|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

History of Mooncoin

| Index |

| Early History (1100 - 1650s) |

| Counter-Reformation (1700+) |

| 1821 Census & Genealogy |

| Carrigan's History of Mooncoin |

| Sinnott's Cross Ambush |

| Carrigeen Affray 1832/Watt Murphy |

| Old Schools |

| Mass Bush |

(Click on your choice from the above index)

|

Eamon de Valera outside the Church gates in Mooncoin village in June 1922 during the final week of 'Pact' general election campaign. The aim of his speech in Mooncoin was to attempt to get the people to support 'the pact' candidates in the upcoming election. This was an agreement himself and Michael Collins had agreed to stop the country slipping into civil war. The idea of the pact was to form some kind of 'power sharing' after the election between people who supported the Treaty and those that did not. The resulting election did not go this way, and civil war broke out just three weeks after De Valera and Cathal Brugha had been in Mooncoin. Eamon De Valera had previously come to Mooncoin in March 1918 with Arthur Griffith for a meeting after the Waterford by-election. |

History begins with the earliest written records related to the area. However, it is worth remembering that there is unwritten history in still part of the landscape. For example, the 'fairyforts' in the parish e.g. in Tubrid, were early farming houses, dating from cir 400AD (now home of the fairies of course!). So our ancestors would have built up a mound of earth, fortified it and built a dwelling house, of which usually only some of the mound remains in the landscape. They usually were on elevated ground so the inhabitants had a good view of the area. Any cattle would have been brought back into the fort or rath at night for their protection. There is estimated to be around 45k 'fairyforts' in Ireland. However, as there has been no excavations on these prehistoric farms in the locality, we need to start with the written history.

One of the earliest recorded pieces of information in relation to Mooncoin is in the 'Catalogue Of the Bishops of Ossory' (British Museum - London). It states that in circa 1240, the Bishop of Ossory (De Turville) 'acquired a wood near Clonmore'. We now believe that this wood is where Kilnaspic is currently, and subsequently where 'Kilnaspic' got its name i.e.Coill-na-Easpag - 'the Bishops Wood'. Owning woods was a major source of income. The trees would be felled and sold, sometimes for ship building. It would have been illegal for any of the locals to cut down trees or hunt game in the Bishop's wood.

So, ironically, the name 'Kilnaspic' has nothing to do with a church, in this instance its a wood. It only became a church site much later. 'Kill' is usually the anglicised version of the Irish word for church, 'Cill'. The Bishop of Ossory owned a lot of land in Clonmore also, and this is the reason we have these records. In 1460 Bishop Hackett built a mansion in Clonmore along the banks of the Suir. It was more or less a holiday home he could retire to from Kilkenny City during the summer months, most likely by taking a boat down the Nore and back up the Suir (it was on the site of Clonmore House - 'Morris's').

The current parish of Mooncoin is generally referred to as the 'Burgagery of Rathkieran' in these early Ossory records of cir 1200 (in many records right up until the 1800s, what we now know as the parish of Mooncoin is actually referred to as the 'Parish of Rathkieran'). This was because the main parish church was in Rathkieran for hundreds of years. In fact, there is a record of Donnail O'Fogertach, then Bishop of Ossory, being buried in Rathkieran graveyard on the 8th May 1178. At the time there were monks based here. So the Bishop may have been just visiting or being cared for here and passed away. Or perhaps, he was originally from the Mooncoin/Rathkieran parish area and requested to be buried there. This early church and monastery has long since disappeared and there seems to have been a number of churches built on the site. The church ruins currently in Rathkieran are of the Protestant church, rebuilt and re-roofed in 1727 (this church was knocked around 1880 with just an arch now remaining) - however this church is recorded as being nearly identical to the previous Catholic church. There is also evidence that pre 1118, Rathkieran was its own holy sea, that is, it was its own sub-diocese and was absorbed into Ossory after this date. About 200 yards north east of Rathkieran, near Ashgrove, there is a Rath or hill/mound called 'the Corrig'. This is where the monks attached to Rathkieran church were said to have had their residence 1000 years ago. A holy well is also located close by in Ashgrove. Any place names in Ossory with 'Kieran' are usually very old as St Ciaran/Kieran was the man who is said to have brought Christianity to Ossory in the late 5th century. He is the patron saint of the diocese and considered the first Irish born saint.

It is worth remembering that any church that existed in the parish at the time of the Reformation of the 1540s, would have been re consecrated as Protestant churches (Anglican/Church of Ireland) quite literally overnight. Church of Ireland became the official state church, the King replacing the Pope as head of this new state church. Conversion rates, however, were very low in Ireland. There followed the building of multiple churches in the newly established civil parishes to encourage the locals to join the new state religion. There would literally be a church on your doorstep. In fact, what is now Mooncoin Catholic parish, was made up of five separate sub parishes, with a church in each of these sub-parishes (also known as civil parishes). These were; Rathkieran (the main church), Aglish/Portnascully, Tubrid, Polerone, Ballytarsney and Clonmore. Ardera was later its own Civil parish. There was also a private church, likely built by the Bowers family, known as 'Kilaspy' (not to be confused with Kilnaspic) - although there is evidence that a church existed on this site in medieval times also. The ruins of this church are located in a field in Grange near Silverspring. Also, Polerone Church ruins can still be seen near the River Suir (Church of Ireland); some church ruins and graveyard are still in existence in Rathkieran (Church of Ireland); some foundation ruins and headstones of Tubrid can be accessed through a field; Aglish is mostly gone but the later Portnascully church still is visible.The most recent Church of Ireland church built was Graigavine church near Cloncunny/Emil, which was in Clonmore civil parish. It served members of the Church of Ireland faith from 1818 to 1906 after the other five Church of Ireland churches had closed down. Surprisingly, considering there were at one stage between 5 and 6 Church of Ireland churches in Mooncoin, there are none currently remaining. Graigavine lasted less than ninety years, with the Church of Ireland parishioners then having to worship in Piltown (the roof and walls of Graigavine were mostly removed in the 1960s).

There were some slight differences between the Roman Catholic parish used today (made up of Kilnaspic, Mooncoin and Carrigeen) and the civil parishes; in that, some don't overlap. For example, the townland of Cashel is in the current Roman Catholic parish of Mooncoin, but the Civil parish of Fiddown (now in Templeorum Parish). Likewise, some parts of the current Kilmacow Catholic parish were under Rathkieran civil parish.

