CHESMAYNE

Computer

think-twi

stranger in paradise

Designing a machine to play chess

In the early history of many disciplines, there has appeared an individual, who so far

outshone h/her peers, as to be remembered as the father of the discipline in

question. Hippocrates, for example, is

often referred to as the father of medicine, Thomas Aquinas as the father of philosophy or, Robert Boyle as that of chemistry.

But one figure towers above them all - the depth and breath of

Aristotle’s contribution to so many fields of thought. Aristotle was born in Macedonia in 384 BC

and was a pupil of Plato, before becoming tutor to the future Alexander the

Great. Daft as some of his ideas may

seem today, for centuries it was enough to settle any scientific argument to

announce that ‘Aristotle says.......’

“Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer”, Rembrandt

C3PO - R2-D2

audio: “super sounds of the ‘70s”

It was only with the Renaissance and

the advent of new scientific instruments that fresh ideas gained currency. But then, as Aristotle said ‘no excellent

soul is without some touch of eccentricity’.

Charles Babbage, the deviser of the first general-purpose computing

machine ‘the analytical engine’, in the mid-19th century, foresaw

that machines would one day be able to play games like chess. His device

was purely mechanical, and driven by steam.

In 1890 the Spanish scientist Torres y Quevedo created the first genuine chess-playing machine. The first attempts at designing

chess-playing machines had more to do with the realm of magic and illusion than with pure science.

It is not beyond the bounds of belief that the basic techniques for

constructing a humanoid robot capable of thinking for itself, like HAL-9000 in the

film 2001, C3PO and R2-D2 in the Star Wars films or, machines on

board the U.S.S. Enterprise (NCC-1701-D), could arise from intensive work in

programming machines to master the logical processes needed for playing

chess.

Torres y Quevedo

audio: “somebody kill me”

A more honest attempt to design a

chess playing machine was made in 1914 by Torres y Quevedo, who constructed a

device which played an endgame of KI and RO versus KI.

This machine played the side with the KI and RO and could force ++CM in a few moves however a human opponent played. Since an explicit set of rules can be given for making satisfactory moves in such an endgame, the

problem is relatively simple, but the idea was quite advanced for this

period. A chess playing ‘automan’ was made by Baron Wolfgang

von Kempelen and operated

by a hidden player (reputedly Allgaier, Vienna’s

strongest player of the day) who was ingeniously concealed in the machine. Several other chess automata were made in the

19th century.

Automaton

A mechanical device that plays

chess and operated by a human being.

These have included the Turk, Ajeeb, Mephisto and Ajedrecista.

In the 1950s computers were designed to play chess. The first and most famous is the Turk, first

unveiled in 1769. The exhibitor of

this device could open the cabinet to convince an onlooker that nobody was

hidden inside the apparatus.

Ajedrecista is presently on display at the Polytechnic Museum, Madrid. Its inventor, Torres y Quevedo, 1852-1936,

was subsidized by the Spanish government to demonstrate the possibility of inventing a machine that could play a game of chess.

Maelzel chess automaton

A device invented by von Kempelen and widely exhibited as a chess playing machine. Edgar Allan Poe wrote a paper entitled

‘Maelzel’s Chess Player’ purporting to explain its operation. Various writers concluded that the machine

was operated by a concealed human GM. A complete account of the

history and method of operation of the Automaton is to be found in a series of articles by Harkness and Battell in

‘Chess Review’, 1947.

Ajeeb

Chess automaton made by Charles

Alfred Hooper (1825-1900). This

consisted of a life sized dark-skinned Indian figure with a mobile head, trunk

and right arm, who sat on a cushion mounted on a large box. It had an elaborate clockwork mechanism

that was conspicuously wound by a large key.

A strong

chess player was concealed

inside the machine and among these were: Charles Moehle, Albert Beauregard Hodges,

Constant Ferdinand Burille and Harry Nelson Philsbury.

The inventor of the computer

There is a science fiction

fascination about computer chess, which goes back to the very first machines

which played the game. If you are at

all interested in the history of the computer you cannot help but debate the

question of who actually invented the first machine. Of course, it is not a particularly

meaningful question because reality usually cannot be summarized by a neat list

of who invented what. There is

no doubt that Babbage conceived the idea of a computing machine long before the

technology was right. After this there

are many people who claim to have built the first computer. When developments in technology started to

make creating a working computer possible it seems that a number of people

reinvented Babbage’s idea. But the real

problem with naming the actual inventor is that it is difficult to know what to

accept as the first stored program computer.

However, if you really must have an easy, clear-cut answer, why not just

accept the rule of law!

John V Atanasoff

John V Atanasoff is the inventor

of the computer, and that is a legal ruling.

He went as far as court to prove he invented the computer. Like many scientists of his time Atanasoff

had big problems with calculations. He

organized his graduate students into teams working with mechanical calculators,

but solving equations was still too slow a task. He thought of using mechanical analogue

computers of the sort that were becoming important due to the work of Vanevar

Bush but, these could only solve ordinary differential equations and Astanasoff

wanted to solve systems of partial differential equations. In short, he needed a powerful digital

computer. He realized that it would be

possible to store a bit as a high or low charge on a capacitor. A simple idea, but the problem is that the

charge leaks away. Atanasoff solved the

problem using a regeneration process he called ‘jogging’. This was the forerunner of the dynamic memory that all our present day machines rely on. He spent more than a year trying to

perfect the jogging circuit and the binary logic elements his computer would

need, and then he hired a graduate student, Clifford Berry. They worked together on the prototype

machine, which they completed in 1939.

It was an amazing machine.

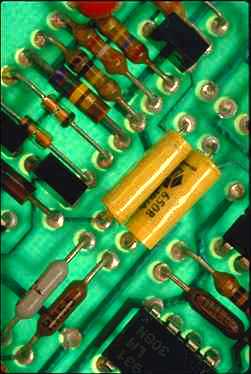

ABC: Valves, drums, capacitors and

punch cards

The logic used 300 valves and the

memory was built using drums 8 inches in diameter and 11 inches long. Each drum had capacitors mounted on it in

rows, and the charge on each was read and/or refreshed as the drum

rotated. The storage capacity was thirty

50-bit numbers per drum, roughly 1.5K. Input was via punch cards, five 15-digit

numbers per card coded in decimal. This

ABC machine never really worked as a completed computer, but worked long enough

to prove the principles but, not for long enough to solve any real

equations. They won a grant from Iowa University

who considered taking out a patent on the machine. After the 2nd World War Atanasoff

did not return to computers. He felt

that he had built a working computer and had spent enough time and energy on

the subject.

Eckert and Mauchly - ENIAC

Years later he regretted not

continuing his work. He had

misunderstood the revolutionary nature of the computer that he had built and

the impact it might have on the world.

Eckert and Mauchly got the praise for building the first electronic

computer, the ENIAC, without any mention of his pioneering efforts and the

ABC. The case finally came to court in

1970 and Atanasoff demonstrated a reconstruction of the machine to the

judge. It clearly made a big enough

impression for the decision to be made in his favor. The judgment described Atanasoff as the inventor

of the electronic computer and maintained that Eckert and Mauchly had built a

machine that derived from the ABC. The

patent was also overturned because ENIAC had been used on the H-bomb

calculations at least a year before the patent was filed. What might have been a big story went

virtually unreported due to some sleaze going on in the White House in October

1973 [‘tricky-dicky’]. Atanasoff

remained bitter that he did not get the credit he deserved. Bulgaria gave him the ‘Order of

Cyril and Methodius’, its highest scientific award. But the rest of the scientific community

has never been quite so sure. The key

question is whether or not ENIAC was derived from the ABC, as the legal ruling

states.

