The evolution of the flying boat proceeded rapidly in the 1920s and 1930s. Development of the type reached a peak during World War II, when large flying boats were fielded by most of the major combatants in substantial numbers.

One of the most prominent of these aircraft was the British "Short Sunderland", an excellent design that made a major contribution to Allied victory, particularly in the Battle of the Atlantic against German submarines or "U-boats". This document provides a history of the Sunderland.

In the early 1930s, competition in development of long-range flying boats for intercontinental passenger service was becoming increasingly intense. Great Britain had nothing to match the new American Sikorsky flying boats that were making headlines all over the world, and the powers-that-be in Britain felt something should be done.

In 1934, the British postmaster general declared that all first-class Royal Mail sent overseas was to travel by air, effectively establishing a subsidy for the development of intercontinental air transportation. In response, British Imperial Airways announced a competition for 28 flying boats, each weighing 16.4 tonnes (18 tons) and having a range of 1,130 kilometers (700 miles) with a capacity of 24 passengers.

The contract went almost directly to Short Brothers of Rochester in England. Short had long experience in building flying boats for the military and for Imperial Airways. However, none of these flying boats were in the class of size and sophistication requested by Imperial Airways. The business opportunity was too great to pass up despite the risk, and so Oswald Short, head of the company, began a crash programme to come up with a design for a flying boat far beyond anything they had ever built.

The head of the design team was Arthur Gouge, later Sir Arthur Gouge. The design he produced, the Short "S.23", was a clean and elegant aircraft, with a wingspan of 35 meters (114 feet), a length of 27 meters (88 feet), an empty weight of 10.9 tonnes (24,000 pounds), and a loaded weight of 18.4 tonnes (40,500 pounds).

The S.23 was powered by four Bristol Pegasus engines, each providing 686 kW (920 HP). Cruise speed was 265 KPH (165 MPH), and maximum speed was 320 KPH (200 MPH). The S.23 featured a new hull design and a new flap scheme to reduce landing speed and run. The big flying boat had two decks: an upper deck for the flight crew and mail, and a lower deck with luxury passenger accommodations.

The first S.23, named "CANOPUS", flew on the 4th of July, 1936. The S.23s were the first of a series of Shorts flying boats for commercial service, collectively known as the "Empire" boats. A total of 41 S.23s were built, all with names beginning with the letter "C", and so they were referred to as the "C-class" boats.

While the S.23 was a great step forward for Short Brothers, it was still not quite the equal of the big Sikorsky and Boeing Clippers that were opening up worldwide commercial routes. The S.23 was relatively overweight and restricted in range and payload. Nonetheless, it performed reliable service in connecting Great Britain with the distant regions of the British Empire: South Africa, India, Singapore, Australia.

The limited range of the C-class boats meant that they could not operate on the high-profile transatlantic route, which was an embarrassment. In 1937, the second and third C-class boats, the CALEDONIA and CAMBRIA, were stripped down and given additional fuel tanks to make the transatlantic run, though their payload was minimal.

The British were so desperate to stay in the race for transatlantic commercial flight that they then came up with an extraordinary scheme, in which a beefed-up variant of the S.23 carried a smaller four-engine floatplane, the "S.20". A single example, with the carrier aircraft named MAIA and the piggyback S.20 named MERCURY, with flight tests in 1937 leading to a mid-air launch of MERCURY in 1938.

The MAIA-MERCURY scheme amounted to little more than a stopgap and a publicity stunt while Short Brothers worked on a better solution. In 1938, they delivered the first of an improved C-class boat, the "S.30", with Pegasus 22 engines providing 753 kw (1,010 HP) each.

Eight S.30s were built, with four configured for mid-flight refueling from Handley-Page Harrow cargo aircraft. Limited transatlantic operations were conducted in coordination with Harrow tankers operating out of Ireland and Newfoundland, until World War II intervened and put a stop to the flights. Another C-class variant, the "S.33", never got into production.

However, three of the bigger and better "S.26" G-class boats were built, with the first, the GOLDEN HIND, delivered in September 1939. The S.26 boats were powered by four Bristol Hercules engines, each providing 1,030 kW (1,380 HP). The G-class boats had a loaded weight of 34 tonnes (75,000 pounds), a range of more than 4,800 kilometers (3,000 miles), and were intended for transatlantic mail shipment.