Outside of church history, we know the main landowners in the area from cir 1400 were the Butlers of Grannagh (Granny) Castle - (who were a branch of the Butler family based in Kilkenny Castle). In later years, the Earl of Bessborough based in Kildalton, Piltown, was the main landowner in the Barony of Iverk. The Barony of Iverk took in the modern parishes of Mooncoin, Kilmacow, Piltown and Fiddown. The barony originally consisted of 41,369 acres and got its name, 'Uibh Eire', the 'descendants of Ere' from an ancient sept/family. Originally the main seat of power for Iverk was Granagh castle and later Bessborough in Piltown (the Bessborough estate still owned cir 25,000 acres by 1875).

Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland

There is also detailed information surviving in relation to Mooncoin from the 1650s when Oliver Cromwell and his army conquered Ireland and subsequently made official records when locals were transplanted. Folklore has it that Oliver Cromwell passed close to Mooncoin after taking control of Wexford Town and New Ross. He came over the Walsh mountains and on looking down on Mooncoin and the surrounding area is reputed to have said; "This is land worth fighting for".

Firstly, some background to Cromwell's 'conquest' of Ireland. There was a rebellion in Ireland, mainly in Ulster, in 1641 were many Protestants planters were killed by the local Irish (cir 5000 killed). There was roughly the same number of Catholics killed in retaliation. The tabloid news-sheets in London greatly exaggerating the number of Protestant settlers killed. Cromwell saw his invasion in 1649 as revenge against the 'barbarous Irish wretches' for these acts committed in 1641. He also needed to regain control of the country as there was a Confederation (type of government) in Kilkenny City which was governing most of the country. The Confederation of Kilkenny was made up of a mixture of Catholic and Protestant members loyal to the King of England (Charles I) whom Cromwell had arrested and eventually executed. When Cromwell sailed for Ireland, it was his first time ever leaving England and he arrived (with severe seasickness) in Ringsend, Dublin in August 1649.

Cromwell is most infamous in Ireland for the mass murder of civilians in Drogheda, Co Louth, where 3000 men, women and children were massacred (this occurred on Sept 11, 1649, their own '9/11'). The dead were mostly Catholic. Even at the time it was considered shocking, as women, children and the elderly were usually spared in 17th century warfare. He was also accused of not giving 'quarter'. This is when people surrender, they are meant to be spared and taken prisoner. Cromwell felt however he was doing God's work, and that God was on his side. The only town that gained any success was Clonmel. Here Cromwell lost around 2,000 men.

Soon after Cromwell's conquest of Ireland he started a policy of 'transplantation'. This involved moving the native landowners, who had not sided with him, to western counties (where the land was poorer; "to hell or to Connaught"). This was decided under the 'Act of Settlement'. To pay the wage bill of Cromwell's army who were in Ireland since 1649, it was decided to pay them with land from the conquered Irish, as opposed to actual money which was scarce. At one stage the leadership in Dublin and London were pushing to remove all catholics to Connaught. However, it was then decided to move just land owning catholics and give them a third to two thirds in value, of their conquered land, in Connaught. Poorer catholics and labourers stayed put, so to work the land for their new landlords. Protestants already based in Connaught had the option of exchanging their land for better land in Leinster or Munster. All catholic priests were also told to leave the country. A man who had supplied thousands of horses for Cromwell was given vast tracks of lands in south Kilkenny, Tipperary and Carlow for his payment. He was known as Ponsonby, but the family later received the title the 'Earls of Bessborough'.

Here is an extract from the official documentation in London dated April 1653:

They (Catholic landowners) have until 1st of May 1654 to remove and transplant themselves into the province of Connaught and the county of Clare, or one of them there to inhabit and abide.

In January 1654, in Grocers Hall, London, representatives of adventures and soldiers met to draw lots on which land they would take in Ireland. A kind of a lucky dip depending on rank etc.

When local families were to be transplanted, the man of the family had firstly to go to Loughrea, Co Galway. Loughrea was the centre of administration for the transplantation. Here he had to register and stake provisional claim and throw up a shack. He then returned for his family and 'cattels' (mainly 'black cattle and horses'). However many families could not meet the 1st of May 1654 deadline and so applied for extensions. Some were granted, which allowed the women and children to stay behind in Kilkenny in the summer of 1654 to harvest crops. However, they had to give a lot of these crops to the new landowners as compensation. All of the native Irish outside their own locality had to carry identity cards to facilitate the upheaval.

Mooncoin

did not escape this transplantation plan. It is worth noting that 58% of the land in County Kilkenny was confiscated and given to the Cromwellian/parliamentarian soldiers. Some evidence of this upheaval is still on the Mooncoin landscape today with the ruins of Corluddy castle and Grange castle whose owners, the Grants and the Walshs respectively, moving to Connaught in 1653. It is hard to imagine the trauma these people went through at this time. Many would have been old and had to make the hard journey to Galway on foot, or horse if lucky, never to see Mooncoin or their old homes again. Just a few years before, Kilkenny City had been prosperous and the 'capital' of Ireland, with the local economy doing extremely well. Closer to home, just five years previously, the Walsh family that lived in Grange Castle had hosted the Papal Nuncio from Rome which was a huge privilege. The Papal Nuncio would have been one of the most powerful and influential people in Europe at the time. Now the family of seven were on their way to Connaught. Some decades later, the Grants had 200 acres in Galway, less than 20% of what they would have had in Mooncoin.