A chess game-tree

The idea of a machine which can

out-think, (out-compute) a human being seems to touch a mystical chord in most people. But

computers are, in practical terms, limited because chess (Chesmayne) is an infinite game. In theory

there is a limit to the number of possible moves that can be made in any position. However, the number of possible Chesmayne

games in a particular ‘chess

game-tree’ (:gt) is vast. To illustrate how

big this number is, consider that less than 1018 seconds have

elapsed since the earth was formed some 4.6 billion years ago. Even if one considers a reasonable

statistic, such as all games last 40 moves, then assuming an average choice of

30 moves per position on a D-Array (:L01), the number of games in one single :gt (game tree)

is 10120, which is more than the number of atoms in ‘our’

universe.

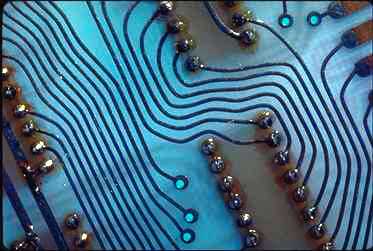

Digital computers

In Arthur C.

Clarke’s film ‘2001, A Space Odyssey’, there is a scene in which

one of the astronauts (cosmonauts, argonauts) plays :L01 of Chesmayne against the spaceships murderous onboard computer which ‘became

operational at the HAL plant in Urbana,

Illinois, on January 12th

1983’ and is soundly thrashed.......

Poole: Umm. Anyway, QU takes PA.

HAL: BS takes PA.

Poole: Lovely move, er... RO to $D01.

HAL: I’m sorry, Frank, I think you missed it. QU1 to Bishop-6. BS takes QU. KT takes

BS. ++CM.

Poole: Ah, yeah.

Looks like you’re right. I ++RS.

HAL: Thank you for an enjoyable game.

Poole: Yeah. Thank you.

[This was the end of an actual game played in Hamburg in 1913].

The school of

thought that computers will one day be the worlds strongest players of

occidental chess predated the technology which enabled the concept to be

realized by almost two hundred years, if you count the Turk, which was an

automaton chess-player, first invented and exhibited by Baron Wolfgang von

Kemplen in 1769.

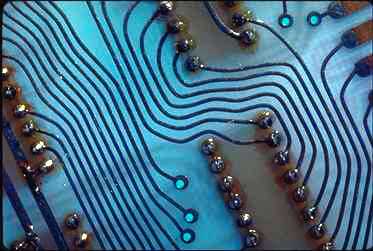

The 1950s

Machine chess-playing prehistory

gives way to history in the 1950s, about one decade after the invention of the

first electronic digital computer. Digital

computers are so called because they compute, or process information, although

that idea is somewhat misleading. They

can handle logic just as well as arithmetic and the end-product of their

calculating processes need not be a number ie, it may be words on a laser

printer or words displayed on a monitor screen - a graphic visual display or even the move of a chess MP/mp.

Information processing systems

The development of digital

computers has produced powerful tools for the study of mental processes. Because computers

are information processing systems they can manipulate information and make

decisions. Knowledge of information processing is essential if we are to understand the

tools of our thought mechanisms, and while your mind is not a digital computer when it comes to the

abstract scientific principle of information processing, there are general

rules that apply to both your mind and the computer. This information processing metaphor may be

applied to the problems confronting a chess player during play, and these would include perception, memory, thinking, decision making

and problem solving etc.

Multimedia computers

Multimedia has become the common

term for the next generation of personal computers which will transform the way

we live, work, learn, play and relate to our fellow human beings. As digital streams of sound, images and text

flow around our globe, almost every aspect of life is expected to change beyond all recognition in the near future. These machines come fitted with DVD Rom

drives which use discs similar in appearance to the music CDs you may have

in your home. The present generation

of computer DVDs, however, can each hold a huge amount of information (700mb on

a typical CD and 4+ Gigabytes on a DVD), which is equivalent to about 600

floppy disks or 4,000+ on a DVD. This

makes them ideal for storing encyclopedias, telephone directories, interactive

games, chess and astronomy databases etc. By using a

multimedia PC it is now possible to literally browse through the material

presented at the touch of a button - just like this text! For education, business or entertainment

they supply the complete answer in one neat package. The latest versions of these machines use

Pentium chips which run at blistering speeds and come complete with DVD Rom,

Hard Disk, Soundcard and speakers and may be connected to printers, VCRs (in

order to cut and paste video images), modems, fax and other devices. Word processors, spreadsheets and other

important software is pre-loaded on these computers - so all you have to do is

switch it on and away you go.

Deep Thought

This program

has defeated Tony Miles, Robert Byrne, David Levy and Bent

Larsen. It failed in its attempt to defeat Garry

Kasparov. Deep Thought Mk-1 could see 750,000 nodes of look-ahead per second, while Deep

Thought Mk-2 with IBMs assistance has increased this to 10,000,000. To beat Kasparov the objective is to create

a machine capable of seeing 1-Billion positions per second. Deep Thoughts games show that even the very

best that modern technology has to offer can not as yet dominate the world of

serious well-prepared mature chess players (GMs). In October 1989 Gary

Kasparov (world champion) played against the ‘Deep Thought’ programme.

Kasparov played from the New York Academy of Arts in Greenwich Village, while Deep Thought played in Pittsburgh via an electronic link. It was expected that Kasparov would win, but the programmers must have been disturbed by the way he did in fact

eventually win. Note: in 1994 Garry

Kasparov (Harry Weinstein) was finally beaten on :L01 of Chesmayne (traditional chess), but in 1995 he won against Fritz-4. Please see ‘Deep Thought/Blue’ for an update.

Against a human player a GM can feed off human psychology and the

opponents fear but a computer does not have any psychology.

Arithmetic operations

Chess is not just engaging, but

also one of the most sophisticated of human mental activities. Chess is so old that we cannot say when or where it was

originally invented. Billions of

games on :L01 of Chesmayne have been played and thousands of books have been written, yet the game is still fresh and new, and

particularly so, on the new

levels described in

this text. Basic arithmetic gives us

the answer why this is so. One reason

is that a machine is built to carry out arithmetic operations - the moves on the

board are arranged into a series of such operations before the program can

adequately deal with them.

A calculating robot

If you survey a board with a B-KI and B-PA at one end and an A-KI and A-PA at the other, the intervening cells being empty, you will know immediately that neither KI is in +CH. A computer is in the position

of a robot who has to carry out an arithmetic calculation to

find which cell to examine next and, having arrived there, finds instead of a MP or mp, a sheet of paper telling it which operation the

MP/mp is allowed to perform in order to reach other cells on the board. It transpires that several hundred

calculations may be needed to determine whether or not the KI is in +CH, and

even at electronic speeds the whole process can take an appreciable fraction of

a second.

A Chesmayne D-Array

On average,

each move on :L01 of Chesmayne offers a choice of about 30 possibilities and the

average total for a complete game is about 40 moves.

This means that there are about 10120 possible games on

:L01. To put this in perspective, imagine that you had a super fast computer processor which could play a million

games per second, then it would take the program about 10108 years

just to play all the games on :L01.

