CHESMAYNE

![]()

Mind

01 Sanskrit: the word ‘man’ is

derived from the Sanskrit word ‘manas’ (mind), implying no original gender

discrimination. Some people are able to

contact part of the vast field of the human unconscious (overmind). Each individual mind is a fragmentary part

of a transcendent whole.

“Measure your mind’s height by the shade it

casts!” (Paracelsus).

Self: a droplet of the Universal Mind - Godhead.

02 Mind-sports: Chess, Shogi, Go, crosswords, Monopoly, Chinese Chess,

Trivial Pursuit, Backgammon, etc are among some of the hundreds of games that

may be played. Reading books and

magazines on your favourite game is a good way to increase your knowledge. Strategical games are

testing for the mind and played by millions of people around the world.

Oyster

Catcher

Oyster

Catcher

03 Chess is the KI of board games and

many play or are fascinated by it. The

World Chess Federation (FIDE) is the largest sport organization in the world.

04 William Bill Gates’ b-1955

motto is: ‘I can do anything I put my mind to’. His wealth is based on pure intelligence not

inheritance.

05 The Magician:

the Tarot ‘I’ card. Mercury. Yellow signifies the powers of Air and the

Mind. He stands as a lightning conductor

between the planes - a bridge between the worlds. Crowned

with a band of gold. The sign of

infinity is placed above his head. He

wears the serpent girdle around his waist. His

vows: ‘to Dare, to Know, to Will and to be Silent.’

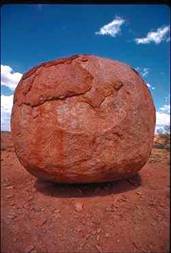

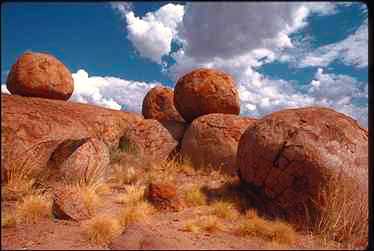

One Large

Marble – Devil’s Marbles, Northern Territory

06 The butterfly is a symbol for

the mind (the art of transformation). Egg

stage, larva stage, cocoon stage. The

final stage is the chrysalis stage and birth which demands that you use your

newfound wings - and fly. The

never-ending cycle of self-transformation.

“

07 Proverbs

23:7 ‘For as a wo/man thinks in h/her heart, so is s/he.’ The spirit communicates with God,

being the receptive device that receives knowledge and

insight from Him. The Way - the mind -

the Christ aspect of our being. The

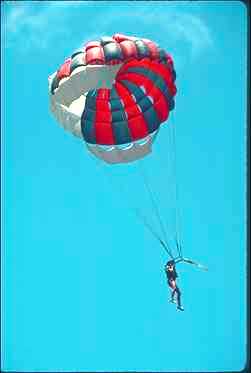

potential power of our minds is vast (infinite). “Minds are like parachutes. They only function when they are open”.

08 Aeschylus (Prometheus Bound):

‘words are the physicians of a mind diseased’.

Macbeth: ‘Canst thou

not minister to a mind diseased?’

09 A Midsummer Night’s Dream: ‘Love

looks not with the eyes, but with the mind - and therefore is winged Cupid

painted blind’.

10

11 Ghost: Ryle in ‘Concept of

Mind’, 1949: “The dogma of the Ghost in the machine maintains that there exist

both bodies and minds; that there are mechanical causes of corporeal movements

and mental causes of corporeal movements”.

12 Training for the priesthood

is mental and spiritual (equilibrium) and one of the reasons why the

preparation (paramaters) for the spiritual life (priests, rabbis,

etc) is so long and so mentally demanding.

13 That upon which we dwell in

the mind we become.

14 Prayer: the ultimate psychic

expression. Through prayer we receive

information and instruction from the Highest Source. Man’s instinct to pray is universal.

15 ‘Only the mind is real. Thought builds the soul more than deeds’.

16

17 Gothamites: symbol of the

narrow minded bourgeoisie/provincialness.