During World War II, the Empire boats were pressed into military service. Four S.30s were used for ocean patrol, fitted with twin Boulton-Paul turrets, each with four 7.7 millimeter (0.303 caliber) machine guns and racks for external stores. The three S.26 G-class boats were fitted with three Boulton-Paul quad turrets. Only one of these seven, an S.26, survived military service. It returned to commercial operation until scrapped in 1954.

The Empire boats would be little more than a footnote in aviation history except for the fact that this family of aircraft included a military type, the "S.25" or "Sunderland", which would become one of the most famous flying boats ever built.

While the first S.23 was under development, the British military was taking actions that would result in a purely military version of the big Shorts flying boats. A 1933 British Air Ministry requirement designated "R.2/33" called for a next-generation flying boat for ocean reconnaissance. The new flying boat was to have four engines, but could be either a monoplane or biplane design.

The R.2/33 specification occurred roughly in parallel with the Imperial Airways requirement, and while Shorts worked on the S.23 they also worked on a response to the Air Ministry's need at a lower priority. The military flying boat variant was designated S.25, and the design was submitted to the Air Ministry in 1934. Sanders-Roe also designed a flying boat designated the "A.33" for the R.2/33 competition.

The military ordered prototypes of the S.25 and S.33 for evaluation. The first S.25, now named the "Sunderland Mark I", flew from the River Medway on the 16th of October, 1937.

The prototype had been designed with the expectation that a 37 millimeter cannon would be mounted in the nose, but this weapon was deleted. The armament change meant a shift in center of gravity that led to a modified wing and some other changes. The prototype was also fitted with Bristol Pegasus X engines, each providing 709 kW (950 HP), as the planned Pegasus XXII engines with 753 kW (1,010 HP) each were not available at the time.

The prototype went back to the shop after its initial flights for modifications. It flew again with a new wing and Pegasus XXII engines on the 7th of March, 1938. Official enthusiasm for the type was so great that in March 1936, even before the first flight of the Sunderland prototype, the Air Ministry had ordered 21 production examples of the new flying boat.

Delivery of the SaRo A.33 was delayed and did not fly until October 1938. The aircraft was written off after it suffered a structural failure during high-speed taxi trials, and no other prototypes were ever built.

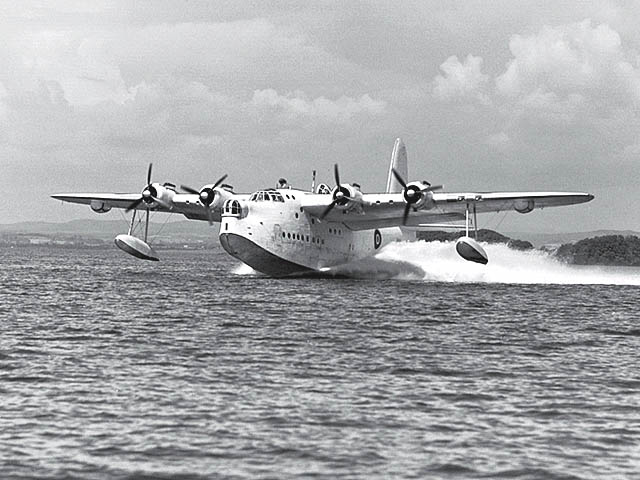

The Sunderland Mark I had much in common with the S.23, but had a different and deeper hull. The installation of nose and tail turrets gave the Sunderland a considerably different appearance from the Empire flying boats.

The FN.11 nose turret mounted a single 7.7 millimeter machine gun, and could be winched back from the nose to allow entrance to and exit from the aircraft through a forward hatch when the flying boat was docked. The new FN.13 tail turret mounted four 7.7 millimeter guns. A single hand-held 7.7 millimeter gun was mounted on either side of the fuselage, above and behind the wing, firing through an oval port with a fairing and sliding door.

The wing, as mentioned, had been modified after the first flight of the S.25 prototype, being swept back 4.25 degrees to compensate for the heavy tail turret, and as a result the Sunderland's engines and wing floats were canted slightly out from the aircraft's centerline. Although the wing loading was much higher than that of any previous RAF flying boat, the new flap system kept the takeoff run to reasonable length.

The thick wings carried the four Pegasus XXII engines and accommodated six drum fuel tanks with a total capacity of 9,200 liters (2,430 US gallons). Four more fuel tanks would later be added behind the rear wing spar to give a total fuel capacity of 11,602 liters (3,037 US gallons). Offensive armament load was 900 kilograms (2,000 pounds) of bombs, mines, or (eventually) depth charges. Ordnance was carried inside the fuselage and winched out under the wings through doors on each side of the fuselage.

