3rd edition (revised)

Published by

The

Limerick Soviet Commemoration

Committee

2003

Preface

The Nature of the Irish National

Struggle

One of the more disagreeable features of

the struggle between Irish historical ‘traditionalist and ‘revisionists’

is not their clashes but their de- facto readiness to agree on major issues

without investigation. The traditionalists do have the excuse that they

drafted the line on these issues in the first place, the revisionists

pretend that they question everything.

One such matter of implicit agreement is

the socio-politica1 nature of the revolutionary struggle after 1916, the

traditionalists are happy with the historic perspective of a ‘pure’

nationalist political-military military campaign with no social or

economic aspects. The revisionists are happy to go along with this. The

first school fears lest too careful research provides ammunition to shake

the status quo. Its opponents, or, at least, too many of them, want to

change the status quo only in the political sense and are happy to accept

their opponents’ terms of reference as producing the ammunition they need

in their task of defaming the national struggle for its alleged lack of

social content.

In this matter, both sides are wrong.

The atmosphere in Nationalist 1re1and between 1916 and 1923, and in

Unionist Ireland to 1920, differed from the periods before and afterwards

more than they differed from each other. Partly because of organisational

and political weaknesses in the revolutionary camp itself; this potential

was either strangled at birth or just neutralized by its enemies. It had

been there, however, and it had enough reality to be part of the overall

picture of the years of the national struggle.

For example this was the period when

Ireland led Britain and, indeed, the world outside Russia, on women’s

political rights. This cannot be separated from the rise of Shin Féin. The

only two women running in Ireland in the general election of l918 were

candidates of that party. Had its electoral triumph been much less than it

was, it is likely that Constance Markievicz would not been these

islands‘ first woman MP and that she would not have been the world’s second

woman government minister. Later, with the limited independence given by

given by the Treaty. Women under thirty got the vote on equal terms with

men six years before their sisters elsewhere on these islands.

Such advances were paralleled by the

fact that clerical influence was unusually low. At the time of the l9l7

Sinn Féin unity convention a Catholic priest objected that he was not

seated by right of his cloth alone, as he was at similar Home Ruler

assemblies. Though the Dail cabinet came down at last against democratic,

rather than clerical control of education, it did so after a struggle that

would not be seen again for more than seventy years. It is not really

surprising, then, that the majority of the Catholic bishops remained

hostile to the first Dails and their Republic even after the leaders of

the Home Rule party had accepted the fact that events had overtaken their

programme.

Finally, there was the fact of

internationalism. Republican propagandists translated nationalist works of

other lands. Until 1920 the Irish Theatre struggled to bring to Dublin the

best of foreign drama. None of this meant that Sinn Féin headed a

socialist movement. It did mean that it headed a revolutionary democratic

mass movement. Such

bodies have to face the fact at last

that bourgeois society cannot support too much democracy and that they

must either advance further than the leaders of that society would like in

the direction of Socialism or accept that their programmes be diluted.

The potential approached Socialism into

be sympathetic to Irish national aspirations and the struggle to achieve

them, it was to keep them at arms length, and mobilise only against

specific anti democratic actions on the part of the British occupier. An

attempt by Connolly’s friend, William O’Brien to maintain a Labour

presence within the broad revolutionary front that would become a single

Sinn Féin party without that presence was undermined by the opposition of

his labour allies.

They were not altogether to blame. The

organisation of their movement united as a single entity the industrial

and political movements, so as to make labour politics simply a function

of the Irish Trade Union Congress. The independent Socialist Party of

Ireland remained little more than an infrequently productive publishing

house. This constituted an empirical form of syndicalism: the idea that

one big union was all that was needed to emancipate the working class. It

had been expected to aid recruitment on a clear class basis. In reality,

it made political division a major hazard to the unions as well as the

party that they constituted, and made unity a premium to be achieved, if

necessary through a strategy based on the lowest common denominator.

In a

land where workers were divided politically, like everyone else, between

Unionists, Constitutional Nationalists and Republicans, this meant a

necessary fudge on the national question. Until 1920, this seemed to work.

Membership of the 1.T.U.C.’s affiliates, trades unions and trades

councils, rose from 130,000 at the end of 1916 to 320,000 in August 1920.

The bastion of syndicalism, the I.T.G.W.U., made up the largest part of

this, growing from 5,000 to 120,000 in the same period This growth did not

quite parallel that of the reviving Republican movement after 1916. What

became the new Sinn Féin expanded steadily although 1917, as did the

Volunteers; both appealed beyond the working class to tenant farmers and

small businessmen who made up the broad social front termed

unscientifically ‘the men of no property’. Labour advanced more slowly

until the October revolution in Russia showed it what workers could do and

inspired the Irish along with others.

The national struggle could still affect

Irish Labour positively as was shown the following April. The British

government move to conscript Ireland was met by petitions, pulpit

denunciations and by the constitutional nationalist MP’s taking the Sinn

Féin line of abstention from Westminster. Labour organized the first

political general strike in these islands: the first successful political

general strike in western Europe. Admittedly with aid from the Irish

Volunteers in some non- unionised areas, the stoppage was nearly 100 per

cent successful outside the Unionist north, and it might have been

successful there, had the Belfast Trades Council been able to protect a

previous anti-conscription meeting against loyalist interference. As a

result, 1918 saw Labour and the I.T.G.W.U. breakthrough in areas where

they had been unknown.

lf the 1918 general strike had shown the

possibilities for Labour in advancing the national struggle, the end of

the year gave it a warning against being too detached from it.

Self-determination was bound to become the central feature of the December

general election campaign in Ireland. Labour found too late that it had

allowed Sinn Féin to identity the cause with its strategy of principled

abstention from Westminster. Labour could either oppose Sinn Féin, with

the almost certain prospect of losing, or it could run in tandem with it,

alienate many constitutional nationalist workers and accept paramouncy of

the projected Dai] Eireann over a trade union congress that saw itself as

the prospective, syndicalist ‘Parliament of Labour? Except in four

Unionist constituencies in Belfast, the Labour candidates withdrew. Yet,

as the anti-conscription strike had shown, and as was borne out by

Volunteers and other Sinn Féin supporters joining local general strikes

for better conditions, the Irish working class linked nationalism and

syndicalism ‘in its revolutionary consciousness’, as Leon Trotsky had put

it. It was inevitable that this combination would be expressed more than

would be welcome to the Labour or Republican leaderships.

The Anglo-Irish War, Irish Labour and

Limerick

On 2lst January, 1919, Dail Eireann held

its opening session and the Irish Volunteers drew their first mortal blood

since 1916 at Soloheadbeg, Co.