Evil Lurks in the Minds of All Good Chess Players: “There is sleight of

hand in chess... …you make your

opponent think he’s seeing everything while at the same time you make him

realize he’s not. I try to make my

moves seem only reasonable and then, at the last minute, pull the rug from

beneath my opponent’s feet, very gently so there’s a little thrill. Ah...

…now I see said the blind man”.

Many

near-death accounts involve a description of traveling through a realm that is

commonly known in NDE circles as - the void.

Together with the earthbound realm, the void is known by many religious

traditions as hell, purgatory, or outer darkness to name a few. There are many myths concerning this realm

and it is my point to also dispel some of these myths.

Summary of Insights

Concerning the Void

After

death, some souls travel very quickly through the two lower realms - the earthbound

realm and void - by means of the tunnel and on to higher realms. Other souls, particularly those who have

developed a strong addiction for some earthly desire that went beyond the

physical and into the spiritual, may enter the earthbound realm in a vain

attempt to re-enter earth. Many

near-death accounts, as you will see later, involve souls entering the void

immediately after death. From here, the

soul may then enter the tunnel toward the light in the next heavenly

realm. Other souls remain in the void

for one reason or another until they are ready to leave it.

The

general consensus among near-death reports is that the void is totally devoid

of love, light, and everything. It is a realm

of complete and profound darkness where nothing exists but the thought patterns

of those in it. It is a perfect place

for souls to examine their own mind, contemplate their recent earth experience,

and decide where they want to go next.

For

some souls, the void is a beautiful and heavenly experience because, in the

absence of all else, they are able to perfectly see the love and light they

have cultivated within themselves. For

other souls, the void is a terrifying and horrible hell because, in the absence

of everything, they are able to perfectly see within themselves the lack of

love and light they have cultivated within themselves. For this reason, the void is more than a

place for the reflection of the soul.

For some souls, it is a place for purification. In the latter case, the void acts as a kind

of time-out where troubled souls remain until they choose a different course of

action.

For

some souls, the time spent in the void may feel like only a moment. For others, it may seem like eternity. This is because the way to escape the void is

to choose love and light over the darkness.

Once this happens, the light appears and the tunnel takes them toward

the light and into heaven for further instruction. For those souls who either refuse the light

or have spent a lifetime ignoring the light, it may take what seems like eons

of “time” before they reach the point that they desire the light of love. The problem for many souls is that they

prefer the darkness rather than the light for one reason or another. For some of these souls, their only hope is

reincarnation. This is because it is not possible for any soul to be confined

in the earthbound and void realms forever.

God is infinitely merciful and would never abandon anyone to their own

spiritual agony for too long; however, God allows souls to remain there only as

long as it suits their spiritual growth.

The

void is not punishment. It is the

perfect place for all souls to see themselves and to purge themselves from all

illusions. For those souls who are too

self-absorbed in their own misery to see the light, there are a multitude of

Beings of Light nearby to help them when they freely chose to seek them. The nature of love and light is such that it

cannot be forced upon people who don’t want it.

Choosing love/light over darkness is the key to being freed from the

void. The moment the choice is made, the

light and tunnel appears and the soul is drawn into the light.

Source: The NDE and the Void - http://www.near-death.com/experiences/research15.html

The keywords below can be found in this dictionary…….