Here is an extract from certificates granted to the

native Mooncoin people transplanted from the Mooncoin area (1653-1655) - Cromwellian soldiers would have taken over their land in Mooncoin, perhaps subleased from Ponsonby. Note: the different families with the name of 'Grant' were all related in some way. So they were all 'tarred with the one brush'. 'Glengrant' got its name from this family. Also note: place spelling is how it was written at the time:

|

Name

|

Townland

|

Number of People

|

| Donnagh Brenane | Ardragh | 9 persons in all |

| Walter Dalton | Rathcurby | 20 persons in all |

| David Egnott (Synott) | Aghlish | 7 persons in all |

| Edmond Grant | Polroane (Castle) | 14 persons in all |

| David Grant | Corlodie (Castle) | 21 persons in all |

| Edmond Grant | Dunguoly | 15 persons in all |

| Ellen Grant | Ballynabouly | 14 persons in all |

| Thomas Grant | Ballynabouly | 6 persons in all(Forfeit Caste) |

| Thomas Purcell | Ballysallagh | 16 persons in all |

| Helias Shea | Clonmore | 5 persons in all |

| Oliver Wailsh | Grange (Castle) | 7 persons in all |

| Rich Wailsh | Killcragganstown | 6 persons in all |

| Thomas Wailsh | Ardry | 25 persons in all |

| William Wailsh | Barribahine | 8 persons in all |

| Pierce Dalton | Ballynecrony | 12 persons in all |

| Philip Henbury | Fanningstown | 6 persons in all |

| Philip Kelly | Jamestown | 15 persons in all |

| Ellen Sweetman | Ballyferrickle | 11 persons in all |

| Piers Wailsh | Ballyferrickle | 3 persons in all |

| Robert Wailsh | Unnige | 10 persons in all |

| Edward Wailsh | Listorline | 7 persons in all |

| James Wailsh | Corbehy | 11 persons in all |

| Edmond Wall | Bananagh | 9 persons in all |

| Patrick Waldon | Killdarton | 13 persons in all |

The Protestant churches in the parish found it very hard to survive as the population of the Protestant community continued to be very low. After the Reformation, the idea was that the Catholic population would decline and the Protestant population would increase as people converted to avoid the harsh penalties. Thus, after a few generations the Catholics would be a minority. Conversion figures in England and Wales were high but they failed to take into account Irish peoples perseverance (/stubbornness)! Even after the most stringent anti-Catholic laws were introduced - the Penal Laws which came into being between 1690 and 1710 - the Catholic inhabitants of Mooncoin still refused to convert. Where a Catholic priest could be found, Mass was usually celebrated outdoors at a 'Mass bush' or 'Mass rock'. For example, there was a Mass rock near Polerone, and Mass trees in Tubrid, Carrigeen and Ardera. Religious service was infrequent then for Catholics, with just baptisms, marriages and funerals the only contact with priests. When a priest would turn up on a visit to the parish, there would have been a huge amount of baptisms, blessings and marriages taking place, likely some at the same time. When a Catholic parishioner died, they usually got permission from the local vicar to be buried in the Protestant church grounds. In likes of Rathkieran, their ancestors would have been buried in the graveyard, so although the religion had changed, the families usually were permitted to be buried in the family plot. Records show that in 1776 - just as the Penal laws began to be relaxed - the Vicar in Portnascully parish only had three members in his congregation, compared to 433 Catholics who lived in that parish. It is also likely some Catholics attended service or held funerals in Protestant churches as they had no church of their own. So it would be considered a 'grey' area with many of the local vicars turning a 'blind eye' to the Catholics attending their service.

There was no physical Catholic places of worship in the parish until 1752, when the Catholic Church started to reemerge. Then we have a record that a 'Mass house' was built in Kilnaspic. Catholics were not allowed to have 'churches' per se, so a stone or wooden thatched house was used to circumvent the law i.e. it wasn't a church, but basically something resembling a barn. The first thing that comes to mind is how remote the location was. It was on the far side of a hill and certainly quite hidden and not in peoples face (it was located just down the hill from the current church in Kilnaspic - at the end of the current graveyard). This is how most new Catholic places of worship started. Secondly, the land where the Mass house was built was owned by the Earl of Bessborough, so he obviously was agreeable to it. He would have a slightly selfish interest too, as he wanted to keep his tenants happy, and on the straight and narrow, and a place to worship would have been very important to many.

The godfather of the modern day parish was Father James Purcell who was the first Catholic priest to base himself wholly in the parish since the Reformation. He arrived in 1748 and was responsible for not just Mooncoin parish but also most of Kilmacow parish. He became the catholic 'Parish Priest of RathKieran'. Fr Purcell rented a house and 40 acres in Middlequarter close to the home - described as a mansion - of the Church of Ireland vicar for the parish who lived in Polerone. Fr Purcell was from Kilkenny City and born in 1707. He moved his brother and parents down to Mooncoin to live with him and work on the farm. His parents died just two years later in 1750, within four months of each other, and were buried in Rathkieran churchyard (of course then still controlled by the Church of Ireland which shows the relationship between the two religions was quite amicable at local level). Fr Purcell got on very well with COI PP Rev Hueuston and his large family. They often visited each others homes. They would have had many things in common, being able to read and right, both would have studied latin etc.

By the late 1700s, there were three Catholics churches/Mass houses in use. It is perhaps not coincidental that the three Catholic divisions in the parish - Mooncoin, Carrigeen and Kilnaspic - did not take any of the names of the older civil/Church of Ireland parishes (such as Tubrid, Rathkieran etc.). Thus, their could be no confusion or mix up between the Church of Ireland and Catholic parishes. There was a Catholic Mass house (later a church) built in Ballytarsney - this was known locally as Curracaleen (probably from the field name it was located in). Then from the early 1800s, after the Penal Laws were relaxed even further, churches were built in the three parishes with an adjoining parish school in each. A new church was built in 1802 in Mooncoin and was located in what we know as the 'old graveyard' on Chapel street (hence where that name came from). This replaced the Ballytarsney church. In general in Mooncoin, there is not much evidence of conflict between the differing churches. Many Catholics attended service (and as stated were buried), in Protestant churches as they had no church of their own until the 1700s. The arrival of a Catholic priest into the parish in the 1700s hastened the demise of Church of Ireland clergy as they now weren't called on to help the Catholic parishioners.

To highlight how ambiguous the situation was in the 1700s, both parish priests Mooncoin/Rathkieran, the Catholic Fr Purcell, and COI Rev Heuston, are both buried in Rathkieran graveyard.

Here are some Extracts from the Ossory records from 1837 which reference the Church of Ireland churches in the area:

(* note; 'Glebe house' is the local Rectors house)

MOONCOIN

"Moncoin", Mount-Coin, or [Mooncoin], a village and extra-parochial

place, locally in the parish of Poleroan, barony of Iverk;

containing 102 houses and 495 inhabitants. In the R. C. divisions this place

is the head of a union or district, comprising the parishes of Rathkyran,

Aglishmartin, Portnescully, Poleroan, Clonmore, Ballytarsna, Tubrid, and part

of Burnchurch, in which union are three chapels.