Tipperary. These facts have set the seal for subsequent historians of the Hist

months of the year. Yet such an emphasis is the product of subsequent

events rather than of judgment of contemporary news. The first Dail

session and Soloheadbeg were, in their time, isolated incidents in a

period that was more notable for industrial unrest. The

Belfast engineering strike

began within days of those two nationalist events and, before the end of

the month, Peadar O’Donnell was leading the Soviet occupation of Monaghan

Asylum. These were just the immediate outstanding stoppages.

That such facts have been downgraded has

a material justification. The existence of the Dail provided a long term

institutional focus for the national struggle that the social ones could

not match, either in the lTGWU or in the Irish Labour Party and Trade

Union Congress. The continuing refusal of these bodies to seek to seize

from the Dail the consistent lead in the Anglo-Irish War enabled the

latter to dominate what labour had allowed to become the initial struggle

against British imperialism. In this position, it won many from the

economic struggle as the national struggle that it led had superseded the

economic issues in intensity by 1920. On the other hand, the Labour

leaders’ justification for their inaction – the need to maintain a single

trade union movement and Labour Party would betray itself in the end when

James Larkin split both.

Although the Irish Labour leadership did not try to take the lead in the

independence struggle, it did act, on several occasions, to advance it by

means - the strike weapon - that it alone could command. On four occasions

from April 1919 to December 1920, the strike was used to assert democratic

rights against lreland’s imperial occupiers. (Another general strike, the

Mayday holiday, was an international initiative). Three of these were

called because of spontaneous rank and tile action rather than the

inspiration of Labour’s National Executive. The remaining one occurred as

the result of rank and tile demand. Two of them (as well as the Mayday

holiday) strengthened rather than weakened Irish Labour as a whole.

Industrial struggles, the proportion of organized Irish workers on strike

in 1919 (70,800 out of 229,786) was lower than that of organised workers

in industrialised Britain (2,901,000 out of 7,926,000); the difference was

more than filled by the political strike figures, which created, in turn,

an industrial atmosphere in which economic strikes were less necessary.

The two exceptions failed, ultimately, due to specific problems. The Motor

Permits Strike of the winter of 1919- 20 was handicapped by inter-union

squabbling. The Munitions of War Strike of 1920 came at a time when the

Labour leadership’s lack of perspective on the national question left it

unable to oppose the Black and Tans; significantly, this political strike

was the last effective one in the Anglo-Irish War.

The remaining example of rank and file

working class action to oppose imperialism is the subject of this

pamphlet. Like the other two examples of such initiatives, it was

handicapped by Labour’s national leadership. Yet, partly because of its

regional character, this handicap did not have as debilitating an effect

on the general Labour struggles of the time as it was to have in the

context of the Motor Permits and Munitions of War strikes.

The Limerick General Strike of April

1919 was, in its way, a classic example of the dialectical synthesis - the

mutual interaction - of the Labour movement’s methods of struggle with the

cause of Irish self-determination. It was not accidental that it should be

a spontaneous initiative of the workers’ syndicalism.

As long ago as 1899, Limerick had elected a local Labour Party, under the Republican, John Daly, to

a majority on its corporation, though disillusion with what had become

another constitutional nationalist iiont had contributed to the

achievement being eclipsed by the notorious anti-Jewish pogrom of 1904. In

1916, Limerick’s Bishop Edward O’Dwyer had been, greatly to everyone’s surprise, the

member of the Catholic hierarchy who had condemned the British executions

of the Easter Rising leaders. In January 1918, its Mayor, Stephen Quin,

had accepted a British Knighthood causing him to be replaced within a

month by a Sinn Féin mayor, Alphonsus O’Mara of the bacon-curing firm,

Dormelly’s. O’Mara was re-elected the next year. This was at a time when

the municipal councils of Ireland were still those elected in the years up

to 1915 and were dominated by councillors who had been supporters in one

way or another of constitutional nationalism. Meanwhile at the general

election of December 1918, Michael Collivet was returned unopposed for Sinn

Féin.

This nationalism had to affect the

city’s United Trades and Labour Council. At the same time, that body was

affected by the working-class’s other contemporary revolutionary current:

syndicalism. This had been slow to appear. Unlike other major Irish

cities, Limerick got no I.T.G.W.U. branch until July 1917. Even then, half the trade

council’s affiliated membership was in non-syndicalist British based

unions. Yet Syndicaist militancy affected all. The council chairman, Sean

Cronin of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters had been very critical of

the influence of ‘Dublin Socialists’ in his movement. By April 1918, he

was hailing the general strike as evidence that his class ‘really ruled

Ireland’.

This had a narrower side. In November

1918, the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress amended its

constitution to allow for some form of political intervention on its side

by individuals outside the unions. The Trades Council of Limerick, along

with those of Cork and Waterford, led the opposition to this breach of

syndicalist principle. This militancy was increased by the fact that the

expansion of the l.T.G.W.U. caused a clash between the Condensed Milk

Company of Ireland and the 600 employees at its plant at Lansdowne. The

workers in all the concerns managed by the Cleeve family combine that ran

the

Condensed Milk Company sent delegates in

April 1919 to form a Munster Council of Action which threatened strike

action for better conditions in the Condensed Milk Company’s factories.

The Company retaliated with a policy of ‘divide and rule’. First of all,

it awarded a 48 hour week at a wage of 11l/4d

per hour (45/ - per week) to its 600 workers at Lansdowne (where it had

its headquarters). At the same time, it sacked the factory’s l.T.G.W.U.

shop steward.

While this proceeded, events were

occurring which led to the clash which would show how the traditions of

nationalism and syndicalism affected the Limerick United Trades Union and

Labour Council’s response to a concrete instance of military repression.

The Limerick Soviet Begins

On Sunday, 6th April 1919, the Co.

Limerick Volunteers went into action. Their mission was to rescue one of

their number, Robert J. (Bertie) Byrne. Byrne was a prominent trade

unionist, a member of the trades council, who had lost his job as a

telegraph operator for his part in organising his colleagues in his union

and (officially) for attending John Daly’s funeral without leave. On 2lst

January 1919, he was victimized thither, this time for his Republican

views. A British Army court martial found him guilty of possessing a

pistol. On 1st. February 35 unions affiliated to the Limerick United

Trades and Labour Council passed a motion of protest against the treatment

of the political prisoners and the inactivity of the visiting justices and

of the medical officer. The motion called on the local deputies and

councillors to ensure the prisoners political status.