MIND

A

BAS..................................16:01

ABERGLAUBE.............................16:02

ABBERANT-ABBERATION....................16:03

ABIOGENESIS............................16:04

ABOUT-TURN

(VOLTE-FACE)................16:05

ABREACTION.............................16:06

AEGIS..................................16:07

AEON...................................16:08

AESTHETE...............................16:09

AFFLATUS...............................16:10

ALEATORY...............................16:11

ALLEGORY...............................16:12

ALTRUISM-ALTRUIST-ALTRUISTIC...........16:13

AMBROSIA...............................16:14

AMELIORATE-AMELIORATION................16:15

AMRITA.................................16:16

ANIMATISM..............................16:17

ARCANUM................................16:18

ARMAGEDDON.............................16:19

ATE....................................16:20

AXIOM..................................16:21

CASTALIA...............................16:22

CATHEXIS...............................16:23

DOUBLETHINK............................16:24

HOBSON'S

CHOICE........................16:25

MAIEUTIC...............................16:26

MAXIM..................................16:27

MELIORISM..............................16:28

MIND...................................16:29

MYSTIC.................................16:30

NOETIC.................................16:31

ORGANON................................16:32

PABULUM................................16:33

PETER

PRINCIPLE........................16:35

PHRENIC................................16:36

PLATONISM..............................16:37

PROVERB................................16:38

RELATIVITY OF

KNOWLEDGE................16:39

STREAMOF

CONSCIOUSNESS.................16:40

SUBCONSCIOUS...........................16:41

TORCHBEARER............................16:42

VISION.................................16:43

WISDOM.................................16:45

WONDER.................................16:46

ZEIGEIST...............................16:47

ACTION.................................16:48

ALEMBIC................................16:49

AMBIVALENCE............................16:50

AMUSE..................................16:51

ANT....................................16:52

ASSOCIATION OF

IDEAS...................16:53

ATARAXIA...............................16:54

ATTIC..................................16:55

AUREOLE................................16:56

BEE....................................16:57

BIRD...................................16:58

BOW AND ARROW..........................16:59

BRAIN..................................16:60

BRIDGE-BRIDGEHEAD......................16:61

BRILLANCY

PRIZE........................61:62

BRINKMANSHIP...........................61:63

CECITY.................................16:64

CLOUDS.................................16:65

COLUMN.................................16:66

CONFLICT...............................16:67

CONSCIENCE.............................16:68

COSMIC

LAW.............................16:69

CREATIVITY.............................16:70

DAEMON.................................16:71

DAIMON-DAIMONES........................16:72

DANCE..................................16:73

DEVOURED...............................16:74

DIRECTIONS (The Four

Directions).......16:75

DISINTEGRATE...........................16:76

DJINN or

Jinnee........................16:77

DREAM..................................16:78

ECSTASY................................16:79

ELIXIR OF

LIFE.........................16:80

EXCOGITATE.............................16:81

FLYING.................................16:82

GEMATRIA...............................16:83

GENIUS.................................16:84

GNOSTIC................................16:85

GREY

MATTER............................16:86

HERMAPHRODITE (Hermes and Aphrodite)...16:87

I

CHING................................16:88

IMAGINATION............................16:89

INCUBUS................................16:90

INSPIRATION............................16:91

INTUITION..............................16:92

IQ (Intelligence Quotient).............16:93

KNOWLEDGE..............................16:94

LIGHT..................................16:95

LIGHTNING..............................16:96

LITERACY...............................16:97

MADRASAH...............................16:98

MAGIC..................................16:99

MANDALA................................16:100

MANTRA.................................16:101

MEMORY.................................16:102

METHOD.................................16:103

OWL....................................16:104

PALLADIAN..............................16:105

PATTERNS...............................16:106

PEACE..................................16:107

PHILOSOPHER'S

STONE....................16:108

PHILOSOPHY.............................16:109

POLYMATH...............................16:110

PROPHET................................16:111

PSYCHIC

POWERS.........................16:112

PUSILLANIMITY..........................16:113

PUZZLE.................................16:114

QUANDARY...............................16:115

AUTEXOUSY..............................16:116

SACRED

GEOMETRY........................16:117

SAGACIOUS..............................16:118

SAGE...................................16:119

SANGFROID..............................16:120

SAVANT.................................16:121

SEEING.................................16:122

SEER-SEERESS...........................16:123

SOCIAL

MORALITY........................16:124

SPORTING

PLAY..........................16:125

STATUES................................16:126

SUBLIMATE..............................16:127

TABU-TABOO.............................16:128

TAOISM.................................16:129

THINKER

(The)..........................16:130

THOTH..................................16:131

THRONE.................................16:132

TRUTH..................................16:133