The aircraft was of metal construction, except for most of the control surfaces, they had metal frames and were covered by fabric. As with the S.23, the Sunderland's fuselage contained two decks. Of course, the Sunderland was not a luxury liner like the Empire boats, but it had a number of niceties useful for keeping its crew of seven in comfortable during long and exhausting ocean patrols and operations from remote locations, such as six bunks and a galley with a stove. The number of crew would increase in later marques to eleven or more.

Although the Sunderland was not an amphibian, beaching gear allowed it to be pulled up on land. Two-wheeled struts could be attached to either side of the fuselage, while a small two-wheel trolley with a tow bar could be fitted under the rear of the hull.

The RAF received its first Sunderland Mark I in June 1938, when the second production aircraft was flown to Singapore. By the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, the RAF Coastal Command was operating 40 Sunderlands.

Although British anti-submarine efforts were disorganised and ineffectual at first, Sunderlands quickly proved useful in the rescue of crews of torpedoed ships. On the 21st of September, 1939, two Sunderlands rescued the entire 34 man crew of the torpedoed merchantman KENSINGTON COURT from the North Sea. As British anti-submarine measures improved, the Sunderland began to show its claws as well. A Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Sunderland performed the type's first unassisted kill of a U-boat on 17 July 1940.

As the British honed their combat skills, the Sunderland Mark I received various improvements to make it more effective. The nose turret was upgraded to two 7.7 millimeter guns instead of one. New propellers and pneumatic rubber wing de-icing boots were fitted as well.

Although the 7.7 millimeter guns lacked range and hitting power and the British would presently understand the need for more formidable weapons, the Sunderland had a fair number of them, and it was a well-built machine that was hard to destroy. On 3rd of April, 1940, a Sunderland operating off Norway was attacked by six German Junkers Ju-88 fighters, and managed to shoot one down, damage another enough to send it off to a forced landing, and drive off the rest. The Germans were supposed to have nicknamed the Sunderland the "Fliegende Stachelsweine (Flying Porcupine)".

Sunderlands also proved themselves in the Mediterranean theater. They performed valiantly in performing evacuations during the German seizure of Crete, and one performed a reconnaissance mission to observe the Italian fleet at anchor in Taranto before the famous Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm's torpedo attack on 11th of November, 1940.

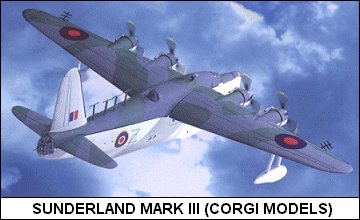

Beginning in October 1941, Sunderlands were fitted with "ASV (Anti-Surface Vessel)" Mark II radar. This was a primitive low-frequency radar system operating at a wavelength of 1.5 meters, featuring a row of four prominent Yagi "stickleback" aerials on top of the rear fuselage, two rows of four smaller aerials on either side of the fuselage beneath the stickleback antennas, and a single receiving aerial mounted under each wing outboard of the float and angled outward. This was an amazing array and was quite unmistakeable. Below is a photo of a 'model' of such a variant of the Sunderland. The 'stickle-back' antenna array is clear to see.

A total of 75 Sunderland Mark Is were built, produced at Shorts factories at Rochester in England and Belfast in Northern Ireland, as well as 15 of the 75 built by Blackburn at Dumbarton.

In August 1941, production moved to the "Sunderland Mark II", which featured Pegasus XVIII engines with two-speed superchargers and provided 794 kW (1,065 HP) each. The tail turret was changed to an FN.4A turret that retained the four 7.7 millimeter guns of its predecessor, but provided twice the ammunition capacity, with a total of 1,000 rounds per gun.

Late production Mark IIs also had a FN.7 dorsal turret, mounted offset to the right just behind the wings, and fitted with twin 7.7 millimeter machine guns, replacing the hand-held guns mounted in the fuselage ports.

Only 43 Mark IIs were built, with 5 of the 43 manufactured by Blackburn. Production quickly went on in December 1941 to the Sunderland Mark III. This variant featured a revised hull configuration, tested on a Mark I the previous June, that provided improved seaworthiness, which had suffered as the weight of the Sunderland increased with new marks and field changes. In earlier Sunderlands, the hull "step" that that allowed a flying boat to "unstick" from the surface of the sea was abrupt, but in the "Sunderland Mark III" it was a smooth curve.