None of this had any result. On 3rd

February, Byrne was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment with hard labour.

As the senior officer of the Volunteers imprisoned there he began a

campaign for political status. At last, the prisoners wrecked their cells

and destroyed the fittings. In retaliation, the warders beat them, removed

their boots and clothing and handcuffed their leaders day and night, on a

bread and water diet, in solitary confinement. The prisoners went on

hunger strike. Byrne’s own condition became such that, on 12th

March, he was transferred, under police guard, to Limerick

Workhouse Hospital (now St.

Camillus). It was here, at 6 pm., on 6th April, that his volunteer

comrades tried to rescue him. They failed. A constable T was shot dead, a

second was wounded mortally, and Byrne himself was taken away by the

rescue party, but he had been injured fatally in the struggle. His dead

body was found and carried to Limerick Cathedral to lie in state there.

The Limerick Board of Guardians paid tribute to him as having been "a

self-effacing patriot".

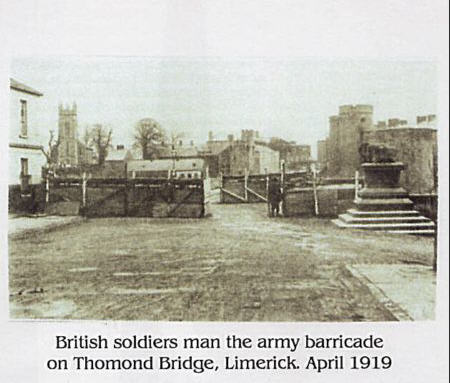

The government of the United Kingdom

could not accept such a statement without acting against it. Limerick city

was proclaimed a “special military area" under the control of the British

Army. At Byrne’s funeral, the route of the procession was lined by British

troops with fixed bayonets; the procession itself was passed by parading

armoured cars while military aeroplanes flew overhead. Two of Byrne’s

cousins were arrested and charged with murdering the constables but the

military controllers of the area doubted their ability to prove the case.

(In fact, both of them were released subsequently). Republicanism had to

be suppressed, somehow, in a city that was in many ways the most

rebellious in Ireland.

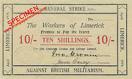

So, on Friday 11th April, a large area

in and around the Borough of Limerick was declared to be under martial law

as from the following Tuesday. The area proclaimed included all the city,

save the part of it north of the River Shannon, with the townlands of

Killalee, Monamuck, Park and Spittleland and those parts of the townlands

of Rhebogue and Singland that lay to the west of the

railway line from Limerick to Ennis.

The Workhouse

Hospital where the shooting had occurred was outside the boundary, as were

several factories including the condensed milk factory.

Anyone who wished to enter this area

could do so only if they carried permits, bearing their photographs and

signatures, that were issued by the British military on the recommendation

of the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.). No exception was

to be made for workers commuting to and from jobs that were

often outside the proclaimed area. This fact was to be declared by Sean

Cronin, the Chairman of the United Trades and Labour Council, to be the

decisive cause for the events that were about to begin.

On Saturday 12th April, the workers in

the Condensed Milk Company’s Lansdowne Factory, most of whom would be

affected by the permit order, struck work in protest against it. ‘This

initiative has been credited to Sinn Féin members amongst the workers

(Cahill, 1991) and alternatively, to Connolly’s old comrade, the

administrator of future workplace seizures, Sean Dowling, I.T.G.W.U.

organiser for the area (C. Desmond Greaves, 1982). Both accounts may be

right; political strikes were in the air after the Russian revolution.

What is certain is that neither the national leadership of Sinn Féin nor

that of the l.T.G.W.U. (or, indeed, the Labour Party and T.U.C.) played

any role in inspiring it. The union leaders were unenthusiastic about

political strikes. Sinn Féin was unenthusiastic about any strike.

It was the unions that represented most

of the Lansdowne workers- the I.T.G.W.U. and the Irish Clerical & Allied

Workers Union - that were most vehement the next day, when the United

Trades & Labour Council held a special meeting on the issue at the

Mechanics’ Institute. After an argument that lasted over two sessions

(some feared a possible food shortage would result from the decision), it

was resolved at 11.30 p.m. to call a General Strike for the city as from 5

a.m., Monday 14th. April, until the ending of martial law. At a mass

meeting to proclaim this decision, Cronin threatened, also, to call out

the railwaymen. He stated that only the 48 hours they needed to get

permission from their Executive in London prevented him from doing so

immediately. In fact, they had given notice to their Executive in London

that they would strike from Wednesday 16th April, if it gave permission.

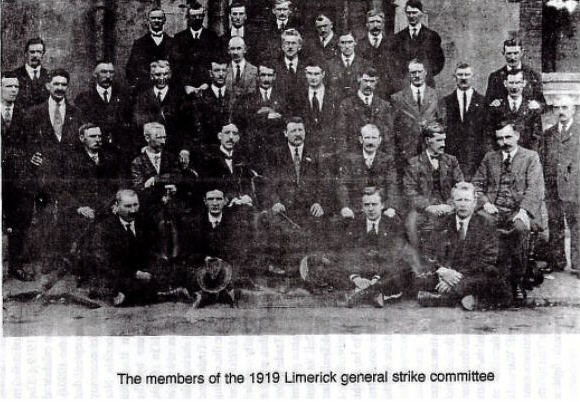

The United Trades & Labour Council

transformed itself into the Strike Committee; Cronin, as its Chairman,

remained at its head in its new form. Immediately, it took over a printing

press in Cornmarket Row, prepared placards explaining the strike, and had

them posted all over Limerick. This was the first of many publications

during the next fortnight: permits, proclamations, food price lists and a

Strike Bulletin. Besides the propaganda, the Committee detailed skeleton

staffs to maintain gas, electricity and water supplies.

The Strike is Organised

The strike had an immediate success.

Despite the suddenness of the decision, it was executed by 15,000 organised

workers. On Monday the 14th all that was operating were the public

utilities under their skeleton staffs some carriers with permits from the

Strike Committee to carry journalists to interview it, the banks, the

hotels, all government business (including the inquest on Robert Byrne) ,

the Post Office (albeit for the sale of stamps only), and the railways

(though the engineers struck work the next day).