ULEMA..................................16:134

URNA...................................16:135

UTOPIA.................................16:136

VIRTUOSO...............................16:137

WAR....................................16:138

WAR OF

NERVES..........................16:139

WELTANSICHT............................16:140

WIT....................................16:141

WITAN..................................16:142

WIZARD.................................16:143

ABRACADABRA............................16:144

ALCHEMY................................16:145

APHORISMS..............................16:146

ARISTOTELIAN...........................16:147

ARRIERE-PENSEE.........................16:148

ART....................................16:149

DOME OF THE

ROCK.......................16:150

KABBALAH...............................16:151

KALOPSIA...............................16:152

KARMA..................................16:153

LEITMOTIF..............................16:154

LOVE...................................16:155

LYCEUM.................................16:156

MALAPROP...............................16:157

MOUSE..................................16:158

MYSTERY................................16:159

OXYMORON...............................16:160

PARTIE

PRIS............................16:161

POWER..................................16:162

PYRRHONISM.............................16:164

QUODLIBET..............................16:165

RESIPISCENCE...........................16:166

RIPOSTE................................16:167

ROLAND FOR AN

OLIVER...................16:168

SANHEDRIN..............................16:169

SATIRE.................................16:170

SCHADENFREUDE..........................16:171

Thought

Covert symbolic responses to

intrinsic (arising from within) or extrinsic (arising from the environment)

stimuli. Thought, or thinking, is

considered to mediate between inner activity and external stimuli.

Depending on the relative intensity of intrinsic and

extrinsic influences, thinking can be expressive (imaginative and full of

fantasy) or logical (directed and disciplined). Other terms for the two aspects of thinking

are, respectively, autistic (subjective, emotional) and realistic (objective,

externally directed). Both types of

thinking are involved in normal adjustment.

Realistic

thinking. Logical, or realistic, thought

includes convergent thought processes, which require the ability to assemble

and organize information and direct it toward a particular goal; judgment, the discrimination

between objects, items of information, or concepts; problem solving, a more

complex form of realistic thinking; and creative thinking, the search for

entirely new solutions to problems.

Autistic

thinking. Thought that is characterized by

a high level of intrinsic influence and a low level of extrinsic influence

includes free association, the giving of unconstrained verbal response to

stimuli, found helpful in bringing repressed or forgotten experiences to

consciousness; fantasy, characterized by sensory imagery in which a person

loses contact with the environment, and ranging from vague reveries to vivid

images; marginal states of consciousness, such as those experienced just before

falling asleep or those induced by drugs; dreaming (see dream);

and pathological thinking, which may be the result of

antisocial behaviour disorders, neuroses (see psychoneurosis),

or psychoses (see psychosis). The latter is characterized by major

distortions in thinking and the lack of a realistic relation to the external

environment.

Theories of thought and thought processes have

concentrated on directed thinking, in which thinking is organized in order to

solve a problem. Theories have been

concerned with both the elements of thought and with the procession of

elements.

According to one view, the elements organized by

thinking are very weak nerve impulses sent to various muscles

such that if the impulses were stronger, they would cause

overt behaviour. At first it was thought

that these impulses were primarily sent to the muscles used for speaking, so

that thinking was seen as a kind of unexecuted speech; evidence that other

muscles also receive very weak impulses during thinking led to the so-called

peripheral theory, which holds that thinking goes on in the entire body by

means of implicit muscular activities.

In the last few decade’s psychologists have come to give more credence

to so-called centralist theories, which hold that the locus of thinking is the

brain, and that the implicit muscular activity is, in effect, a

by-product.

There are other conceptions of the elements of thought

that regard them in more mentalistic terms.

The Gestalt

theorists of the 1920s and 1930s believed the elements to be of the nature of

patterns elicited from experience. A

more contemporary approach, influenced by the development of computers,

considers the elements of thought as bits of information undergoing

processing.

At the beginning of this century the

early behaviourists

suggested that thought proceeded by association. The basic principles of association are

similarity and contiguity, whereby an idea of something is followed by an idea

of a similar or related thing.

A later, more sophisticated view that thinking proceeds

according to the whole of a situation was emphasized by the Gestalt

psychologists. They argued against the

turn-of-the-century view that thinking proceeds by an internal process of

trial-and-error, whereby a thinker imagines various responses to a stimulus,

eliminates those that are inappropriate, and thus gradually comes to a final

response. By contrast, the Gestalt

theorists held that the solution to a problem comes as the result of a sudden

insight into the nature of the problem as a whole. Around 1950, however, evidence was found that

integrated these two views, by suggesting that the thinker must become familiar

with a problem through trial-and-error before being able to grasp its structure

as a whole.