[From A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (1837)]

Church Records

Civil Parish: RC Parish: Mooncoin

Earliest Records: births. Dec 1797; marriages. Jan 1772.

Polerone

"Polerone", or Poleroan, a parish, in the barony of Iverk, county

of Kilkenny, and on the north-eastern bank of the river Suir;

containing 1245 inhabitants. The living is a vicarage, in the diocese of Ossory,

united by act of council, in 1680, to the vicarages of Potnescully and Illud,

together consituting the union of Poleroan, in the gift of the Corporation

of Waterford, in who the rectory is impropriate. There is a glebe-house [vicar's home] with

a glebe of 4 1/4 acres. About 60 children are educated in a private

school.

RATHKIERAN

"Rathkieran", or Rathkyran, a parish, in the barony of Iverk, county

of Kilkenny; containing 1408 inhabitants, of which number,

120 are in the village. The parish comprises 4197 statute acres, and the village

contains 22 houses. The living is a vicarage, in the diocese of Ossory, and

in the patronage of the Vicars Choral of the cathedral of Kilkenny; the rectory

is appropriate to the dean and chapter. At Moncoin is a school under the superintendence

of the nuns, in which are about 250 girls; and in a private school are about

200 boys; there is also a Sunday school.

AGLISH

"Aglish", or Aglishmartin, a parish, in the barony of Iverk, county

of Kilkenny, on the

river Suir, and on the road from Waterford to Carrick-on-Suir; containing

401 inhabitants, of which number, 142 are in the village. It comprises 2414

statute acres, and is a rectory, in the diocese of Ossory, and in the patronage

of the Crown: the tithes amount to £96.18.5 1/2. There is neither church

nor glebe-house; the glebe consists of 2 1/2 acres.

BALLYTARSNEY

"Ballytarsney", a parish, in the barony of Iverk, county of Kilkenny; the

population is returned with the parish of Poleroan. The parish is situated

on the road from Waterford to Limerick, and is about five British furlongs

in length and breadth, comprising 1116 statute acres. It is a rectory and

vicarage, in the diocese of Ossory, and forms part of the union of Clonmore.

CLONMORE

"Clonmore", a parish, in the barony of Iverk, county of Kilkenny,

and province of Leinster, 2 1/2 miles (S. S. E.) from Piltown, on the mail

coach road from Limerick To wateford. Containing 702 inhabitants. The principal

seats are Silverspring and Cloncunny. The living is a rectory and vicarage,

in the diocese of Ossory, united to those of Ballytarsney, and in the patronage

of the Bishop. The glebe-house [vicars house] was built in 1817: the glebe comprises 11 acres.

The church was erected in 1818 [Graigavine], In the R. C. divisions this parish is in the

union or district of Mooncoin.

PORTNASCULLY

"Portnascully", or Portnescully, a parish, in the barony of Iverk,

county of Kilkenny; containing 1084 inhabitants. It is a vicarage, in the diocese

of Ossory, forming part of the union of Poleroan; the rectory is impropriate

in the corporation of Waterford. contains the chapel of Carrigeen. About

240 boys are educated in two private schools; there is also a Sunday school.

TUBBRID

"Tubbrid", or Tubrid, a parish, in the barony of Iverk, county of

Kilkenny;

containing 213 inhabitants and comprising 980 statute acres, as applotted

under the tithe act. It is a rectory, in the diocese of Ossory, forming part

of the union of Fiddown. In the R. C. divisions it is part of the union or

district of Mooncoin. A day school, in which about 100 children are taught [beside Kilnaspic Church],

is aided by contributions from the parish priest; and a Sunday school is held

in the R.C. chapel.

Historical Geography

Townlands

(1851)

|

Parish

|

Townland

|

Acres

|

Diocese

|

| Tubbrid | Barnacole | 120 | Ossory |

| Tubbrid | Barrabehy | 539 | Ossory |

| Tubbrid | Tubbrid | 344 | Ossory |

As many people with an interest in genealogy would know, the earliest complete census return in Ireland is the 1901 census. This census is freely available on the Irish National Archives website (the Tithe Applotment books which list the heads of most households in Mooncoin cir 1830 are available freely there also -Tithes were a tax on all people for the upkeep of the state Protestant Church at the time - it was later considered an unfair tax, especially as there was an explosion in catholic church buildings in the 1800s).

Mooncoin parish, however, has been staggeringly luckily in relation to information recovered from earlier censuses. Firstly, the background to the completion of censuses in Ireland; censuses were taken every 10 years from 1821 (1821 being the first official census by the British government who ruled Ireland at the time). Many people then ask; so what happened to all the census records from 1821-1891? The 1861 and 1871 censuses were purposely destroyed by the government shortly after all the data had been analysed. The 1881 and 1891 censuses were ‘pulped’ by the British government during World War I because of a paper shortage at the time. The vast majority of the remaining censuses extracts were destroyed during the Irish Civil War in June 1922 when the Four Courts in Dublin was burned. The Irish records office was located in the same complex and over 1000 years of history was burned also at the time.

As stated, Mooncoin parish has been very fortunate (in comparison to most areas of Ireland), in relation to the what survived from the earlier censuses;

1841/1851: The only transcripts in relation to the whole of County Kilkenny to survive from the 1841/51 censuses are the townlands of Aglish and Portnahully (viewable in the national genealogy centre, Kildare St, Dublin 2).

1831: The only transcripts in relation to the whole of County Kilkenny to survive from the 1831 census are the townlands Aglish, Clonmore, Kilmacow, Pol(e)rone, Rathkieran and Tybroughney (viewable in the National Library, Kildare St, Dublin 2).

1821: For the 1821 census, there survives a full complete transcript of the census for the Parish of Mooncoin. Again, Mooncoin is very fortunate, as a man by the name of Edmond Walsh Kelly (who's family came from Glengrant and Licketstown) , who had an interest in genealogy, visited the archives in the Four Courts around 1918 and transcribed the original 1821 census into his notebooks before they were destroyed in 1922 (he was also responsible for the other census transcripts mentioned above). The census transcripts were later copied by his niece Kathleen Kelly (Tramore) in 1976, who made them available for publication. These transcripts are all stored in the National Library of Ireland and are known as the 'Walsh-Kelly notebooks' (GO MS 684). This census was first published in the book 'Mooncoin - 1650-1977'.