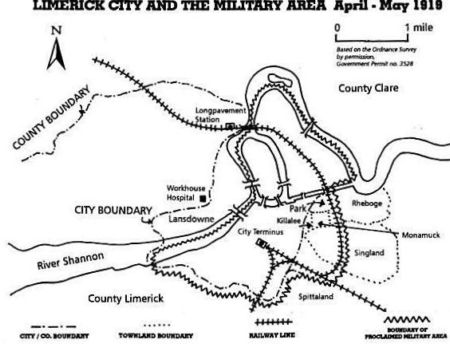

Commemorative plaque at Thomond Bridge

unveiled by

Joe Harrington, Mayor of Limerick, 2nd May 1099

These last would become a

major issue for the stoppage. The next day, the Unionist Irish Time

described the strike as a 'Soviet`, though the American journalist, Ruth Russell, describes Cronin himself having admitted proudly to the name.

Certainly, nobody challenged it at the time.

But what did this mean? Quite simply,

the Trades Council/Strike Committee had local sovereignty over

Limerick during the Soviet's

forthnight. . The city council was irrelevant and the local bourgeoisie acceped it. The petty bourgeoisie, the small shop keepers, participated

in the strike readily enough. The Committee's Chairman, Cronin, was

careful not to develop his aims beyond the immediate struggle to remove

the Military Permit Order. As in the strike against conscription the cause

was an ideal/right (in this case people's and especially worker's freedom

of movement) over and above the national issue. Further, the military

alienated the larger capitalists. General Christopher S Griffin, the

British Officer in command of the area, vetoed Messrs Cleeve's offer that

it take, hold and distribute permits on behalf of its workers. On the

14th The whole Limerick Chamber of Commerce sent to Andrew Bonar Law (the

British Unionist leader and acting Prime Minister), to Viscount French,

the Lord Lieutenant and to Griffin, a statement condemning the permit

system. Sinn Fein had to back the strike and Mayor O'Mara refused to leave

the proclaimed area for his home, preferring to stay in a hotel through

the stoppage.

Naturally, and in view of the apparent

class collaboration; the Unionist press regarded the Soviet as no more

than a front for Sinn Féin. The point is that the authority exercised

during the two weeks of the Limerick Soviet was not that of the bourgeois

city council, such as Sinn Féin had always placed at the centre of its

strategies, but that of the local trades council, a working- class body.

Of course, the l.T.G.W.U. had connections with Sinn Féin, and the union

was one of the prime movers in the strike, nonetheless, lull subservience

to Sinn Féin would have meant continuing work. The Limerick Soviet

remained a working class strategy; executed by a conscious, if

undeveloped, labour movement. Sinn Féin, conceived from the start as a

capitalist body could not have directed it.

The one member of the Strike Committee

not of the working class was the farmer, Michael Brennan, Commandant of

the East Clare Brigade of the Irish Volunteers. He was co-opted so that

the Soviet could have not only its own pickets but a body of armed men in

reserve. That this was only a contingency is shown by the fact that

Brennan was the choice. There was too much rivalry between the Limerick

brigades for them to allow any nominee from one of them to be their sole

representative; rather than have one from each, the outsider, Brennan was

appointed.

The Committee had soon to escalate the

struggle. The threatened food shortage began to appear on the first day.

Accordingly, the Committee ordered the rationing of hotel meals. In the

evening, it granted permits (to be enforced by picket) for shops to sell

bread, milk and potatoes from 2 to 5 p.m., as from the next day, and for the bakeries to maintain production.

On 15th April, it allowed the butchers

and on Wednesday 16th April, the coal merchants to open similarly. The

immediate results made it clear that more organisation was needed: fearing

shortages, the customers at the open shops staged buying sprees. By the

end of April 15th, the shops selling potatoes in the poorer parts of

Limerick had to close down. After their experience the next day, the six

largest coal merchants refused to re-open for the rest of the fortnight of

the Soviet, though the Strike Committee commandeered some of their coal.

To avoid a food shortage, the Strike

Committee established a subordinate body of four city councilors with

control over the local volunteers to organise the supply of food to

Limerick. It opened a food depot on the north bank of the River Shannon to take

supplies (mainly of milk, potatoes and butter) from the farmers of Co.

Clare, whose supply organisation was run by Fr. William Kennedy of

Newmarket-on-Fergus.

By the end of the first week the

sub-committee was promised food from elsewhere in Ireland and from trade

unions in Britain. At night, boats with muffled oars, and by day, hearses

from the Workhouse Hospital that were empty of any corpse brought the

supplies into the city. A ship that had arrived in the port was given a

permit that it might be unloaded of its cargo of 7,000 tons of grain. In

Limerick city itself the sub-committee operated four distribution depots from

which it was fixing the retail prices for its sales. It even organised the

supply of hay for cart horses. Profiteers were closed down immediately.

Eventually, the sub-committee had to set up its own sub-committee to deal

with the different aspects of its task.

Other sub-committees under directors

were established to supervise the pickets and propaganda. The first body

dealt with the pickets that executed police duties in the area; these

included enforcing the hours of trading, the regulation of queues and the

holding of permits. It enforced a ban on cars and hackney cabs that

appeared on the streets without permits and without displaying the notice

"Working Under Authority of the Strike Committee?

The story is told of an officer of the

United States Army who arrived in Limerick on his way to visit relatives

living near, but outside, the city. Alter receiving his permit, he

expressed his bewilderment at "who rules in these parts. One has to get a

Military Permit to get in, and be brought before the Soviet to get a

permit to leave".

On the more normal duties of police

work, in which they supplanted the R.I.C., the pickets sub-committee’s

success can be measured by the fact that there was no looting and,

consequently, no cases brought before Petty Sessions. Indeed, as Thomas

Farren of the Dublin Trades Council and the Labour Party National

Executive was to remark at the Drogheda Congress of the Irish Labour Party

& Trade Union Congress in August 1919, there was not a single arrest made

during the entire strike. At the end of the first week, this

sub-committee, too seems to have split in two: one for permits and one for

transport

The Propaganda sub-committee was

responsible for the Strike Committee’s publications, most notably, its

daily Workers’ Bulletin. This maintained publication throughout the period

of the stoppage, although, until Thursday 17th April, three out of the

four local (bourgeois) newspapers appeared, licensed by the Strike

Committee.

Another sub-committee was soon

established. On 18th April, Cronin announced a fund to supply the Soviet

with money as it was to need cash both for purchases from outside and to

keep its circulation inside its area. A sub-committee was established to

plan this fund. It was composed of competent accountants and employees in

the finance departments of Limerick firms.

The Strike gained international

publicity due to one coincidental fact. Preparations were being made for a

transatlantic air race, and one of the competitors therein, Major Wood,

was planning to refuel at the neighbouring Bawnmore field. Accordingly,

many reporters were in the city including representatives of the Chicago

Tribune, the Paris Matin, and the Associated Press of

America, an agency serving 750 papers. All these reporters came under the

authority of the Strike Committee. As good newspapermen, they reported the

fact.

