John Beckett in

China

(July–August, 1980)

On the Great Wall, 30th July, 1980: L–R:

Cathal Gannon, John Beckett,

Irene Sandford, Gillian Smith, Chinese guide, Lindsay Armstrong and Chinese

guide.

The New Irish Chamber Orchestra with John Beckett as conductor, along

with harpsichordist Gillian Smith and her husband Lindsay Armstrong, who

managed the orchestra, set off on a trip to China on 26th July, 1980, stopping for two days in Bruges,

where the orchestra performed at the beginning of the annual Flanders Festival.

‘It was a wonderful trip,’ reported John. ‘I was teaching in the Academy one

evening and the phone rang – I was down in the Dagg Hall and I came lumbering

up to the phone in the passage, and this was Lindsay, and he said ‘this is

Lindsay speaking,’ and I said ‘hello,’ and he said ‘would you like to come to

China with us?’ and I said ‘yes!’ So, that’s the way it came. I thought he was

joking, actually – I mean, I thought it was even a practical joke, but it

wasn’t.’

They arrived in Beijing at 11.30 a.m. on the 28th July. They were greeted by a large welcoming party, which included the first Irish Ambassador to China, John Campbell, and were introduced to their three guides and interpreters, Mr Liu, Miss Qing and Mr Zhou. They were driven from the airport along a tree-lined road to the centre of Beijing and brought to the Friendship Hotel, where John Beckett and Cathal shared a suite of two bedrooms, a hall and a WC. John’s rather fanciful recollection went as follows:

When we landed at Peking airport and we were taken in a bus,

and the bus drove to the kind of hostel place where we were staying, which was

terribly, terribly simple – it was like a military barracks, you know – which I

liked very much – there were no frills about it whatsoever – and drew up in a

kind of earthenware square – no, not tarred or paved at all – there was grass

growing in it – and there was a sort of hissing noise – I can remember it

distinctly getting off the bus. There was a very loud hissing noise, as if a

gas main had suddenly burst and the gas was coming out under great pressure –

sort of SSSSSS! – like that, only very loud. And I didn’t know what on

earth it was, and I asked one of our minder blokes, and he said these little

insects, they’re like locusts, which are in the trees, and when the sun comes

out on the trees, they all start to make this noise, and when the sun goes off,

they STOP! – like that. Fifty thousand of them suddenly STOP! And the children

caught them in little bamboo cages at this time… I don’t know whether that was

a particular festival or something….

But I asked one of the Chinese people what they were and he said

[‘they’re cicadas’]. He said the Chinese name, and I said ‘what does that

mean?’ And he said ‘ it means the creatures that know what’s what.’ They know

when the sun is shining and they know when the sun’s not shining, you know, and

they behave accordingly. That’s what he told me.

(John may have been aware of Henry James’s famous remark, ‘never spoil a good story for the sake of the truth’.)

Because most members of the orchestra were somewhat younger, John and Cathal were thrown together and from then on shared accommodation throughout the tour. John greatly enjoyed sharing a room (or ‘sweating together in the same room’, as he picturesquely described it) and being with Cathal; it seems that both men got on extremely well together.

In the evening, they were treated by the Ministry of Culture to a Peking roast duck banquet. Speeches were made and their host spoke warmly of the recently established diplomatic relations between Ireland and China, and how much the visit of the New Irish Chamber Orchestra would contribute to the ties of friendship and understanding between the two countries – a tired formula repeated at that time to all visiting groups to the People’s Republic of China.

They were up at half past six on the following morning; having breakfasted an hour later, they were brought to see the famous Great Wall of China and visit one of the nearby Ming Tombs.

After another early start, the orchestra began rehearsing at eight o’clock in the morning of the following day – as Lindsay Armstrong wrote in The Irish Times, ‘the earliest known rehearsal in the history of the NICO.’ The Gannon harpsichord that had been brought on the tour was down in pitch and needed a little attention from Cathal. The first concert started with music by Henry Purcell, which was probably quite unfamiliar to the Chinese audience. The audience was noisier than what the orchestra was used to – a fact commented on by both Lindsay Armstrong and John Beckett, who reported that

the concerts were all much the same

in that the venue was usually a very large hall full of people who, I certainly

had the impression, had been detailed off by the party [cadres] that they must come

to this recital, though they didn’t particularly want to. They made a terrific

noise all the time and they were getting up, you know, to get ice creams and

have a pee and doing this all the time, and talking to themselves and so on. I

just didn’t know how to deal with this and then I realised the only thing was

to just fire ahead.

