CHESMAYNE

![]()

Chatrang

Persian: one of the early versions of chess

derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Chaturanga’. The Arabic word ‘Shatranj’ was used after

the 7th century conquest of

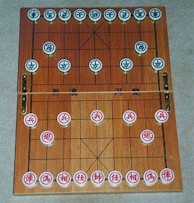

Let us compare here the Chatrang, ancestor of the European Chess,

and the Xiangqi, the

Chinese Chess.

COMMON CHARACTERS

In both games, one can

find…….

- A first row of Soldiers.

- A leader, Shah or General, at the center.

- A second , Vizier or Advisor, at his

sides.

- A pair of Chariots at the

aisles.

- A Horse beside each

Chariot.

- An Elephant or Minister beside the

Horses.

In both games, the goal is to capture the opposing KI.

Despite these similarities,

they are noticeable differences which have to be discussed now.

Board

Comparison…….

|

|

|

|

8 x 8 squares/cells |

9 x 10 intersections |

|

Plain colour |

Plain colour |

|

Sometimes, few squares/cells are

crosscut |

Important markings: a central river,

a 3 x 3 Palace at each side, points to mark the position of Soldiers

and Cannons

|

|

The MPs/mps played on the

intersections |

The board in

I plan to make a dedicated

page about ‘Ashtapada’ later on.

Even if we don’t know exactly what kind of game was played on the

Ashatapada board before 600 AD, it is certain that it was popular. Murray thought that is was

similar to several spiral

race games played in India on different board sizes (5 x 5, 7 x 7, 9 x 9), but there is no direct

evidence. The adoption of the 8 x 8

board was probably due to this popularity.

Concerning “war games”, following

In China, the most

popular games before the appearance of Chess were ‘Weiqi’ and ‘Liubo’. Weiqi was adopted by the Japanese under the

name of ‘Go’ and it is under

this name that it became one of the most strategic games in the

World. Liubo is an extinct game and it

remains very mysterious.

I plan to make a dedicated

page about ‘Liubo’ later on.

Weiqi is played on intersections, and it is

possible that this fact influenced the ancient Chinese to play their

Chess.

Liubo used a heavily marked board and it is possible that this indicates

a relation with Xiangqi. For instance, there is a central square on the Liubo

board. Is it a mere coincidence that

there is a river in the

center of the Xiangqi board? And, the

few that we know from Liubo have more to tell us. Check here in the near future!

Set

Comparison…….

|

|

|

|

16 MPs/mps |

|

|

8 Soldiers |

5 Soldiers |

|

1 General

and 2 Counsellors

|

|

|

4 pairs of

major pieces: Elephant (or Minister), Horse, Cannon, Chariot |

The number of pieces is identical in both games which is a strong

indication of a kinship. However, there

is no equilibrium between major

and minor (Soldiers)

pieces in the eastern variety.

Moreover, there are 5 and not 4 categories of major pieces in Xiangqi: the Cannon has no equivalent in western chess.

Piece by

piece comparison…….

|

|

|

|

The

King: 1 cell/step all 8 directions |

The

General: 1 cell/step, 4 orthogonal directions, within the Palace |

|

The

Vizier: 1 cell/step, 4 diagonal directions |

The

Counsellor: 1 cell/step, 4 diagonal directions, within the Palace |

|

The

Elephant: 2 cells/steps, 4 diagonal directions, can leap |

The

Minister or Elephant: 2 cells/steps, 4 diagonal directions, can

not leap, within its side of the board |

|

The

Horse: 1 cell/step straight followed by 1 diagonal, can leap |

The

Horse: 1 cell/step straight followed by 1 diagonal, can not leap |

|

|

The

Cannons: moves and captures othogonally. Moves like a Charriot,

captures by leaping over a 3rd piece. |

|

The

Chariot: slides all along lines and columns |

The

Chariot: slides all along lines and columns |

|

The

Soldier: moves 1 cell/step forward, captures 1 cell/step

diagonally forward, promotes to Vizier on last row |

The

Soldier: moves and captures 1 cell/step forward within its side of the board,

moves and captures 1 cell/step forward or beside when beyond the river |

The KI, or its

equivalent [GE],

has less mobility in the

Chinese form. This is also true for the Advisor/Vizier, the Ministers/Elephants and the Horses. The eastern Chess then looks like a blockade

game where the pieces are besieging a confined KI. It is completely different in the western chess

where the KI is unbound and really leads the operations on the

battlefield.

