Conway, who had travelled from Dublin to surprise him on his eightieth

birthday.

ASSESSMENT AND CHARACTER

John was one of the first

generation of brilliant harpsichordists that emerged in the middle of the last

century. His playing was marked by energy and ebullient rhythm, always with the

utmost clarity, and he was highly regarded as a continuo player by his

contemporaries in the UK. A most affectionate and faithful friend, John could

be a bitter opponent with a very sharp tongue. He worshipped J. S. Bach, and

held Handel, Vivaldi and Corelli in extraordinary contempt. Other favourite

composers were Mahler, Schubert, Chopin, Brahms and Fauré. He came to

appreciate the French baroque composers late in life, thanks to the

encouragement of one of his students. He disliked the sound made by some

contemporary orchestras performing baroque music on period instruments. He once

told Cathal Gannon that he would love to conduct a performance of Strauss

waltzes.

Like many conductors who are

wonderful with choirs, his relationship with orchestras was (by comparison)

slightly stand-offish. They saw little nuance in his arm movements, which

tended to be extra large; and while

orchestral players prefer to be shown things by gesture in the course of

rehearsing, John’s method was to mark each

player’s part, in great detail, in soft black pencil (having completely erased

all previous markings) in advance of the first rehearsal, and then to give

further instructions verbally. Reading his handwritten music, especially his

continuo parts, which were thick with chords, was just as difficult as reading

his handwriting.

When recording, John nearly always

delivered the goods on the first take. Very often the best buzz of all was to

be had in the final rehearsal. Despite a confident exterior, he was not at his

happiest in public performance, appearing

to scowl at the musicians when conducting.

This did not prevent him, when a performance went particularly well, from

repeating an entire Cantata at a Sunday afternoon concert.

Often regarded as a formidable,

gruff individual, he was generally a good and encouraging teacher, though he

could at times be demanding. He stretched his students to their limits, but

most were grateful to him for what he had taught them and for the fact that he

had made them play music that, without his encouragement, they would never have

tackled. Inwardly, he was very tense; it was his custom to leave for work very

early in the morning lest he get caught in traffic, which was something that he

absolutely dreaded. He regularly arrived at venues hours ahead of schedule and

the 8 o’clock rehearsals for the Bach Cantatas always began at one minute to

eight.

(Charles Gannon, Andrew Robinson,

Gillian and Lindsay Armstrong, Rhoda Draper, Paul Conway and Brigid Ferguson.)

A tribute to John Beckett by Lindsay Armstrong

John Beckett in China

Website design by Charles Gannon. Contact: cg_info@inbox.com. Updated December, 2007.