I was a bit worried by this noise – I

mean, it wasn’t a hostile noise, it was just a habitual noise, and the idea of

sitting in dead silence listening to music, had never occurred to these people

at all, you know. Or so I realised later, because we were invited to a

performance, as I remember, in Peking, a kind of variety performance with

singers and even acrobats, and sword dancers and things, and there was a

terrific row going on the whole time, and nobody paid the slightest attention

to it – the performance went on, singing or talking, so I realised there was no

point in objecting to it, you know. And I didn’t and we made out.

When I at first was worried about it,

I spoke to the Chinese blokes who were managing this stage and I said ‘we’re

not going to be heard if that’s going to go on in the next concert,’ and he

said ‘well, you should be amplified – we should amplify the band.’ And I had said no to that for the first

concert, but I said yes to it subsequently. But there was no other way of doing

it – you wouldn’t have heard us at all!

The second half of the concert consisted of music by Mozart, the Irish composers Arthur Duff, John F. Larchet and four Irish folk songs sung by Irene Sandford, who wore a dazzling green gown for the occasion. She pulled the house down and sang two songs in Chinese as encores. She was finally presented with such a large floral bouquet that it was necessary for two Chinese girls to present it to her. This was another over-the-top gesture typical of the period.

On the following day, everyone enjoyed a lazy two-hour cruise around the lake of the Summer Palace in one of two covered barges pulled by a motor boat and being serenaded by Chinese student musicians, who played on traditional instruments. According to John, ‘there was a little group of musicians – there was one of these instruments with a hammer [a yang qin] – and there was one of these organs, you know, and there was a shawm, and there was the one-stringed violin [probably the two-stringed er hu], which is a most beautiful instrument, and they played extremely well. It was a bright sunny day and we were on a boat, which was provided for us –well, it seated all twenty five of us without any trouble – and up at the end on the stern was this little group of four or five musicians playing – they were very good, I thought.’ Some members of the Irish orchestra played Irish music for the students. For Cathal, it was an idyllic way to celebrate his seventieth birthday.

The orchestra was brought on a three-hour tour of the Forbidden City the next day. It could have been on this day when Cathal and John Beckett ‘were nearly arrested in Peking when John cast an envious eye on a sample of Chinese calligraphy on a rough board at the entrance to the Forbidden City [and] endeavoured to buy it!! When we returned it had been removed. He loves the rough, faded or worn.’

They were then taken to Chairman Mao’s mausoleum, which, understandably, they viewed with a certain amount of reluctance. Lunch was a more pleasant occasion; it was given by John Campbell, the Irish ambassador, in the Dowager Empress Ci Xi’s favourite eating place in the nearby palace gardens. Afterwards the ambassador, his wife, John Beckett and Cathal walked through the oldest part of Beijing, which sadly was about to be demolished and replaced by apartment blocks.

The concert that evening was televised and was a great success. John Campbell was brought back to the Friendship Hotel for supper afterwards.

As the following day was Sunday, the orchestra was allowed to spend ten minutes in the Catholic cathedral, which was filling up for Mass. They found quite a number of people there. They were introduced to the priest, who spoke to them briefly and asked them to take greetings back to Ireland. The orchestra was then brought to the famous and beautiful Temple of Heaven, which they saw before leaving for the airport and Chengdu.

After a three-hour flight, they arrived to flowers and greetings from members of the Arts Bureau and professors and students of the Chengdu Music Conservatoire. The Professor of Composition, who did not speak a word of English, wondered if Irene Sandford could sing ‘The Last Rose of Summer’. In the evening they attended a reception, where they met the leading cultural and musical people. None of them had ever seen a harpsichord before. The reception lasted from 7.30 to 10 p.m. and continued for another hour in Lindsay Armstrong’s room.

On the following morning Cathal, John Beckett and Betty Sullivan slipped out of the hotel, avoiding the guides and went walking ‘in the old part of this most interesting town. We met all the people young and old, took snaps and had our breakfast in a little native restaurant.’ John managed to buy the chopsticks with which he had eaten his breakfast. From now on, he and Cathal managed to escape the crippling officialdom and regularly went out on their own in the mornings amongst the people, much to the consternation of the guides, who reprimanded John for not obeying their rules.