Stimulated by advances in computer science, researchers

have become concerned not simply with which thought element follows which, but

also with operations that shift one element to the next. It is argued that these operations exploit a

kind of controlled trial-and-error: in what is called a heuristic approach, the most promising avenues of solution to a

problem are attempted first. Another

topic of current interest concerns the motivations for thinking.

According to the Gestalt (see Gestalt psychology) theorists, the motivation

arises when a person experiences a “gap” in his or her overall conception of a

situation. A similar view is held by

neobehaviourists, who note that there are affective (emotional) rewards for

resolving inconsistencies between thoughts.

Click here for a list of other articles that contain

information on this subject

|

|

Thought Elements of thought The prominent use of words in thinking (“silent speech”) has encouraged

the belief, especially among behaviourist and neobehaviourist

psychologists, that to think is to string together linguistic elements

subvocally. Early experiments (largely

in the 1930s) by E. Jacobson and L.W. Max revealed that evidence of thinking

commonly is accompanied by electrical

activity in the muscles

of the thinker’s organs of articulation.

This work later was extended with the help of more sophisticated

electromyographic equipment, notably by A.N. Sokolov. It became apparent, however, that the

muscular phenomena are not the actual vehicles of thinking but represent

rather a means of facilitating the appropriate activities in the brain

when an intellectual task is particularly exacting. The identification of thinking with speech

was assailed by L.S. Vygotski

and by J. Piaget,

both of whom saw the origins of human reasoning in the ability of children to

assemble nonverbal acts into effective and flexible combinations. These theorists insisted that thinking and

speaking arise independently, although they acknowledged the profound

interdependence of these functions, once they have reached fruition. Following different approaches, a 19th-century Russian

physiologist (I.M. Sechenov), the U.S. founder of the

behaviourist

school of psychology (J.B.

Watson), and a 20th-century Swiss developmental psychologist

(Piaget) all arrived at the conclusion that the activities that serve as

elements of thinking are internalized or fractional versions of motor

responses; that is, the elements are considered to be attenuated or curtailed

variants of neuromuscular processes that, if they were not subjected to

partial inhibition, would give rise to visible bodily movements. Sensitive instruments can indeed detect faint activity in various parts

of the body other than the organs of speech; e.g., in a person’s limbs when the movement is thought of or

imagined without actually taking place.

Such findings have prompted statements to the effect that we think

with the whole body and not only with the brain, or that

“thought is simply behaviour

- verbal or nonverbal, covert or overt” (B.F. Skinner). The logical outcome of these and similar

statements was the peripheralist view (Watson, C.L. Hull)

that thinking depends on events in the musculature, feeding proprioceptive

impulses back to influence subsequent events in the central nervous system,

ultimately to interact with external stimuli in determining the selection of

a course of overt action. There is,

however, evidence that thinking is not precluded by administering drugs that

suppress all muscular activity.

Furthermore, it has been pointed out (e.g., by K.S. Lashley) that thinking, like other more-or-less

skilled activities, often proceeds so quickly that there is simply not enough

time for impulses to be transmitted from the central nervous system to a

peripheral organ and back again between consecutive steps. So the centralist view that thinking

consists of events confined to the brain (though often accompanied by

widespread activity in the rest of the body) was gaining ground in the third

quarter of the 20th century.

Nevertheless, each of these neural events can be regarded both as a

response (to an external stimulus or to an earlier neurally mediated thought

or combination of thoughts) and as a stimulus (evoking a subsequent thought

or a motor response). The elements of thinking are classifiable as “symbols” in accordance

with the conception of the sign process (“semiotic”)

that has grown out of the work of some philosophers (e.g., C.S. Peirce, C.K. Ogden, I.A. Richards, and C.R. Morris)

and of psychologists specializing in learning (e.g., C.L. Hull, N.E. Miller, O.H. Mowrer, and C.E.