The Mark III would turn out to be the definitive Sunderland variant, with a total of 461 built. Most were built by Short Brothers at Rochester, Belfast, and a new plant at Lake Windemere, but 170 of the total were built by Blackburn. The Sunderland Mark III would prove to be one of the RAF Coastal Command's major weapons against the U-boats, along with the Consolidated PBY Catalina.

| Short 'Sunderland' Mark III | ||

| Specification: | Metric | English |

| Wingspan | 34.4 meters | 112 feet 9 inches |

| Wing Area | 138.14 sq. meters | 1,487 sq. feet |

| Length | 26 meters | 85 feet 3 inches |

| Height | 9.79 meters | 32 feet 2 inches |

| Empty weight | 14,970 kilograms | 33,000 pounds |

| Maximum Loaded Weight | 26,310 kilograms | 58,000 pounds |

| Maximum Speed | 340 Kph | 210 Mph / 180 Kts |

| Service Ceiling | 4,575 meters | 15,000 feet |

| Range | 4,800 kilometers | 3,000 Mi / 2,610 NMi |

New weapons made the flying boats more deadly in combat. The ineffectual anti-submarine bombs, which in some cases were known to bounce up and hit their launch aircraft, were replaced by early 1943 by much more effective Torpex depth charges that would sink to a shallow depth and then explode. This not only eliminated the problem of bounce-back, but the shock wave propagating through the water had greater effect.

Although the bright Leigh searchlight was rarely fitted to Sunderlands, ASV Mark 2 radar allowed the flying boats to effectively target U-boats operating on the surface, until the German submarines began to carry a radar warning system known as "Metox", also known as the Cross of Biscay due to the appearance of its receiving antenna. Kills fell off drastically until ASV Mark III radar was introduced in early 1943. ASV Mark III operated in the centimetric band and used antennas mounted in blisters under the wings outboard of the floats, instead of the cluttered stickleback aerials. Sunderland Mark IIIs fitted with ASV Mark III were designated "Sunderland Mark IIIAs".

Centimetric radar was invisible to Metox and completely baffled the Germans at first. Admiral Doenitz, commander of the German U-boat force, suspected at first that the British were being informed of submarine movements by spies, and there is a story that a Britisher prisoner, a smooth liar, confused them by saying the aircraft were homing in on the Cross of Biscay.

In any case, the Germans responded by fitting U-boats with one or two 37 millimeter and twin quad 20 millimeter flak guns to shoot it out with the attackers. While Sunderlands could suppress flak to an extent by hosing down the U-boat with their nose-turret guns, the U-boats had the edge by far in range and hitting power, although many Sunderlands were field fitted with four fixed 7.7 millimeter machine guns to improve their ability to hit back. One Sunderland that was mortally wounded by U-boat flak is said to have deliberately crashed into the submarine.

Along with the forward-firing guns, Sunderlands were often field-fitted with hand-held 7.7 millimeter and later 12.7 millimeter (0.50 caliber) machine guns on either side of the fuselage.

The rifle-caliber 7.7 millimeter guns were far from entirely satisfactory as they lacked hitting power, but the Sunderland retained its reputation for being able to take care of itself. This reputation was enhanced by a savage air battle between eight Ju-88C long-range fighters and a single RAAF Sunderland Mark III on the 2nd of June, 1943. There were eleven crewmen on board the Sunderland, including nine Australians and two Britishers.

The Sunderland was under the command of Australian Flight Lieutenant Colin Walker. The crew was on an anti-submarine patrol and also searching for remains of an airliner that had left Gibraltar the day before, to be shot down over the Bay of Biscay with the loss of all crew and passengers, including British film star Leslie Howard, known for his starring role in THE SCARLET PIMPERNEL and supporting work in GONE WITH THE WIND.

In the late afternoon, one of the crew spotted the eight Ju-88s. Bombs and depth charges were dumped while Walker 'red-lined' the engines. Two Ju-88s made passes at the flying boat, one from each side, scoring hits while the Sunderland went through wild "corkscrew" evasive maneuvers. The fighters managed to knock out one engine.

On the third pass of the fighters, the top-turret gunner managed to shoot one down. Another Ju-88 disabled the tail turret, but the next fighter that made a pass was bracketed by the top and nose turrets and shot down as well.