The concert hall in Chengdu held 3,200 people and the acoustics were very dry. As there was no air conditioning, electric fans were produced. The orchestra rehearsed in the morning and in the afternoon there was some more sightseeing.

Despite the heat and the electric fans ‘blowing full blast over great blocks of ice’, the concert that evening was a great success.

Cathal was up early again the next morning and out in the streets with John Beckett. John relished seeing the local people doing their morning exercises under the trees, the children attending to their homework outside their little houses, people eating and men having their hair cut on the street. The first official business of the day was a visit to the zoo, where they saw pandas and a white peacock. Next they were taken to the Chengdu Music Conservatoire, where they met the professors and students. As they had never seen a harpsichord before, Cathal promised to send them plans and examples of jacks. John Beckett and the various members of the orchestra were suitably impressed by the students’ high standard of playing and the excellence of their teachers. In the afternoon they were brought to a Buddhist monastery that housed thirty-two monks. There they were given tea and had various questions answered, though some not very convincingly.

At the concert that evening, the orchestra finally agreed to be amplified in order that they might be heard better in the huge hall above the chatter of the audience.

Cathal and John went out the next morning to meet some new friends that John had made: a young man who called himself Martin Mao and spoke good English, and his girlfriend (whom he later married). John subsequently corresponded with the couple and later Martin’s wife visited him in London when she was there. John and Cathal had ‘a snack’ with them that morning, walked around and returned to the hotel for breakfast. It was possibly on this morning when John succeeded in buying a bamboo chair for himself in a shop where he found an elderly man making chairs. This light, practical chair, which was cleverly constructed without nails, was, in John’s estimation, the best souvenir that he brought home from China. On flying home, it was tied with string to the stool for the double bass and treated as if it were part of the orchestral equipment. It lasted for many years and, as John reported, improved with age. ‘When it gets my vast weight on it,’ he said, ‘it gives a bit of a groan, but actually it keeps it in good condition, you know.’

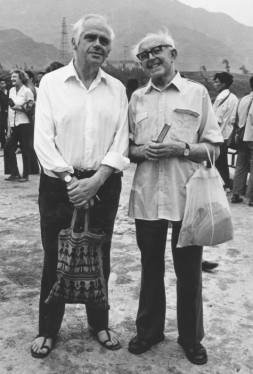

John (left) and Cathal

Gannon in Dujiangyan.

Later that morning they were taken to the Dujiangyan dam and irrigation system, which had been dug some two thousand years previously, and which lay twenty-five miles outside Chengdu. They visited some adjacent temples and were given a ‘wonderful lunch with many toasts. We were nearly all tipsy,’ as Cathal reported. Much to John’s chagrin, bamboo chairs identical to the one he had bought in Chengdu were being sold locally for a few yuan cheaper than for what he had paid.

As it had been a long day, the orchestra was happy to perform just one third of a concert in the evening; it included Irene Sandford singing ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ and ‘Molly Malone’. Afterwards they were treated to a concert of traditional and classical music given by Chinese musicians; Cathal recorded that two Preludes by Chopin were performed on the piano. Following this came an excerpt from a Chengdu opera, ‘clappers and all’, during which most of the young people left the hall. Cathal was sad to observe that the younger generation had little or no interest in their traditional entertainment; he and John relished it.

The group left Chengdu at 6.15 on the following morning for the flight to Xi’an, once a very cosmopolitan capital of China. They arrived three hours later and were installed in the People’s Hotel.

In the evening they were taken to a three-hour-long classical Xi’an opera, which ‘at times was hard going. The costumes were exquisite, the acting fine. We had an interpreter who helped us with the plot.’ Lindsay Armstrong noted that there was a lull in the translation of the story for quite some time. He turned around to discover the interpreter lying slumped in his seat fast asleep, ‘presumably from linguistic exhaustion’. The performance

took place in [one of] those provincial cinemas, built, in

the early thirties, of concrete, which are now all falling to bits, you know.

It went on all evening: a long, complicated story of court intrigue, centuries

ago; [the actors were] heavily made up and singing in very stylised voices and

speaking in very stylised voices, depending on the rank of the person they were

talking to. I mean, it was absolutely marvellous. And a gang of musicians,

traditional instruments, flutes and reed instruments, and these things and

drums – a lot of percussion – in a little kind of caged-in place on the right

of the stage, belting away for all they were worth, without any sense of

balance at all. And the characters of the text were projected with slides, and

so most of the audience were like this [looking to one side], because you could

not hear what they [were singing], and the noise of the orchestra was

tremendous! The hall was absolutely

full, and there were old people…. I could really hardly believe I was there –

it seemed incredible to be sitting in [the] slums [of] some city in the centre

of China, with a crowded audience on a sweltering hot summer night, seeing and

listening to this! But, again, the noise of the audience was tremendous.