The PAs (Soldiers - FSs) are similar

because they go 1 step ahead but their capture mode and their promotion are very

different. That makes the biggest

difference in the structure of the two games.

In the eastern Chess, with their increase of power when they cross the river - they have a very

active role in besieging the fortress/palace. The western chess looks more like a subtle mix

between a war game and a race game - within

the battle, the PAs are racing to the last row to get to their promotion as an

officer [MP].

The use of carved pieces have been chosen in Central Asia and India

where China preferred the use of tokens bearing the name of the piece with an

ideogram. (Although carved pieces have also been used in

Old Islamic

Chessmen – Historical - religious and artistic considerations about their shape and

design.

By: Gianfelice Ferlito

Introduction

In this paper I shall dispute the theory that the old Islamic chessmen

made from the 7th to the 13th century in abstract and

stylized shapes were designed on account of the Muslim prohibition of

image. This theory attributes the

prohibition some time directly and wrongly to the Kur’an, but more often to

Muslim habits and their traditions. This

idea has generally been accepted by many chess scholars.

(1)

I shall try to clarify the complex problem of the Islamic attitude

towards representation of images as it was felt between the 7th to

the 13th century. I then shall

deal with testimonies of lslamic figures in art during the first half of the 8th

century. Among which I shall mention

those found at Qusayr ‘Amrah and at Khirbat al-Majfar in the Jordanian

desert.

I shall examine also other Islamic testimonies from Dar al Islam in

which artists have depicted

animals and men in a very realistic way for treasured gifts. Usually these were beautifully carved pieces

in ivory, works of ceramics and of metallurgy.

All these testimonies will prove that depiction of images in Islam was

not considered sacrilegious for secular palaces and for secular objects. The

Islamic prohibition against images was observed only for holy places, such as

mosques or for holy books, like the Kur’an or for the Prophets or for Allah. Theoretically, therefore, Islamic chessmen as

secular objects could have been by Muslim craftsmen in a representational way

as many other secular objects. But they

were not. This was a free choice.

From Chatrang men to Shatranj men

No one yet knows for certain how, when and where the game of chess was invented or developed from

other tabula games. Certainly the Arabs,

during their conquest of the

Many scholars often shorten the full title in “Chatrang Namak” or

“Matigan i chatrang” or “Vicarisn i chatrang”.

From that early document, it is related that such a game was devised by

a group of several wise men

of

In the Pahlavi document there is no mention of the style and design of

the chessmen, but the pieces are described by what they represent:

“Two supreme

rulers: resemble KIs (shah), selected corps to right and to left are in the

shape of chariots, [ROs] (raxv), a commander in chief is a tent (parzen), the

commander of the rearguard is an elephant, [EL] (pil), the commander of the

calvary is a horse, [KT] (asp), and the foot-soldiers (piyada), [FSs] represent

the infantry”.

(2)

Knowing that the Indian sculptures and paintings of the period were

inclined towards realistic styles, many chess scholars assumed that those

Indian pieces are also “pictorials, with naturalistic figures representing the names of the

pieces”.

(3)

But Indian chessmen of that period were, however, never found.

The famous carved ivory piece representing a KI on top of an elephant and dated

9th-10th century is certainly an Arabic work after an

Indian model as the kufic inscription testifies (“min ‘amal Yusuf al-Bahili”)

but “it is difficult to accept it as a chess pieces”.