As the 1821 census was the first of its kind, the information would have been less detailed than it is today. The transcripts of the 1821 census are available to view below. Just click on the specific townland to open the return. Note: the person listed is son or daughter of the head of the household unless otherwise stated. Houses were usually visited one after the other, so if you can find a family you know, the neighbouring homes would be next on the list etc.

Family Roots / Mooncoin Genealogy

Many people have emigrated from Mooncoin parish over the years. Here is some advice when trying to locate ancestors;

-Gather as much solid information as possible. The townland the person was from is very important. This is especially vital if your ancestor had a common surname like Walsh, Delahunty or Mackey, which are popular in the area. Also, the tradition in Ireland was to the name the first son after the paternal grandfather and the first daughter after the paternal mother. The second son/daughter was then named from the maternal side. So if a grandfather had a large family, many of his grandchildren could have the same name as himself and all in the same parish! This is why dates are very important. It is also, for example, why there has been so many Michael, Patrick, John and Richard Walshs' from Mooncoin over the years!

Also, be careful of spelling changes in names over the years. Many people that emigrated to America could not read or write, so officials on the American side often spelt the name phonetically. This was compounded probably by the accents of the Irish! For example, Henebery, which is still a popular name in the area, has had many variations through the years; Henneberry, Henebery, Henebry and also an American version Hanabery (which was probably corrupted as defined above). The same can be said for the local townlands, they have changed spelling considerably (mostly abbreviated) over the years e.g. Polerone was Polleroan. Kilnaspic was Killinaspick (so try a number of combinations when searching). There is no such thing as a 'correct spelling' as language is fluid and changes through the centuries.

-One of the best, and freely available sources of information is the 1901 and 1911 censuses of Ireland (from the national achieves of Ireland website). Also, on this Mooncoin website, the census of 1821 for the parish is published (above), which we are very fortunate to have surviving.

-Civil records; the vast majority of Births, Deaths and Marriages were recorded in Ireland from 1864 for Catholics and 1844 for peoples of the Church of Ireland faith. These are available free from; www.irishgenealogy.ie.

-Catholic Church records; these are very important as they predate the civil records. In Mooncoin's case, genealogists are very lucky once again, as most marriages and births from 1779 onwards are recorded (Mooncoin was ahead of its time as many parishes did not do this for many years after). These are available from the National Library of Ireland website.

-Other sources include Griffiths Valuation (cir 1850) which is freely available online. This was a land survey but recorded the head of each landowning household in the parish. Likewise, many genealogy websites have records (for a fee) of ship passengers who emigrated from Ireland. These would include the address where the person was travelling from and going to.

The Rev. Carrigan's history of Mooncoin

"The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory" (1905) by the Rev William Carrigan (d 1924), has become the de facto reference when completing any type of research or study about Kilkenny. The books (in four volumes) were the result of fives years work by a local priest William Carrigan who was born in Ballyfoyle Co Kilkenny and have a thorough breakdown of the history of Kilkenny villages.

The books are no longer in print but are available in local libraries. Also, priests ordained in the diocese of Ossory received the books as a gift on their ordination.

Click the link below to read extracts from "The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory" that are specific to Mooncoin;

Mooncoin Extracts from Carrigans Book (volume 4)

A Black and Tan ambush occurred at Sinnott's Cross, Tubrid (at the Piltown end of Clogga) during the Irish war of independence(1919-1921), on the 18th June 1921. At this time Ireland was under the control of the British Empire and many of the people of Ireland rebelled against their control to try and gain Independence. Michael Collins (nationalist icon from Cork), along with Richard Mulcahy, were the main driving forces behind the Irish Independence movement after 1918. Michael Collins was the IRA Director of Intelligence and was actively involved in providing funds and arms to the IRA units around the country. In early 1921 Michael Collins sent a dictate to the IRA Brigade leadership in Kilkenny City ordering them to proceed with ambushes and other activities in County Kilkenny. Much British army resources, including the Black and Tans, were being focused on Cork, Tipperary and Dublin. So Collins needed the Crown Forces to start spreading their resources more widely, so to take the pressure off other areas. In this vicinity, most of the activities during the War of Independence were focused in west Kilkenny (with the 7th Kilkenny Battalion in Callan being the most active). In light of this order, the Mooncoin IRA (9th Battalion) proceeded with an ambush near Sinnott's Cross, Tubrid, Mooncoin, in June 1921.

It would have been easy and less dangerous for these Mooncoin men to do nothing and wait for others to do the 'dirty work'. But these locals felt it was right and the most just thing to do. They had nothing to gain in the short term, but perhaps had a lot to lose. These losses could have included their farms, their jobs, their freedom or their own lives. This was because marshall law was running in Kilkenny at this time in 1921, which meant they could be executed without trial if captured at an ambush. In fairness to these Mooncoin men, they were quite ordinary people. They did not want war or killing. But it was because of their sacrifice that we now live in a thriving Republic with its own parliament, culture and identity.

Now just to set the national scene as it was in June 1921 when the Sinnott's Cross ambush occurred. The country was in turmoil for nearly two years at this stage due to the 'Tan War' as it was called, or what we now call the Irish War of Independence. People in Mooncoin would have been glued to the daily newspapers. And in general, the tide of sympathy was turning towards the Irish revolutionaries even from people that would previous have had moderate views. If we flash back just eight months before the Sinnott's Cross ambush, the world was following the demise of Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwinney, on hunger strike in England. His subsequent death was an international sensation reaching the front pages in the UK and America. Then just a few weeks later (7 months before Sinnott's Cross), the Croke Park Massacre occurred. This was a response to the Michael Collins's led assassination of British detectives. Then to make matters worse, the Black and Tans burnt down Cork city centre, just 6 months before Sinnott's Cross. As a quick summary, the Black and Tans were a mercenary force setup by the British. They basically had a licence to 'fight fire with fire' with little or no repercussions from their superiors. History would show that this backfired badly on the British, as many people that were affected by the Black and Tans were law abiding, innocent people. The Black and Tans enemy was basically all Irish people which is why they burned down creameries and farmhouses. This ironically was beneficial to Michael Collins and the leaders as people really started backing them now more than ever. Thus, Mooncoin could not have been immune to the raised tensions sweeping the country in the preceding months.