Major Wood himself feared lest his plans

be jeopardised by the Soviet’s control of Bawnmore’s supplies. Through the

ex-Lord Mayor of Limerick, Sir Stephen Quin, he asked the Committee’s

permission to use the landing field. This permission was granted on the

understanding that he openly acknowledge it. ln practice, he did not have

to carry out his part of the bargain. On his way home England in his

plane, he crashed in the Irish Sea.

Two Powers

By Good Friday 18th April, Dual Power

(the division of Government authority) in Limerick had developed to its

fullest. On the one hand there was the British state. It had brought in an

extra 100 police at the time of the inquest on Robert Byrne. It had

considerable military forces including an armoured car on

Sarsfield Bridge and a tank

(nicknamed "Scotch and Soda"). It had the routes into the proclaimed area

barred with barbed wire. At the same time, it was careful not to show any

reluctance in granting the few permits that were demanded.

Against the colonial power was the full

force of organised labour in Limerick, albeit with the backing of Sinn

Féin. Only the largest coal merchants (with the protection of the R.I.C.)

had opposed the Strike Committee and this was less out of principle than

out of self-interest. All the other sections of the community accepted the

Committee’s rules. The public houses were closed (and stayed so throughout

the fortnight of the stoppage, thus contributing, no doubt, to the lack of

crime). On the other hand, by Good Friday, the picture house was permitted

to open, with its profits going to the strike fund. Bruff Quarter

Sessions had to be adjourned because Limerick solicitors and court

officials refused to attend. Limerick pig-buyers had absented themselves from the fairs of Nenagh and

Athlone. The farmers of the neighbourhood were accepting that, due to the

closure of the Lansdowne creamery and condensed milk factory, the price of

their milk had fallen to 1/-per gallon and that the Soviet was enforcing

its retail at 4d per quart. According to Cronin, the British Army was

affected: a Scots regiment had to be sent home hastily when it was found

that its soldiers were allowing workers to pass in and out of the city

without demanding their permits.

Already there had been one trial of

strength between the two powers. On the 17th April, Griffiin offered the

terms that he had refused Messrs Cleeve to the Limerick Chamber of

Commerce for its affiliated and shopkeepers in respect of customers. The

Chamber (which included Francis Cleeve of the said firm) referred the

terms to the Strike Committee. He appealed to the citizens of Limerick as

a whole, blaming “certain irresponsible individuals" for forcing him to

impose the permit system on the people. The Strike Committee replied that

it had no wish to take the step it had taken, but that the military

authorities had given it no alternative; to prevent others suffering the

permit system at a later date, it had no option but to move. Its statement

was backed independently by a number of the city clergy, headed by the

Bishop, Dr Denis Hallinan, who denounced the permits order as

"unwarrantable" and inconsiderate and, also, attacked the military’s

handling of Robert Byme’s funeral.

On Easter Sunday, 20th April,

they maintained their position, congratulating the citizens of Limerick on their exemplary discipline. That evening Lord Mayor O’Mara

organised a public meeting which passed unanimously motions demanding the

ending of martial law and the surrender of all foodstuffs to the Strike

Committee.

Matters could not remain thus. Either

the strikers or the British had to win (any compromise would be, in

practice, merely a form of victory for one of the two sides) or the whole

struggle would be enveloped in an escalation that might bring Irish labour

to seek state power. The most definite move in the last possible direction

would have to be taken by the railwaymen. These had given massive support

to the strike.

They were refusing to handle freight for

Limerick except where it was

permitted by the Strike Committee itself

or where it was under military guard. It was expected that they would

expend this action into a full- scale railway strike. Cronin had expected

this when the strike was called, On Good Friday, he expressed his hopes

once again. Meanwhile, the Strike Committee’s delegates were reporting to

it favourable replies to the call to spread the strike. What held them

back was the inaction of the National Executive of the Irish Labour and

Trade Union Congress. Partly because of its unwieldy nature, (the members

were drawn from all parts of the country, its current President, Thomas

Cassidy, being based in Derry nor was there any provision for a standing

committee within it), partly because of the strike’s ending of

telecommunications with Limerick, the Executive was unable to discuss the

strike immediately. On Wednesday 16th April, its Dublin members

agreed informally to send the Party & Congress Treasurer (and ideologist),

Thomas Johnson, to Limerick. What was more, after two of the strikers had brought a report of the

situation in the city, they summoned a meeting of the full Executive for

the next day.

This meeting declared that the strike

concerned the workers basic right of travel and it appealed to all workers

and people of the world to support it. But it did not make any

recommendations or call for broadening the strike, preferring to wait

until the bulk of its membership could go to Limerick. This was the beginning of Easter weekend, the next day was Good

Friday and on Easter Monday, both Cassidy and the influential Drapers

Assistants Association leader, Michael O’Lehane, had meetings of their own

unions.

So the Executive decided to remain

inactive until Tuesday the 22nd. However, Saturday’s Voice of Labour

included a stop-press report of the Soviet along with an exhortation to

workers elsewhere to “be ready" to strike in sympathy. Meanwhile,

tendencies were developing to weaken the stoppage.

Worker’s Militancy Increases.

On the 19th, (against the Mayor’s

opposition), the Resident Magistrates appealed to Griffin to extend the

boundaries of the proclaimed area. On Wednesday 23rd April, the Chamber of

Commerce discussed seriously whether its members should organise scab, as

they were beginning to be hurt by the money shortage. They decided against

it for the time being.

On Easter Monday the 21st, a major blow

was delivered in London. H.R. Stockman, speaking on behalf of the British

T.U.C. and, in particular, of those trade unions whose members were

involved in the struggle, declared it to be political and instructed the

said unions accordingly to refuse strike pay to those of their members

that were involved.

This move was denounced the next day by

Sean Cronin. He insisted that the dispute was entirely a labour question

rather than that it was an elementary right to strike for democratic

freedoms. At a higher political level, support from Britain was offered by

the tiny British Socialist Party (later the nucleus of the Communist Party

of Great Britain) and by the Independent Labour Party. Stockman himself

offered subsequently to discuss the matter with the Irish Labour Party.

However, his statement was supported particularly by me Executive of the

National Union of Railwaymen which ordered its Irish members to avoid

action unless it directed it. This was not necessarily a course of action

that was acceptable to the said members, as was shown later by its

delegates at the Drogheda annual meeting of the Irish Labour Party and

T.U.C. It did place further, isolated, onus on that body’s Executive.