(4)

It is quite probable that Persian Chatrang-men were realistically carved

in wood, bone, ivory, precious and semiprecious stones.

Fortunately for our knowledge of the history of chessmen, the former

(5)

Excavations in Afrosiab under the leadership of Professor Bukariov in

1977 uncovered seven ivory carved sculptures which left……. “no doubt as to the

playing purpose of the figures”.

(6)

These sculptures correspond to the roles of the Chatrang-men as

described in the old text “Vicarisn”.

According to Dr. Thomas Hyde (1636-1703), in his “De ludis Orientalibus”

(1694) in the middle on the 7th century the design of Chatrang men

was probably realistic, depicting therefore their roles. He reported an illuminating anecdote, which

has been related by a preacher of the Mosque at

Evidently Caliph ‘Ali was not acquainted with Chatrang, though some of

his subjects were already playing it.

Was ‘Ali concerned that these were small idols? From this story Dr. Hyde and many others

after him thought that the chessmen at the time of ‘Ali were representational

and pictorially carved. During the

centuries of lslamic dominance, the game of Chatrang was disseminated in all

territories of Dar al Islam which consisted of two main sectors: the West,

known as “al’ Maghrib”, and the East, generally referred to as “al

Masriq”. The first comprised the

northern coast of Africa east of

By a linguistic process of Arabization the game became known in Dar al Islam as

Shatranj and it seems that it was always played with Islamic pieces as we call

them today.

Through commercial and diplomatic contacts the game was introduced,

probably during the 8th century, directly into Al-Andalus and

The name of the game, by a process of natural adaptation to the different

languages, became Zatrikion in Bysanzium, Ajedrez in

The word “scaci”or “scachi” (plural) indicated the game of chess

itself. The Persian word ‘mat’ was

adopted with the usual terminàtion of “us” and became in Latin ‘mattus’, i.e.

mate. With great probability in the

last part of the 7th century the chessmen started to be carved by

Muslim craftsmen in abstract and geometrical shapes. Shapes which vaguely suggested the original

roles they had in Chaturanga and in Chatrang.

On Islamic attitude towards the

representation of images

In the book, “The formation of Islamic art”, Professor Oleg Grabar says: “Much has been

written about Islamic attitudes toward the arts. Encyclopedia or general works on the history

of arts simply assert that, for a variety of reasons, which are rarely

explored, Islam was theologically opposed to the representation of living

beings. While it is fairly well known

by now that the Koran contains no prohibition of such representations, the

undeniable denunciation of artists and of representations found in many

traditions about the life of the Prophet are taken as genuine expressions of an

original Muslim attitude”.

(7)

In the Kur’an there are only few passages dealing explicitly with

representations of idols, images, statues and sculptures. And none of these passages are clearly

stating any prohibition for making artistic figural representations of men or

animals. The first passage usually

quoted is in Surah 5, “The Table”, ayat 90-93.

“O

believers, wine, maysir sacrifical stones (ansab) and devining arrows are

abominations devised by Satan. Avoid

them. Perhaps you may prosper”. According to the chess scholar Prof. Duncan

Forbes (17981868): “Now, all the eminent Musalman commentators on this passage say that -

by the term images - the Prophet alluded to “the game of Chess”, and that the

interdict applied not to the game itself, in which chance had no part, but to

the little carved figures or images of men, horses, elephants etc. Then used on the board as imported from

(8)

In the first place it should be noted that historically Surah 5 was

“transmitted” to Muhammad around 631-632.

Most probably Chatrang was played in

(9)

The passage in Surah 5 is a clear prohibition to Muslims for the

adoration of any kind of religious idol.

But the Kuranic condemnation is not indiscriminately directed at all

statues and images, if these do not have any religious reference. Certainly

Moses was more explicit when he delivered to the Israelite people the famous

‘Decalogue’ on

”Do not have

any other idol beside Me (Yahweh). You

will not make any idol or any image of anything which is high in the sky nor

low on the ground nor in the water below the ground”.