Unforgettable! And it was wonderful – it was very good. Really, I can’t judge

because I’m not quite sure what’s good and all that sort of thing and what

isn’t, but it thrilled me, absolutely.

Lindsay noted that the whole musical framework of the opera was held together by the main percussionist who played unceasingly, from memory, throughout the entire performance. When they met the members of the orchestra afterwards, the percussionist told them that it had taken him three years to learn the work.

On the following morning, the group was brought to see the city walls, a museum and to two pagodas. They rested in the afternoon and then Cathal and John walked through the old parts of the city, where John bought two bowls from a small restaurant. Cathal then brought John to the Shaanxi Provincial Museum, which he had obviously missed, and showed him the Tang Dynasty glazed pottery figures. There they met a group of students, who promised to bring John to a pottery shop. In the evening, they were taken to the veranda of a tea house in a quiet park, where they sat by a beautiful lake sipping tea and beer in the darkness of a balmy evening. A sing-song began; one of the guides, Miss Qing, obliged with ‘My Bonnie lies over the Ocean’. By the time they returned to the hotel, John was already there, having bought another six bowls.

The highlight of the tour came on the following morning, when the group was brought to see the excavations at the imperial tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the great emperor and tyrannical founder of the Qin Dynasty in 221 BC. Here they saw the buried army of some six thousand terracotta soldiers that had become famous throughout the world. The excavation work was far from complete and both Cathal and John saw more statues being unearthed. Cathal was quite overawed and wrote that the tomb was ‘a most impressive sight which I shall never forget.’

In the afternoon, Cathal tuned the harpsichord, which he reported to be ‘behaving excellently’ and another highly successful concert was given that evening.

The next morning was devoted to a get-together with the musicians from the Art School in Xi’an, who, according to Cathal ‘were very appreciative of the help and advice given by members of NICO.’ Both he and Lindsay Armstrong recorded the great interest shown in the harpsichord. To demonstrate it, John played the accompaniment of a Tartini violin sonata after the violinist’s wife had played the accompaniment on the piano; it was ‘a revelation’ for both the students and teachers. Two of the violinists, Mary Gallagher and Thérèse Timoney, joined forces with John Beckett and Betty Sullivan to play a Bach Trio Sonata, which ‘went down very well’.

Breaking all the rules, the orchestra arrived back at the hotel almost an hour and a half late for lunch. In the afternoon they rested and later were taken to a lacquer and jade factory – ‘awful’ as Cathal succinctly described it. In the evening the final concert was given – it was a great success. According to Lindsay, Irene Sandford sang better than ever and he added mischievously, ‘even a twitch of a smile [was] seen around the corners of John’s mouth’.

Cathal’s record for the next day began with a description of being out by seven o’clock with John, Jacques Leydier and Irene Sandford to watch the locals doing ‘sword exercises’ and walking until breakfast at nine. An hour later they were on their way to the Neolithic museum and village of Panpo. They rested after lunch and later John and he went ambling around the old part of the city, which Cathal found most interesting. After they had started to pack for the following morning, they sat down for the official farewell dinner, which featured ‘many toasts with important people present’. Lindsay made a speech that he had written during the afternoon, and was complimented by Mr Zhou, who requested a copy ‘as an example of English literary style’, by which, Lindsay surmised, he meant good English style. Afterwards they adjourned to John Campbell’s suite in the hotel for after-dinner drinks.

Early in the morning of the 12th August, the orchestra set off by plane to Beijing. They were escorted to a VIP lounge, where they left their luggage and instruments and then, in the appropriately named ‘Ever Green’ restaurant in town, they hosted a banquet for their guides and the friends that they had met in Beijing. They visited another Friendship Store and finally returned to the airport, where gifts were presented to their guides. After an emotional farewell, during which Miss Qing burst into tears (not an uncommon occurrence at that time owing to the harshness of life during and after the Cultural Revolution), they boarded the aircraft and soared off into the darkening sky.

(Based on extracts from the full, unabridged version of Cathal Gannon – The Life and Times of a

Dublin Craftsman, by Charles Gannon, and an interview with John Beckett by

the author, recorded in July 1998.)