From this mind-boggling number we can conclude that no program could

play a perfect game of chess, but this is what makes the problem of programming

a computer so intriguing for programmers.

Your machine must play the game in human terms, that is, it must detect

the strategy and anticipate your judgments. Not having the omniscience that would allow

it to beat you no matter what occurred, it must try to out-compute and out-wit you in actual play. If you can

explain in plain language with the aid of symbols how a

calculation is to be done, then it is feasible to programme a computer to carry

out a particular calculation. A computer

when provided with the programme can make chess moves and find the solution of

a problem within these defined limits.

It is built to carry out arithmetic operations and the moves on the

board have to be broken down into a series of such operations before the

machine can deal with them.

Master players

Mature players are wo/men of

considerable intellectual ability. They have

in addition an extra latent ability. GMs who begin playing :L01 of Chesmayne early show unusual excellence at a tender age. The specific ability begins to manifest

itself around the age of nine or ten (in some cases). There are few GMs who cannot play blindfold, and play many games on :L01 at once, achievements

which are entirely beyond the powers of the ordinary mortal. The order of intellectual activity which

we are required to reduce to simple terms is therefore of a high order. This level of playing ability is called ‘genius’ [by some].

Chessmasters

GMs, to a

certain extent, talk in their own language.

This language has a vocabulary rich in content, which if understood by a

computer could make the task of programming the game easier. There are no instant experts in this game

and there appears not to be anyone on record who achieved a 2500+ rating with less than about ten years of intense preoccupation with the

game. It has been estimated that a GM

will spend 10,000 to 50,000 hours at a traditional chess board. These hours have been

compared to the time a highly literate person will spend in reading by the time

they have reached adulthood and who have vocabularies of 50,000 words at their

command. A GM will have a similar traditional western chess vocabulary.

Intelligence Quotient

Vocabulary is commonly regarded as

the best single test of IQ and tests were invented in France by Alfred Binet,

1857-1911. His tests are based on a

person’s intellectual aptitude ie: judgment, reasoning and comprehension. He produced a list of questions that could be solved regardless of belief-system, previous school

record or social class. A normal IQ is

considered to be 100. IQ is calculated

by the ratio of mental age over the chronological age. What this means is that a five-year old child may have a mental age of seven.

Many wo/men with high IQs (genius) are often failures in their academic,

personal and professional life. Shakespeare used a vocabulary of 25,000 words in his writing. Vocabulary and the ability to envisage

relationships between different words is a major factor in measuring IQ.

Goethe - Mozart - Mensa

Failure or defeat should not be

part of your chess vocabulary. Goethe

had a vocabulary of 50,000 words and he has been described as ‘The Prince of

the mind’. He is best remembered for his masterpiece ‘Faust’. In his play

‘Gotz von Berlichingen’ he described chess as the mind game ‘par excellence’, and the ‘touchstone of the intellect’. It has been

demonstrated by Dr Gordon Shaw of the Physics Department of the University of California that listening to the music

of Mozart can stimulate your mind and increase your IQ. He conducted tests on chess players and

found that their brainwaves appeared to be making music - the natural patterns of their brains were similar to musical patterns, indicating that we

need to be trained into classical music at a young age. In Britain you can join the high-IQ

society. The Los Angeles chapter of Mensa accepts as

members, only people with IQ scores of 148 and above.

The core of the human

intellectual endeavor

Chess is the intellectual game

par-excellence. Not having a chance device to muddle the contest, it pits two minds against each other in a

battle situation so complex that neither player can hope to

comprehend it entirely, but sufficiently open to analysis that each can expect to out-think h/er opponent during practical

play. Traditional chess was sufficiently deep and subtle in its implications

to have supported the rise of professional players and to have allowed a

deepening understanding through centuries of study without becoming exhausted

or barren. Such attributes mark the

game as a natural subject for attempts at mechanization. If a machine could be invented that could

play and beat a human Chesmayne player, then it seems, we would have penetrated

to the core of the human intellectual endeavor.

David Levy

David

Levy is an author and

computer chess player. He is a

Scottish IM and is one of the world’s leading authorities on

computer chess and President of the International

Computer Chess Association. His ‘computer-hostile’

playing methods made him the scourge of chess computer programmers during the

1970s and 1980s. He is the author of

‘Chess & Computers’, ‘More Chess’, ‘Computers & the Chess Computer

Handbook’ and ‘Computer Chess Compendium'.

He competed in a game in Hamburg

in 1979, in which he sat in a soundproof booth in front of a giant industrial robotic arm. This arm was connected

via a satellite, to the latest version of the Northwestern

University program Chess 4.8, running

on a CDC Cyber computer in Minneapolis. He was under orders to play interesting

chess (on :L01), and so opened with a very risky variation of the KIs

gambit. The advantage swayed back and forth, and just when he had victory in his grasp he got careless and allowed the program to ‘swindle’ him and get away with a draw. The game

lasted for about ten hours, without a break except for a few communications

failures of fairly short duration.

A programme

The complete list of instructions

or orders needed for any particular problem is referred to as a

‘programme’. Subsequences of

instructions in a programme are called ‘routines’. A chess problem, as every player knows, is

the problem of finding a move, the ‘key

move’, which will ++CM your opponent, irrespective of h/er replies, in a given number of

further moves. When a computer is

provided with a programme it can make moves and find the answer to the problem

within the limits stated above.

Artificial intelligence

:L01 of Chesmayne has been used as a test case scenario for artificial intelligence

research for over three decades.

Programming the endgame has proved to be difficult, even programming exact

play has turned out to be problematic, if ‘correct’ play is taken to mean ++CM your opponent using the rules of traditional chess. The contest can be divided

into three main sections:

:L01 programs survive the opening problems by referring to a library of openings containing the usual

book variations. During the middle

game they can also

play quite well. In the endgame phase accidents can mar their play unless a material advantage has been realized before this stage has been

reached. In the endgame the issue is

not computing ability, but trying to handle and reach a favorable

position. The objective of the

computer and a human player is to achieve ++CM, but before reaching this stage many intermediate sub

goals have to be attained. Endgames

have traditional canonical names of which the ‘Lucena Position’ and ‘Philidors Legacy’ are examples. After

programming a computer to play a game which is indiscernible from that played

by a human being, programmers have raised their sights for a new aim of being

able to beat a human GM.

A Chesmayne position

In practice you will find that you

will not follow all continuations but, only some of them and will not follow

them to the end of a game but only for a move or so. Often you will arrive at a position that is

not worth further consideration and at other times you will not hesitate in

playing a move. The further

a position is from the position in actual play the less likely it is to occur,

and you will therefore devote less time to its consideration. No two positions will have the same value and from this you can form an evaluation of the material on your particular level of play.

A position is

considered dead if there are no moves from that position and no captures or recaptures or ++CM positions discernible. Positions consist of a collection of rules of thumb and are of various types ie…….

|

01

|

What to do next

|

|

02

|

What principles to follow

|

|

03

|

What measurements to take

|

|

04

|

How to interpret these rules of thumb

and so forth

|

They form the qualifications that

enable you to make a decision. A

programmers problem is combining all these facts into a cohesive unit that will

enable the programme to play a decent game at the level chosen. The number of rules of thumb, their

complexity and the necessity for adding new rules and modifying old ones, will need a comprehensive

computer language to implement.

Defined programming

On :L01 , there

are about 30 legal moves from each position.