(10)

Again the prohibition was intended for idols but Moses forbade

literarally any images and this fact had a negative influence on graven images

in Jewish art forever. In Surah 34, “

(11)

The shari’ah considered therefore all images, created by the hand of an

artist, poor imitations when they were depicting any living creature having a

soul (nafs) or a breath (ruh). The

artist, copying living models, could have been regarded as “guilty of trying

to usurp the creative activity of God”.

(12)

Imitations of trees, flowers, leaves were however allowed by the

ulema. To a non Muslim like me, it is

very difficult to imagine a more creative activity than these geometrical and

floral creations, arabesques and decorations in which human fantasy has no

limit.

Muslims, from the beginning of their Islam (submission to Allah), have shown a

love for liberating themselves from classic forms of a world which they

conquered and probably despised. They

re-employed forms already in use by inventing new geometrical compositions,

figuring out proportional measurements in completely abstract forms and

simplifying without ambiguity of meaning.

They expressed perfectly this tendency in the astonishing care they took

with their unique calligraphy.

Calligraphy for the Muslims was considered to be a gift of Allah as

stated in the first Surah revealed by Archangel Gabriel to Muhammad, Surah 96,

“Clots of blood”, ayah 2: “Your Lord is the Most Bountiful One, who by the pen taught man what he

did not know”. The early coarse

Arabic “Jazm” script, derived from Nebatean forms of letters, was gradually and

elegantly transformed into geomctrical graphic styles. The Kufic script emerged as the sole script

for copying the Kur’an. Calligraphy in

Islam became a science, an art which permeated the general taste of the

artistic Islamic societies, leading to ideals of geometrical perfection and

beauty. “Arab calligraphy reflected their genius and

attracted their best artistic talents”.

(13)

In my view the Islamic chessmen, made in elegant abstract forms,

were expression of such taste and style.

They were made in “abstract” design and form because they were primarily

responding to the geometrical taste of the Muslims as well as responding to the

expectations of an ‘Ideal Beauty’ already expressed in their calligraphy.

Secondly this abstract design was adopted worldwide because the chessmen of

this shape were easy to handle, well balanced for moving on the board, easy to

store, convenient to carry even on a camel and resistant to bad handling. At last but not least they are easy to make

and therefore reasonably priced. Another

reason for not accepting the conventional idea expressed by so many chess

scholars about the genesis of abstract Islamic chessmen (ie. evasion from a

supposed prohibition of images), is that so far we have not found any realistic

and pictorial Muslim chess set defying such supposed prohibition. Instead we have found many Islamic works of

art, during the same centuries, defying that supposed prohibition. And so one may wonder why such defiance was

never tried for chessmen.

The answer is that the Islamic design for chessmen was not dictated by

religious restraints on images but by a deliberate choice of a popular

propensity for simplification of shapes into abstract and geometrical forms

already well reflected in their calligraphy. The letter represented a

figurative path to ‘Ideal Beauty’ and to Allah.

Muslim chess players considered their abstract chessmen beautiful in

their simplified shapes and extremely functional to handle, with a low centre

of gravity for maintaining equilibrium on the board, with a minimal

differentiation of shapes thus enabling them to concentrate on the game without

distractions of decorative and ornamental carvings. These deliberate and free

modifications of shapes from pictorial pre-Islamic Chatrang-men (Indian,

Persian), into abstract-geometrical Shatranj-men lasted for many centuries and

not only in Dar al-Islam but even in

Old Islamic Chessmen – Historical -

religious and artistic considerations about their shape and design.

Second part

By: Gianfelice Ferlito

Some examples of realistic images in

Islamic artistic works…….

Human and animal images in Islamic art were not as rare as we will

see. We must distinguish Islamic

religious art, destined to Holy Mosques, Holy Books (Kur’an), Sacred Places,

from secular art with objects ordered by the rich of the time for personal

amusement, pleasure, display and grandeur.

Chessmen belonged from the very beginning to the category of goods and

tools made for amusement and pleasure.

