|

When I take that trip to Kildorrery to visit the little church at Farahy, on the lands at Bowen's Court, I feel I'm stepping back in time. Perhaps it is the scenery, unchanged over many decades, the winding tree-shaded roads, the old villages steeped in age, that gives the same emotional response that the writer Elizabeth Bowen felt when she lived and travelled in this place. When I take that trip to Kildorrery to visit the little church at Farahy, on the lands at Bowen's Court, I feel I'm stepping back in time. Perhaps it is the scenery, unchanged over many decades, the winding tree-shaded roads, the old villages steeped in age, that gives the same emotional response that the writer Elizabeth Bowen felt when she lived and travelled in this place.

I take the road from Fermoy, past the cromlech, or Hag's Bed at Labbically, through Glanworth, and on to Kildorrery town that is famed in song and story. On the way I pass through the old village of Rockmills, which looks as if it had once been a very important place, not quiet deserted, but with a new touch of colour of late as some houses have been decorated. Now I swing west along the road that leads to Kanturk, Buttevant and New Market. We are now nearing Bowenscourt and travelling along a road that the great writer must have known in happy familiarity.

Downhill I drive and cross a little bridge and soon I am at the carriage-turning entrance to that famous house which no longer exists.

Near the entrance, and also near the small bridge was a shop and here Elizabeth was able to purchase the occasional needs of the big house that perhaps she had not bought in Fermoy or Mitchelstown.

It would have been along this road, too, that she would have travelled when she made her trips to England during the war years, when she spent a great deal of time in London.

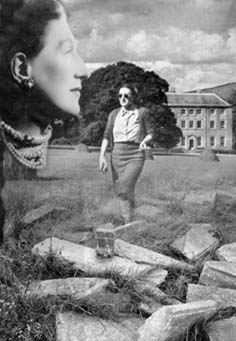

All that now remains to remind us of Bowen's Court are the entrance gates and the little church at Farahy where both Elizabeth Bowen and her husband Alan Cameron are buried just across from the church door.

She had married Alan Cameron after a short courtship in London in 1923 and they were a happy couple. He fought in the war in France and then went on to become Director of Education in Northhamptonshire and, in time, went to work with the B.B.C. on educational programmes.

It is easy to imagine life in the big house when Elizabeth spent her younger years there. The parties, hunting meets, the musical evenings, the social scene. Years when the big house was a symbol of all that was proud and powerful in the countryside.

Then came the changing years, the years when the fight for freedom boiled over into an open struggle. It frightened and impinged on the lives of the people in the great houses, even if they tried to persuade themselves that nothing could change their lives.

Elizabeth was conscious of this and I went back to my copy of her novel, 'The Last September', to read again the passage which evokes the chilling feeling when strange men, in strange uniforms, moved over your property with casual ease.

We experience the following scene through the eyes of her heroine, Lois, who walks out into the dark avenue of the big house.

"High above a bird shrieked and stumbled down through dark, tearing the leaves. Silence healed, but kept a scar of horror. The

shuttered-in drawing room, the family sealed in lamplight, secure and bright like flowers in a paperweight were desirable, worth much of this to regain. Fear curled back from the carpet border... Now on the path; grey patches worse than the dark; they slipped up her dress knee-high."

Bowen goes on to describe the moment when fear returns. Lois feels she is going to see a ghost. Then she hears steps:

- Hard on the smooth earth; branches slipping against a trench-coat. The trench-coat rustled across the path ahead, to the swing of a steady walker. She stood by the holly immovable, blotted out in her black, and there passed within reach of her hand, with the rise and fall of a stride, a resolute profile, powerful as a thought. In gratitude for its fleshiness, she felt prompted to make some contact; not to be known seemed like a doom; extinction.

'It's a fine night,' she would have liked to observe; or, to engage his sympathies: 'Up Dublin,' or even - since it was in her uncle's demense she was straining under a holly - boldly, 'What do you want?' -

Of course she does nothing to give away her presence, feeling that it - 'Must be because of Ireland he is in such a hurry.' -

One can imagine the feelings of the Anglo-Irish at the time when the new young men of power walked across their lands without so much as a "Beg your pardon."

The residents of the houses were only too aware of the fight for freedom and at dinner in the big house there are talks of an attack on a police barracks and the killing of two policemen. There are also talks of young girls having their hair cut off when found to be consorting with British soldiers. It was the same punisment they used in France after the liberation, but then it was to girls charged with meeting German soldiers.

All the old fears of that period have been dissipated with the passing years, and now the local people, from both denominations, gather together on a special afternoon in September to remember a fine writer, who remembered how it was.

Elizabeth loved two countries in her life, England and Ireland, and that comes through in her writing as vividly as if it had been written in the recent past. It is good to know that Bowenscourt was never to know the fate of being burned as a reprisal. It was to live on in the emerging Ireland and was only to meet its demise for economic necessity. There is nothing left of the big house now, but Elizabeth Bowen will always be remembered in her stylish and fine writing and also at the little church at Farahy on the September Sunday.

|

|