While the Strike Committee was attacked

by local bourgeoisie and by British trade union bureaucrats, it had

headaches, also, from its rank and tile. Their militancy increased

steadily. On Saturday, 19th April, there was an incident when a sentry had

to disperse a crowd of boys.

On the following Monday, there was a

more serious affair. A hurling match was held at Caherdavin, on the north

bank of the Shannon, outside the area proclaimed. Many used the opportunity to "trail

their coats". On returning to the city that evening, some 300 individuals

refused to show their permits (or denied possession of such) at

Sarsfield

Bridge check-point. The sentries there were reinforced swiftly by 50

constables and the tank and armoured car. With remarkable discipline, the

protesters paraded in a circle, stopping at the checkpoint only for each

to deny possession of a permit. Later some crossed the river by boat, The

majority, including Thomas Johnson, organised a

midnight concert, dance and supper at St. Munchin’s Temperance Hall in nearby

Thomondgate. The women stayed the night at supporters’ houses, while the

men slept in the Hall or in the open.

The next day, the protesters boarded

a train for Limerick at

Longpavement station and avoided a military cordon at the city terminus by

getting out at the opposite side of the platform to where the troops were

waiting. The garrison was reinforced to prevent a repetition of this

incident. On the 23rd shots were fired by troops at the Munster Fair

Green when people avoided showing permits, but no one was hit. On the same

day too, the army used their guns against a more definite, if alleged,

attempted blockade breaker, but did not kill or wound him.

Another headache for the Strike

Committee was the shortage of money. This was reduced by gills supplied by

outside trades councils and trade unions: the I.T.G.W.U. made up for an

initial failure to send strike pay by giving fl,000 to the strike fund —

not a large sum considering its claim to have 3,500 members in the city. Gifts

were sent by various sympathisers, including the G.A.A. and the Bishop,

the Sinn Féiner, Dr. Michael Fogarty and the clergy of the Killaloe

diocese. Nonetheless, these could help out only to limited extent The

Labour Party and T.U.C. National Executive estimated, later, that £7,000 -

£8,000 per week was needed to maintain the Soviet. Only £l,500 had arrived

when it ended after a fortnight.

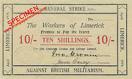

The Finance Sub-Committee worked with

Johnson to prepare designs for special bank notes to be issued on the

credit of- Limerick and its Strike Committee. Such notes to the total value of thousands

of pounds were produced in sizes of £l, £5 and IO!-. According to John

McCann, (1946) “this money was accepted by numbers of shopkeepers upon the

promise of redemption by the Trades Council."

Ultimately, these notes were redeemed

leaving a surplus from a fund that had been subscribed to by sympathisers

in all parts of Ireland”. However, other sources suggest that the strike

ended before they could be put into general use. Meanwhile, the stoppage

continued to gain support amongst the workers. On the 23rd, the clerks at

the Union workhouse joined it.

Union Bureaucrats Make Their Move

On Easter Sunday, the 20th, two more

members of the Labour Party National Executive had arrived in Limerick. That night, at the meeting called by Mayor O’Mara, Cronin offered, on

behalf of the Strike Committee, to hand power to them. lf he felt

inadequate, part of the reason was that he knew what had to be done to win

the strike and believed that the National Executive members would be able

and willing to expand the struggle. He had already talked of calling out

the railwaymen; now he declared that the National Executive would make

Limerick the headquarters of Ireland’s

national and social revolution.

The other members of the National

Executive arrived in Limerick over the two days, Tuesday and Wednesday,

22nd and 23rd April. On the latter date, they talked with the Strike

Committee far into the evening. Cronin’s hopes were dashed. The delegation

stated that it had no power to call a national General Strike without the

authority of a special conference of the Party and Congress. In any case,

such a strike could only be for a few days as, in Thomas Farren’s words,

“under the existing state of affairs they were not prepared for the

revolution".

What the delegation proposed, instead,

was at once limited and totally utopian. Johnson is reported as describing

it at Drogheda thus... "that the men and women of Limerick, who, they believed, were

resolved and determined to sacrifice much for the cause they were

lighting, should evacuate their city and leave it as an empty shell in the

hands of the military. They had made arrangements for housing and feeding

the people of Limerick if they

agreed to the Executives proposition. Many of the men in Limerick with

whom they consulted were in favour of that proposition. The Executive then

placed it before the local committee and having argued in favour of it,

left the matter in the committee’s hands. They decided against it. That

was the last word. The Executive did not go to Limerick to take out of the

hands of the Limerick Strike Committee the conduct of their own strike".

What this meant was quite simple. The

Executive was prepared to go to any lengths to avoid confrontation with

the occupying forces lest it alienate unorganised workers whose

recruitment was considered indispensable before Labour could take state

power. Although Limerick was far from the size it is now, it was still

Ireland’s fifth largest city. For the

Labour Party to organise its evacuation would have been an intolerable

burden on it. At the same time, it would not have deterred the British

Army, whose role in Limerick would have become more boring, but certainly simpler.

The only conceivable result of the

proposal would have been to ruin Labour as quickly as the national General

Strike it feared to call, without embarrassing British imperialism in the

least. The limitations of the politics of pure protest have seldom been

more evident. Quite correctly, the Strike Committee rejected this

proposal. Politically, if not elsewhere, nature abhors a vacuum. The left

had failed to use its opportunities. Now the time was ripe for the

strikers’ bourgeois allies to change sides. The evacuation scheme itself

had been inspired by a suggestion from Richard Mulcahy, Chief of Staff of

the Volunteers that the city’s women and children be evacuated. Now his

local supporters took the initiative. The day after the Executive had met

the Strike Committee, the Mayor and the Bishop of Limerick visited General

Grifflin

What happened at this meeting is

unknown. Subsequent events point to them having obtained what might have

been considered a compromise: the Soviet should end and, if for a week

after that, there was not trouble in the proclaimed area, he would

withdraw the Military Permit Order.

Faced with this offer, backed as it was

by the leaders of bourgeois Limerick, spiritual and temporal, deserted by

the National Executive of its organisation, politically, and by now, save

for Johnson, personally, the Strike Committee began to retreat.

Defeat

On the same day as the Mayor and the

Bishop met the General, it declared that strike notices were withdrawn for

those working within the boundary of the proclaimed area. For the others,

the strike would continue. Indeed, Johnson was cheered at a meeting

outside the Mechanic's Institute when he promised a special conference to

discuss the strike. The next day, he called for more financial aid.

