Jack Bell

John (‘Jack’) Bell was the eldest son and was born at home in Mabbot Street on the 4th Feb 1896.

He was eighteen and a half when war broke out and so was eligible for military service right from the start. We have no precise details of when and why he enlisted. However, we have a letter he wrote home from his camp in Scotland to his family in March 1917 in which he has just celebrated St. Patrick’s Day.[i] As training lasted several months, it is most likely is that he joined the war-time army in early 1917. However Jack’s army career may, like his father, have begun before war broke out.

The Curragh Camp: Pre-war Enlistment?

Jack’s unit history is more complex than his fathers. We have a picture card of Jack sent from the Curragh Camp, Co. Kildare. The card is signed ‘From your loving son Jack’ on the front and on the back with ‘To Mother with best love from your loving son Jack’. In the picture he is wearing an elaborate cavalry uniform with ‘Harp & Crown’ tunic badges. This would be the dress uniform worn in peace time or formal occasions (as opposed to simple khaki service uniform). These details put him in one of the several Irish cavalry regiments. But which one? Using the 1911 Army dress regulations, we find that the only regiment that matches the style of uniform in the picture and who wore the ‘Harp & Crown’ badge on their dress uniform are the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers.[ii]

There is one further

piece of evidence on the picture card. On the back is written the number 13.3.20.

Read form right to left, this could be the date 20th March 1913. Had

Jack enlisted before the war?

None of the official

military or commemorative records mention Jack’s enlistment in the 5th

Lancers. Furthermore, Soldier’s Died in the Great War gives his place of

war-time enlistment as Glasgow. This means that Jack had either been discharged

or deserted from the 5th Lancers before he joined. British pre-war

discharge papers have survived intact, but there is no record of a John Bell

5th Lancers among them, though it is possible that his pre-war papers were

added to his wartime service record and destroyed along with it.

Was he transferred

from the 5th Lancers to the Royal Scots? There is no official record

of this and it would not account for the record of his enlisting in Glasgow.

Plus, if he was in the 5th Lancers at the start of the war,

it is remarkable that he did not see action until 1917. Had he deserted, but under constant pressure from Crown agents, caught

a steamer and re-enlisted in Glasgow, a place where he would not be known? This

was my assumption until been told firmly that it was not Jack who had deserted.

Perhaps he was found out as been underage (in March 1913 he would have been

only seventeen) and was forced out of the army.

Whatever influenced

Jack to enlist seems to have had a renewed influence after 1914. He was not caught up in the initial wave of

popular volunteering that swept Europe (including Ireland) in 1914. He was not

dissuaded by the political and emotional impact of the 1916 Rising at home, nor

by the hideous nature of the war itself, something that was clearly illustrated

by his crippled father. Teasing through his surviving letter home, the

reference to a rift with his father may mean that tensions at home sent him

overseas, though it may have been the other way round and his very decision to

(re)enlist that created the rift with his father.

Scotland: War-time Enlistment and Training

The official record

of British Army war-dead, Soldiers

Died in the Great War, gives Jack Bell’s wartime place of enlistment as

Glasgow. We lack any family stories about his going to Scotland or reasons for

enlisting, but can only presume that this is true and that Jack took a boat to

Scotland and joined up there.[iii]

Jack’s letter of

March 1917 gives his details as “Pte J. Bell 6[?] coy 3rd RS, No.

38948, Hut B17 Glencorse”. He was a private, service number 38948, in the 3rd

Battalion Royal Scots.[iv]

Like his father’s unit, the 3rd Royal Scots was a Reserve battalion,

used to train new recruits, who were then sent off in batches to other

battalions of the regiment fighting overseas. At this time the unit was based

at Glencorse, Edinburgh.

Training of new

recruits consisted of various activities, such as drilling, marching, fitness,

bayonet and rifle training, and battle tactics, punctuated with chores,

rest-days, camp entertainment and occasional leave. After a few months

training, Jack was drafted off to the front-line. He wrote a postcard to his

family from Folkstone, Co. Kent, dated May 23rd 1917, saying he was

on his way to France. It was only a short distance from Folkestone across the

English Channel to the frontline in France.

France: Arrival at the Front-Line

Once in France, Jack

was assigned to the 11th Battalion Royal Scots.[v]

Looking at their war diary, at this time they were stationed at various places

around Arras, in the Pas-de-Calais region of northeast France.[vi]

This unit was seriously under-strength (only 250-strong on the 7th

June). A succession of drafts brought it up to 700 by early July. However, very

soon after Jack arrived in France, a number of men attached to the 11th

Royal Scots, including Jack, were drafted off to the 10th

Cameronians. At what point it happened we cannot tell, as Jack’s army service

record is missing and the battalion war-diaries make no reference to the transfer.

It could have happened anytime up to the 25th July 1917 as this is

when the 10th Cameronians received their last draft of men before

the offensive in which Jack died.

On been assigned to

the 10th Cameronians (also called the Scottish Rifles) Jack was

issued a new regimental service number, 41614.[vii]

This unit was stationed further north, across the Belgian border, around Ypres.