Osgood). The gist of this conception

is that a stimulus event ‘x’

can be regarded as a sign representing (or “standing for”) another event ‘y’ if ‘x’ evokes some part, but not all, of the behaviour

(external and internal) that would have been evoked by ‘y’ if it had been present. When a stimulus that qualifies as a sign

results from the behaviour of an organism for which it

acts as a sign, it is called a “symbol”.

The “stimulus-producing responses” that are said to make up thought

processes (as when one thinks of something to eat) are

prime examples. This treatment, favoured by psychologists of the stimulus-response

(S-R) or neo-associationist current, contrasts with that of the various cognitivist

or neorationalist theories. Rather

than regarding the components of thinking as derivatives of verbal or

nonverbal motor acts (and thus subject to laws of learning and

performance that apply to learned behaviour in general), adherents of such

theories see them as unique central processes, governed by principles that

are peculiar to them. These theorists

attach overriding importance to the so-called structures in which “cognitive”

elements are organized. Unlike the

S-R theorists who feel compunction about invoking unobservable intermediaries

between stimulus and response (except where there is clearly no other

alternative), the cognitivists tend to see inferences, applications of rules,

representations of external reality, and other ingredients of

thinking at work in even the simplest forms of learned behaviour. The Gestalt

school of psychologists held the constituents of thinking to be of

essentially the same nature as the perceptual patterns that the nervous

system constructs out of sensory excitations.

After mid-20th century, analogies with computer

operations acquired great currency; in consequence, thinking frequently is

described in terms of storage, retrieval, and transmission of items of

information. The information in

question is held to be freely translatable from one “coding” to another

without impairing its functions. The

physical clothing it assumes is regarded as being of minor importance. What

matters in this approach is how events are combined and what other

combinations might have occurred instead.

The

process of thought According to the classical empiricist-associationist view, the

succession of ideas or images in a train of thought is determined by the laws

of association.

Although additional associative laws were proposed from time to time, two

invariably were recognized. The law of

association by contiguity

states that the sensation or idea of a particular object tends to evoke the

idea of something that has often been encountered together with it. The law of association by similarity

states that the sensation or idea of a particular object tends to evoke the

idea of something that is similar to it. The early behaviourists, beginning with

Watson, espoused essentially the same formulation but with some important

modifications. The elements of the

process were conceived not as conscious ideas but as fractional or incipient

motor responses, each producing its proprioceptive stimulus. Association by contiguity and similarity

were identified by these behaviourists with the

Pavlovian principles of conditioning and generalization. The Würzburg school, under the leadership of Külpe,

saw the prototype of directed thinking in the “constrained-association”

experiment, in which the subject has to supply a word bearing a specified

relation to a stimulus word that is presented to him (e.g., an opposite to an adjective, or the capital of a

country). Their introspective

researches led them to conclude that the emergence of the required element

depends jointly on the immediately preceding element and on some kind of

“determining tendency” such as Aufgabe

(“awareness of task”) or “representation of the goal”. These latter factors were held to impart a

direction to the thought process and to restrict its content to relevant

material. Their role was analogous to

that of motivational factors – “drive stimuli”, “fractional anticipatory goal

responses” - in the later neobehaviouristic accounts of reasoning

(and of behaviour in general) produced by C.L. Hull and his followers. The determination of each thought element by the whole configuration of

factors in the situation and by the network of relations linking them was

stressed still more strongly in the 1920s and 1930s by the Gestalt

psychologists on the basis of W. Köhler’s

experiments on “insightful” problem solving by chimpanzees, and on the basis

of later experiments by M. Wertheimer and of K. Duncker on human

thinking. They pointed out that the

solution to a problem commonly requires an unprecedented response or pattern

of responses that hardly could be attributed to simple

associative reproduction of past behaviour or experiences. For them, the essence of thinking lay in

sudden perceptual

restructuring or reorganization, akin to the abrupt changes in appearance of

an ambiguous visual figure. The Gestalt theory has had a deep and far-reaching impact, especially

in drawing attention to the ability of the thinker to discover creative,

innovative ways of coping with situations that differ from any that have been

encountered before. This theory,

however, has been criticized for underestimating the contribution of prior

learning and for not going beyond rudimentary attempts to classify and

analyze the structures that it deems so important. Later discussions of the systems in which

items of information and intellectual operations are organized have made

fuller use of the resources of logic and mathematics. Merely to name them, they include the

“psychologic” of Piaget, the simulation of human thinking with the help of

computer programs using list-processing languages and tree structures (H.A.