However, and especially in Thomondgate

where the workers commuted to their jobs in the proclaimed area, there was

considerable bitterness and copies of the proclamation limiting the strike

were torn down. Many talked of a “second Soviet", threatening to refuse

permits. At Sarsfield Bridge on Saturday, 26th April, demonstrators stopped permit holders from

crossing until they were themselves dispersed by the constabulary. As yet,

only half the strikers had returned to work. The bacon-curing factories

remained closed though this was due in a pig shortage rather than permits;

they were in the proclaimed area, More significantly, the Condensed Milk

Company's factory stay closed.

Hallinan and O’Mara increased their

demands for the total ending of the strike. On the Sunday, in the pulpit

of St. Michael's, Fr William Dwan, denounced the strike as having been

called without consulting the Bishop and clergy. Even without this, the

Strike Committee could not resist the pressure. The Bishop and the Mayor

had at least some scheme of action (or rather, inaction) the Committee had

none. On the same day as Dwan’s attack, it declared the Limerick General

Strike to be at an end.

The next day, save for mills and the

bacon factories, the city was back to normal. Seven days later the

proclamation was withdrawn and permits to enter the area covered by them

were declared unnecessary as from midnight, Sunday-Monday, 4th - 5th May.

On the 10th of the same month, the Chamber of Commerce found the voice

that popular feeling had forced it to suppress. It denounced the Strike

Committee for not consulting it and for not giving adequate notice to the

city’s employers as a whole. It hinted that, had it been asked, it could

have worked with the Trades Council to take (unspecified) joint action

such as would have prevented the "disastrous strike". It remarked that if

it had acted to lock out its members' employees without consultation, the

Trades Council would have "bitterly resented it". Separately, it estimated

the strike as having caused losses of £42,000 in wages, and £250,000 in

turnover.

The Limerick Soviet’s defeat, for such

was what it was in the long run, was caused immediately by the Strike

Committee’s acceptance of bourgeoise leadership. However, this was itself

caused by the refusal of the National Executive of the Labour Party and

T.U.C. to embark on a struggle that might have caused major problems, but

which could have led to the Worker’s Republic.

In his speech to the Party’s Drogheda

Congress, Johnson was to justify this position. "'l here were times when

local people must take on themselves the responsibility of doing things

and taking the consequences, and this, he asserted, was one of them. But

when that action had been taken there must be due consideration given to

any suggestion of an enormous extension of the action. They could never

win a strike by downing tools against the British Army. But there was

always the possibility in Ireland that aggressive action on this side

might prompt aggressive action on the other side of the Channel. It was

for them as an Executive to decide whether this was the moment to act in

Ireland, whether there was a probability of a response in England and

Scotland, and their knowledge of England and Scotland did not lead them to

think that any big action in Ireland would have brought a responsive

movement in those countries.

A General Strike could have been legitimately

called in Ireland on 12 occasions within the last two years. But it was

not a question of justification It was a question of strategy. Were they

to take the enemy’s time or were they to take their own? They knew if the

railwaymen came out the soldiers would have taken on the railways the

next-day. They knew if the soldiers were put on the railways, the railways

would have been blown up. They knew that would have meant armed revolt.

Did they as trade unionists suggest that it was for their Executive to say

such action shall be taken at a particular time, knowing, assured as they

were, that it would have resulted in armed revolt in Ireland? He believed

that it was quite possible that it would be by the action of the Labour

Movement in Ireland that insurrection

would some day be developed. There might be occasion to decide on a down

tools policy which would have the effect of calling out the armed forces

of the Crown. But Limerick was not the

occasion".

Johnson’s assumptions were shared by the

vast majority of delegates present. Only D.H. O’Donnell of the Irish

Clerical and Allied Workers’ Union criticised the strategy that had been

followed. Two notable past and fixture critics of the party’s line, RT.

Daly, former Secretary of the National Executive, and Walter Carpenter of

the International Tailoring Machinists and Pressers Union, (later to be a

founder member of the Communist Party of Ireland) hastened to declare

their support for what had been done. Sean Dowling, Limerick’s I.T.G.W.U.

organiser, offered to second a vote of confidence in the National

Executive. Cronin was not present: doubtless his old suspicions of ‘Dublin

Socialists’ had been revived by his soviet experience and he could see no

point in debating them. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight, the

assumptions that guided this strategy can be seen to be incorrect. They

imply that the Limerick Soviet was a protest, and, more importantly, only

to be kept as a protest. The time for more serious action was not yet (as

Carpenter remarked). But when was it to be?

Johnson, the man who talked of the

labour movement finding its own time was the man whose strategy had kept

it from finding its own time. Now he was concurring in the I.T.G.W.U.’s

obstruction of the Irish Citizen Army without which, as a bare minimum no

time would ever be found that would be truly favourable to Irish labour.

Nor had Johnson any understanding of the political handicap that the

single organisation of the Irish Labour Party and T.U.C. had on the

development of working-class politics. Because of the dead weight

represented by the politics of thousands of raw untrained recruits who had

entered the movement on an industrial basis there was a standing excuse

for the movement’s leadership to avoid any radical political initiative.

One man who tried to deal with this

problem in the form it had taken at Limerick was MJ O’Lehane of the Irish

Drapers’ Assistants’ Association. He put a motion calling for a Special

Conference to give the Executive power to call and veto strikes (including

general strikes), to control propaganda and to pay strikers and lock-out

victims from a special levy.

Despite opposition, mainly from craft

unionists and the railway unions, this motion was carried and forgotten.

O’Lehane himself died early in 1920. In any case, simply giving such power

to the National Executive on its present basis was not the answer to

Labour’s organisational problems. When the grassroots demand was strong

enough, (as with the national General Strike on behalf of the

hunger-strikers the following year), the Executive would take such powers

without apology. Its debility lay in the fact that it was elected by the

delegates of a politically undifferentiated working-class organisation to

lead initiatives that required a politically tested revolutionary party.

So it gave support to Johnson and his

colleagues in a material situation that would prove catastrophically

wrong. Soon would come Tan War, Civil War, national partition and the

weakening of the working class, both nationally and internationally. Even

in the short run, Johnson’s prophecy of the dreadful results of national

political railway strike was to be disproved by the events of the

following year, when Irish railwaymen were to strike work on the munitions

issue in a context far less to their advantage. Neither the Irish Labour

Party nor the trade union movement - before or after its break with the

former - nor indeed the Irish Communist parties have ever come to terms

with this political failure.