Two moves ahead increases this to 304. This is 810,000 continuations which are

brought into the picture. Since your

computer has no way to eliminate unlikely moves, it is forced to investigate

every possible move, until a solution is found. Even for a two-mover, the total number may

run into several thousand on average.

Since every move has to followed by a test for legality, it may consume

a few seconds, and the total move may then take longer than this. By the use of refined programming and a

faster processor, say 3 Ghz on a home computer, or both, a superlative game can be realized.

Width of the search tree

It is already known that superior

performance relies on limiting the width of the search, but what about superior

computer performance? Computer

programs, such as ‘Deep Thought’ or, ‘Chess’, written by Slate and Atkin, or

‘Belle’, written by Thompson and Condon of Bell Labs, have used a modification

of the brute force approach. These

programs can defeat all human traditional chess players including the GMs. Such programs have little ‘knowledge’ of chess per se.

Speed of computation

Like most brute force solutions

these programs emphasize speed of computation.

Such an approach has beaten GMs, but their success involves the creation

of hardware that can carry out computations further into the state-action tree

in a reasonable period of time, and hence the use of high speed

processors. Attempts have been made to

produce ‘knowledge based’ programs that limit the width of the search and ‘Paradise’ is one of these.

The Paradise

program

This program does

not play an entire game. It plays

from selected positions in the middle game.

The middle

game is the phase

in the middle of most contests where MPs/mps on the board are reduced through exchanges. Paradise

operates by examining a database of about two hundred rules. A rule is a two-part statement. The 1st part of the rule refers to

a set of conditions that may be observed on the board. The 2nd part of the rule describes

an action that may be undertaken if those conditions are met. Rules resemble the ‘if-then’ statements of

a programming language. The two hundred

rules in Paradise are organized by

higher-level actions that occur on :L01 (traditional chess). Players normally view their MPs/mps to see if

any are in immediate threat of attack and look at the cells to see if they are

safe to move into and sometimes attempt to gain access to a cell by using a

decoy to lure an opponent’s MP/mp away.

Deeper into the state-action tree

These rules are

applied to the configurations of MPs/mps on the board until a plan is formulated that has a good chance of capturing a MP or mp. If the plan does

not work or have a good chance of winning material, it is abandoned. The end

result of this decision making process is that Paradise

explores only a narrow :sat (state-action tree).

Paradise has another thing in common

with expert players. All programs have

an artificial limit to their depth of search.

Paradise searches until its objectives

have been reached.

On arriving at this stage the program considers other nodes to determine if it is worth searching still

deeper. Because the rules limit the

number of possibilities that are explored from a selected node, this program

searches into the state-action tree deeper than other programs. It trades off width of search for

depth. The ability of Paradise is

restricted by the information that can be input into the two hundred rules, and

because of this modular nature, rules can be changed without affecting other sections of the

program. Improving the Paradise

program is accomplished by editing individual rules. Therefore, future versions of Paradise will

have the ability to measure the success of special rules and to change them

where necessary.

Binary code

The nucleus of your computer is a binary code. The actual

form of storage is not important. Each

instruction contains the number of a cell, MP or, mp or other chunk of data. The computer will obey a fixed set of instructions

for manipulating these chunks of data, one by one, and will sometimes jump to

some other instruction on the programme store. By making these ‘control transfer

instructions’ dependent on certain arithmetic conditions it is possible to

leave a ‘loop’ after a specified number of times, or when a specified result

has been obtained. What this means in

practice is that a computer can read a table or directory just as you can find

a number in a telephone index ie, (in England 17+ million numbers are listed

and 22+ million copies are produced annually - each book is reissued/updated

every 18 months and is now available on CD).

Expressed mathematically, the machine can find and operate on any of the

values it finds and this is exactly the function that a

computer is good at – just in the same way that you [could] find the telephone

number of your local MP/TD Prime

Minister, the QU,

your BS/VC or, the President to explain any personal problem you may have.

Lists of tables

By

allocating different letters to the Chesmayne MPs/mps ie, KI-A, QU-B, RO-C, BS-D, KT-E, PA-F, GU-G, FS-H, AD-I, GE-J and so forth, the computer can be made to enter a

sequence dealing with MP moves when a particular stored line triggers the appropriate

monogram, and in a similar fashion to trigger mp moves when it comes across their letters. It will

now be possible to describe the essential features of the programme by means of

lists of tables consisting of chunks of information contained in successive

stored lists. The computer will go

through these lists in alphabetical or, other type of order and increase the value found

from say B to B1, then B2 at appropriate stages in the programme.

The first list

The MPs will comprise the first list numbered

consecutively ie, MP1, MP2, MP3 etc and mp1, mp2 and mp3 etc, for the mps. Therefore, each MP/mp, cell, move, rule or any other relevant chunk of data will have a

letter or combination of letter and number associated with it. It follows that each MP/mp will have a cell

number on which it is to be found. If

the MP/mp is missing (captured), another number will indicate its absence.

The second list

A

second table will contain or describe

the position in a different way ie, the number of a particular cell on the

board and the MP/mp or lack of same occupying the cell and a number indicating

whether it is :A or :B. A move from one cell to another cell is made by adding a

certain number to the original cell number, and a way of telling the computer that

the edge

of the board has been reached

will be done in the same fashion.

A table for each MP/mp

Since D25 is the number of a cell at the edge of a D-array (8 x 8

board), the computer will be

informed that the limits of the board has been reached.

For each MP/mp a separate table is used ie, the occidental

KT table will be composed

of moves 2 x 1 and a Standard-Bearer by moves composed of 3 x 1 etc. In addition the computer will be informed if

the move being made is an :A move, or a :B move. It

follows that the :B and :A MPs/mps will each have different numbers to

distinguish them from each other. By

this process the computer will try out all the available moves from a given

position until a solution is found to the problem at hand, that is, the correct

solution. If the position is legal it then carries out the move and enters it into

another table for reference when the next move is to be played. What you then have in your computer memory is a table of tables listing all possible

moves.

A master routine

Once you have arranged the problem into a numerical

format that the computer can digest, it is not difficult to arrange a scheme

causing the computer to produce a set of suitable answers. This scheme will be executed by a master

routine.

Man versus computer robots

The man versus machine argument began, in it’s modern form, in a secret

establishment set up by the British War Office at Bletchley outside London, in

the early days of World War II. As it

happened, the team of cipher experts included the two best traditional

chess players in Britain at

that time - Harry Golombek and C.H. O’Alexander. Breaking codes is a bit like playing blindfold

chess with a hidden adversary. You have to

find out what s/he is talking about, and secondly, how s/he is saying it. The technical processes were complicated

enough - but once they understood that, it was not difficult to handle. The best mathematician at Bletchley, was

Alex G. Bell. Among his many

interests was a fascination for automata and :L01 of Chesmayne. The task assigned

to the mathematicians and engineers gathered there was nothing less than

breaking the German Enigma code. The

enemy’s radio signals were intercepted and the process of deciphering them was

done by the back-room boys on machines which were the forerunners of today’s

electronic computers. One of the first

computers, Colossus, was invented to help the crypto-analysts at Bletchley to break

the Enigma codes of their opponent - Germany.

Application of computer technology

There were spin-offs in other areas also. When the problem was cracked, and in the

final months of the war Colossus was paying off in a high rate of coded messages

being broken, the panel of brains brought together had the time to reflect on and discuss other possible

applications of the computer technology that they had helped to bring onto the

world stage. Whether by accident or by

design, there were many good traditional chess players at Bletchley. Probably it had been somebody’s inspired guess that a mind trained in chess would have a special aptitude and insight for code-breaking.

