It may not have occurred to you but the making of the violin family of instruments was at its peak in the eighteenth century. Probably all other instruments, be they woodwind, brass, percussion or fretted string may not yet have 'peaked'.

If money is not your problem and you want the very best violin then try to get an eighteenth century one or one as old as possible. If you want the very best woodwind instrument or brass instrument buy a recently made one as the older ones are not as good.

As someone who has studied the art and craft of violin making it always fascinated me as to how this happened. Using modern technology, frequency counters and the like it always shows that the Old Masters got it right. How they did this with just hand tools and no technology is quite amazing and adds to the mystique of the art. A lot has been written about how Antonio Stradivari held the secret of the varnish, then it was Amati, they say, who used a mallet to strike the tree before it was felled and would only select a tree that 'sounded true'. I don't intend to dispel any of those myths but Stradavarius may have had a very good recipe for his varnish, what it most likely did was not to dull the tone as much as lesser varnishes. As for Amati, I suspect that he did not want to go to the trouble and expense of felling a tree that had a rotten core and he could detect this by striking it with a mallet! We will probably never know.

Amati, the only information that I could find on the www at the moment referring to the Amati family can be seen by using the link above. It is interesting to read even though little is said about the Amatis. The instrument that they are describing is a 'viola de gamba'. This instrument is a bowed instrument but it differs from the violin family in that the body shape is different, slightly, and the fingerboard is 'fretted' with tied on gut frets. This requires a lot of care and tuning as if the 'frets' are moved, even slightly, the frequency of the note will be changed, or put out of tune to put it bluntly. The viola de gamba is a 'cello sized instrument but it does not have a 'spike' to support it. The playing position is to clutch it between the knees and calves and it is played in a more upright position than a 'cello. In addition the bow is a 'bowed' bow unlike the 'modern' bow which has a concave stick. The viol family may become the subject of another page, they are a fascinating instrument with a long history. I have heard viols played and they have a much lighter tone than violins or the violin family. Just another taste of bowed string music.

Stradivari lived to be about eighty five years old and worked all his life making instruments. Some would say that he probably had to as he had many children and needed to keep working to feed and cloth them all. It is generally accepted that the instruments he made in midlife were probably his best. These would date from about 1740 and it is quite amazing that many of them still exist. Sadly, they now change hands for huge sums of money to such an extent that very few players can afford to have one. It is a pity that they are just languishing in the vaults of banks and such places. I was lucky enough to have once had a Stradivari viola in my hands and to hear it being played by its owner who lived here in Cork. That same person played one of my violins and was very complimentary with his remarks. I must say that he made it sound extremely well.

Note:If you have looked at the link to the 'Stradivari' website indicated above you will see where it is claimed that Stradivari only made one violin a year. I don't think that this is true at all. If my recollection serves me well I remember reading that at one time in his life he was 'making' one violin a week! This would be a physical impossibility for any person working to such exacting standards. Then when you consider that in 'those days' it was suggested that you could not varnish a violin between the months of October and April as the climate in Cremona was such that there would be too much moisture in the air for the varnish to cure properly. But apart from that Stradivari had 'helpers', perhaps his children, of which he had many, or apprentices working for him and being trained by him. He probably had a 'conveyer' system of production going that allowed him to 'take over' and 'finish off' each piece to his own exacting standards. I think that this is a credible story. Such were the demands for instruments at the time that 'mass production' of some sort was required. It would be not unusual for the local Doge or Bishop to order a chest of 'viols' for his own entertainment. This chest could consist of a 'cello, viola and two or more violins, all matching in detail, colour and finish. If one had to wait five years for such a chest of instruments I feel that business would migrate to another maker.

Another very important thing that was not mentioned is that the neck of the 'modern' violin is longer than the neck of the instruments made by the Masters. This means that the 'stop' is now longer. The reason for this is that the strings now used are of metal and woven metal with a core made of a type of nylon cord. This means that the strings have to be tensioned more to get them 'up to tune' - modern concert pitch - A is pitched at a frequency of 440. That is a full tone or a tone and a half higher than with the old instruments and opened up the possibilities of the instrument making more advanced music possible. As a matter of fact all Stradivari instruments and instruments of that era that are still played today have a neck graft done. This involves cutting a segment out of the neck and grafting in a piece of new timber. This also means that the finger board has to be replaced to cope with the longer stop and neck. I'm told, and have read, that such old instruments, when bought from a valid source will have the 'cut out' piece of neck and old finger board included with them to add to authenticity. If the new owner really wanted to the instrument could be 'restored' to the original. Another very interesting thing about these instruments is that they can be completely dismantled or taken apart and rebuilt. The procedure is reversible. I have done it to a limited degree. Apparently this is a feature that has a very impressive name but sadly, like so much else, I can't recall it. But back to the tuning fork. Look at a tuning fork and you will see the number 440 stamped on it. Of course, and just to be different the German Philharmonic Orchestra, when under the baton of Herbert Von Karagan tuned to 441! Was there a valid reason or just an idiosyncrasy, the latter would be my guess.