Simon and A. Newell), and extensions of Hull’s notion of the “habit-family

hierarchy” (I. Maltzman, D.E. Berlyne).

A further development of consequence is a growing recognition that the

essential components of the thought process, the events that keep it moving in

fruitful directions, are not words, images, or other symbols representing

stimulus situations; rather, they are the operations that cause each of these

representations to be succeeded by the next, in conformity with restrictions

imposed by the problem or aim of the moment.

In other words, directed thinking can reach a solution only by going

through a properly ordered succession of “legitimate steps”. These steps might be representations of

realizable physicochemical changes, modifications of logical or mathematical

formulas that are permitted by rules of inference, or legal moves in a game

of chess. This conception of the train

of thinking as a sequence of rigorously controlled transformations is

buttressed by the theoretical arguments of Sechenov and of Piaget, the

results of the Würzburg experiments, and the lessons of computer

simulation. Early in the 20th century both E. Claparède

and John Dewey

suggested that directed thinking proceeds by “implicit trial-and-error”. That is to say, it resembles the process

whereby laboratory animals confronted with a novel problem situation try out

one response after another until they sooner or later hit upon a response

that leads to success. In thinking,

however, the trials were said to take the form of internal responses

(imagined or conceptualized courses of action, directions of symbolic

search); once attained, a train of thinking that constitutes a solution

frequently can be recognized as such without the necessity of implementation

through action, followed by sampling of external consequences. This kind of

theory, popular among behaviourists and

neobehaviourists, was stoutly opposed by the Gestalt school whose insight

theory emphasized the discovery of a solution as a whole and in a flash. The divergence between these theories appears, however, to represent a

false dichotomy. The protocols of Köhler's

chimpanzee experiments and of the rather similar experiments performed later

under Pavlov’s auspices show that insight typically is preceded by a period

of groping and of misguided attempts at solution that soon are abandoned. On the other hand, even the trial-and-error

behaviour of an animal in a simple selective-learning

situation does not consist of a completely blind and

random sampling of the behaviour of which the learner is capable. Rather, it consists of responses that very

well might have succeeded if the circumstances had been slightly

different. A. Newell, J.C. Shaw, and H.A. Simon pointed out the indispensability

in creative human thinking, as in its computer simulations, of what they call

“heuristics”. A large number of possibilities may have to

be examined, but the search is organized heuristically in such a way that the

directions most likely to lead to success are explored first. Means of ensuring that a solution will

occur within a reasonable time, certainly much faster than by random hunting,

include adoption of successive subgoals and working backward from the final

goal (the formula to be proved, the state of affairs to be brought about). Click

here for a list of other articles that contain information on this subject

Contents of

this article: |

The mind is thought to be the seat of perception,

self-consciousness, thinking, believing, remembering, hoping, desiring,

willing, judging, analyzing, evaluating, reasoning, etc.

Dualists

consider the mind to be an immaterial substance, capable of existence as a

conscious, perceiving entity independent of any physical body. Dualism is popular with those who believe in

life after death. The brain may decay,

disintegrate, and be forever annihilated, but the mind (or soul) does not depend on the body

for its existence and so may continue to flourish in another world. This belief in the mind as a substance which

exists independently of the brain, however implausible, seems to be required

for most religious doctrines, as well as for many New Age notions and

therapies. Whereas dualist philosophers

have long struggled with what is known as the mind-body

problem, New Age gurus are calling for mind-body harmony in medicine, therapy

and science. In short, philosophers have realized that

there is a problem in explaining how two fundamentally different kinds of

reality can affect one another, while New Age pundits think the problem has

been caused by treating the two - mind and body - as if they do not

interact.

Metaphysical

materialists, on the other hand, consider the mind to be either the brain

itself or an emergent reality, i.e., an entity separate from but

brought into being by the workings of the brain. The latter doctrine is known as epiphenomenalism. For the materialist ‘mind’ is a catch-all

term for a number of processes or activities which can be reduced to cerebral,

neurological and physiological processes.