Three of the people working on the Colossus project had

a special interest in chess and in the potential of machine intelligence:

I.J.Good, D. Michie and Alan Turing. Turing and Michie had great contributions to make to the

field of computer chess after the war.

Michie has had great influence on the development of research on chess,

right up to the present day and Alan Turing is renowned as a computer scientist

from the earliest era. The curious

thing about Turing was that despite his outstanding brilliance as a mathematician,

he was quite hopeless at playing :L01 of Chesmayne. This shows

that while a high IQ may well be a necessary condition for playing GM chess, it is demonstrably not enough in itself. The first recorded game between man and

machine took place some time in 1952 and was staged in Turing’s office. His notebooks/jottings are still

classified material to this very day.

Machines to play chess

After the war Turing was given a government grant to

build a general purpose electronic computer, capable of solving a variety of problems

which led in turn to his discussing the possibility of machines being able to

play an average game of Chesmayne, :L01.

He wrote a paper that described a ‘program’ that could be played on a

computer. His paper went on to

discuss how this might be brought about and the problems involved in doing

so. In the immediate post-war years,

England and the United States of America were the main pioneers in

computing. ENIAC, the first American

computer was switched on in 1946 but worked on a decimal rather than a binary system and its purpose was chiefly weapons

development calculation.

The stored program

The second American computer, EDVAC, incorporated a

crucial innovation, suggested by John von Neumann, the ‘stored program’, kept

on coded punched paper and fed into the computer when it was required to solve

the task on a particular tape. This was

the breakthrough, together with the switch to other circuits that separated the

first general purpose computers from Colossus and ENIAC. Colossus and ENIAC were dedicated (just

like some of the dedicated chess computers of today) and could not be

programmed to do any other task.

Knowledge

Knowledge is the core of information possessed by the

chess player and can be used for an intelligent understanding of the strategic problems that can confront a player during a

contest. Knowledge in itself involves more than information ie, if you

went along to a meeting of chess strategists which discussed plans for winning manoeuvres, the knowledge you possess

would not improve your playing ability one iota.

However, if the information contained in these strategies could be

adapted by the chess player then h/er knowledge could be used to good effect

during practical playing conditions.

For example, you might review the principles of chess

which would include an opening repertoire of initial moves. As you improve with practice and experience

this knowledge will be modified and instead of counting out, say, the number of

steps an occidental KT makes on the board, you will do so

unconsciously. Some of these mental

processes will require a focused attention, while others like the castling

move (%K, %Q) on :L01 will take very little attentional effort.

Chunking - Frames

Simon and Gilmartin have speculated that the typical GM has encoded about 50,000 chunks of related MPs/mps, based on an examination and analysis of MP/mp positions.

Frames are a type of script, which are data structures full of details that

can be added to or taken out at will - just like the various sentences or

paragraphs in this text which you are presently reading. It is basically a method of organizing

information ie, in the chunking analogy just cited a frame might contain slots

of information such as, GU, PA, cell, Array, Regent, KI, ++CM and so forth.

So it seems that the mature player learns some meaningful configurations

which are easy to retain in memory and work with.

This might be demonstrated using the following anagram -

‘ssgniocPre’. Now, consider the following

letters – ‘Processing’.

Hierarchies

These letters are easy to remember and form a single

unit or word. The configurations of Chesmayne

MPs/mps on the different levels of Chesmayne are treated by mature players in the

same way as the letters cited above.

Mature chess players have their knowledge organized in a hierarachical

way. In their minds, specific details are logically chunked and these

chunks are grouped into more general topics, and these into even more general

types.

Jack in the Beanstalk - Pruning the

tree

Most advanced types of problem solving occur in knowledge rich domains, where the search processes and

solutions are most likely to be narrowed down by human expertise. A mature player differs from the amateur in

many respects, but the most important way is in h/er ability to prune part of the state-action tree. One of AIs

goals is to develop software that will ‘know’ something,

in just that sense, enabling a problem solver working in consultation with the

program to trim down the size of the state-action tree. A mature chess player accumulates knowledge

resulting from years of experience with the game. This

experience has produced knowledge that is independent of the players general

cognitive functioning ie, the mature player does not explore the branches of

the state-action tree any further than a novice. This means that a mature player does not

necessarily have a better memory than the novice.

The brute-force method

What s/he does have is superior organization of the

MPs/mps on the board which operates schematically. The mature players’ mental structure not only

organizes the MPs/mps but also indicates which lines of play should be

explored. Establishing simple sub goals

can prune the branches of the state action tree, making the problem more

manageable. This is what the mature

players’ schematic knowledge enables h/er to do. Chesmayne is played at a higher level by mature players than

it is by novices, in part because the mature player does not waste time and cognitive effort exploring unproductive

avenues. For AI researchers, this

presents a problem: what exactly does the mature player know that can be

formalized into a computer program of the game? AI research using the traditional

version of chess (:L01 of Chesmayne) has taken two distinct approaches to

the problem of knowledge. The first of

these is called the ‘power approach’, because no attempt is made to mimic the

knowledge structures of a human.

Instead, the program searches as much of the state-action tree as it

can, as quickly as it can. The

computer is just taking advantage of its computational speed to find an answer to the

problem, and for this reason is said to be ‘brute-forcing a solution’. The knowledge based approach tries to

formulate an algorithm that mimics the domain-specific knowledge of the

players.

Limiting the depth of the search

How are these two approaches be applied to chess? First, no

program searches the entire state-action tree, it is just too big. This means that all programs must limit

their search operations. These

restrictions can be written into the program in two ways. A program can restrict the number of moves

that are evaluated from any point in a game. This is known as…….

01 Limiting the

depth of the search. A program may

limit the number of plays

that

are evaluated from any node in the

state-action tree that are suggested for further exploration. This is called…….

02 Limiting the

width of the search. All programs

limit depth to a certain extent, usually for the sake of time. Increasing the depth of the search by just

a single node ie, looking four moves ahead instead of three, results in a

tremendous increase in the time required to carry out all the evaluative

computations. This is usually what

happens when you increase the level of play on one of the home computer chess

programs. The program now searches

further into the state-action tree, but if you

have such a program, you know that the amount of time required by the computer

increases dramatically with each increase in level. Not all programs limit the width of

search, however, and those that do not are referred to as ‘brute force

programs’. The programs consider every legal move available on

the board at that time and consider them all out to some, usually limited

depth. Knowledge-based chess programs

on the other hand are those that try to limit the width of search.

The human brain

Your brain is designed in such a way that only a limited number

of goals are active at any one time. The reason for this is that if you were to pay

attention to all the sensory information being received at any one moment, you

would have difficulty in making a move in the first place. The point is that you can only attend to

what can be held in short term memory. This

enables you to focus on what is important and make decisions swiftly. When you try to think ahead move by move during a chess game, you have to remember to go back and explore other

possibilities after exploring the current one. If you were to take into account all

possibilities at once your mind would be overwhelmed and this would lead you to

forget what to look at next on the board.

By conscious effort it is possible to keep the last few items in memory

and be able to respond to any type of danger or, other matter of importance

that may arise on the board in the meantime.