To provoke the Black and Tans to come to Clogga the local IRA men broke into and stole objects from the local landlord who lived near the mill. The Landlord reported this and this caused the Black and Tans to come to Clogga. Fiddown bridge was also set alight five days earlier - although little damage was done - to increase Black and Tan patrols. Also, the previous year (1920), Piltown Courthouse was burnt down. Pat 'the fox' Walsh (Richtén Walsh's later Swithin Walshs) of Clogga was the leader that day.

At a turn on the road, very near Sinnott's Cross, the local IRA members waited for 12 hours and then ambushed the Black and Tans as they cycled past, killing one - Albert Bradford - and injuring another. The Black and Tans did not know who committed the attack and vowed to "burn every house in Clogga to the ground". But thanks to the local miller, this did not happen. The miller at the time, Mennell, was from England and told the Black and Tans that it was an outside unit of the IRA. The Black and Tans trusted him and so did not harm anyone in Clogga.

It is important to highlight that the men - and supporting women and scouts - that took part that day were mostly local. They came from different walks of life, big and small farmers,labourers, shop keepers etc. They put their own lives and their families livelihoods at risk to fight for a cause in which they truly believed in. There was no financial or other rewards, but the sacrifices could have been huge. They obviously believed strongly enough in the cause to take part.

|

Ambush Turn. Site of the purposed Sinnotts Cross Monument (2004)and work to date (2008) |

Sinnotts Cross |

Pat'the fox' and James Walsh who took part in the Ambush |

|||

| The sculptor of the monument, Ruairí Carroll, adjudicates on the final placement of his piece of art on the plinth (Feb 2009). |

Sinnotts Cross Monument 2009 |

||||

At the end of 2003 it was decided to erect a monument at the site of the ambush for all men and women who fought for the freedom of Ireland. The final monument, in Kilkenny sourced limestone, depicts hands (perhaps depicting the people of Ireland/Mooncoin) holding up the country. For the full story of the ambush Click here.

Here is an account

from Martin Murphy of Grange who was involved in the ambush:

"The Clogga ambush occurred shortly after the failed attack on the

Mullinavat Police Barracks. We gathered near Sinnott's Cross about 3pm. We

got a signal the Tans were coming. We rushed into our positions. The Tans

came along the road cycling. We fired at the Tans mostly with shotguns. One

of them fell dead. We captured his rifle. Another Tan was wounded but he managed

to get away. Ted Moore was one of those in charge. We all got away. This ambush

happened in June 1921."

Thesis on War of Independence in Kilkenny

Watt Murphy, the Carrigeen Affray & The Rose of Mooncoin

Mooncoin has been made famous by a love song called the "Rose of Mooncoin". It was written by Watt Murphy in around 1850. It has now been adopted as the Kilkenny county anthem (thanks to Paddy Grace, Dicksboro - former county chairman) and it is sung to represent the Kilkenny hurling team when victorious.

Watt's father came to Mooncoin and set up a school in Ballyfoy, near Carrigeen in the early 1780s where he was principal. Watt was their only child, born on 21st or 22nd April 1790, and the family lived in Rathkieran, then Ballyfoy and later Watt lived in Polerone.

|

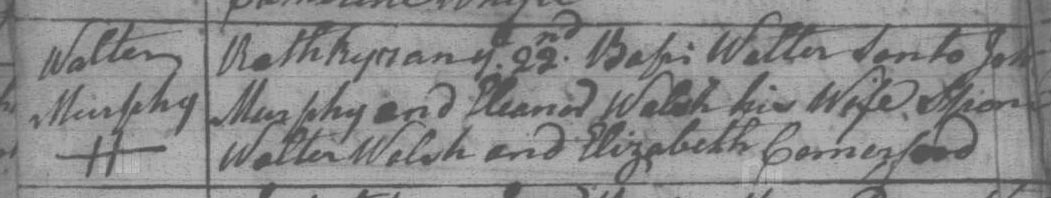

Watt Murphy's baptism registration in the Mooncoin Parish register. "Walter Murphy, Rathkyran ['inst'/current month - April 1790] 22nd, Bapi Walter son to [John/Patk?] Murphy and Eleanor Walsh his wife. Sponsor Walter Walsh and Elizabeth Comerford" |

Watt was educated at his father's school and eventually started teaching there himself at age of just 16 in 1806. Then, in the late 1820s, he established his own school in Chapel Street, Mooncoin, having been evicted from Ballyfoy (which would have been in the townland of Corluddy). Watt's new school was located roughly where the 'Mews' houses on Chapel Street are currently, and people who could afford it would send their children there. Watt was a brilliant teacher by all accounts, having picked up so much skills and knowledge from his father from a young age.

The Carrigeen Affray - October 1832

By the 1830s, people were beginning to push back strongly against paying tithes. These were a 10% tax on your yearly farm income to help the upkeep of the 'established church' i.e. Church of Ireland churches. Catholic Emancipation had just happened in 1829, and Catholic churches were in situ in Mooncoin parish for decades now, so the need to still pay these tithes were making some very angry. During the 1700s and earlier, when there was no Catholic churches, an argument could be made for them, as Catholics were usually laid to rest in Protestant owned graveyards while the local minister would often offer spiritual assistant to Catholics in need. But by 1832, the CAtholics had equal rights and were using their majority voices. Tensions were already at high level in this part of the country. The 'Tithe War' had been kicked off two years earlier by a priest in Graignamanagh. Ten months before the Carrigeen Affray, 17 people were killed, the majority police constables, in nearby Carrickshock (Hugginstown). So when the 1832 tithes were due for collection in October, things were on a knife edge, and events in the parish would make the national headlines.

Police Constables on horseback - who were quasi military and a precursor to the RIC, sometimes called Peelers - came into the parish from their base in Kilmacow on Wednesday 3 October 1832. Their job was to erect posters in all the civil parishes that made up Mooncoin, stating that the Tithes were now due by the locals (it was their '14 day notice'). They had only got to Polerone when a large crowd were flowing them, jeering them, and some throwing stones. They were of course protesting against the tithes and believed the Constables were doing dirty work against the average person. Constable Webb ordered his me to flee all though the people gave chase. Constable Webb took refuge in the house of Michael O Connell in Rathkieran and the local Catholic parish priest, Fr Carroll, was called for. He calmed the crowd and walked back to Kilmacow with the police constables to guarantee their safety.