As for

Limerick itself; the after

effects of the strike do not give support to the idea that the National

question got in the way of the Social question. Admittedly, there was

some superficial evidence of this. Following immediately on the end of the

strike, Limerick had to be allowed

exemption from the Irish National "holiday” (in effect a general strike)

in celebration of May Day 1919 (The only time this day has been celebrated

thus in Irish history until the 1990s). The city’s workforce accepted

that Limerick needed to get its economy back in order as soon as possible.

Nor did

Limerick see within it such

occupations of workplaces by the employees as occurred in Cork, Waterford

and in various towns in Munster and elsewhere during the succeeding four

years. Its Trades and Labour Council called for the ending of the

Munitions Strike in 19QO before the struggle was finally ended

nationally. It is also true that, when at last the Labour Party and Trade

Union Congress did decide to fight a general election for the third Dail

in June 1923, the Limerick united Trades and Labour Council did not run a

candidate, showing itself to be, in this matter, in line with the

consistent Republicans who opposed the Articles of Agreement.

Yet this evidence is more than negated

by other facts. Certainly the Limerick workers were by no means backward

in the industrial struggles during the remaining period of the War of

Independence and Civil War. Its Trade Council’s defeatist moves came only

a week before the rest of the country, after a six and a half month fight

in which the city had suffered more than any comparable one in the

country. Even more significant than the tactical withdrawal of the

Limerick workers from the May

Day holiday was the fact that, when the Condensed Milk Company’s Lansdowne

employees resumed work, their shop steward continued amongst them without

trouble, his dismissal forgotten by the company.

That the factory was not occupied in May

1922, like the other plants of the Condensed Milk Company was due to the

fact that its workers had been on strike for a month before the issue of

the dismissal notices that provoked the occupations and that Limerick was

garrisoned by the new National (Saorstat) Army which protected the

company’s property more determinedly than did the Anti-Treaty Forces,

elsewhere. The city had an organised unemployment movement and an

organised tenants movement, the latter of which organised the occupation

of houses in Garryowen in 1922. The next year, too, a strike of printers

resulted in Limerick in the strikers running their own Limerick Herald.

That the Trades Council did not contest

the 1922 general election seems to be due as much to its continuing

anti-parliamentary syndicalism (and the stimulus to this by the

spontaneous social struggles of the time) as to any Anti-Treatyite

influence. In 1923, when the workers' class struggles as well as the

national struggle were being defeated, the council ran candidates for the

twenty- six county Dail.

Even though Limerick city and county

were not soon again to play the pre-eminent role played by the city in

April 1919, this was only because they were surpassed, particularly, in

the sphere of class struggle by counties Cork and Tipperary, who were also

republican hotbeds. Limerick does not need to apologise for its Soviet. It was the leadership of

the working class movement that betrayed it (albeit buttressed by the

contemporary form of party organisation). This ensured that the Limerick

Soviet would not have the place in Irish history that its opposite number

in St. Petersburg had in the

history of Russia. Limerick’s fusion of syndicalism and nationalism

embarrassed trade unionists and nationalists alike. Indeed until its

fiftieth anniversary, its Soviet was buried from memory more completely

than the workplace occupations of the period. Between 1920 and l969 only

one chapter of one book (McCann’s War by the Irish) gave it any sort of

detailed treatment. Since 1969, matters have been different. The

seventieth and eightieth anniversary were occasions for celebration in the

city. That was only just; for two short weeks, Limerick had shown Ireland

the vision of the Workers’ Republic.

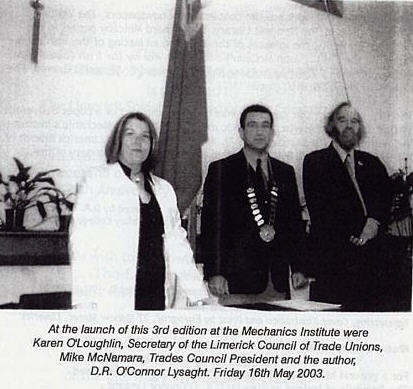

This 3rd edition of

" The Story of The Limerick Soviet "

is published by

The

Limerick Soviet Commemoration

Committee

Limerick May 2003

This committee was originally set up to

organise a weekend of activity in April 1999 to mark the 80th Anniversary

of the Limerick Soviet. We wish to acknowledge the support of The Lipman Miliband

Trust, a Socialist research and education

organisation. We would also like to acknowledge the

kind and patient support of the late Mary Hennessy of Cratloe.

"This pamphlet is a competent and

workmanlike account of the fourteen days of the Limerick Soviet O ’Connor

Lysaght gives a concise day by day account of the Soviet. Several pages

are devoted to an analysis of the political conditions of its defeat. The

pamphlet is a welcome addition to a small body of work on an important

episode in labour and national history”

Saothar

The Sources of this

work are the contemporary newspapers, The William. O’Brien papers in The

National Library, The Richard Mulcahy papers in the National University,

The minutes of the 25th Annual Meting of the Irish Labour Party and the

TUC., John McCann’s account in War by the Irish (Tralee 1946), Michael

Brennan’s The War In Clare (Dublin 1980) and C. Desmond Graves, The

History of the ITGWU. (Dublin 1982) -

The first edition of this pamphlet was

based on the text of a paper delivered by D.R. O’Connor Lysaght at a

public meeting held in the Mechanic's Institute in Limerick on 27th

September 1979, and published by the Limerick Branch of People’s Democracy

(PD.), Limerick to mark the 60th anniversary of the Soviet.

A revised second

edition was published in April 1981.

This new edition incorporates material

from a paper delivered by D.R. O’Connor Lysaght at the 11th international

Conference of the Soar Valley College Irish Studies Workshop in Leicester,

England on 26th March, 1994

Other publications on the Limerick

Soviet are :-

Liam Cahill, Forgotten Revolution,

Dublin 1991

Jim Kemmy, “The Limerick Soviet" in Limerick Socialist

ll - IX, 1973-74

Typesetting, Cover Illustration and

Print by Eurograf, 27 Mallow St, Limerick

Photography by Fintan Ward

For a general history of the Republic of Ireland, you should read

The Republic of

Ireland written by D.R. 0’Connor Lysaght , published by Mercier Press.

Publications:

Socialism made

Easy. James Connolly,

(with an

introduction by DR. O’Connor Lysaght)

The Communists and

the Irish Revolution, Volume 1,

Edited by DK

O’Connor Lysaght

Prisoners of Social

Patrnership, Craig

The above

publications available from

D.R. O 'Connor

Lysaght, 38 Clanawley Road Killester;

Dublin 5

The Committee wish

to acknowledge the solidarity and

financial support of B.A.T.U. and Mandate

D.R O'Connor Lysaght signing copies of

the 3rd edition.

Back