Automatic processes

The

matter of automatic processes has also to be understood during a chess

game. The players might be involved in

conversation at the start of the game and at the same time, setting

out the board. Placing the MPs and mps on the board can be

an automatic process and makes no demand on your working memory. On inspection you might realize that your KI is in the wrong cell. The reason

for this error is that placing the MPs/mps on the board is an

automatic process. While doing this

your attention was focused on the conversation with your opponent. Reading

this text on the moves just before a contest is unlikely to improve your ability, unless of course you want to remember low level

facts such as how many cells forward a mp can move etc.

Your ability to make predictions and think of moves that will occur is limited by the

constraints on your short term memory.

Short term memory

This paradox leaves the novice player in a peculiar

dilemma. How can the mature player win most of the time if s/he cannot see all the moves

from the opening to endgame play? You will

have a number of problems to surmount if you are to achieve success. It will

be difficult for you to compare several moves and then select the correct one. Because each course of action is complex

this will strain the capacity of your short term memory to picture a single alternative and its

ramifications, let alone carry out several moves in your mind simultaneously, in order to compare one with

another. There is no precise way to

compare alternatives because the decisions made will also have to include the

reactions of your opponent who has yet to make up h/her mind about their own

reaction yet.

Mental images

Another form of representation known as a ‘mental

image’ is used by the player to distinguish, say, a MP form a mp. It is

unlikely that you have pictures stored in memory or MPs/mps cooped up inside your brain as actual images, but you clearly recognize them, so

you must have some representation of these perceptual experiences stored in

such a manner that the pattern recognition mechanism can make use of them. It is these perceptual representations that

are used in a wide range of situations during a contest. It would seem you have the information

necessary to visualize and manipulate the MPs/mps in such a way that you can

produce a plausible next move response when required to do so. This means that you can achieve ++CM, despite the obstacles introduced by your opponent and transform the mental representation in your mind

to an endgame winning scenario.

The interpretation of what your goals are, where you are in relation to them and what kind

of actions you must perform to achieve these goals are what chess is all about.

It is a problem that must be addressed by you and you alone!

Categories

If you had attended the meeting of game strategists mentioned earlier, it is assumed that you know the rules and moves of the MPs and mps. What this means is that for you there is a

connection between one move and the next, so that, in a game of chess you seek

to confirm that the next move is in fact a legal move on that particular level of play. This

concept allows you to group MPs and mps into distinct categories. You group similar objects into categories

to recognize patterns on the board that happen in some regular way. Without this ability you would not be able to carry out the advanced

thinking necessary for playing chess.

These patterns of recognition can be seen on the board where they try to

repeat actions that are followed by desirable outcomes and avoid those that

result in undesirable one’s. Therefore,

it seems that all Chesmayne players’ have knowledge represented in their minds by assembling experiences

into categories at many levels of

abstraction, and label

these groupings and use the conceptual labels as the building blocks of their

thinking processes.

Grouping - Codifying

It is possible to convey a concept using gestures, that

is, when two deaf people sit down to play chess. Signs are used from which the players can inductively

arrive at the concepts being conveyed.

Thus the function of concept making is to increase your mental

efficiency, for without the economies of categorization your information

processing system would suffer from overload. Theoretically, there are tens of trllions

of possible moves on the various boards and if you did not reduce them to a

handful of groupings, incoming information would result in overwhelming visual

static in your brain. To resolve this

you compress and codify concepts to enable you to think and communicate

effectively. This process enables the

chess player to predict what move to make next on the board. You do this by eliminating most of the

unsuitable possibilities and concentrate on those moves that have promise by

means of your ability to categorize different moves on the board.

Hierarchies

Experts have many interconnections in their minds but

they approach problems from the top down which is the key to their expertise. Research also shows that you will remember items

more effectively if they are meaningfully organized than those you see in a

random order. Mature

players who remember large and complex bodies of material often say they do so

in a hierarchical way rather than starting at the beginning and working

straight through. The reason why the

mature player is so proficient is that it takes time and experience to arrange

and rearrange what s/he knows into a hierarchical form and this can only be

achieved through practice. Due to the

narrow limit of short term memory, you will work your way through a problem in

a serial fashion, but you will not use a trial and error search that blindly

looks at every possibility in a sequential manner. You will use a selective search - not an

exhaustive search. You process incoming

perceptions of the board, and while you have a limited computing power you can

store large amounts of knowledge and retrieve it at will. This shows that the only real way a chess player can improve

h/er game is through time and experience.

Seeing

What makes a mature player more proficient than the novice? It seems that the expert player can ‘see’ things that the novice cannot. De Groot conducted a number of studies to

clarify the role of perception in problem solving. He showed his subjects, mainly chess GMs, a tactical position taken from a tournament

game that had taken place between two GMs. The subjects were asked to determine :A’s best move. Coming up

with a good move involved a lengthy analysis of the board.

De Groot compared the responses of the GMs with the players who are one

rank lower and found that the lower ranked players could analyze the board

almost as well as the GMs. However, in

a real game situation the GM would win hands down.

De Groot examined this phenomena and found that the GMs explored fewer

moves than players with less ability. De Groot

concluded that the GM players were able to see certain moves better than the

lower ranked players because their interpretation and organization of the board

was more likely to be precisely accurate.

De Groot

De Groot also asked GMs to reproduce tournament

positions from memory. He found

that they could reproduce a position of greater than twenty MPs/mps after only five seconds. They did not place the MPs/mps on the board

one at a time but in groups of four or five MPs/mps in several chunks, where

each chunk consisted of a group of MPs/mps that were somehow related to one

another. It was found that the GMs

were not using a geographical code to place the MPs/mps on the board. They were using a more abstract code which

was dependent on their extensive knowledge of MP/mp configurations. From this it can be concluded that there are

stages in skill learning.

01 The first stage

called the ‘interpretive’ stage is used to ascertain what the task of the game

involves. Performance at this level is

error prone because the

knowledge is incomplete and can overload your working memory.

02 The second

stage of skill acquisition is called the ‘compiled stage’ during which parts of

your skill are chunked or compiled into a procedure that is specific to chess

playing. Demands on working memory are

much lower because the specific knowledge ie, allowable moves, which cell to move to etc,

fall into particular areas which can be interpreted by a general

procedure.

Able to see

A program should be able to ‘see’ the same things a

human sees when it looks at a chess board. It is a well known fact onlookers see more

of the game than the players! Thus the

program requires an internal representation of the cells and the MPs and mps on

a board and the relations amongst them, and a set of processes that can pick

off and make use of these relations as needed. The former requirement is called ‘setting

up the chess board’ and the latter ‘move making and matrix making

capabilities’. The game of chess

provides an inhomogeneous collection of information out of which moves must be

forged. Thus there must be enough

variety in the representation to discriminate all the different kinds of

moves. Given that, the information

should be stored in such a way that little space is allotted to moves that

seldom occur, such as mp

promotion (#), castling (%) and so forth.

Parallel processing

Another phenomena we must consider is also perceptual,

but of a more recent discovery.

Explanations in terms of heuristic search postulate that problem solving, and cognition

generally, is a serial, one-thing-at-a-time process. Many psychologists have found this postulate implausible and have

sought for evidence that the human organism engages in extensive parallel

processing. The intuitive feeling that much information can be ‘acquired at a glance’

argues for a parallel processor. Of

course, the correctness of the intuition depends both on the amount of

information that can actually be acquired and upon what is meant by a ‘glance’. If a glance means a single eye fixation,

lasting anywhere from a fifth of a second to a half-second or longer, then we

know that there are high-speed serial processes ie, short-term memory search

and visual scanning that operate with this time range. Thus, it is certainly interesting and

relevant to find out how the human eye extracts information from a complex

visual display like a chess position and to see whether this extraction process

is compatible with the assumptions of the heuristic search theories. Experiments have confirmed the existence of

an initial ‘perceptual phase’, earlier hypothesized by De Groot, during which

the players first learn the structural patterns of the MPs/mps before they begin to look for a good

move in the ‘search phase’ of the problem solving process.