If you have delved into the Stradivari link be sure to delve further. There is a very interesting interview with a fellow called Joseph Nagyvary. The article was published in the Scientific American and is well worth reading. Be sure not to miss parts of the interview, it is not very well laid out on the page and is easy to miss that which is written on the bottom of the page. There are some MP3 files available there where you can sample three pieces played on a genuine Strad and then the same pieces played on recent instrument made by Joseph Nagyvary. He has done a very scientific study of violin making and is convinced that he has 'cracked' the secrets of Stradivari.

The only other instrument of that era and quality that I have heard being played was a double bass, made by Amati in 1611, as far as I can remember. It was owned by Gary Karr the American exponent of the double bass. He gave a recital here in Cork about twenty years ago and it was there that I heard him. He is a very extrovert person and certainly puts on a good 'show' but the purists among us cringed a little at some of his 'antics'. That may not be a very fair comment, my own 'criticism' of him was that most of the pieces that he played sounded like as if it was on a 'cello that they were being played. He used a lot of harmonics, which is a testimony to his skills but why use a bass instrument and play it at the upper extremes of its and the players ability. It was a very pleasant evening and he told the story of how he 'got' the instrument too. I am including a link to his website if you wish to read a little more about him and to listen to him playing. Just click on Gary Karr and wait.

To make a violin as one of the old master would have done is a long and labourious process. Most people don't realise that a violin is made from a number of woods. The front is made from two pieces of close grained pine quarter sawn; the back from two pieces of maple, usually quarter sawn. The neck is made from maple and the finger board and tail piece are made from ebony or rosewood or some such hardwood. It is essential to have a hardwood for the finger board as any soft wood would wear too easily. The nut between the pegbox and the finger board is usually made from the same hardwood as the finger board although it is not unusual to see it made from bone (don't mention ivory), likewise the nut at the base of the instrument is usually made to match the nut at the pegbox end. The endpin, used to anchor the tailpiece is also made from hardwood as are the four pegs for tuning the strings. Inside the instrument the bass bar and sound post are made of pine as is the neckblock and the tail block and the four corner blocks. Willow is used as 'linings' to reinforce the six 'bouts'. On the outside the inlay is called purfling and this is usually made from a sandwich of willow between two thin pieces of ebony. The last piece of wood on the instrument is the bridge and this is cut from maple. The total number of pieces of wood to be fashioned by the luthier to make a violin is seventy seven! Now if you wanted to make a copy of an Amati you would have to have double purfling on the front and this would bring the total to a higher number.

Why or how did I ever start violin making?

The answer to that is simple. I always liked to make things and to repair things and when the opportunity presented itself to me and the need arose I studied the craft. Our five daughters all learned music and all played bowed string instruments. Three of them played violin and two played 'cello or violoncello to give it its full name. I didn't attempt to make instruments for them as life is not long enough but the need arose, from time to time to replace bridges and to reshape fingerboards and to service pegs. To make a long story short I joined a class in violin making and two years later had my first violin made. By then I was repairing instruments for friends and colleagues of my daughters and eventually had to start charging as I was spending so much of my time doing it. This put pressures on me that I didn't want and within a short time I eased myself out of it. I was also approaching that time in life when I had to start wearing spectacles for close work and this interfered greatly with the ease with which I could formerly work and it ceased to be enjoyable. I have no regrets, I learned a lot and developed my woodworking skills to a point that I didn't think I could. I also learned a lot about sharpening tools as the sharper the tool the easier and better the work will be. I also learned a lot about string instruments but sadly never managed to play one. In addition to the instrument making side of the business I learned how to service and restring bows and was in great demand for this service until my source of horse hair ceased with the death of a very nice man in England from whom I got my supplies. He was a 'horsehair dresser' and did nothing else. He died and the business died with him. I had a very nice letter from his brother notifying me of the death, he wrote to all the people that were in his brother's address book. I appreciated being notified, I never met the man but felt that I knew him as we had exchanged notes every time I would order some hair.