Still another fighter attacked, smashing the Sunderland's radio gear, wounding most of the crew in varying degrees and mortally wounding one of the side gunners. A Ju-88 tried to attack from the rear, but the tail turret gunner had managed to regain some control over the turret and shot down the German fighter.

The surviving fighters pressed home their attacks, despite the losses. The nose gunner chewed up one of the fighters and set one of its engines on fire. Two more of the attackers were thoroughly shot up, and the other two finally decided they'd had enough and departed. Luftwaffe records indicate these were the only two that made it back to base.

The Sunderland was a wreck. The crew threw everything they could overboard and nursed the aircraft back to the Cornish coast, where Walker managed to land and beach it. The crew waded ashore, carrying their dead comrade, while the surf broke up the Sunderland.

Walker received the Distinguished Service Order, and several of the other crew received medals as well. Walker went on to a ground job, while the rest of the crew were given a new Sunderland. That Sunderland and its crew disappeared without a trace over the Bay of Biscay two months later, after reporting by radio that they were under attack by six Ju-88s.

Eventually, Sunderlands would claim the destruction of a total of 28 U-boats, and assist in the sinking of seven more. Along with the Atlantic missions, Sunderlands were also used to patrol the Indian Ocean, and were used in Burma to resupply British "Chindit" commando camps behind Japanese lines.

Although a "Sunderland Mark IV" was developed, it proved to be different enough from the Sunderland line to be given a different name, and did not see combat in any case. It is discussed in the following section.

The next actual production version was the "Sunderland Mark V", which evolved out of crew concerns over the lack of power of the Pegasus engines. The weight creep that afflicted the Sunderland resulted in running the Pegasus engines on combat power as a normal procedure, and the overburdened engines had to be replaced on a regular basis.

Australian Sunderland crews suggested that the Pegasus engines be replaced by Pratt & Whitney R-1830-9OB Twin Wasp engines. The 14-cylinder Twin Wasps provided 895 kw (1,200 HP) each and were in use on RAF Catalinas and Dakotas, making logistics and maintenance straightforward. Two Mark IIIs were taken off the production lines in early 1944 and fitted with the American engines.

Trials were conducted in early 1944, and the conversion proved all that was expected. The new engines provided greater performance with no real penalty in range. In particular, a Twin Wasp Sunderland could stay airborne if two engines were knocked out on the same wing, while a standard Mark III would steadily lose altitude.

Production was converted to the Twin Wasp Sunderland, which was designated the Sunderland Mark V, and the first Mark V reached operational units in February 1945. Defensive armament fits were similar to those of the Mark III, but the Mark V was equipped with new centimetric ASV Mark VIC radar, which had been used on some of the last production Mark IIIs as well.

155 Sunderland Mark Vs were built, and another 33 Mark IIIs were converted to Mark V specification. With the end of the war, large contracts for the Sunderland were cancelled, and the last of these great flying boats was delivered in June 1946, with total production of 749 aircraft.

At the time, a number of new Sunderlands built at Belfast were simply taken out to sea and scuttled, as there was nothing else to do with them. However, despite this indignity, there was plenty of life left in the Sunderland.

The Sunderland evolved from a family of commercial flying boats, and would find itself used in that capacity as well. In late 1942, British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) obtained six Sunderland Mark IIIs and stripped them down as mail carriers, with primitive accommodations for seven passengers. They were used for mail service to Nigeria and India.

BOAC obtained more Mark IIIs and gradually came up with better accommodations for 24 passengers, including sleeping berths for 16. These conversions were given the name "Hythe", and BOAC would have 29 Hythes by the end of the war.

Another civilian conversion of the Sunderland was the postwar "Sandringham". The "Sandringham Mark I" used Pegasus engines while the "Sandringham Mark II" used Twin Wasp engines. Apparently most or all of the Sandringhams were modified from existing Sunderlands, but details of the Sandringham are unclear.

The Sunderland Mark IV, mentioned in the previous section, was an outgrowth of a 1942 Air Ministry specification, "R.8/42", for a generally improved Sunderland with more powerful Hercules engines, better defensive armament, and other enhancements. The new Sunderland was intended for service in the Pacific.