Behaviorists consider

‘mind’ to be a catch-all term for a set of behaviors.

There is probably no more fascinating topic in philosophy or neurology

than mind or consciousness.

Yet, despite the fact that the human mind has made it possible to gain

all the understanding of the world and ourselves which we now possess, it has

done precious little to help us understand the mind itself. For example, memory is something we all have

to some degree or another. Yet, we do

not fully understand the nature of memory, and several models of memory are

equally plausible.

Models of mind or consciousness continue to occupy the

brains of some of our best philosophers and scientists. Yet, despite the fact that the key to

understanding the human mind is likely to be found in the study of the

functioning human brain, many philosophers

and psychologists continue to be

guided by the belief that the mind can be adequately understood independently

of the brain.

Philosophers, who have not yet adequately explained

what the mind is, are nevertheless clear enough on the concept to believe there

is a problem in proving

that other minds exist. Presumably they use their own minds to either prove

than other minds exist, or that other minds don’t exist, or that other minds

might exist but we’ll never know for sure.

This might be called the mind leading the mind problem.

See related entries on astral projection, dualism, free will, materialism, memory , souls, Charles Tart, and p-zombies.

further reading

The Paleo Ring -

Websites on Paleontology, Paleoanthropology, Prehistoric Archaeology, Evolution

of Behavior, and Evolutionary Biology

Mind and Body: René

Descartes to William James by Robert Wozniak of

"Deciphering

the Miracles of the Mind ," by Robert Lee Hotz.

Churchland, Patricia Smith. Neurophilosophy

- Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press, 1986).

Damasio, Antonio R. Descartes'

Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (Avon Books, 1995). $10.80

Dennett, Daniel Clement. Brainstorms:

Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (Montgomery, Vt.:

Bradford Books, 1978).

Dennett, Daniel Clement.

Consciousness explained illustrated by Paul Weiner (Boston : Little,

Brown and Co., 1991).

Dennett, Daniel Clement.

Dennett, Daniel Clement. Kinds

of minds: toward an understanding of consciousness (New York, N.Y. :

Basic Books, 1996). $8.80

Dennett, Daniel Clement. Elbow

room: the varieties of free will worth wanting (Cambridge, Mass. : MIT

Press, 1984). $14.95

Hofstadter, Douglas R. and Daniel C. Dennett The mind's I: fantasies and reflections on self and soul (New

York : Basic Books, 1981). $14.36

Hofstadter, Douglas. Metamagical

Themas: Questing for the Essence of Mind and Pattern (New York: Basic

Books, 1985). See especially chapter 5, "World Views in Collision: The

Skeptical Inquirer versus the National Enquirer". $18.40

Ryle, Gilbert. The Concept of Mind

(New York: Barnes and Noble: 1949). $12.95

Sacks, Oliver W. An

anthropologist on Mars : seven paradoxical tales (New York : Knopf,

1995). $10.40

Sacks, Oliver W. The man who

mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales (New York : Summit

Books, 1985). $10.40

Sacks, Oliver W. A leg to stand

on (New York : Summit Books, 1984). $10.00

Sacks, Oliver W. Seeing voices

: a journey into the world of the deaf (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1989). $8.80

The Benefits of Playing Chess

Although Chess is recognized as the ultimate game, somehow, it has fallen from its once exalted position to a place a little lower than that dice game called Yahotze, or whatever it’s called.

What most

people don’t understand is that Chess is not simply a game. It is a learning tool for the development of

the mind, and just happens to be in the form of a game. How fortunate we are to

have an easy method of exercising and developing much deeper thought processes

in our minds while also amusing the simpler side of our nature.

It is also an

unending challenge. Its spectrum extends

from “learning how the pieces move,” to seeing how many simultaneous blindfolded

games we can play. Obviously it takes a

highly developed mind just to play one game blindfolded. And for most of us, playing Chess is much

more fun than using math for this necessary mental exercise.

That’s why

thinking games are such excellent tools for young children. They can be played and enjoyed while deeper

thought patterns are being developed.

Suggestions,

Feedback, or Comments