Although he did not want to see violence, the priest wrote to the authorities afterwards saying the polices actions were highly provocative in an extremely charged environment. the events of the day were seen as victory for the ordinary people in Mooncoin. The police force in Kilmacow, which had Mooncoin in its area, were extremely embarrassed to have 'lost' against a 'mob'. The police had also expended 20-30 rounds, to try and scare off the crowd, which would be seen as a wasting good ammo by their superiors. So the following Tuesday, they came back to parish to finish the job of erecting the notices. This time they got help from the military from Waterford and Carrick. The three groups spilt up and went at their job from different directions in the parish. In all there was around 70 men involved in the operation.

The Kilmacow Constables this time were led by Captain Burke. As they erected notices in Mountneill, Portnahully and Moonveen, the crowd following jeering them started growing larger and larger. The majority were said to be women and children. Some were saying 'remember Carrickshock'. As they got near Carrigeen village at around 1.00pm, the church bell was rung and more people were alerted. Nearly 50 children came out of the school house too beside the church to join the crowd which was probably now over 150 people following the police. Feeling he was becoming surrounded, Captain Burke shouted; 'disperse, disperse'! He then ordered his flank to come around and open fire on the crowd. This time, they were not going to waste their ammunition.

Catherine Foley, who was aged 17 and from Luffany, died instantly, the bullet having passed through her spine. Joseph Sinnott, who was 19 years old, died the following morning, the bullet having passed through his body from the back and through the intestine. He died in Richard Quinn's house - the thatch cottage still in the village we believe - who was the Carrigeen school principal at the time and who had aided Sinnott after the attack.

Another young man, James Delahunty, was very lucky. He was turning to run as fire was opened and the bullet passed through his cheek, cut the top of his tongue off, but went out the other cheek. The other soldiers only dashed to Carrigeen once they heard the shooting. One party had just put up the notice at Ballygorey pump when they heard it. The crowds fled for their lives once the firing started so the soldiers and constabulary had no problems getting home.

The inquests into the deaths of Joseph and Catherine were held in Comerford's pub on Main Street, Mooncoin the following day. The inquest heard the testimony of Joseph Sinnott who gave an account of what happened to doctor before he died. Sinnott said; 'I pelted no stones at the police, I had no stick, pike, fire arms or stone when the police fired; no person pelted a stone in my view; I was running away when I was shot in the back - I did not advise any person to pelt or not to pelt; when I was stretched near the ditch, the police caught me by the breast, opened my eyes and said "the rascal is not dead yet"'. Joseph Sinnott was from Ballybrassil and the oldest in a family of five, his father had passed away when he was a boy. Sinnott was buried in Mooncoin old graveyard, near Comerford's carpark direction.

The inquest jury, made up of 12 local 'respectable farmers' found Captain Burke guilty on both counts of willful murder. Burke surrendered himself in Kilkenny City to the magistrate, but it was also for his own protection. Within a week, Burke was released and the inquest findings rejected by the magistrate on a technicality, saying the charges were too vague and not enough detail was given for the seriousness of the charges. The following March, at a subsequent trial, the charges were again thrown out. Although people expected as much, there was still a lot of anger. They could not have been surprised however. One of Captain Burkes superiors afterwards wrote: 'Captain Burke's actions has restored to the Constabulary of the country, that character which they lost at the unfortunate Carrickshock affair'. The Carrickshock and Carrigeen flash points were part of the reason the much hated Constabulary/Peelers were disbanded in 1836 and replaced by the RIC.

The local Church of Ireland minister in Mooncoin, Reverend Newport, who called on the authorities to enforce the tithe collection in the parish, quickly requested a transfer from his home in Polerone, in fear of his safety. Watt was deeply affected by this which became known as the 'Carrigeen Affray'. He wrote a poem disgracing the authorities. He was severely reprimanded by the authorities for his poetry, who also stopped his income as school principal. This gained him the nick-name "the Rebel poet". He was reinstated though sometime later. He also wrote a famous prose about the 'Battle of Carrickshock' which happened a year before the Carrigeen incident, in 1831. He heard a firsthand account of Carrickshock from one of the participants who escaped to Mooncoin after the fight and eventually got across the River Suir.

Watt's school had became a parochial, not a private, school in 1833, so his wages were paid directly by he church. In 1839 the three parochial schools in Mooncoin, namely Chapel Street (Watt's School), Carrigeen and Kilnaspic became state schools. This guaranteed Watt an income of £10 per year, while the building were still owned by the church (the covent school was run by the nuns independently but was already state sponsored at this stage). So, the only private schools left were on the New Road in Mooncoin and one in Cussana (the New Road Boy's School came under state control in 1855 with 169 boys on the roll with an average attendance of 88).

The state taking over the schools were positive in one way for the Church as the state now paid the wages of the teachers. Watt also got a pay rise with his £10 per year and also a second teacher, Richard Walsh. He needed him, as by 1844 there were 170 pupils on the roll in the school with an average attendance of 140 pupils (70 each!). There would be less pupils attending on wet days, or during harvest etc, or sometimes family member used to take turns on who would go to school and who were required to stay home. The state takeover was a big disadvantage in another way, as there were inspections by the state authorities quite frequently to check the calibre of the teachers; but mostly that the British approved curriculum was being taught. Watt received two official warnings from the authorities via the local parish priest for his attacks on the government and the politics of the time. The state schools were meant to portray a positive image of the monarchy and empire. Eventually the parish priest was required to sack Watt from the school which occurred in 1846. It must have been difficult for him as he had originally founded the school off his own bat. An inspection report from December 1946 was quite honest about the morale dropping after his absence, stating that 'a great cloud hangs over the school since the teacher [Watt] was dismissed'. Over the next few years, all the parish schools were struck off the state register at one stage or other following disagreements with the inspector.