Relative to the Mark III, the Mark IV had a stronger wing, bigger tailplanes, and a longer fuselage with some changes in form. The armament was greatly improved, consisting of two fixed forward-firing 12.7 millimeter guns in the nose, a Brockhouse nose turret with twin 12.7 millimeter machine guns, twin 20 millimeter Hispano cannon mounted in a B-17 dorsal turret, twin 12.7 millimeter guns in a Martin tail turret, and a 12.7 millimeter machine gun in a hand-held position on each side of the fuselage,

The changes were so substantial that the new aircraft was redesignated the "S.45 Seaford". Two prototypes and thirty production examples were ordered, and the first prototype flew in April 1945, well after the introduction of the Sunderland IV and too late to see combat.

The prototypes were powered by Hercules XVII engines with 1,253 kW (1,680 HP), but production aircraft used Hercules XIXs with 1,283 kW (1,720 HP). Only eight production Seafords were completed and never got beyond operational trials with the RAF.

The second production Seaford was loaned to BOAC in 1946 for evaluation as a civil airliner. BOAC liked the aircraft, and so 12 Seafords then being laid down were completed as "Solent Mark 2". Most of the RAF Seafords were rebuilt as "Solent Mark 3s".

The Sunderland served on after World War II. During the Berlin Airlift in 1948, Sunderlands shipped food into the British Sector of the besieged city, landing on Lake Havel. They also engaged in maritime patrols over the Yellow Sea in the Korean War, and somewhat oddly served in a counter-insurgency role during the British war against Malayan guerrillas.

Sunderlands helped supply a British Greenland expedition from 1951 through 1954. In 1954, the RAF began to phase out its last Sunderland squadrons, with the type fading out of service through the rest of the decade.

However, 19 Sunderlands had been reconditioned in Belfast in 1951 for the French naval air arm, the Aeronavale, and 16 more were reconditioned in England for the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). The Aeronavale Sunderlands operated until 1960, and the RNZAF Sunderlands served until the mid-1960s, when they were replaced by the Lockheed P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft. A number of Sunderlands were operated by the South African Air Force until 1958, when they were replaced by Avro Shackletons.

Several Sunderlands survive on static display, and at least one Sandringham, owned by well-known warbird collector Kermit Weeks, is still flying. Efforts are under way to get more Sunderlands back into the air.

The Sunderland wasn't the last word in Shorts flying boat design. In 1940, the British Air Ministry issued specification "R.14/40", which requested a four-engine flying boat for the long-range maritime reconnaissance role, featuring heavy defensive armament and an offensive warload of 1,815 kilograms (4,000 pounds). Short Brothers, in collaboration with Saunders-Roe, submitted a design that was accepted, with a contract awarded for two prototypes of the "Shetland", as it was named. Initial flight of the first prototype Shetland was on 14 December 1944, with the aircraft fitted with dummy nose and tail turrets.

The Shetland's general configuration was along the lines of the Sunderland, but the Shetland was substantially bigger, with twice the maximum takeoff weight, and of more modern design, with a "greenhouse" style cockpit. It was powered by four Bristol Centaurus XI 18-cylinder radials with 1,865 kW (2,500 HP) each, driving four-bladed propellers. Range and performance were superior to that of the Sunderland by a clear margin.

| Short 'Shetland' - Prototype | ||

| Specification: | Metric | English |

| Wingspan | 45.8 meters | 150 feet 4 inches |

| Wing Area | 245 sq_meters | 2,636 sq_feet |

| Length | 33.5 meters | 110 feet |

| Height | 11.8 meters | 38 feet 8 inches |

| Maximum Loaded Weight | 56,690 kilograms | 125,000 pounds |

| Maximum Speed | 423 KPH | 263 MPH / 229 KT |

| Cruise Speed | 266 KPH | 165 MPH / 143 KT |

| Service Ceiling | 5,180 Meters | 17,000 feet |

| Range | 7,100 Kilometers | 4,410 Mi / 3,835 NMi |

Trials showed a number of shortcomings in aircraft handling. There doesn't seem to have been any reason to believe the bugs couldn't have been worked out, but the first prototype caught fire at its moorings on the 28th of January, 1946 and was completely written off.

By this time, in an (as it would turn out, very temporary) atmosphere of disarmament and with the era of the large combat flying boat beginning to draw to a close, there was no perceived military need for the type. However, the second prototype was completed, in the form of an airliner with seating for forty passengers, performing its first flight on the 17th of September, 1947. As it turned out, the days of the large flying-boat airliner were also numbered, and the second prototype performed only limited flight trials before it was scrapped.