We have many examples of lslamic defiance of the prohibition of images

in secular society. Among them, I cite

the realistic figurations found in Qusayr Amrah (Red Casle), east of

(14)

In this castle the interior is completely covered with wall paintings:

on the west we see an image of a Caliph seated on a throne with two attendants

at his side, above is a herd of wild asses and below acrobats and a

semi-nude girl emerging from a bathing pool.

On the south wall six figures identified as the ‘Kings of the World’

including those of Bysanzium, Persia, Abyssinia, Spain (the Visigote ruler

Roderic) are shown offering submittance to the Islamic lord, the Caliph.

(15)

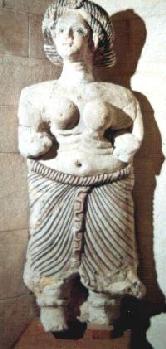

Another astonishing testimony is that of Khirbat al Mafjar at

(16)

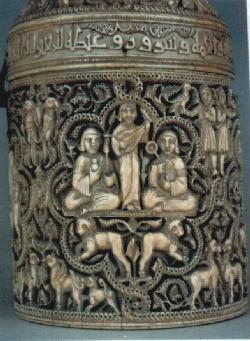

Fig.

1

Fig.

1

From 8th century, we have an Iranian silver

dish (fig. 2) with repoussé figures, to-day at the British Museum we see a

prince taking his ease in the open air with a lady and his attendant.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

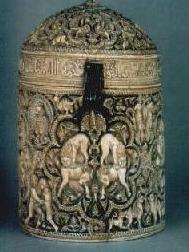

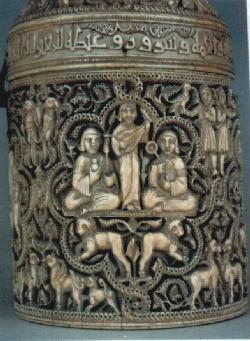

From

Al Andalus we have:

- an ivory pixies (fig. 3/4/5)

…….which was made around 968 in

The

Fig.

6

Fig.

6

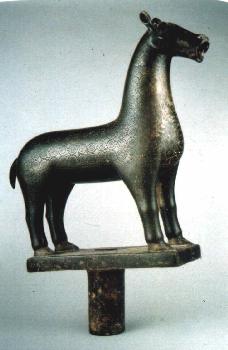

-The

Fig.

7

Fig.8

Fig.9

The

Fig.

10

Fig.

10

The Monzon lion, a bronze of

the Almohad period (12\13th century), is to-day at the Louvre. (fig.11).

Fig.

11

Fig.

11

Examples of realistic

Islamic cast bronzes were frequently found in Khurasan. These include a bird (fig.12).

Fig.

12

Fig.

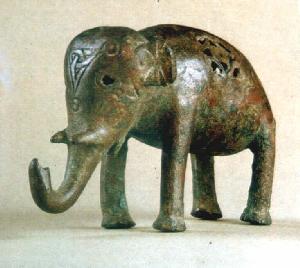

12

…….and an elephant (fig. 13).

Fig.

13

Fig.

13

The first is dated 10/11th century, the second 11\12th

century.

A large number of animals on birds in the round were made in eastern

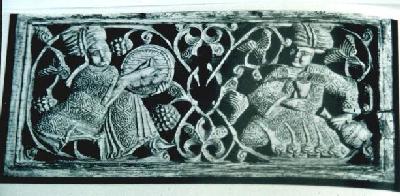

Another cast bronze with realistic figures is a jug from Jazira (

Fig.

14

Fig.

14

From

Fig.

15

Fig.

15

…….and the second at the Islamic Museum in

Fig.

16

Fig.

16

Notes:

1) Here in chronological order, a few

statements on Islamic chessmen by some chess scholars:

H. J. Murray

“The Sunnite Muslim sees a

prohibition of carved chess-pieces which actually reproduce the King elephants,

horses etc., in the prohibition of images.