However, maybe Watt's sacking was a blessing in disguise. The local rector had just become his new neighbour in Polerone; the Rector's house (Glebe) was located beside Polerone Church. The new Reverend, James Wills and his family of three sons and one daughter (his oldest child) arrived in Polerone in 1846. They had lived in Rathkieran before this and the Reverend took over the titles of Vicar of Polerone and Curate of Rathkieran. All the children were highly educated just like their father had been.

Watt became infatuated with the Rector's daughter, Elizabeth, also known as Molly. They were both intellectual and would walk the banks of the Suir along Polerone reciting and writing poetry. It is said that Watt became a permanent fixture at the front porch/terrace at 'Suirville House', the rector's house in Polerone, which faced onto the River Suir. It is said they loved watching the comings and goings on Polerone Quay, looking at the fisherman and the boats that commuted up and down the River Suir from Carrick to Waterford with deliveries everyday. One of Watt's famous poems was titled; 'Polerone Graveyard'. The Rector was not pleased to hear that both Elizabeth and Watt were in love, especially given the age difference (Watt was in his 50s and Molly was just 20). He had initially thought it was just a student/teacher interest. He also didn't approve of Watt's rebel tendencies. So he sent his daughter to England in 1848 and the rest of his family moved to Kilmacow after he requested a transfer. Watt was heartbroken as a result of Elizabeth leaving Mooncoin. So as he walked the banks of the Suir, now on his own, he composed the famous Rose of Mooncoin in her memory. He died just 10 years afterwards and is buried in Rathkieran cemetery.

Click

here to listen to the rose of Mooncoin

Click

here to listen to the rose of Mooncoin

|

The Rose of Mooncoin How

sweet 'tis to roam by the sunny Suir stream Oh

Molly, dear Molly, has the time come at last She

has sailed far away o'er the dark rolling foam Then

here's to the Suir with its valley so fair |

There has been different schools in Mooncoin over the years. When the landlords first took control of the lands they set up schools where a select few were given the privilege of attending. The landlord paid for these schools. Private schools were set up in the late 1700s, some run by the Catholic church, others fully private. At one stage there was Watt Murphy's school in Chapel Street, a parochial school on the New Road and a convent school for girls on the main street (not including the parochial schools in Carrigeen and Kilnaspic, and a private school in Cussana). Later a boys school was opened for Carrigeen parish in Clasharoe, with the girls located in the school beside the church.

During the 18th century, only the better off could afford to send their children to school. Families that could afford to pay, paid for their children's education, but families that couldn't afford to send their children to school, were sometimes paid for by the parish priest if the child showed promise. As the Catholics gained more rights (after 1782 and subsequently Catholic Emancipation in 1829), the Catholic church set up schools or took over schools around the parish, though from 1833 some of these schools began to be financed by the state (which saved the Catholic diocese a lot of money). Watt Murphy's school on Chapel Street then came under the patronage of the church along with schools in Kilnaspic (just beside the present church where the ramp is located today) and in Carrigeen village. In 1830, the parish priest invited the Presentation sisters in Kilkenny City to set up a school for girls in the village of Mooncoin (his philosophy was 'educate a boy and you educate the individual, educate the girl and you educate a family'). The convent was then located on Main Street, Mooncoin, in the house that's roughly opposite the car park of Centra supermarket currently, often called 'Doctor Dwan's House' (Main st, Mooncoin, was actually called Convent Street at the time). The nuns though built a school house on the Polerone road, near where the church is at the present day. The syllabus in all schools was concentrated around the three R's. Religion made up a big part of the daily study. So from 1832, nearly all children up the age of 10 got a chance to at least read and write. In this regard, Mooncoin was lucky, as many parts of Kilkenny and Ireland did not have this opportunity until many years later. This is highlighted in the 1901 census, as the vast majority of people in Mooncoin, of all ages, could read and write.

In the late 1800s many additional school buildings opened around the parish. There was a separate boys school built in Mooncoin on Main St, near the present day Centra (Murphy accounting location), which replaced the school on Chapel st. In addition, there was the Presentation nuns run girl school. In Carrigeen, there were separate boys and girls school in the Clasharoe and beside the church. Clogga national school and Clonmore national school were open on the same day in September 1888 (and closed on the same day in 1969). There had been two schools in Clonmore during the century previously, established by the local protestant minister based in Clonmore House. Clogga school replaced the old Kilnaspic school which had closed down some years before.

A technical school was opened in Mooncoin in 1935 where the present day furniture store is located. It then became a Vocational school. A new building was opened in 1993 and was renamed Cóláiste Cóis Súire in 2001.

Seamus Doran:

It should also be noted that Mooncoin is the birth place of the national organisation Fóroige (first meeting held in Mooncoin technical school in 1952) and had the first branch of Macra na Feirme. These organisations, which are spread throughout Ireland now, were inspired by a teacher named Seamus Doran, a Wexford native, who taught in the technical school from the 1940s and was principal up until the 1980s (died in 2007). He was honoured in the school by President

Mary McAleese to celebrate 50 years of Foroige in 2002. His Macra na Feirme group was also one of the main driving forces behind the establishment of the farmers union, the IFA, in the 1950s.

In late 1600s the penal laws where introduced by the English government who controlled Ireland at the time (after protestant King William of Orange's victory over his catholic uncle, King James II). They prohibited the practice of the Catholic religion which most of the Irish people had as their faith at the time. The main purpose was to wipe out the Catholic faith within a generation or two. This policy actually worked well in England, at present just 10% of the population is Catholic.

The people now had to practice their Catholic faith in secrecy. The Mass bush is where the people met to celebrate Mass with a priest (on his irregular visits to the area). With the penal laws, Catholics were also prohibited from buying land and from entering the forces or the law. Catholics could no longer run for elected office or own property (such as horses) valued at more than 5 pounds. In the early years of the 18th century the ruling protestants in Ireland passed these laws designed to strip the 'disloyal' Catholic population of remaining land, positions of influence, and civil rights.

A well known Mass bush in the parish of Mooncoin is located at the top of Tubrid beside Knockanure (there were a few Mass bushes at different times). There is a good view around the valley, this was to ensure that the people could keep a look out. It is possible to see four counties (Kilkenny, Waterford, Tipperary & Wexford) from that position. There was also a Mass bush at the crossroads in Ardera and Mooncoin village and a 'priests trench' on the road between Dournane and Polerone where a visiting catholic priest could say Mass.

|

|

Mass Bush

|