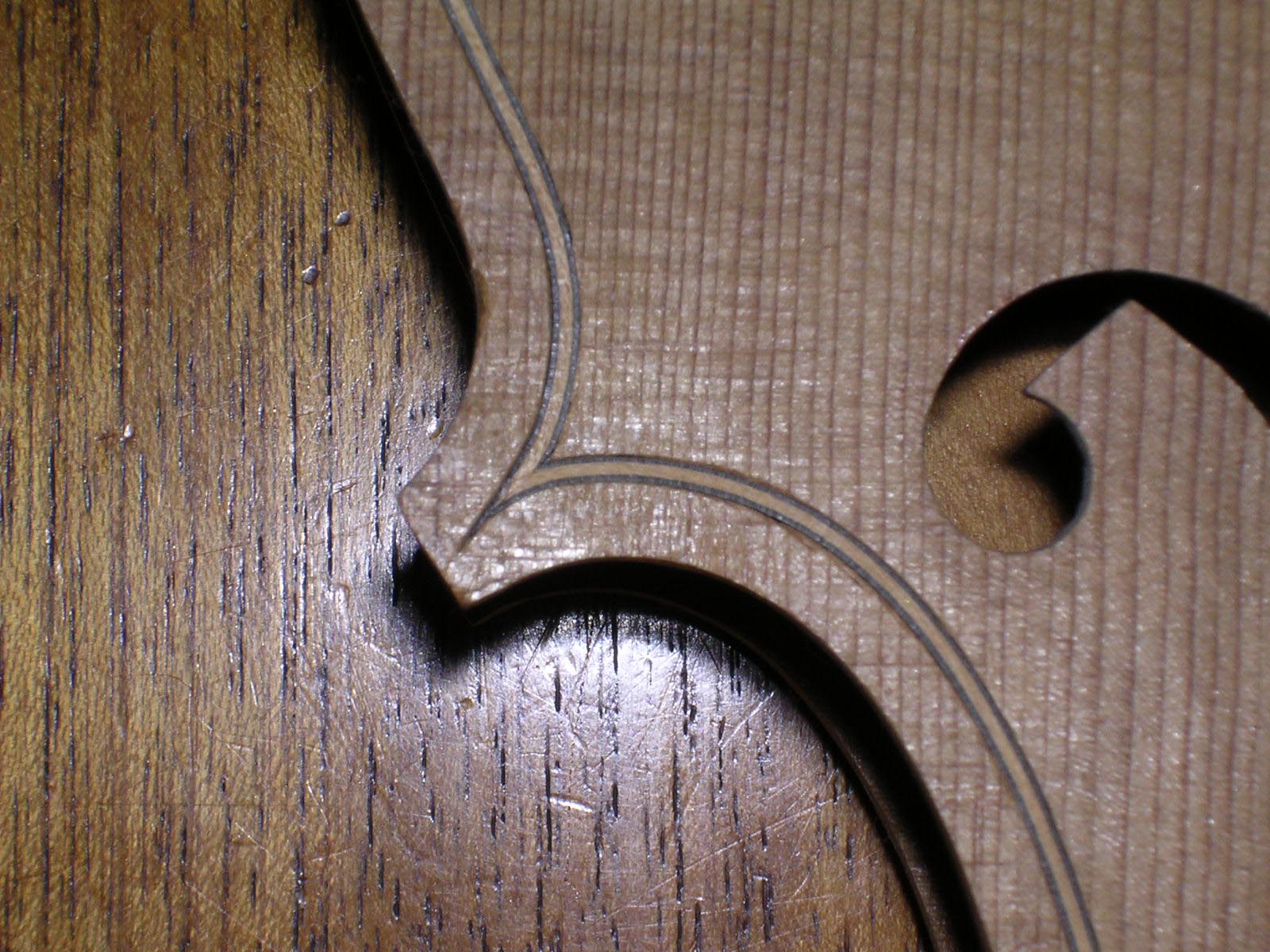

The three photographs illustrating this page are of a violin in the process of being made. The top photo is of the 'pegbox' of the neck. Note the intricate carving of the scroll, the holes for the four pegs have not yet been drilled and reamed. The middle photo is a detail of the 'bee sting' at the 'C' bout. This is the detail of where the purfling from the two joining curves meet. One piece of the three woods is carried over the adjoining three pieces of inlay to give a 'bee sting' effect. Next time you have a violin in your hands look out for this. The accuracy with which this is executed will give you a hint at the quality of the instrument. In all humility I must admit that I am very pleased at how well I have executed the 'bee sting' shown. The bottom photo is of the 'f hole' of the violin. The style of the 'F' holes varies from maker to maker and from period to period for each maker. The experts can date a violin and determine the maker from the 'F' holes. Again I am very pleased at how well I have cut the 'F' hole shown, a rather good 'Stradavarius' copy. On a good instrument these will be very accurately cut. Many may not know that the two notches in each F hole are not just for decoration, the notch to the outer side of the F hole is decoration but the inner notch actually marks where the bridge should be positioned. This is critical to establish the 'stop' of the string. To have any standard between instruments it is necessary to have the distance from the nut at the peg box to the bridge the same. This distance is known as the stop. When the bridge is positioned the sound post can then be properly sited as that is not a support for the front of the instrument, it plays an essential part in conveying the vibrations of the strings to the back of the instrument. The arching of the front of the instrument is such, much like the arch of a bridge, that it can support the tension of the strings on the bridge without the sound post. Played like this the instrument would sound like any other timber box. The pressure that the strings exert on the bridge and the front of the instrument, when fully tuned, is about thirty five kilograms. The instrument will not be varnished until it has the neck attached and the trimming of the purfling is completed. All three photographs are from an instrument that I have yet to complete.

An excellent and interesting source on violin making and the science and mathematics involved can be found in a book, written by Edward Heron-Allen, it is called 'Violin Making as it was and is'.