Persian commentators, however have explained the term as referring to

idols, and the Shi’te and Moghul chess-players have no objection to using real

carved chessmen. The Summite player on

the contrary will only use pieces of conventional type in which it is

impossible to see any resemblance to any living creature”. (A History of Chess, Oxford 1913 p.

188).

M. D. Liddell

“From the ancient pieces that

have come down to us, there is no doubt that the earliest men represented

living forms and that the conventionalisation came from motives of economy,

from the desire for portability (too elaborated men cannot be carried in a bag

on a camel) from religious scruples”.

(Chessmen, Usa, 1937, p. 11).

H. &S. Wichmann

“The motives leading to the

creations of these novel, abstract chess pieces were religious. Since the Koran prohibits any kind of

imagery, the Mohammedans had to create new forms, which had to reinterpret in

abbreviated form the realistic-naturalistic models. This metamorphosis caused the sectional

structure of Indian sculpture to be condensed and the intricate and visually

striking outer surface to be reduced to elementary curves. The moulded mass became rounded under the

influence of the basic forms of the sphere and the cylinder”. (Chess, Munich 1964, p.16).

A. E. J. Mackett-Beeson

“Chess did not become known to

the Arabs until their conquest of Persia in the 7th century, and

therefore any reference to the game in their Sacred Book is impossible. Since the Koran strictly forbade all the

believers to handle figures in any shape or form, it is not surprising that

when chess did became known, the legitimacy of the game among the Arabs was

suspect because of its image association, and it was only after many years of

debate that judicial decision was reached.

It was finally decreed that the game of chess was perfectly legitimate

provided that chess pieces used were of simple geometric shapes, and that the

game was not played for the purpose of gambling - (Islamic) chess pieces can be

of simple form and yet pleasing to the eye; they have a delightful symmetry,

they are well balanced”. (Chessmen,

London 1968, p. 71).

F. Lanier Graham

“While the Arabs were

developing the literature of the game, they also were developing the design of

chess sets. The designs they inherited

from Persia and India in the 7th century were naturalistic

images. The Muhammadans, being extremely

fond of the game, developed an alternative.

They designed their chess pieces abstractly”. (Chess sets, New York, 1968, p.14).

C. K. Wilkinson and J. Mac Nab Dennis

“The pieces may well have been

made in a not entirely realistic manner so that they would be easy to handle in

playing. Incidentally, it is wise not

to put too much stress on the non representational character of Muslim pieces,

for the taboo on representation in things that were not strictly of

religious nature was not particularly strong, especially in Persia with its

never dying pictorial tradition”. (Chess,

East and West, Past and Present, XXVIII, 1968).

Dr. I. Linder

“Under the influence of

prohibitions, chess from the east was basically devoid of images, and instead

of battle elephants and horsemen, shahs and foot soldiers, there were symbolic

and abstract pieces”. (Chess in Old Russia,

Moscow 1975, p.28).

F. Greygoose

“The Koran forbids any form of

imagery and therefore Mohammadans were forced by their faith to turn the

Persian like figures into abstract forms”.

(Chessmen, London 1979, p. 18).

V. Keats

“The whole of Muslim art,

including the shapes of chess pieces, has been guided by the Koranic law, which

in turn derives from pre-Islamic civilization, stating that no likeness of man

may be created. Consequently, chess

pieces throughout the Muslim world have remained strikingly similar in shape,

from the advent of Islam right up to the present day”. (Chessmen for collectors, London 1985, p.

43).

C. Schafroth

“The abstraction of

naturalistic chessmen by Arabian artists was largely due to the beliefs and

tenets of Islam. The use of images was considered sacrilegious and believers

were forbidden to handle graven images.

This posed a serious problem for the Muslim chess player. The solution was to significantly abstract

the forms of the pieces. The resulting

chessmen were somewhat blocky, with knobbly projections and smoothly modelled

surfaces”. (Sculptures in miniature, Chess sets from the Maryhill Museum of

Art, Goldendale 1990, p.17).