Lists

A chessboard is made up of cells, which lodge MPs/mps,

which make moves from one cell to another.

Objects in Chesmayne, like the new boards and the palettes of MPs/mps, can be represented as names of

description lists with certain prescribed associations, such as the cell from

which a MP/mp comes, the cell to which it moves, and the kind of move in

question. A Chesmayne position can be

fully described as a list of moves that originate from a standardized initial

position (ISP) and terminate in a well-defined ++CM position.

To make a move

Moves are the operators that transform one Chesmayne position into

another. What are the common properties

of chess moves? Each involves a MP/mp,

or sometimes two (as in castling), going from one cell to another. If the ‘to cell’ is already occupied, the

move is called a capture. If the

‘to cell’ is on the top rank and the mp is a PA or, other mp, it is called a promotion (#). But in

all these cases the common ‘from-to’ property holds. Four steps are required to make a move in

a game of chess…….

Configurations

The configurations of MPs/mps in chess games are treated by the mature player in the same way as you

treat the configurations of letters in sentences. In fact, many

configurations have been given names, and are quite familiar to mature players. Games follow logical sequences of moves, and

when two experts compete there are systematic patterns to the configurations. By taking advantage of these regularities, GMs appear to have superior

mental abilities in looking ahead and in planning possible moves.

But this skill is actually due to their great familiarity with the :gt (game-tree) of traditional

occidental chess, which allows

them to view configurations of MPs/mps as single psychological units.

As an example of this, ask a traditional chess player

to play :L02 of Chesmayne (using eight GUs instead of eight PAs) or, Chinese Chess and you will find that s/he will be all-at-sea

(sea-sick!). Therefore, it can be

concluded that the novice Chesmayne player will have a sporting chance [an even

playing field] of defeating an experienced traditional chess player on the new

levels of play described in this text.

Familiarity is not easy to develop.

It takes years of study, many hours each day, to reach the level of

performance of a traditional chess GM. When

skilled traditional chess players are asked to remember meaningless board

configurations, as on :L02 or :L03 of Chesmayne or, even patterns of MPs/mps taken

from the games of unskilled players, their apparent superb memory and

analytical skills deteriorate very rapidly indeed, much as your ability to

remember letters drops considerably when they no longer form meaningful words

ie,

An example of the above paragraph is

given below with all of the vowels deleted:

s n xmpl f ths, sk trdtnl chss plyr t

ply :L02 f Chsmyn r, Chns Chss nd y wll fnd tht s/h wll b ll-t-s. Thrfr, t cn be

cnclded tht th nvc Chsmyn plyr wll hv sprtng chnc f dftng trdtnl chss plyr n th

nw lvls f ply dscrbd n ths txt. Fmlrty s nt sy t dlp. t tks yrs f stdy, mny hrs

ch dy, t rch th lvl f prfrmnc f trdtnl chss GM. Whn sklld trdtnl chss plyrs r

skd t rmmbr mnnglss brd cnfgrtns, s n :L02 r :L03 f Chsmyn r, vn pttrns f

MPs/mps tkn frm th :gms f nsklld plyrs, thr pprnt sprb mmry nd nlytcl sklls

dtrrte vry rpdly ndd, mch as yr blty t rmmbr lttrs drps cnsdrbly whn thy n lngr

frm mnngfl wrds.

Decisions-Decisions - Decision making

So far, we have only examined problem-solving. Another major category of mental activity

is labeled decision making. Here, a specific

choice of alternatives is offered someone who must then select one course of

action. Decision making is a part of

problem solving, of course, just as a problem plays a role in the formal study

of decision processes, that it makes sense to examine them separately. Decisions pervade our lives (ie, whether to

vote for one party/candidate in an election or another). We are continually faced with alternative

courses of action, each of which must be evaluated for its relative merits. Sometimes, the decision depends upon the

reactions of others, often chance factors are involved and sometimes decision making is

frequently accompanied by a perplexing mixture of success and failure.

Course of action

It is a very difficult

psychological task to compare several courses of action and finally to select

one. 1st - if each course

of action has any complexity to it, it strains the limited capacity of

short-term memory

simply to picture a single alternative and its implications, let alone carry

several in mind

simultaneously in order that they might be compared with one another. 2nd - if the alternatives are

complex ones, then there is no clear way to do the comparison, even if the

several choices could all be laid out one in front of the other.

And finally, there are always a number of unknown factors (other candidates) that intrude upon the situation. Some of the results of the action are only

problematical - who knows what will really happen? Some of the results of the decision depend

upon how someone else will react to it, and often that reaction is not even

known by the other person yet. It is

no wonder that the sheer complexity of reaching a decision

often causes one to give up in despair, deferring or postponing the event for

as long as possible, sometimes making the actual final choice only when forced,

and then often without any attempt to consider all the implications of that

choice. Afterward, when all is said

and done it is too late to change the act, there is time to fret and worry over the

decision, wondering whether some other course of action would have been the

best after all - proving that time and unforeseen circumstances befall us

all.

Cognitive limitations

Human cognitive limitations interact with human

actions. Thus, in our study of human

decision making, we have to be especially concerned with realizing the distinction

between the rules people ought to follow, and those they actually do

follow. The distinction can be

difficult to make, since wo/men often describe their behavior as deliberate and

logical, even when it is not. When a

wo/man makes a decision (ie, to get married) that appears to be illogical from

the viewpoint of an outsider, usually it turns out that the decision was

sensible from the position of the decision maker, at least in terms of the

information s/he was thinking about at that time. When the apparent error is pointed out to them ie, ‘why did you move your QU there?’, ‘now I can take your BS’, they are likely to respond that they simply

‘forgot’ some important information – ‘Oh damn (or some other vernacular

expletive), I saw that earlier on, but then I forgot about it’. Which behavior do we study - the actual

erratic acts, or the systematic, purposeful ones? The answer, of course, is both.

Strategy and tactics

The word strategy is derived from the Greek strategos, a root, that originally meant ‘trick’ or

‘deception’ and was used to describe army generals, that is, a general was one who could trick the

enemy. You will notice that a trick or

ruse indicates behavior, but a trick is more than just behavior. A trick means that a mental action or plan has preceded it.

Accidental tricks are not possible (‘Jape’ means prank or trick). A Chesmayne players definition of strategy must take these aspects into account. Strategies are seen in play, but this behavior implies some type of mental

effort. A strategy can also be defined

as a move, plan, or probe designed to effect some change on the board and provides information to the

players. That is, the move is

considered informative. In Chesmayne,

strategies are of two classes…….

In computer programs, opening strategy is simulated by attaching different values to different cells on the board.

By scoring points each time a MP/mp attacks one of the four center

cells (B$A), and one point for any other cell on the board, the

programmer simulates a view of the chess board in which the edges are less important than the middle. The difficulty for the machine is to

recognize when the center of gravity of play moves from the geometrical center

of the board (B$A). A human player

knows instinctively to move h/er MPs/mps towards the sound of gunfire. The central cells of B$A may only be a

useful stopping-off point on the journey of re-deployment.