This unit was also under-strength, but more importantly, it was part of a

division that would be participating in a major forthcoming offensive (in which

the 11th Royal Scot was not participating), hence the need for it to

receive immediate reinforcements from other units, instead of awaiting men from

its reserve battalions at home.

Both the 11th Royals Scots and 10th

Cameronians were in the frontline during the months of June and July and

undertook raids on the enemy trenches. However, we cannot know for certain if Jack saw combat or was under-fire before

the battle in which he died.

Belgium: The Third Battle of Ypres

With more certainty

we can trace the events of his last days. For this we have Commonwealth War

Graves Commission records, the private history of the 10th

Cameronians, and the personal testimony of an army friend of Jacks, who visited

his family to tell them of his last hours.

We do not know

anything about this friend who bore the story of Jack’s death. He may have been

Irish, or else he made a long journey to bear his news. That Jack had a friend

willing to undertake this role shows they knew each other a while. Perhaps he

had been drafted to the Cameronians from the Royal Scots along with Jack.

“I remember my father telling me that his mother (Hannah Bell) told of an army friend coming to the house and explaining what happened. The story goes that the regiment were fighting over the same piece of ground with the Germans driving them back and John's regiment recapturing the ground again. Apparently on the third such occasion they went over the top and a large shell exploded amongst them. When the dust cleared John was nowhere to be found.” [viii]

His friends account

fits well with the post-war history of the battalion written by surviving

officers. Jack’s unit were part of the British forces assembled to take part in

a major offensive to capture territory to the east of Ypres. The offensive

began on 31st July 1917 and is called the Third Battle of Ypres. It

was one of most infamous battles of the war, involving huge casualties on both

sides, with little actual change to the ground held. A full account is available of the

opening battle from the 10th Cameronians perspective. It details the hour by hour fortunes of the

battalion right down to company level. In summary, the portion of the

battlefront that they were involved in saw an initial advance on the 31st

July, but then strong enemy counter-attacks. There were heavy artillery

barrages by both sides and intense fighting amid the surrounding farms, fields

and trenches. The battalion took heavy casualties and were eventually forced to

retire as they were in danger of been completely overrun by the enemy to their

front and sides. The 10th Cameronians were withdrawn from the battle

on the night of August 1st.[ix]

In less than 48 hours, Jack’s company

had been reduced from some100 men to only12 men. The rest were dead, captured,

or wounded. Jack was among those missing. At some point amid the carnage, he

had been killed by artillery fire.

His family received

a telegram (dreaded in homes throughout Europe) informing them Jack was missing

in action. In time the army confirmed his status as killed in action (up to

this point there was the possibility a missing person had been captured, news

of which would take time to be relayed). Sadly Jack Bell’s body was never

identified.

Commemoration at Home and Abroad

Jack’s memory was

held dear by his brothers and sisters. His sister Hannah wore a locket with his

picture in it. Pictures of him and Christy were copied and handed down, as well

surviving personal documents and various stories. They also treasured the medals and a memorial plaque issued to them, as

next-of-kin, by the British authorities.

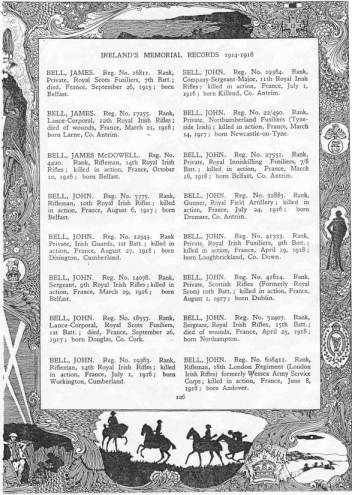

On an official

level, as a casualty of the Great War, Jack Bell was commemorated by inclusion

on war memorials and on various lists of the dead. For instance, he is listed

in the UK’s Soldiers Died in the Great War, and the elaborately

illustrated Irish version, Ireland’s Memorial Records 1914-1918.

Ireland’s Memorial Records

1914-1918

(Jack’s entry is the third last on the page)

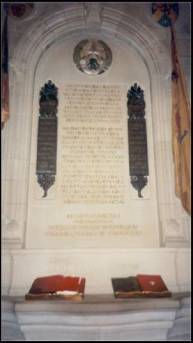

The Scottish

National War Memorial in Edinburgh Castle contains a memorial for each individual

Scottish regiment. Below each memorial is a book of those who died in that

regiment. Jack is recorded in the Cameronian book as “Bell, J 41614 Pte. France.

1/8/17. 10th Bn.”.[x]

The Scottish National War Memorial

His name is also

recorded on the Menin Gate memorial in the town of Ypres, Belgium, close to

where he died. The Menin Gate commemorates British Army soldiers with no known

grave.[xi]

This large arch stands across the western entrance to the town. On it are

inscribed the names of over 50,000 soldiers from across the world. John Bell is

commemorated on Panel 22. Each evening at 8 o’clock, the local fire brigade

gather here and play the ‘Last Post’ in memory of those who fell.

Menin Gate Memorial,

Panel 22

![]()

Personal Documents Third Battle of Ypres Menin Gate

War Years John Bell Christopher Bell War Medals War Map

![]()