A. Chicco

“On the other hand, it is

neither exact (to say) that the typical stylised form taken by the Arabic chess

pieces must be necessarily associated with the prohibition of the Kur’an,

which, as it is well known, forbade the images of living being. A great deal before the Hegira (622AD) the

Arabs had the opportunity to know religions which were forbidding statues and

simulacrums. There are no prejudicial

reasons which exclude a priori the existence of “stylised” chessmen even before

the Hegira or even their presence in a tomb of Roman age”. (Storia degli scacchi in Italia, Milan 1990,

p.7).

M. Pastoreau

“L’Islam en effect utilisait

des pieces stylisees, non figures, suivant en cela les principes (non

coramiques) qui interdis aux Musulmans de representer la figure humaine ou

animale. Les Occidentaux ont

d’abord utilisé ces pieces musulmanes non figurées, puis ils les ont

imithees”. (Pieces d'echecs, Paris 1900,

p. 13).

A. Sanvito

“Who ever suggested the idea

of Islamic design to the carver, surely was concerned with the aspect of

practicality and simplicity, but probably tried to convey, even in the abstract

and stylised form, the original realistic figures. The fact that before the birth of the chess

game, thought to be around the 6th-7th century many

tabula games were in existence, some of which requiring pieces whose forms may

well have influenced the chessmen models which followed. Those stylisations made in the East for

practical reasons or, maybe and more than anything else, for religious

reasons”. (Figure di scacchi, Milan

1992, p.16 and 24).

K. Whyld

“It is often said that the

shape of chessmen became simple because of Muslim religious objection to the

making of images of living creatures, but, with the exception of the relatively

recent horse’s head for the knight, this has always been the case with playing

sets. The main criteria have been

simplicity of the design and ease of production”. (The Oxford Companion to chess, London 1992,

p.76).

(2) “La letteratura Persiana” Pagliaro/Bausani,

Milan 1968, p.126.

(3) “Chess sets” Graham, New York 1968, p.13.

(4) “Pieces d’echecs” Pastoureau, Paris 1990, p.11.

(5) “Chess in old Russia”, Dr.I. Linder, Zurich. 1975, p.24/28 (6) idem,

p.24.

(7) “The creation of Islamic art” O. G. Grabar, Rev. ed.1987, p.72.

(8) “The history of chess” D. Forbes, London 1865, p.166.

(9) “Vita di Maometto” Tabari, Milano 1985, p.85.

(10) Deuteronomio, V, 7-8 (11) “Shorter Encyclopedia of Islam”, H.A.R. Gibb and

J.H. Kramers, 2nd ed. 1974.

(12) “Islamic art” B. Vrend 1991 p. 26.

(13) “Islamic calligraphy” Y. H. Safadi, p. 7.

(14) “Islamic art”, B.Brend, p.26 (15) idem, p.28.

(16) idem, p. 29.

BIBLIOGRAPHY on Islam.

The Koran, translated with notes by NJ.Dawood, Penguin books,1993.

Il Corano, translated with notes by A-Bausani, BUR, 2nd ~d ed.

1990.

“L’arte dell’Islam”, M. Dimand, Sansoni 1972.

“Historie et civilisation de l'Islam en Europe”, F. Gabrieli, Bordas

1983.

“Le arti nell’Islam”

G.Curatola e G. Scarcia, NIS 1990.

“L’arte dell’islam”, C. Du

Ry, Rizzoli 1972.

“Gli Arabi in Italia”, R. Gabrieli

e U. Scerrato, Garzanti 1985.

“Principles of Islamic

jurisprudence” M.H.Kamali, Cambridge 1991.

“L’Islam”, A. Bausani,

Garzanfi 1987.

“La sfida dell’Islam”, G.

Rizzardi, CdG 1992.

“The mediation of Ornamenti”,

Oleg Grabar, Princeton Un. Press,1992.