The game is divided into strategy and tactics. The best

programs are excellent tacticians. Their

calculating ability gives them an obvious superiority over most

humans. They are less adept at evaluating positions and therefore you would avoid tactics, if

possible, when playing a computer in order to defeat the programme. The strategy to adopt is to do nothing, but

to do it very carefully, because sooner or later the program will dig its own

grave. Sometimes making a bizarre

early move can confuse a program and take it out of the ‘book openings’ programmed into it.

In other words, the interactions between immediate perception and stored knowledge are themselves complex and inventive beyond anything reproducible in computers, with

their yes/no logic and essentially static memory banks. Such key concepts as advantage, sound sacrifice, and simplification by exchange, on which the choice of moves will depend, are far

too indeterminate, far too subjective and historically fluid to be rigorously

defined and formalized. The vital

parameters of psychological bluff, of time pressure, of positional feel, of tactics based on a

reading of your opponent’s personality largely elude formal notation and judgment.

They belong to the unbounded inexactitudes of art.

Four simple rules

Computers

playing to a depth of, say, 100 ply will give chess GMs a hard game and they may even get to an objectively won

game, but they will not beat a mature player because they

will not know what they are doing.

They possess too much useless information which slows down the deep tree search. Can a program ever be written which will

embody all the concepts of Chesmayne?

Mathematically, a computer can perform so many equations. If it were possible to program a computer

with everything necessary for the game of chess, it would certainly have a

chance of crushing a human being. If

you are going to play a computer, there is no reason to be scared. There are four simple rules of engagement…….

Advantage of an electronic computer

Playing chess is a problem of a much higher intellectual

order for a computer and for this reason it was possible for some early

research to be done. The main advantage

of having a computer play chess lies in its ability to perform millions of

calculations much quicker and more accurately than a human being can. It has to have the ability to look ahead to

see the ‘variations’ that can be played. Checkers was also played by machines in the 1950s for the

first time, but the main problem was that the computer found the game too

easy. It could see through a sequence

of moves and captures to the final winning or drawn

position faster than

even very strong human opponents.

However, Chesmayne has an advantage over draughts in that it has MPs of

infinite value, the KI, GE, etc which gives the game a special character for

modeling real-life processes.

Related keywords to be found in this

dictionary…….

In the early days of computer chess, at the Los Alamos Scientific

Laboratory, on the Maniac-I computer, a chess variant was implemented, to be played by the computer. The

game is described in the book ‘Computer

Chess’ by Monroe Newborn. Three

games were played, and can be found in this book, the last one against a total

novice in chess, who lost the game from the computer. If your university library does not have a

copy of this (old) book, most of what is written there about this game and

its history, can also be found in

Pritchard’s

Encyclopedia of Chess Variants.

The game is

played on a six by six board. The

opening setup is as follows…….

White:

White:

King d1; Queen c1; Rook a1, f1; Knight b1, e1; Pawn a2, b2, c2, d2, e2, f2.

Black:

King d6; Queen c6; Rook a6, f6; Knight b6, e6; Pawn a5, b5, c5, d5, e5, f5.

Pawns cannot move two steps on their first

turn. There is no castling. Other rules are as in orthodox

chess.

Jari Huikari has

made a free PC computer program that plays Los Alamos chess. You

can download it. Another computer

program, which can play Los Alamos Chess (Also by Jari Huikari) Download

it here

You can also take a look to an

experimental applet

where the game can be against oneselves, or an

applet where the computer plays against you.

Written by Hans

Bodlaender

Heuristics

Assuming that you have read the text and have played a

couple of different levels of Chesmayne, the question now arises as to what processes are

active when doing so. Having learned

how some of the new MPs/mps move you will probably have learned heuristic

principles of which the following are

examples:

Heuristics are rules that have been developed from experience in solving

problems. If you play chess, you probably know some of its heuristics, such as keeping

your QU in the center of action, keeping the KTs away from the edge of the board, and so forth. Unlike algorithms, heuristics do not guarantee the attainment of a

solution. They make up this shortcoming

by being simple and quick to use.

Cognitive scientists have discovered that the human entity often uses

several all purpose heuristics that do not appear to be closely tied to

specific problems. The origin of much

of this knowledge was the work of Newell and Simon.

A very important heuristic device is to find analogies

between the present problem and one’s for which the solution is known. Often, this requires a bit of skill in

recognizing the similarities and a bit of subterfuge in ignoring obvious

differences. Solution by analogy is

extremely valuable, even if the analogy is far-fetched. The danger, of course, is that one can think

there are similarities where in fact there are none, causing much wasted time

and effort before the error is realized and a new approach is tried. Heuristics come into play in any complex

problem-solving situation. In fact,

much of the study of thinking and problem-solving involves a search for the

kinds of heuristics people use. The

role of heuristic strategies is best understood by considering a specific

example ie, chess does not give a prescription guaranteed to lead to success. Rather,

it contains heuristic rules ie, try to control the four center cells (B$A) - make sure your KI is safe and so forth.

Subgoals

One of the main problems when playing chess is finding the particular operators that will work

in a situation. Breaking up the

overall problem into sub goals is useful for setting the problem up. The means-end analysis is useful for evaluating whether a given operator will make some progress

toward the solution. But none of these tactics tells us which operator we should be

considering. The mathematician Polya

suggests that to solve a problem we must first understand the problem and must

clearly understand the goal, the conditions imposed upon us, and the data. Second, we must devise a plan to guide us to the solution. But the crux of the matter is to devise

the appropriate plan, the operators that will, in fact, guide us toward a

solution.

Algorithms - Heuristics

In the study of problem solving, plans or operators

are divided into two types as mentioned above 1) Algorithms and 2) Heuristics. The

distinction between the two is whether the plan is guaranteed to produce the correct result. An algorithm is a set of rules which, if

followed, will automatically generate the correct solution. The rules for multiplication constitute an

algorithm. If you use them properly, you

always get the right answer.

Heuristics are more analogous to rules of thumb. They are relatively easy to use and are

often based on their effectiveness in solving previous problems. Unlike algorithms, however, heuristic methods

do not guarantee success. For many

of the more complicated and more interesting problems, the appropriate

algorithms have not been discovered and may not even exist. In these cases, we resort to heuristics.

Efficiency

In fact, the differences among

chess players seem to lie mainly in the power and efficiency of the heuristic

schemes they employ while playing the game. A good place to examine the operation of

these rules is with the last few moves

of a game, just before a ++CM

ie, an attack on your

opponent’s KI

from which it is impossible to escape.

If you consider all the possible moves and counter moves that are available

at any given stage in a chess game, there are about a thousand combinations

that could conceivably take place. The

number of possible sequences of eight moves, then, would be 10008,

which is a million billion, billion, if you care to spell it out. Were you to try to devise an algorithm for

evaluating the best one of these possible combinations, you would have to

explore literally billions of different possibilities. The sheer effort involved would overload

even the largest high-speed computer.

Selectivity

Chess players clearly do not try to follow through all

possible combinations to their conclusions.

They selectively consider only those moves that would seem to produce

important results. How do they know

which of the millions of possible moves should be considered in detail? Several studies of experts - those who have

reached the internationally recognized level of GM in traditional

occidental chess suggest that

these GMs use a number of heuristic rules to examine and select moves. The rules are ordered in terms of